THE CABIN IN THE WOODS Explained: The Game with the Viewer

However, regardless of the research approach, in times of pluralism and intertextuality, it is difficult to propose a complete and exhaustive definition of the horror genre as such. What proves to be extremely useful, however, is the introduction of the category of progressive cinema that rejects classical forms.

The Cabin in the Woods (2012) by Drew Goddard is yet another proof that horror is turning towards itself, transcending systematicity, and strongly emphasizing the iconography of horror films. The co-creator of Cloverfield plays a game with the viewer—introducing them to a world they know, only to then shatter conventional narrative models.

Postmodernist cinema has a penchant for quoting, paraphrasing, and borrowing. An example is Wes Craven’s Scream, hailed in the 1990s as the precursor of a new wave of Hollywood teen horror films. However, the creators of The Cabin in the Woods take it several steps further.

In the first seconds of the opening credits, symbolic scenes of sacrifices drenched in blood are presented. After the director’s name appears, there is a close-up of a vending machine with the text Enjoy a Fresh Cup of Coffee. The action begins in the modern headquarters of a certain secret organization. A banal conversation between employees follows, interrupted by a freeze-frame and the ominous red title of the film. The action immediately shifts to a small American town, where a group of friends—the stereotypical “fool” Marty (Fran Kranz), the naive “virgin” Dana (Kristen Connolly), the handsome “jock” Curt (Chris Hemsworth), the “blonde” Jules (Anna Hutchison), and the “scholar” Holden (Jesse Williams)—prepare for a weekend trip into the woods.

At this stage, the plot closely resembles Friday the 13th by Sean S. Cunningham, The Evil Dead by Sam Raimi, or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre by Tobe Hooper.

If not for the opening sequence in the lab and the shot of a man with a walkie-talkie on the dormitory roof, one might think they were dealing with a typical slasher. On the way, the youth stops at a run-down gas station. The subjective camera angles (so eagerly used in horror films) in this scene suggest the presence of an observer, intensifying the feeling of danger. Suddenly, a rough-around-the-edges owner appears, strongly reminiscent of Crazy Ralph from Friday the 13th. His character serves as a warning to the protagonists, which, of course, is ignored.

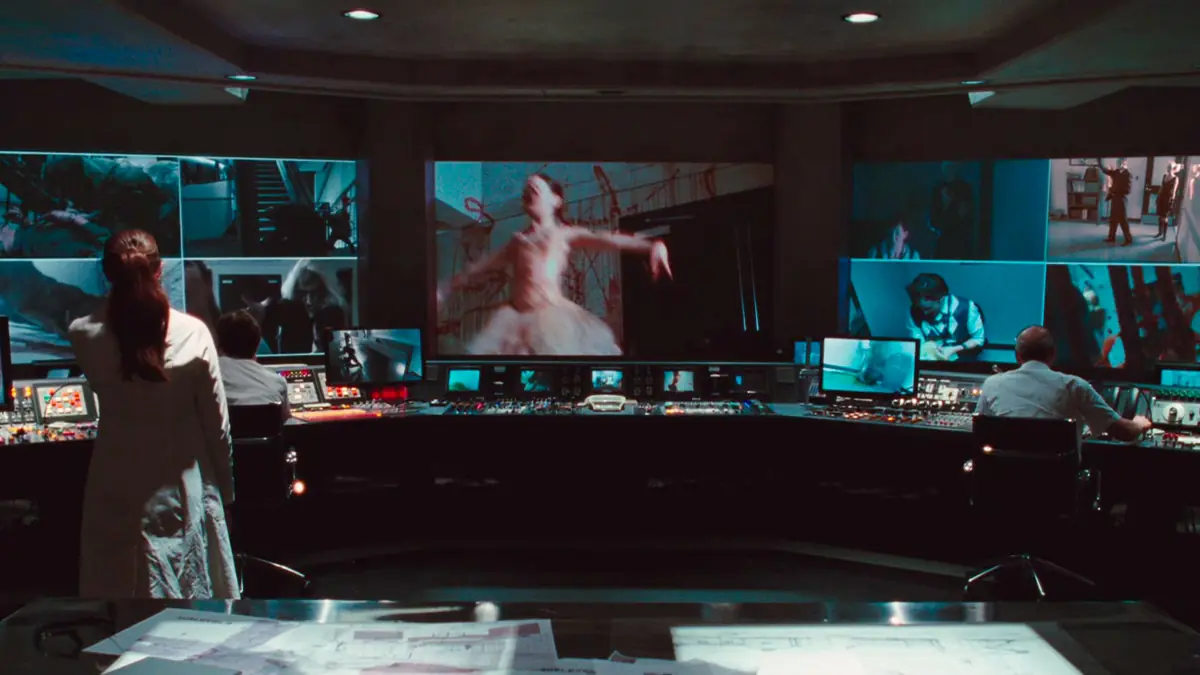

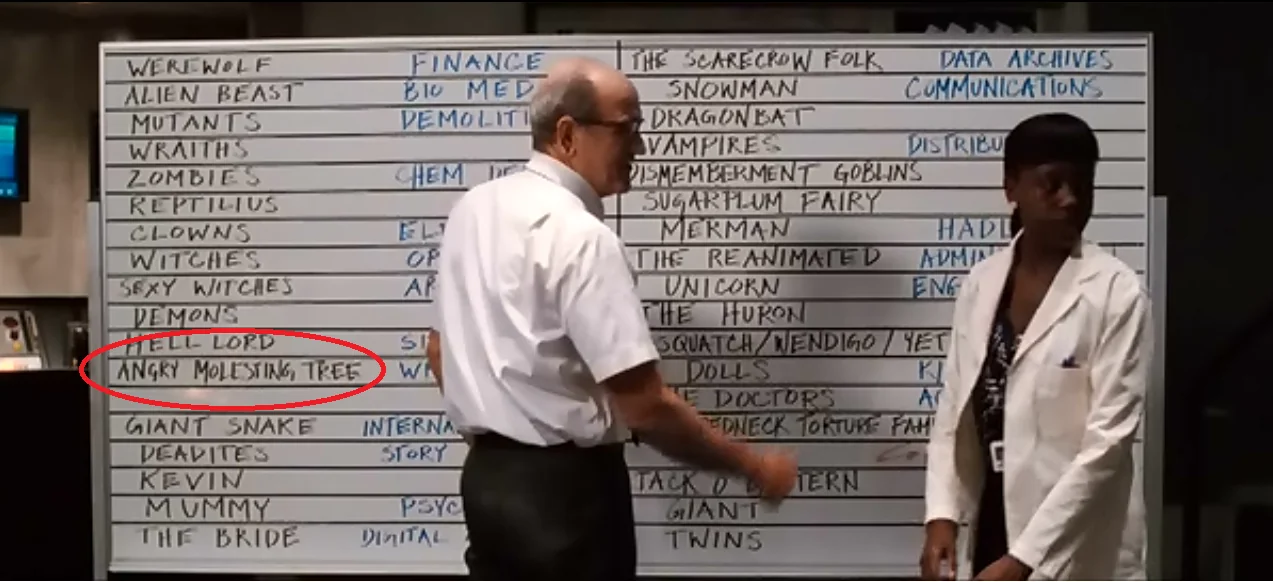

In the next sequence, the protagonists reach their destination. The frog’s perspective shot of the wooden cabin immediately draws a parallel between The Cabin in the Woods and The Evil Dead. However, before the threshold of the cabin is crossed, there is another subjective shot—this time from inside the cabin. Simultaneously, the viewer observes the actions of the protagonists from the perspective of members of the secret organization, who, through cameras and bugs, monitor their every move. Moreover, this organization possesses all the necessary information about the five teenagers. When, in the following sequence, the “scientists” take bets on which monster will be summoned first, the viewer has no doubt—a bloody massacre is inevitable. Only the new employee, with the meaningful name Truman, seems to be the only person questioning the ethics of the project, which aims to sacrifice the group of friends to the Ancient Ones.

Unaware, the protagonists are drugged with chemicals that allow the organization to control their behavior. While the five friends enjoy the pleasures of a summer weekend by the lake, a team of psychologists, doctors, chemists, and technicians takes care of every detail crucial to the success of the project. Everything must go according to the script. This is not the first such undertaking. The entire team knows exactly what they are doing and even has some fun with it.

In a classic horror story about teenagers spending the weekend in a cabin in the woods, the impatient viewer familiar with the genre’s clichés just waits for the moment they go down to the basement. That’s what happens here—during a game of “truth or dare,” the protagonists go down to the basement. Among old furniture, dusty photos, and ominous toys, Dana reads a spell that causes the first monsters—zombies—to rise from the ground in the forest.

No one is surprised that the blonde dies first.

After the spectacular killing of several protagonists, the organization is euphoric. As in a proper horror movie, only the innocent “virgin” remains alive, battling zombies. Everything seems to be going according to plan. However, the sound of a phone, heralding bad news from “outside,” slightly dampens the joyous mood. It turns out that the seemingly harmless “fool” Marty, who, thanks to his drug use, is immune to the chemicals administered by the “mad scientists,” is still alive, so the plan cannot be completed, and the ritual will not be fulfilled. What’s worse, Marty and Dana end up in an underground elevator system that takes them to the very heart of the nightmarish machinery.

The Problem of Identification

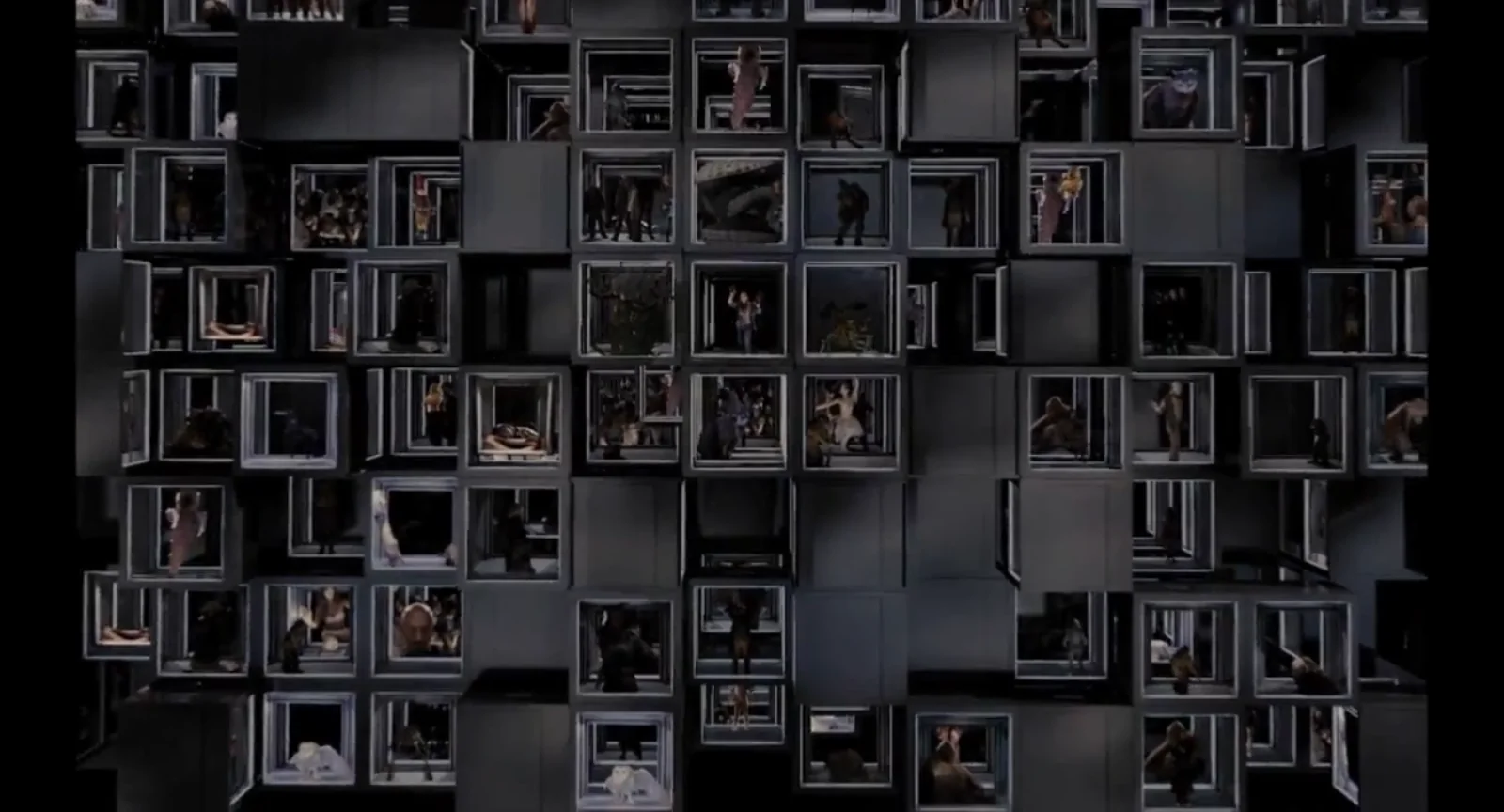

Director and screenwriter Joss Whedon (creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer) skillfully uses well-worn schemes familiar to all horror fans, only to ostentatiously break them. The presented iconography of horror takes on new meaning here. The monsters released from symbolic “cages”: werewolves, mummies, psychopathic murderers, ghosts, zombies, or vampires have an intertextual character, referring to the rich history of horror cinema. But what happens to the viewer of the film?

Goddard serves the audience numerous exaggerations, revealing the workings of the cinematic medium, thus creating a Brechtian effect of alienation.

As A. Pitrus writes, horror can evoke emotions only when it plays with the process of identification. This process, in the case of The Cabin in the Woods, is disrupted. The viewer, who initially identifies with the protagonists, gradually realizes the falsity of this identification as the plot progresses. Its ineffectiveness forces the viewer to experience the film on a <meta> level. The audience distances itself from the film; instead of immersing themselves in the plot, they gradually become aware of themselves as an observer of the cinematic apparatus. Therefore, it is difficult to speak of the “suspension of disbelief” mechanism, which plays a crucial role in the reception of traditional horror films. A similar technique can be observed in G. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. This cult work, which is an ideal model of progressive horror, skillfully “blows up” the conventions of horror cinema from within, using filmic techniques and the art of manipulation.

Horror—Object of Cult or Contempt?

Progressive films are governed by completely different rules than genre cinema. To see how far The Cabin in the Woods departs from Rick Altman’s genre categories, it is worth examining the cataloged characteristics of genre cinema.

Dualism

Classic genre cinema is based on internal dualism—cultural elements are opposed to countercultural ones, good stands in opposition to evil, and the positive hero always triumphs. In The Cabin in the Woods, this principle is broken. The last sequence of the film is particularly telling. Marty and Dana find themselves in a monumental hall where the sacrificial ritual is completed. The carved contours of figures in stone fill with blood every time one of the protagonists dies. Unexpectedly, the person responsible for the bloody massacre appears, played by Sigourney Weaver. Heroic Ellen Ripley, who fought a monster from space in Alien, now plays the Director. However, her death will not save the world. The filmmakers know exactly what the audience expects. They consistently construct the plot “against the grain,” denying the audience a happy ending. In the last, cynical dialogue between Dana and Marty, the protagonists consciously choose to let the “terrifying, great gods” destroy humanity. The inability to defeat evil is a motif characteristic of progressive horror films.

Repetition

Repetition is an essential feature of horror (and cinema in general). Filmmakers’ replication of established patterns guarantees the satisfaction of the average viewer. A horror fan knows exactly what to expect from a survival, slasher, giallo, or traditional ghost story. For Goddard, repetition has a slightly different dimension. The Cabin in the Woods is essentially a collection of intertexts embedded in an unusual (meta) plot. This dual-layered structure, which prevents the viewer’s identification process, reveals the very mechanism of film creation, as well as the director’s intentions. Moreover, the vast number of quotes and references to classic horror films from various periods of cinema encourages a “cult reception.” The filmmakers, by showcasing the analytical possibilities of the film medium, try to encourage the viewer to engage in intellectual effort and critical reflection on pop culture phenomena.

Cumulativeness and Predictability

Intertextuality and the accumulation of many elements specific to a given genre within a single text strengthen its structure. Goddard’s film, much like the cult classic Rocky Horror Picture Show, also cannot exist without “references” to other cultural texts. The viewer clearly recognizes nods to numerous horror films (including The Strangers, Friday the 13th, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Evil Dead, Hellraiser, The Ring, Cube, Saw). Moreover, The Cabin in the Woods combines several genres. Similar to many other films, it features traces of black comedy, science fiction, satire, gore, and even disaster movies. So, what sets Goddard’s film apart from a typical horror? Paradoxically, The Cabin in the Woods does not reinforce the continuity of the genre itself but rather takes on a meta-textual nature—allowing the viewer to engage actively with the film text.

A classic horror is predictable because it is based on established patterns. However, the pleasure of interacting with progressive cinema lies in exposing this predictability.

An example of breaking convention in Goddard’s work is the grotesque ending: in anticipation of imminent death, the resigned characters light a… joint. In the final shot, a giant hand (presumably belonging to an Ancient One) sweeps the cabin off the face of the earth. Just as the filmmakers mischievously suggest in the first scene that we enjoy a “cup of fresh coffee,” the last scene prompts the viewer to draw conclusions and reflect on the film’s intention, which may hide an additional layer of meaning beneath the guise of a joke.

Nostalgia and Symbolism

The nostalgia of genre cinema lies in the constant return to the past, the recreation of myths, and the repetition of cultural tropes. The past always seems better, happier. The Cabin in the Woods also directly refers to the history of horror cinema (and beyond, with examples like The Truman Show). However, in this case, the strong emphasis on iconography goes hand in hand with the creators’ mocking attitude. Nonetheless, the film’s ironic tone does not aim to demythologize the icons and traditions of the genre—on the contrary—it is a form of reverence (the creators themselves admit that they love horror cinema). However, the context and the message of the film should be considered. It seems that the creators’ intent is not to negate the existing legacy of horror but to critique contemporary phenomena such as remake-mania, the lack of creativity among filmmakers (especially those associated with B-movie horror), and the broadly understood moral relativism in art and culture.

Functionality

Genre cinema had to be not only enjoyable but also functional. Classical films often became carriers of values such as family, love, and brotherhood. They were stories with a message. The Cabin in the Woods, as an example of progressive cinema, serves a completely different purpose. Opposing genre cinema, it seeks to challenge values and go beyond systematicity. Playing with convention is, for example, showing viewers the behind-the-scenes preparation of a bloody spectacle by a secret organization (reminiscent of a live-action snuff film). The headquarters of this organization, along with all the technical support where the gruesome events are recorded, will have enormous significance. This deliberate technique by the director once again reveals the cinematic apparatus to the viewer and the immense possibilities of the extraordinary medium that is cinema.

Furthermore, it is surprisingly easy to question the alleged stereotypicality of the five protagonists: the unassuming “fool” is the first to notice the danger, the blonde wouldn’t be blonde if she hadn’t bleached her hair beforehand, and the “virgin” is probably not a virgin. Thus, the filmmakers deliberately stereotyped the characters for the… audience, who, being well-versed in genre templates, are accustomed to superficially recognizing motifs and plot structures.

Both contemporary creators and audiences of horror films are aware of operating within a shared tradition. Goddard’s film plays a special role in the context of contemporary popular culture phenomena. Not only filmmakers juggling ready-made genre clichés are subjected to critical analysis, but also viewers openly manifesting their desire to participate in fictional death spectacles. The issue of the source of violence in cinema was addressed by Michael Haneke in Funny Games. Like Alex from A Clockwork Orange, the viewer is incapacitated by Haneke and condemned to a display of on-screen cruelty. Both Funny Games and The Cabin in the Woods make the audience aware of their fascination with the macabre. Moreover, the deliberate self-reflexivity of Goddard’s work allows for critical insight into the structures of this meta-horror as well as the entire horror genre.

The Cabin in the Woods can be considered not only as an example of progressive cinema that ostentatiously rejects classical forms but also as a pastiche of an intellectual and entertaining nature. The creators themselves admit that their main goal is for the audience to have a great time, “and if someone manages to get something more out of the film—consider it a bonus.”

Written by Martyna Suchoń.