FUNNY GAMES. Michael Haneke’s Shocking Thriller Explained

One of his most internationally renowned works (partly due to his American remake) is the 1997 film Funny Games. Let’s briefly recall the plot of this Austrian director’s creation. Georg and Anna, along with their son (also named Georg), head to their summer home, where they are attacked by two young men, introducing themselves as Paul and Peter, who engage them in a cruel game based on the principle: “You bet you’ll be alive at 9 am tomorrow, and we bet you’ll be dead, okay?”

The Funny Games that Paul and Peter play with the terrified family are not the only games in the film; they are actually far less significant than the game the director plays with the viewer. Throughout the film, Haneke repeatedly poses one simple question: “Why are you watching this?” He is acutely aware of what the audience expects and uses this knowledge to irritate and manipulate them, ultimately attempting to make them reflect on themselves. He achieves this through several techniques.

Haneke in Funny Games is not fighting against the genre framework of a thriller, but rather against the viewer’s expectations. After reading Rafał Syska’s text on thrillers, one can reconstruct the pattern that the audience is familiar with before watching the film and expects to see once again. The structure typically unfolds (in brief and simplified terms) as follows: a calm beginning, fear combined with the suffering of innocent characters with whom the audience sympathizes, a few plot twists – one usually involving a heroic act leading to the punishment of the villains – and everything (or almost everything, as sometimes a good character might die) ends well. In Haneke’s film, nothing of the sort happens. There is no room for a comforting conclusion where the audience thinks: They handled the critical situation well; I’m glad it didn’t happen to me. The film ends with the death of all the victims and one of the killers looking directly into the camera, which I believe can be interpreted in two ways. It can be seen as either a question directed at the viewer: So, are you satisfied with what you watched? or the director’s conviction that despite having watched the film, the audience subconsciously awaits another dose of such emotions, as the last scene clearly indicates that Paul and Peter will continue their killing spree. This method of disrupting the audience’s sense of security (stemming from sitting in a chair and knowing they’re watching a film) was used in the early days of cinema, in Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 film The Great Train Robbery.

Another typical element missing in Funny Games is the backstory of the killers. Usually, such characters come from dysfunctional backgrounds, marked by past traumas (often familial), which allows the audience to understand why they commit such horrible acts. However, Haneke tells us almost nothing about Paul and Peter. In one scene, we learn that the latter is studying medicine, in another, that he is soon going to law school, but first, he will serve in the military. Paul, on the other hand, tells several stories about his companion—once he’s a child from a broken home, another time he’s one of six children in a dysfunctional family where everyone uses drugs or alcohol. It’s easy to guess (and Paul confirms) that these stories are fabricated. The only thing we can assume is that they likely come from a “good” family, as they still try to behave quite politely and know how to do so, although their attempts (like shaking hands and introducing themselves after breaking Georg’s leg) are probably another way to mock their victims and psychologically torture them. The director does not give the viewer a chance to understand the villains’ motivations, mainly because they don’t have any. They kill solely for fun, with no desire for revenge, money, or any “rational” motive. However, while the audience doesn’t understand the killers, they can easily accept their game, resulting in watching the film until the end. Haneke uses Paul and Peter (in a sense, his representatives in interacting with the audience) to show that people want to watch such characters and are fascinated by evil, whose actions are a means to achieve entertainment and an adrenaline rush. (One could draw a parallel between Haneke’s characters and the Joker from Christopher Nolan‘s The Dark Knight, but that’s a topic for another discussion.) Moreover, throughout most of the film, Paul and Peter suggest that everything happening is Georg’s fault for slapping Paul and Anna’s fault for making Peter ask her for a favor earlier. Although this isn’t the real reason they inflict suffering on the family, Haneke seems to suggest that the viewer will accept such a justification because it provides an opportunity for entertainment.

Let’s take a closer look at how the villains of in Funny Games address each other, which further emphasizes their inability to be placed within any specific framework, environment, or context within the film. The two occasionally use cartoon character names. The first instance is Tom and Jerry, the cat and mouse respectively, which in a sense, can be related to the dynamics between the tormentors and their victims. It is a game of cat and mouse, where the stronger side occasionally gives hope to the weaker one without any fear of their plans being disrupted. This is confirmed by the way Peter pronounces “Jerry”—ironically, knowing that his companion is not the mouse being chased by the cat. The second time, the names Beavis and Butt-head are used, referring to the animated series characters who are two adolescent boys whose main activity is watching TV and commenting on what they see. Similarly, Paul and Peter are young men, with Paul occasionally addressing the viewers directly, thereby commenting on what is happening on screen. Both sets of pseudonyms are taken from American productions, which is not accidental, as Haneke portrays American pop culture in Funny Games. It is also noteworthy that the villains’ names (Paul and Peter) refer to two apostles (although this is more of a curiosity than a meaningful clue).

The appearance of the characters of in Funny Games is also important. Their attire is dominated by white (Paul is dressed entirely in white, while Peter wears blue shorts), and they both wear white gloves. This not only makes them look strange and unnatural, standing out against the rest, but white also symbolizes innocence and purity. Haneke seemingly portrays pure evil – without causes or goals, acting solely for entertainment. There is also a suggestion of angels (aided greatly by the poster for the American remake, Funny Games U.S.), but they are angels of death. Even the white gloves can be interpreted in the context of the saying “to do something with white gloves,” meaning to handle something delicately and quietly without drawing attention. The fact that both murderers wear white gloves is likely not due to a concern for leaving traces but suggests that their actions are just a preview of what they are truly capable of. Their true cruelty would be revealed when they take off the gloves.

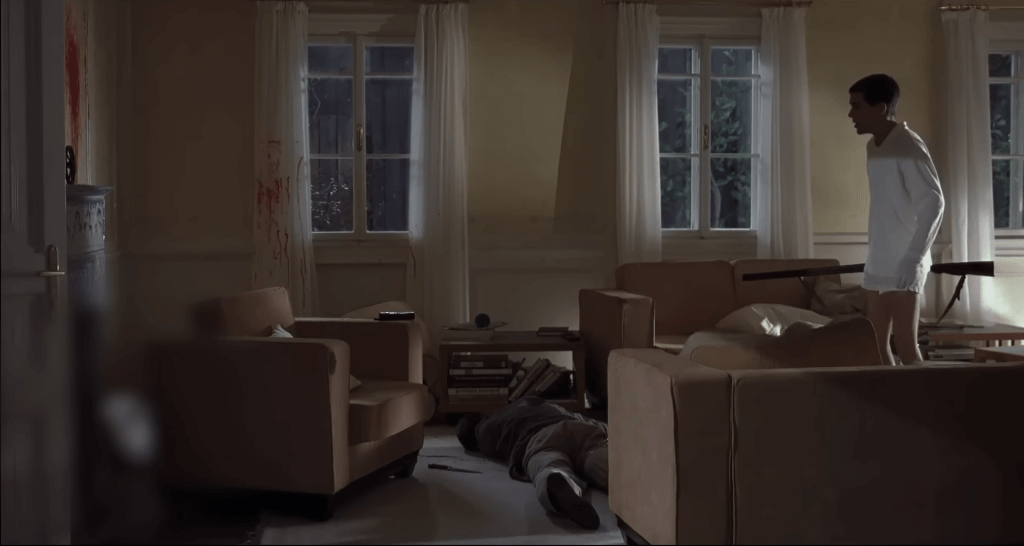

A crucial element of Haneke’s game in with the audience in in Funny Games is the portrayal of the victims. Contrary to what viewers might expect, they are utterly helpless, resigned to their fate, as if they know nothing can save them. They essentially do not fight for their lives, rarely trying to negotiate with their attackers (when they still believe it is possible). Paradoxically, they behave much more realistically than typical characters in such films. In reality, most of us would probably not take more decisive actions either. The actions (or lack thereof) of Georg, Anna, and their son can be explained by shock, fear, and inexperience in such situations. However, it is hard to shake the impression that they are aware of a higher power (the director) present in the film that will not allow them to survive. This prevents the audience from identifying with either the victims or (obviously) the tormentors, causing frustration due to the lack of a point of reference and the fruitless waiting for a plot twist that would bring relief. This is perfectly illustrated in several scenes. One such scene is when Anna, in Paul’s company, talks to friends who have come by boat to invite them to dinner. Although there are three people on the boat who could easily handle Paul, Anna makes no effort to alert them and conducts the conversation calmly, without indicating that anything is wrong. Paul and Peter are fully aware that they control the situation and that nothing can surprise or stop them. A confirming example is when young Georg escapes from the house. Paul follows him without haste, not worried that the boy will alert anyone, and when Georg points a gun at him, Paul calmly advises him to cock the hammer before shooting. The helplessness of the victims and the omnipotence of the tormentors are most evident when, after killing Georg and Anna’s son, Paul and Peter leave the parents alone in the house. Despite freeing themselves, the parents’ behavior does not fit the situation: they do not hurry, inventing bizarre (if not absurd) reasons not to go outside, showing no real survival instinct, determination, or mobilization to change their situation. When they finally separate, it is only a matter of time before Paul and Peter return to the house, capturing Anna along the way.

Haneke anticipates the audience’s reactions. Each time they think they can feel better, that the expected plot twist is coming, the director brutally disrupts their equilibrium. In a way, it is quite perverse, as Haneke uses these tricks until the very end. In the final scene, when Anna, tied up on the boat, finds a knife and tries to free herself, she is quickly overpowered and thrown overboard. The same applies to the relationship between Paul and Peter, where at some point, the audience might hope that a conflict between the murderers will be the source of salvation. But nothing of the sort happens. Haneke’s perfect understanding of audience expectations allows him to manipulate their emotions and reactions, making their hopes collapse like a house of cards. However, Haneke does not limit himself to just that.

A primary artistic device that runs throughout in Funny Games and serves the director in delivering his message more forcefully are the moments when Paul directly addresses the camera. In this way, Haneke seems to tell the audience that he knows exactly what they expect, that he is playing with them, while also reminding them that what they see on screen is just a film. The first moment when the viewer realizes the director is addressing them occurs when Paul, guiding Anna to the dog’s corpse (saying “warm” or “cold”), turns to the camera and winks with a smile. The second time, he asks what the viewer thinks about the bet proposed to the family, suggesting that the audience sympathizes with the innocent victims. The third instance is when Georg says they should just do what they have to do (kill), to which Paul replies that it is cowardice, that they have not yet reached feature film length, and asks the audience: Enough? You want a real ending with a convincing development, right? Haneke essentially spells out what he wants to show the viewer, what he wants to force them to experience. However, many other dialogues can also be interpreted as indirect communication with the audience. This is well illustrated in the scene where Peter, alone with Georg and Anna, who asks why they do not just kill them, says: Let’s not forget the entertainment value. We would all be deprived of the pleasure. Similarly, when Anna pleads with him to let them go, saying it is not too late, Peter tells her to stop, suggesting that the main person deriving pleasure from the whole situation is the viewer.

However, the most crucial moment of in Funny Games when Haneke almost laughs in the viewer’s face, mocking their expectations for a positive turn of events, is the scene where Anna manages to grab a gun and shoot Peter. An annoyed Paul soon finds the remote, rewinds the tape to a moment just before the shot, and when Anna reaches for the gun again, he stops her without much trouble. The director clearly shows that he is in control here, and if the audience doesn’t like it, they could have stopped watching long ago. Haneke seems to be saying that everything happening on screen is a show, with human life at stake, and the viewer sits down to watch someone’s death. Subconsciously (or not), they want it, maybe even need it, because they derive satisfaction from such situations.

Haneke demonstrates several times that television is largely responsible for the state of contemporary pop culture. First, Paul sums up the bet with the family with the words: As they say on TV: the bet stands! Secondly, the moment when Peter, guarding Georg and Anna, watches TV, constantly switching channels because everything becomes instantly boring, reflects the average viewer, who also channel-hops and seeks increasingly extreme ways to kill boredom. The scene where, after shooting young Georg, we see a blood-stained TV screen showing racing cars is also significant. This suggests the insensitivity of today’s television, which quickly moves on from tragic events because there are more images and tragedies to show. As Wisława Szymborska wrote in her poem The End and the Beginning: All the cameras have already left for another war.

Another method Haneke uses to influence the viewer’s emotions is his filming technique. The scene where Paul and Peter leave Georg and Anna in the house with their dead son’s body is distinctly different from how most of the film is shot. The shots are significantly longer (a hallmark of Haneke’s style), almost static at times. This makes the viewer, first of all, potentially bored, expecting some action (subconsciously wanting the killers to return because “something will start happening”), and secondly, irritated by the characters’ behavior as they are in shock, making ineffective attempts to seek help. This disrupts the viewer’s rhythm, almost making them scream, Do something, it’s not too late, stemming from the aforementioned expectations that everything will end well.

In this way, Haneke makes the viewer realize they have just watched almost two hours of material where two young men torment a helpless family and forces them to consider why this happens. Waiting for familiar plot resolutions, the viewer can accept everything they saw. And the director of in Funny Games spares no means. Paul and Peter torment their victims not only physically but also mentally, often humiliating them, like when they force Georg to command Anna to strip under the threat of killing young Georg, just to check if they were right about her figure and body fat. Another cruel act is forcing Anna to say any prayer, with the reward being the chance to choose who (she or her husband) will be killed first and with what object (a shotgun or a knife). This also references TV shows where decisions are made about who gets eliminated. Here, viewers wait to see what choice the tormented woman will make.

Funny Games is often labeled a brutal, violent film. However, a closer analysis reveals something interesting. Haneke shows very little directly. All the most brutal scenes, like killing the dog, breaking a leg with a golf club, or shooting the son, happen off-screen. The director hides these from our eyes, likely to make the viewer feel somewhat disappointed (as in other films, gruesome murder scenes are shown without restraint). When the viewer wonders why they feel disappointed, they might do a sort of self-examination, feeling bad (or at least they should). In this sense, Haneke’s work is brutal—not in the violence on screen but in the violence applied to the viewer and their mind. The creator torments the audience far more than the characters.

A few words about the soundtrack of in Funny Games are also warranted. The only music heard during the film are classical pieces at the beginning, highlighting the apparent tranquility of the carefree family’s trip, and a very fast and harsh track by John Zorn, featuring screams and moans, used three times: as the backdrop to the opening credits, quickly disturbing the peace (even for the viewer), foreshadowing the events to come; when Paul searches for young Georg in the neighbor’s house, likely to heighten viewer tension; and at the film’s end, when the title reappears, emphasizing that Paul and Peter’s actions are far from over.

In Funny Games, Michael Haneke undertakes a perverse game with the viewer to show and make them aware that global pop culture (predominantly American) is dominated by omnipresent violence and brutality, largely due to the audience’s own needs. All this aims to make the viewer reflect on themselves, what they enjoy watching, and what constitutes entertainment for them. Judging by the fact that Haneke made an American remake ten years later (a very faithful copy of the original), it can be inferred that his goal was not achieved, and his message did not resonate.

Words: Jedrzej Dudkiewicz