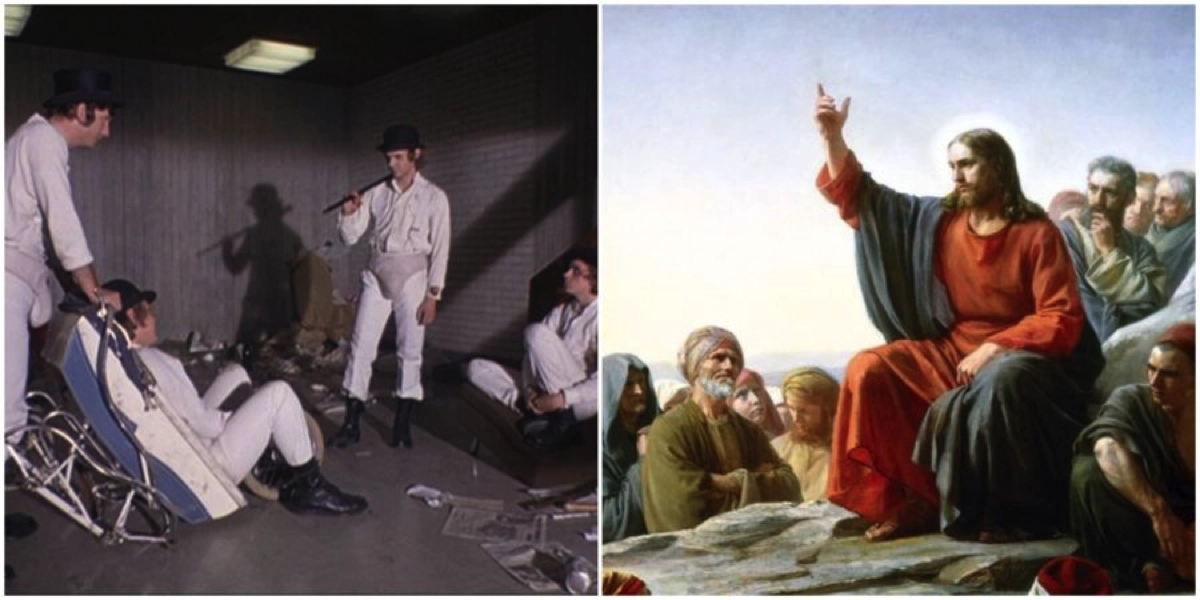

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE explained. Alex Delarge as Jesus Christ

He steals, abuses the homeless, gets into fights with other depraved youths with his friends, and ultimately even commits murder, albeit unintentionally.

As if that were not enough, Alex does not feel the slightest remorse for his reprehensible actions. In fact, his villainous, repugnant deeds clearly bring the protagonist extraordinary pleasure. Therefore, it would seem that there are few film or literary characters further removed from Jesus Christ than Alex DeLarge. But nothing could be further from the truth. A careful viewing of A Clockwork Orange reveals at least a few elements that clearly indicate the similarity of DeLarge’s fate to the last days of the Messiah on earth.

Betrayal and Capture

Alex is a born leader with a great aptitude for leadership. For this reason, it is he, not Pete, Georgie, or Dim, who manages the gang’s activities. He plans the robberies, gives orders, and even takes the wheel of the jointly stolen Durango 95—the “car from hell.” In short, Alex enjoys a great deal of authority among the other members of the group. He sets the rules; he is the alpha and omega of the gang. It is hard not to notice that the relationship between Alex and his colleagues resembles the one in the New Testament between Christ and the apostles. In addition, Alex is also betrayed and handed over to the authorities. In the case of A Clockwork Orange, the biblical role of Judas is fulfilled by no less than three people—DeLarge’s closest friends, members of his gang.

Before Alex is betrayed by his “apostles” and ends up in police custody, it is worth noting one crucial issue. Like Jesus, DeLarge is not interested in material goods. At the moment when the hero relaxes in his room after a successful operation, the camera presents the interior of his drawer to the viewers for a few seconds. It contains various valuables: watches, jewelry, cameras, and finally, high-denomination banknotes. Alex does not sell these items. He treats them as trophies, spoils—they have no material value to him. I would even venture to say that Alex collects them out of simple human sentiment. After all, they are tangible mementos of the incredibly satisfying acts of “ultraviolence.” DeLarge’s lack of interest in worldly goods is also evident in the scene where Pete, Georgie, and Dim pay an unexpected visit to Alex. One of them proposes a robbery of Lady Cat’s house, promising significant financial gains for the group. Surprised, Alex asks, And what would you do with such a big pile of cash? Don’t you have everything already? These words, of course in a slightly different stylistic form, could just as well have been spoken by Jesus Christ and found their way into the pages of the New Testament.

Let’s return to the core of the matter, the continuation of the plot of A Clockwork Orange. Alex, stunned, is found by police officers outside the dying Lady Cat’s house. The next scene takes place at the police station, where DeLarge is brutally interrogated by law enforcement officers. At one point, Mr. P.R. Deltoid, a social worker assigned to Alex’s case, enters the room. The man informs the hero of Lady Cat’s death and then, encouraged by one of the officers, spits directly in the protagonist’s face. This is a significant, highly powerful gesture—absolute humiliation. It is worth noting that the camera lingers on Alex’s spit-covered face for a particularly long time, about 20 seconds! In this way, Kubrick emphasizes the importance of this seemingly trivial event. It has a very important symbolic dimension. In almost identical fashion, Jesus Christ was humiliated by Roman soldiers. In the Gospel according to St. Matthew, we find the following passage:

Then the governor’s soldiers took Jesus with them to the praetorium and gathered the whole cohort around Him. They stripped Him and put a scarlet robe on Him. Weaving a crown of thorns, they placed it on His head, and a reed in His right hand. Then they knelt before Him and mocked Him, saying, ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’ They spat on Him, took the reed, and struck Him on the head. After mocking Him, they took off the robe, put His own clothes on Him, and led Him away to crucify Him.

The true torment of both Alex and Christ, however, was only just beginning.

Tortures

DeLarge adapted quite well to prison. He became the chaplain’s favorite and assistant, devoting himself to “studying a certain Great Book” for show and to pass the time. In a scene where he is reading the Bible, the hero imagines himself as a Roman warrior who helps flog Christ and even drives in the nails himself. Poor Alex does not yet know that he will soon endure torments comparable to those of Jesus.

DeLarge brings the avalanche of suffering upon himself, fully consciously attracting the minister’s attention during a prison visit. As a result, Alex is chosen by the politician as a candidate for the experimental Ludovico therapy. After completing all the formalities, the hero is taken to the research facility and informed by Dr. Branom that the treatment will involve watching films. Later that day, Alex’s “way of the cross” begins in a specially constructed cinema.

The hero is completely immobilized. Due to the straitjacket, he cannot move any of his limbs. His eyes and head are restrained with wires and cables. At this point, one can notice a striking resemblance between the tangle of wires on Alex’s forehead and the crown of thorns Christ wore during his “way of the cross.” In my opinion, this is no accidental coincidence but a fully conscious and deliberate technique by the director.

Without a doubt, Alex suffers terribly during the therapy. He writhes in his chair, screams at the top of his lungs, and tries to avert his gaze from the screen showing extremely brutal acts of “ultraviolence.” Finally, when DeLarge recognizes his beloved Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in the musical background, he begs the doctors for mercy and to stop the screening. He shouts the telling words, “This is a sin!” six times. However, Alex’s fervent protests are in vain—the therapy, like the “way of the cross,” must be completed. The therapy culminates in the presentation of the “cured” DeLarge to the minister and the gathered guests. Like Jesus on Golgotha, Alex, exposed to public view, is forced to endure more insults and ridicule for the crowd’s amusement. They serve as a kind of test, a trial to confirm the Ludovico therapy’s effectiveness. Ultimately, the hero is proven to be cured. Unable to commit evil, he is released. The minister sums up his current state with the words, He is a true Christian, ready to turn the other cheek. He would rather be crucified than crucify!

Passion and Death

The worst awaits Alex after being released. Before the “death on the cross,” which takes the form of a suicide attempt in *A Clockwork Orange*, the protagonist will be humiliated three times. The number three is crucial here—Jesus fell exactly three times under the cross’s weight during his journey to Golgotha.

Alex experiences rejection for the first time at his family home. It turns out that his parents have rented his former room to a lodger, whom they treat like their son. Humiliated, DeLarge discovers there is no longer any place for him in his parents’ home. He has no choice but to wish his dear parents the greatest guilt and then leave with his few belongings as far away from them as possible.

Moments later, Alex is humiliated for the second time. This humiliation is connected to the tramp he abused with his gang in the film’s second scene. The homeless man sees the protagonist staring blankly at a nearby bridge (perhaps a sign of suicidal thoughts forming in the hero’s mind). The tramp approaches, asking Alex for alms. Unfortunately for DeLarge, the homeless man recognizes him as the one responsible for his beating. The hero is soon attacked by a gang of beggars, spurred on by Alex’s former victim. The paupers surround the protagonist, kicking and pulling him from all sides. This scene seems incredibly dynamic, mainly due to the accumulation of rapid editing cuts. With a little imagination, one can see suggestive allusions to the way of the cross. After all, Jesus was also surrounded by a hateful crowd during his journey to Golgotha, and their activity was not limited to hurling insults. In both Christ and Alex’s situations, responding with violence is impossible. Both characters try to endure the suffering imposed on them bravely and silently.

Alex is rescued from his predicament by two police officers who happen to be nearby. However, we quickly realize that the hero has fallen from the frying pan into the fire. The police officers who came to his rescue turn out to be Georgie and Dim—Alex’s former gang buddies. For fun, they drive the protagonist to the woods, where he is humiliated for the third time. DeLarge is dunked, beaten, and finally left for dead by his former companions.

It seems that Alex’s torment comes to an end after he finds himself in the home of the subversive writer Alexander—a man he once tormented along with Pete, Georgie, and Dim. Initially, the man provides the hero with shelter and assistance but soon realizes who he is truly dealing with. Before DeLarge is poisoned, imprisoned, and driven to suicide with the help of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, he has dinner at Alexander’s. It is implied that this is his last supper—therefore, it is worth noting the composition of this meal in this context. In my opinion, the fact that the last drink Alex consumes before attempting to take his own life is red wine—one of the most important symbols of Christianity—is not without significance.

Let’s take a moment to look at the scene of DeLarge’s failed suicide attempt. The soundtrack particularly stands out. Why? Because the viewer quickly realizes that they have heard exactly the same fragment of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in an earlier scene. An almost identical soundtrack (the second time, it is only slightly distorted due to being processed through a synthesizer) accompanied the scene of the “dance” of the four Christs in Alex’s room. This gives us grounds to compare these two fragments of A Clockwork Orange. What results from such a collision? The possibility of interpreting the “dance” scene as a foreshadowing of DeLarge’s future suffering. The quintessence of this suffering is the scene of the suicide attempt.

Resurrection

After the failed suicide attempt, the hero ends up in the hospital. There, he slowly begins to recover—not only physically but also mentally. The effects of the Ludovico therapy disappear, and DeLarge is once again a free man with the ability to choose. The quintessence of Alex’s recovery, his “resurrection,” is the visionary scene that closes Kubrick’s film. In slow motion, the hero has sex with a girl while the audience around them applauds. The location where this act takes place—a dug-up grave—is extremely important. Through the choice of location, the director explicitly signals to the viewers that Alex’s recovery can be interpreted as a kind of resurrection. It is worth noting that in Anthony Burgess’s novel, on which Kubrick’s film is based, the protagonist’s visionary scene takes a completely different form:

Oh, what a wonderful and yum yum yum. When the Scherzo began, I saw myself so clearly, running and running as if on very light and mysterious legs, slashing my razor at the screaming world. And there was still the slow part and the wonderful last singing. I was cured alright.

The director did not follow the book’s original blindly in this case. He creatively betrayed Burgess’s novel—modifying Alex’s visionary scene slightly, thus allowing for a broader interpretation.

Can DeLarge’s character be read as an example of a Christ figure? I think so—it is indeed an extremely unusual case, but the similarities in their fates are significant. God forbid I claim that A Clockwork Orange is really a disguised story about the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ and that Kubrick’s work should not be analyzed or interpreted in any other way. I merely believe that the passion theme is clearly present in this film. And it would be a sin not to notice it.

The analysis was inspired by a lecture by Professor Krzysztof Kozłowski from the Department of Film, Media, and Audiovisual Arts at Adam Mickiewicz University.