REAR WINDOW Explained: The Darkness Within the Human Soul

What are you looking for out there?!

I want to find out what happened to the traveling salesman’s wife.

Does that mean I’m crazy?

Alfred Hitchcock. Two words that electrify generations of cinema lovers like few others. A name synonymous with total cinema, celluloid perfection, and directorial mastery in every frame. A director who always distanced himself from high art while creating it. A master who seamlessly blended clear-cut, thrilling plots with deep metaphorical and philosophical messages. Finally, a genius of cinematic technique whose camera work and editing solutions remain an unrivaled standard to this day. Rear Window

After arriving in the U.S. from his native Great Britain, Alfred Hitchcock created his greatest masterpieces across the Atlantic, peaking in the 1950s and 1960s. Strangers on a Train, Dial M for Murder, Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds—who doesn’t know these titles? Each of these films is a masterfully told crime thriller featuring Hitchcock’s trademarks: suspense and the theme of an ordinary person suddenly facing an incomprehensible threat. According to Hitchcock, the world’s evil lurks everywhere, and it takes just a stroke of fate for the average citizen to feel the illusory stability of daily life unravel.

Looking at the careers of today’s top Hollywood directors, one might conclude that the artistic quality of a film comes directly from grand staging and ever-larger budgets pumped into production and promotion. Recent examples seem to confirm this rule. Cameron, Jackson, Scott, and Spielberg reached new heights of directorial genius because they created outrageously expensive blockbusters (though, personally, I believe Scott will never surpass the much humbler Blade Runner).

Quality often comes with a lack of constraints. Hitchcock, though he didn’t make typical blockbusters, took the opposite approach in some of his films. By limiting budget, crew, and filming locations to a minimum, he demonstrated how to create absolute cinematic masterpieces. He strictly adhered to these principles in works such as the brilliant Psycho (1960) and the intimate yet imperfect Rope (1948).

But the crowning Hitchcock masterpiece of self-imposed limitation is Rear Window.

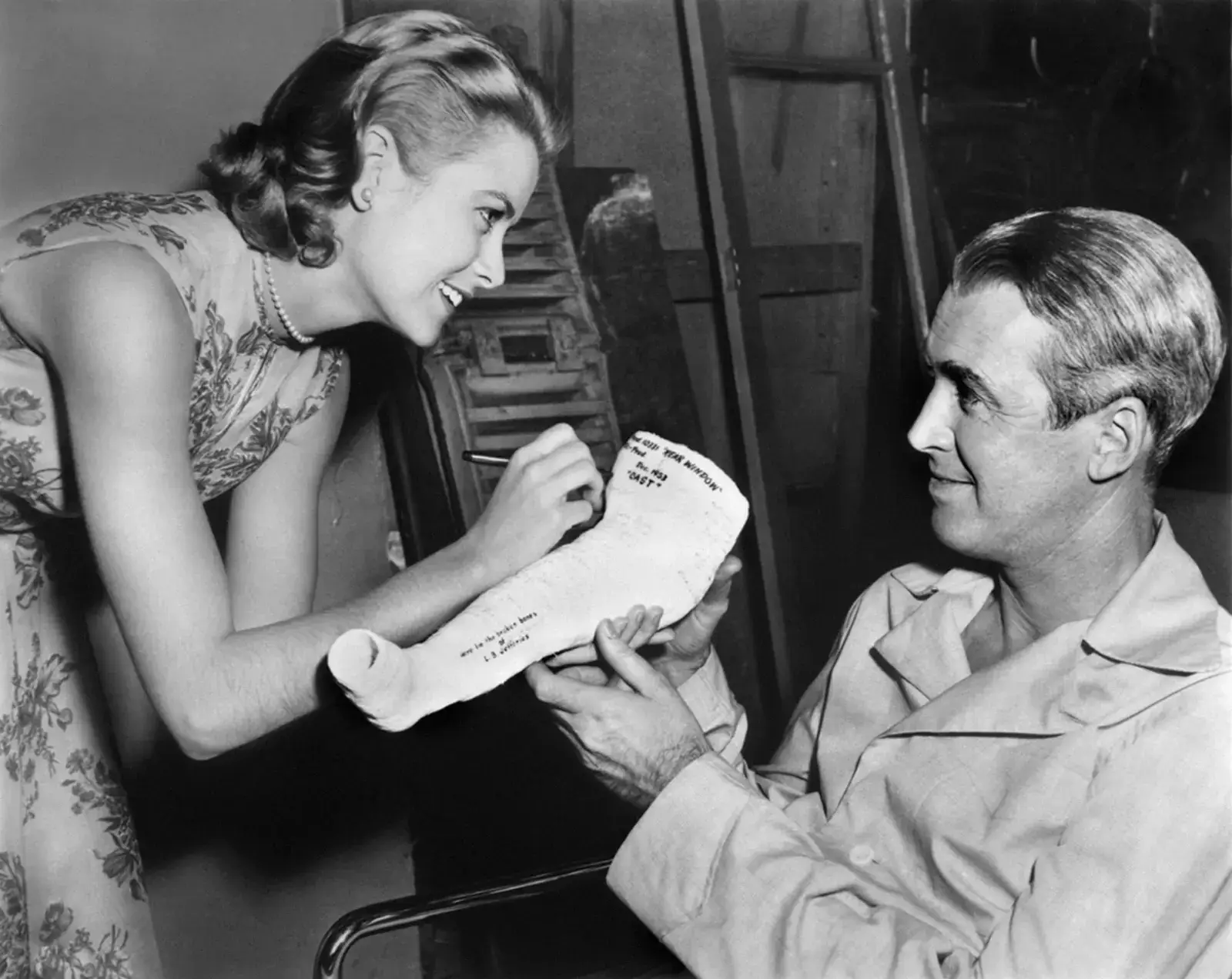

The brilliant career of photojournalist L.B. Jeffries—Jeff to his friends (James Stewart)—is suddenly interrupted. After an accident on the racetrack, our protagonist’s left leg is in a cast, and he’s confined to a wheelchair. His only pastime becomes looking out the window of his apartment at the building surrounding the courtyard. His daily boredom is interrupted only by visits from his nurse, Stella (the excellent Thelma Ritter), and his girlfriend, Lisa Fremont (the beautiful Grace Kelly). Amid Stella’s witty remarks and Lisa’s serious marriage plans (to which Jeff reacts rather coolly), his new, forced hobby—observing the apartment’s residents—takes center stage.

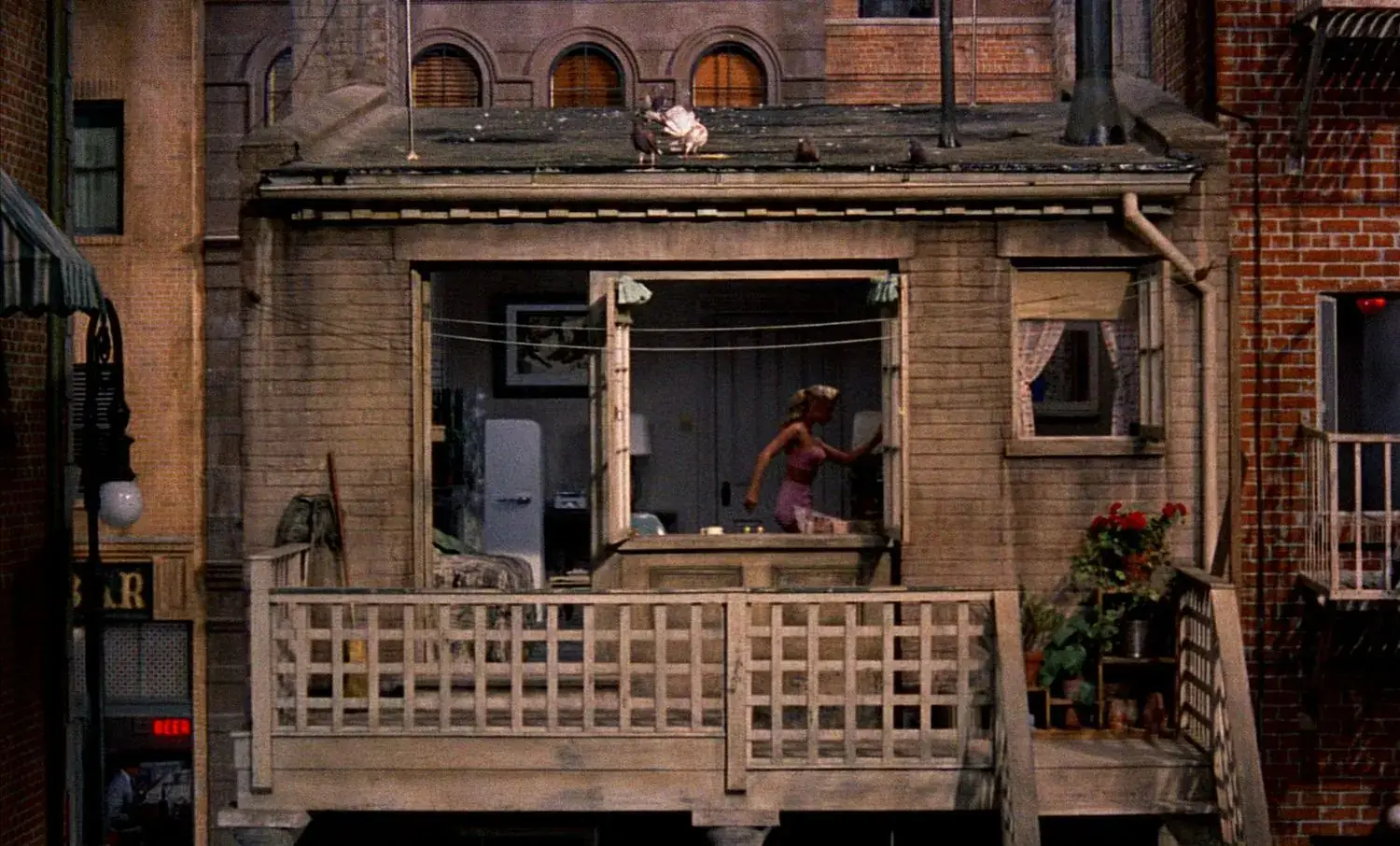

Among them are a young composer, an attractive dancer, a spinster drowning her sorrows in alcohol, a newlywed couple, an older couple who walk their dog in a basket straight from their balcony, and an eccentric sculptor. Over time, Jeff’s attention is drawn to someone else. A middle-aged couple across the courtyard seems to be going through rough times. She—Anna Thorwald—is gravely ill and rarely leaves her bed, while he—traveling salesman Lars Thorwald—seems tired of caring for his grumpy, moody wife. Jeff’s seemingly innocent voyeurism is put to the test one evening. Amid the quiet night and drawn curtains, there is suddenly a woman’s scream and the sound of glass shattering. That same night, Jeff sees Thorwald leaving his apartment several times, carrying a suitcase. But come morning, Jeff dozes off in his wheelchair, missing Thorwald’s exit—this time in the company of a woman. This is the only moment in the film where the audience witnesses something the main character doesn’t.

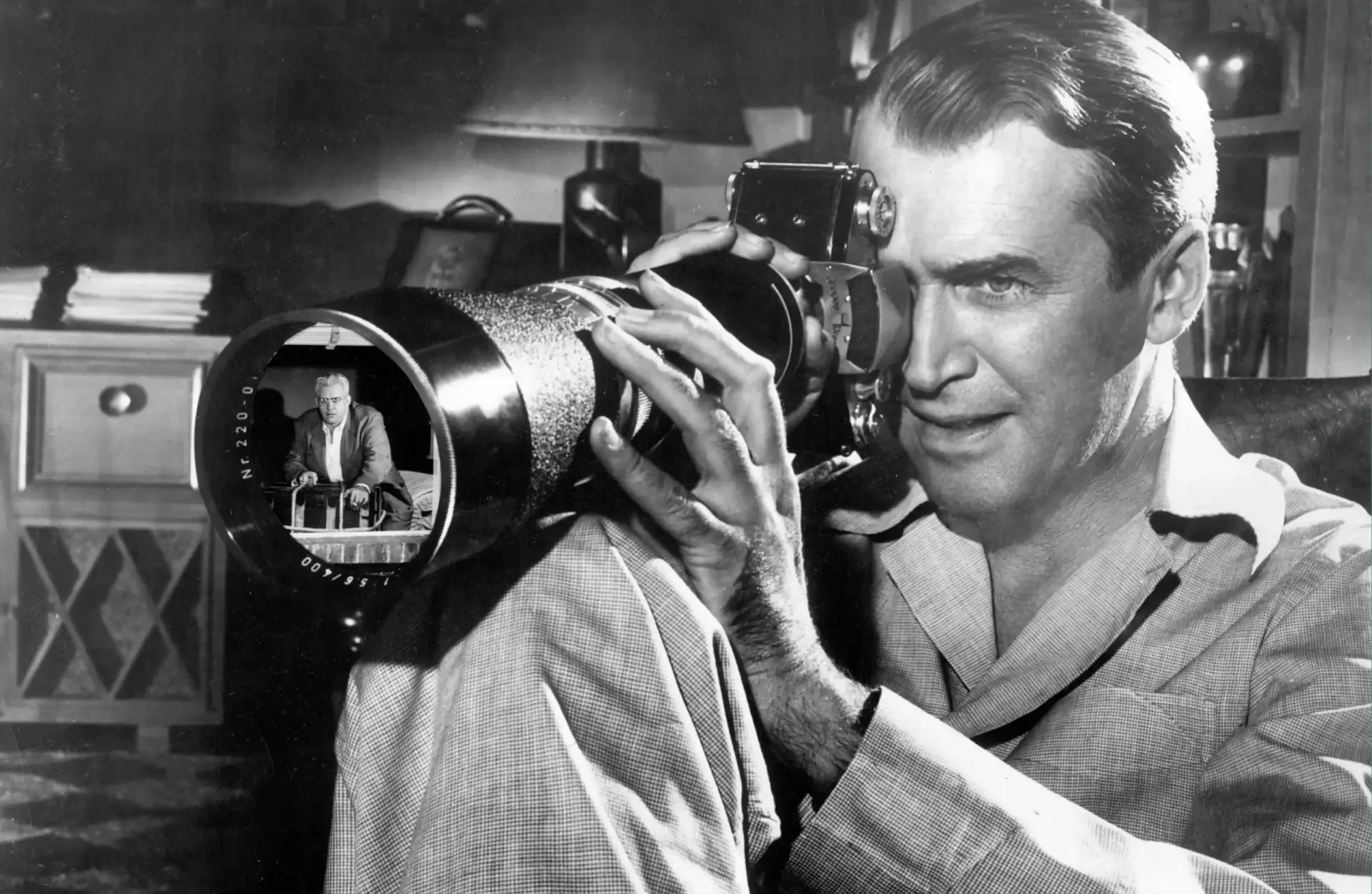

The next day, Jeff is disturbed by Thorwald’s strange behavior. Why is he wrapping a large butcher knife in paper? Why is he struggling to close a large suitcase? Why is he vigorously scrubbing the bathroom? And where on earth is Mrs. Thorwald? Jeff begins to suspect, no more or less, that a murder has taken place—that the poor man has killed his wife and now acts as if nothing happened.

Jeffries shares his suspicions with Stella (who, eager for excitement, quickly grasps the entire intrigue) and his fiancée. Lisa initially responds skeptically, but when she sees Thorwald’s behavior, she changes her mind. Jeff now only has to convince his old friend, LAPD detective Lt. Doyle, of the alleged murder. However, the officer has a simple explanation for Jeff’s theories: they’re just baseless delusions of a man who peered into others’ private lives. Undeterred by this assessment, Jeffries, with the help of Lisa and Stella, launches his own investigation. The catch is that, being immobilized, he’s not at risk. Unlike Lisa, who, in Thorwald’s absence, sneaks into his apartment without realizing the supposed killer is on his way home…

Decades before reality shows, Hitchcock made a film about the dangers of spying on others. An innocent pastime gradually turns into a true obsession based solely on suspicions, assumptions, and increasingly precise observation. Hitchcock accentuated this near-paranoia through unique uses of sound and visuals. The entire film is shot from Jeff’s apartment, and the camera leaves this place only a few times during two climactic moments: the discovery of the strangled dog and the film’s dramatic finale.

We don’t see close-ups of the opposite windows until Jeff uses binoculars or a telephoto lens. The soundscape features only street noise and the voices of the apartment residents. Even the music in Rear Window is only present when played by the tenants. These choices place the viewer almost directly in Jeff’s position. Without overusing subjective camera shots, Hitchcock performed a kind of experiment in double voyeurism on the audience. After all, what is watching a film if not observing someone’s life from a safe distance?

Casting the two leads in “Rear Window” was both clever and typical of Hitchcock. L.B. Jeffries is yet another outstanding performance by James Stewart, America’s favorite actor. Known almost exclusively for positive roles, Stewart plays a character gripped by a dangerous obsession, even encouraged by his fiancée. Perhaps Jeff sees his future in Thorwald, a man bored with marriage? After all, Lisa is eager for him to abandon his nomadic lifestyle and settle in Los Angeles. He, in turn, coldly rebuffs every attempt at discussing a future together. Yet Jeffries is a highly likable character, easy to relate to and join in the thrill of hunting down the suspected killer.

Lisa Fremont marks Grace Kelly’s second role with Hitchcock (after Dial M for Murder). Hitch was known for his interest in statuesque blondes, perhaps because his wife, Alma Reville, was a petite brunette. In his best films, these cool, striking blondes served to confuse and lead male protagonists astray. This was true of Ingrid Bergman (Spellbound, Notorious), Grace Kelly (Dial M for Murder, To Catch a Thief), Kim Novak (Vertigo), Eva Marie Saint (North by Northwest), Janet Leigh (Psycho), and Tippi Hedren (The Birds). Despite Kelly’s presence, her role in Rear Window is less colorful and ambiguous. Lisa Fremont, despite her fame as a model and fashion designer, is an honest girl dreaming of a normal life alongside her beloved.

Rear Window dazzles with technical perfection. Cinematographer Robert Burks, Hitchcock’s regular collaborator, tackled the monumental challenge masterfully. Since the entire film was shot on a single set, from which the rest of the scene was filmed, Burks achieved something extraordinary. This accomplishment is even more remarkable given Hitchcock’s filmmaking philosophy, which relies primarily on visuals. According to the director, dialogue is misleading, obscuring the plot, and often used as a necessary evil. Only visuals can convey the absolute truth of the cinematic world, carrying meanings that even the most elaborate dialogue cannot. Rear Window is one of Hitchcock’s fullest realizations of this principle.

The titular courtyard, which appears to be a real structure, was constructed as an enormous set in Paramount’s largest soundstage, with the floor dug several meters deeper to accommodate Jeff’s first-floor apartment at the actual ground level of the studio.

Hitchcock directed actors in an unusual way, never leaving Jeff’s apartment set. The remaining residents were directed via radio devices and small earpieces painted in flesh tones. The set of Thorwald’s apartment was so meticulously crafted that it included working electrical and plumbing systems. Georgine Darcy, who played Miss Torso, a ballet dancer, was so impressed with her setting that she stayed in her character’s apartment throughout the month-long shoot. Hitchcock, as was his custom, made a cameo on-screen for a few seconds in the film’s 25th minute, winding a clock in the composer’s apartment. His audiences knew of his tradition, prompting him to appear earlier in his later films to avoid distracting viewers from the story.

Rear Window cemented Hitchcock’s reputation as a master of suspense cinema. The film received Academy Award nominations for Best Director, Screenplay, Cinematography, and Sound. For nearly 30 years, due to copyright issues, Rear Window was unavailable, along with four other works from the same period: Rope (1948), The Trouble with Harry (1955), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), and Vertigo (1958). Finally, Hitchcock repurchased the rights to these five films in the last years of his life. After the director’s death in 1980, his daughter Patricia (who appeared as the secretary in Psycho) re-released these films to audiences worldwide.

Rear Window is an extraordinary film. It begins as a lighthearted story and gradually transforms into a fascinating tale of the darkness within human nature. Alfred Hitchcock, the master storyteller, created a masterpiece that can be viewed as a crime story, an intimate, engaging drama, and a moral tale suggesting that evil can lurk even in the banal view outside your window.

No one is safe. Neither the neighbor across the courtyard nor we, seemingly passive witnesses to small human dramas. The devil doesn’t have to be all-powerful or sit atop the social food chain with a name like John Milton. Sometimes, seeing him just requires looking a bit too long out your own window.