NORTH BY NORTHWEST Deciphered: Hitch’s Unparalleled Genius

– We won’t settle this matter successfully this way, Mr. Kaplan.

– My name is not Kaplan!

– Think it over…

This situation is observed from a distance by two unpleasant-looking men, for whom this chance event is crystal clear — the bellboy has found Kaplan. A bewildered Thornhill is kidnapped and taken to the remote estate of Lester Townsend, who believes he is facing George Kaplan. Thornhill refuses a vague proposition of cooperation, is forcibly intoxicated by Townsend’s thugs, and placed behind the wheel of a car. He narrowly escapes with his life and initiates a visit from the prosecutor to Townsend’s house. There, as one might expect, no one — not even Townsend’s wife — knows anything. Roger Thornhill decides to solve the mystery of the false identity attributed to him on his own. Ladies and gentlemen: North by Northwest.

Following Townsend’s trail, Thornhill goes to the UN headquarters, where he meets his persecutor, who is a completely different man with the same last name. At the decisive moment of their conversation, the real Townsend is stabbed, and all clues point to poor Thornhill, who saves himself by fleeing. Meanwhile, it turns out that George Kaplan is a fictional creation of American intelligence officials, who, by inventing a fake agent, aim to catch a certain Vandamm, the same man who had posed as Lester Townsend. But unaware of this grotesque situation, Thornhill escapes by train to Chicago, where he meets the mysterious blonde, Eve Kendall, who knows suspiciously much about him. After spending the night together, Eve helps Thornhill leave the train, but the supposed George Kaplan has no idea that his travel companion is working closely with Vandamm…

Alfred Hitchcock is commonly known as a creator of dark thrillers. Few people know that Sir Alfred began his directing career with melodramas, where he learned the basics of filmmaking. It wasn’t until the 1930s that Hitchcock fully shifted to inventive crime and suspense stories. His legendary sense of humor rarely found its way into the broader structure of his scripts. Only with The Lady Vanishes (1938), Hitchcock’s best British film, did humor become more prominent. After moving to the U.S., Hitch didn’t create a true black comedy until 1955 with The Trouble with Harry. The 1950s were mainly a time of his greatest masterpieces — Strangers on a Train (1951), Dial M for Murder (1954), Rear Window (1954), To Catch a Thief (1955), and Vertigo (1958).

Hitchcock ended the 1950s with North by Northwest (1959), a film that can be grouped with the aforementioned masterpieces. What set it apart, however, was the unexpected dose of humor and wit, which brightened and enhanced the script — a typical Hitchcock tale (by the way, it was an original screenplay, a rarity among the literary adaptations that make up the vast majority of his films). Once again, Hitchcock told his favorite story of an ordinary man caught in an extraordinary and seemingly overwhelming situation.

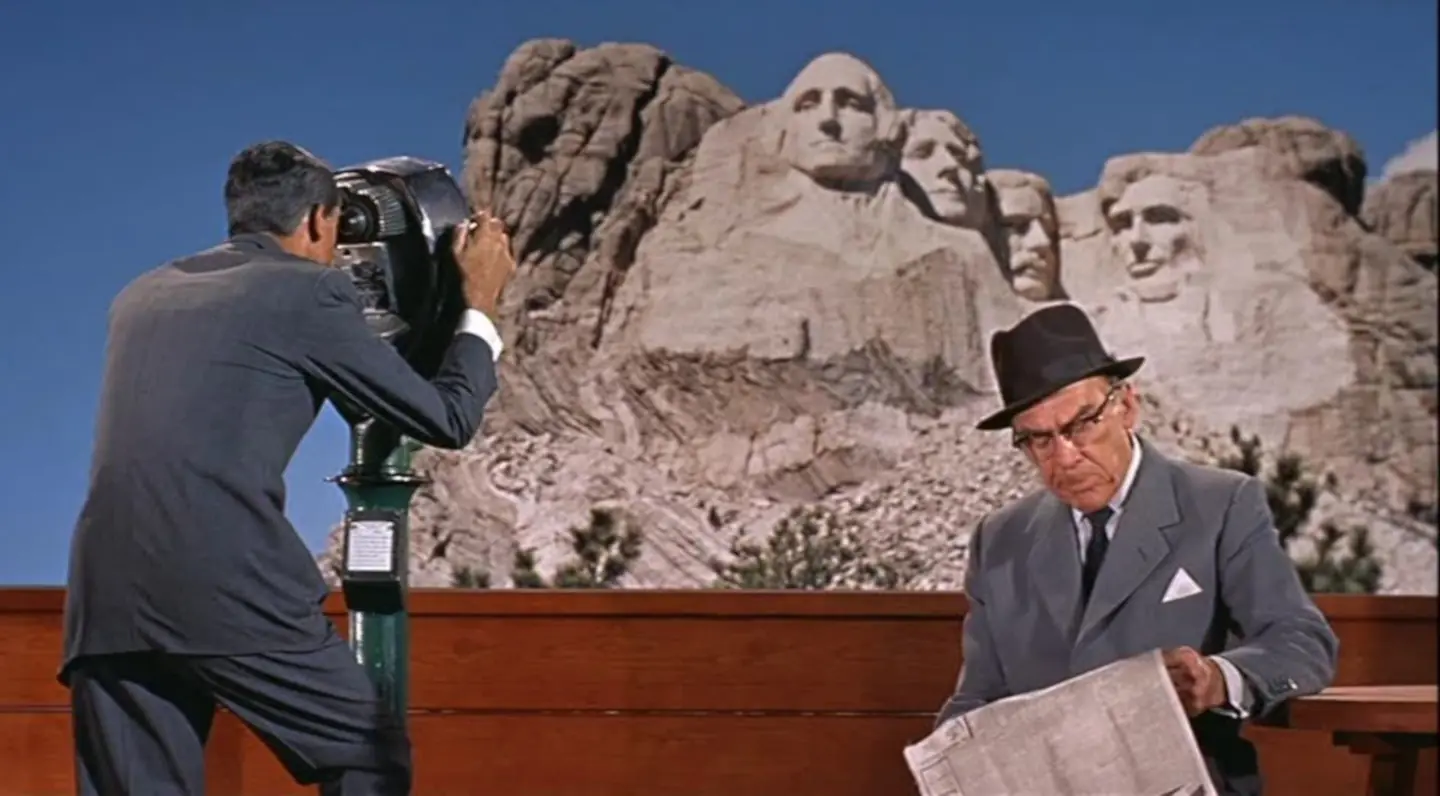

At the beginning of the 1950s, Alfred Hitchcock signed a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to make the film The Wreck of the Mary Deare. The screenplay adaptation was written by Ernest Lehman, whom Hitchcock had met through his friend, the distinguished composer Bernard Herrmann. The planned film never materialized, as Lehman struggled creatively while writing the screenplay. Meanwhile, Hitchcock had two highly cinematic ideas in his head — a chase across the vast stone carvings of Mount Rushmore and the murder of a diplomat at the UN headquarters in New York. Without losing the contract with MGM, the two decided to make a completely different film than the one outlined in the agreement.

To justify these scenes within the plot, they were missing “only” the rest of the script. At a meeting with the studio’s executives, Hitchcock manipulated them with the same cunning precision he used on his audience. With only a vague outline of the script in mind, the director presented his new project as fully ready for production, then invited them to the premiere and left. MGM’s bosses were so bewildered and intrigued by the words of the Master of Suspense that they accepted simultaneous production of North by Northwest and The Wreck of the Mary Deare. Meanwhile, Hitchcock only intended to make the former. The unusual title North by Northwest indicated the geographic direction of the protagonist’s journey.

Cary Grant, whose real name was Alexander Leach, played the leading role for the fourth time in a Hitchcock film. The 1950s were supposed to be his farewell to acting, but Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief brought him triumphantly back to the screen. Five years later, Grant starred in a Hitchcock film for the fourth time, although James Stewart, Hitchcock’s other favorite actor, had a strong desire for the role of Roger Thornhill. However, the director preferred Grant (the studio felt the same, as Vertigo, the previous Hitchcock-Stewart collaboration, had unexpectedly flopped at the box office; only years later was Vertigo hailed as a masterpiece). During the filming of North by Northwest, Cary Grant was 55 years old, but his incredibly well-preserved appearance led to one of the most amusing casting curiosities in cinema history. Roger Thornhill’s mother was played by Jessie Royce Landis, an actress who was actually one year younger than Cary Grant! Yet, their scene together in the hotel room is entirely convincing.

The main female role in North by Northwest was cast according to Hitchcock’s typical criteria. The statuesque Eva Marie Saint is yet another iteration of the femme fatale — a blonde heroine who complicates the male protagonist’s life. Like her famous predecessors, Grace Kelly, Ingrid Bergman, and Kim Novak, Eva Marie Saint masterfully showcased the sophisticated, cold charm of her duplicitous character. In the scene of Thornhill and Eve Kendall’s first meeting, Eva Marie Saint delivered the line, “I never make love on an empty stomach.” But due to censorship, this bold line for its time was re-dubbed to “I never discuss love on an empty stomach.”

In North by Northwest, Hitchcock abandoned formal experiments with long takes, focusing his mastery on a more traditional visual style. It’s important to remember, though, that Hitchcock’s “traditional” approach meant creating rules that would become the standard for the genre. Hitchcock’s films established narrative and visual conventions, which might seem repetitive to young viewers unfamiliar with his work. How many times have we seen a lone protagonist fighting against the world, deceptive women in his path, thrilling chases in the most unusual places, or the nerve-wracking suspense of knowing more than the on-screen character? These elements of cinematic language were invented or brought to perfection by Hitchcock. As was customary, the director made a brief cameo appearance, this time as a man missing a bus just after the opening credits saying, “Directed by Alfred Hitchcock.”

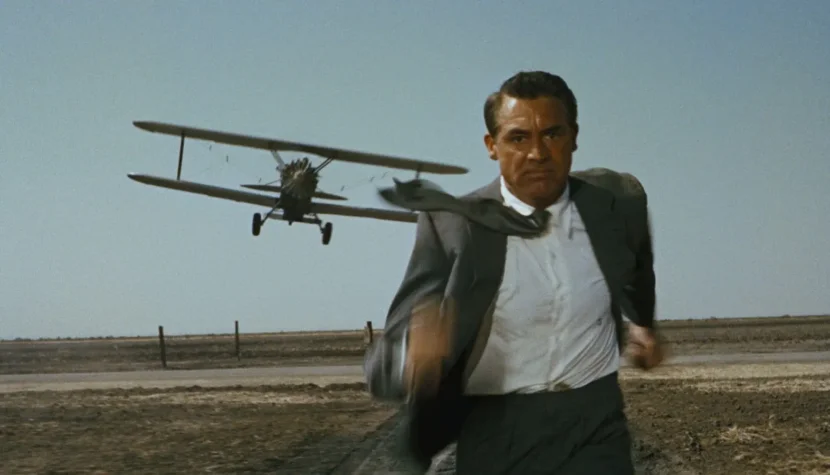

North by Northwest contains some of the most memorable and frequently cited scenes in cinema history. What I love most about Hitchcock is his visual storytelling style, where the story unfolds purely through images, without a single line of dialogue. This most challenging narrative technique is best exemplified in the frequently referenced sequence (including in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade when Indy and his father escape from machine-gun fire), brilliantly filmed in an open field where Thornhill, waiting for the non-existent Kaplan, is mercilessly attacked by a pilot in an airplane. This sequence begins with several minutes of anticipation, during which nothing happens — Cary Grant stands on the highway, looking around. Yet, even in such a scene, Hitchcock manages to captivate the viewer and make them hold their breath in anticipation of something extraordinary.

North by Northwest ‘s finale, set on Mount Rushmore, also went down in history. Hitchcock did not receive permission from the Department of the Interior to film at the location, as they did not want to desecrate the carved heads of the Founding Fathers of American democracy with a criminal intrigue. The authentic setting was only used for wide shots, filmed several kilometers away from the monument. The entire climax was staged with studio sets, ensuring the actors moved only between the heads. Known for breaking social taboos, Hitchcock treated American sanctities with exceptional respect, although in Psycho, shot a year later, audiences for the first time heard the previously forbidden sound of a toilet flushing in Norman Bates’ motel (censors sent the scene back for editing, but Hitch didn’t cut the sound and returned the film unaltered with a statement claiming he had made the changes; the censors didn’t review the film again and trusted him on his word). While making a film about criminals, Hitchcock himself broke the law. In one scene, Roger Thornhill goes to the UN headquarters, where filming was strictly prohibited. To capture this scene, Hitch hid a camera in a car disguised as a carpet-cleaning vehicle, and from this concealment (under the unsuspecting eyes of federal agents), he filmed Cary Grant in front of the United Nations building.

The film’s imaginative opening credits, among the best in cinema history, were designed by Saul Bass, a conceptual film artist with an extraordinary imagination. Bass also created the credits for Vertigo, Psycho, and The Birds. The film is accompanied by the equally famous score of Bernard Herrmann, a genius of film music and composer for seven Hitchcock films (eight if you include his consultation on the electronic sounds for The Birds). Herrmann disliked catchy, clear melodies in the style of Elmer Bernstein. His forte was violent, monumental “sound walls,” overwhelming the listener with their fascinating structure, perfectly illustrating the dark plots of Hitchcock’s masterpieces. Despite his use of fairly intense orchestral means, the main theme from North by Northwest is one of the most famous motifs in film music history.

For film technique enthusiasts, the use of the VistaVision format in the film, produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, was surprising. The 1950s were a time when studios fought over viewers, who were gradually being taken away by television. To fill cinemas again, engineers from 20th Century Fox adopted the French widescreen format CinemaScope (with an aspect ratio of 2.35:1). Other studios followed, one by one creating their own widescreen presentation formats. In 1954, Paramount introduced its own VistaVision system (with a 1.66:1 aspect ratio), which Hitchcock utilized for To Catch a Thief and Vertigo, shot for Paramount. This technically superior format (occasionally still used today for capturing visual effects) was carried over by Hitch to MGM, even though that studio had not previously used VistaVision, promoting its own 1.85:1 format achieved through artificial masking of the standard 35mm frame. Another curiosity was the unusual green background of the studio’s logo, opening the screening of North by Northwest.

Speaking of technique, it’s worth mentioning the advanced visual solutions of the time. Hitchcock employed visual effects on an unprecedented scale in his own work, using optical extensions to expand the frame with non-existent landscape elements. Many wide shots were composed using hand-painted backdrops that extended the frame. This technique is particularly evident in the scenes where a drunken Thornhill is put behind the wheel of a car, his escape from the UN, scenes in front of Vandamm’s villa, and the finale at Mount Rushmore.

The most challenging shot was the aerial view of the barren field just before the airplane attack. A Californian city was visible on the horizon, but Hitch had envisioned an endless expanse of farmland. The shot was captured from a gondola mounted on a crane, which had to be firmly secured with four cables attached to the ground. Only this way could a perfectly stable frame be achieved, ensuring the proper superimposition of the painted horizon line. In the airplane chase sequence, another visual trick was used. All close-ups of Cary Grant dodging gunfire were filmed in the studio, with the actor playing in a minimalistic set in front of a screen displaying rear projections.

North by Northwest once again confirmed the genius of Alfred Hitchcock, his unparalleled skill in telling captivating stories, his complete control over the viewer’s emotions, and his ability to infuse a thrilling plot with deeper meaning while lightly and gracefully presenting comedic situations (though the unexpectedly humorous struggle for Thornhill’s life on the road was filmed by the film’s co-producer Herbert Coleman). If today, watching films with Bond, Harry Tasker, or Martin Riggs, we marvel at the seamless blend of excellent comedy and dynamic action cinema, let’s not forget that we owe it all to Hitchcock, whose films were ahead of their time.