BLADE RUNNER 2049 Explained: What It Means to Be Human

…, still resonate with similar power in the sequel released 35 years later. As it turns out, the passage of time has not brought the expected answers, and the analogies present in the original could easily be transferred to the contemporary film. Although technologically and evolutionarily we are far from the vision proposed in 1982, it seems that we understand the issues raised there better and better, even if we pretend that they do not concern us.

The text describes the key plot elements of both parts of Blade Runner.

The reflection of these issues can already be found in the outline of the world depicted in Blade Runner, as a planet devastated by an ecological crisis may be a certain grim alternative to our future. The pervasive smog in the first film—surrounding the city, hovering above it, and also penetrating its streets—is one of the many reasons why rain so often falls on the characters. This Earth is gradually depopulating, and humanity, fleeing from the effects of its actions, leaves mainly the lower social classes, rats, and cockroaches behind. It’s no wonder that the first part is so claustrophobic and at times resembles a vision straight out of a horror movie—its world is a trap set by people driven by greed on themselves. And although we find many more open spaces in Blade Runner 2049, Denis Villeneuve, aware of the ecological manifesto present in the script by Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples (and also Michael Green in the second part), expands the perspective to include even the sand-covered Las Vegas.

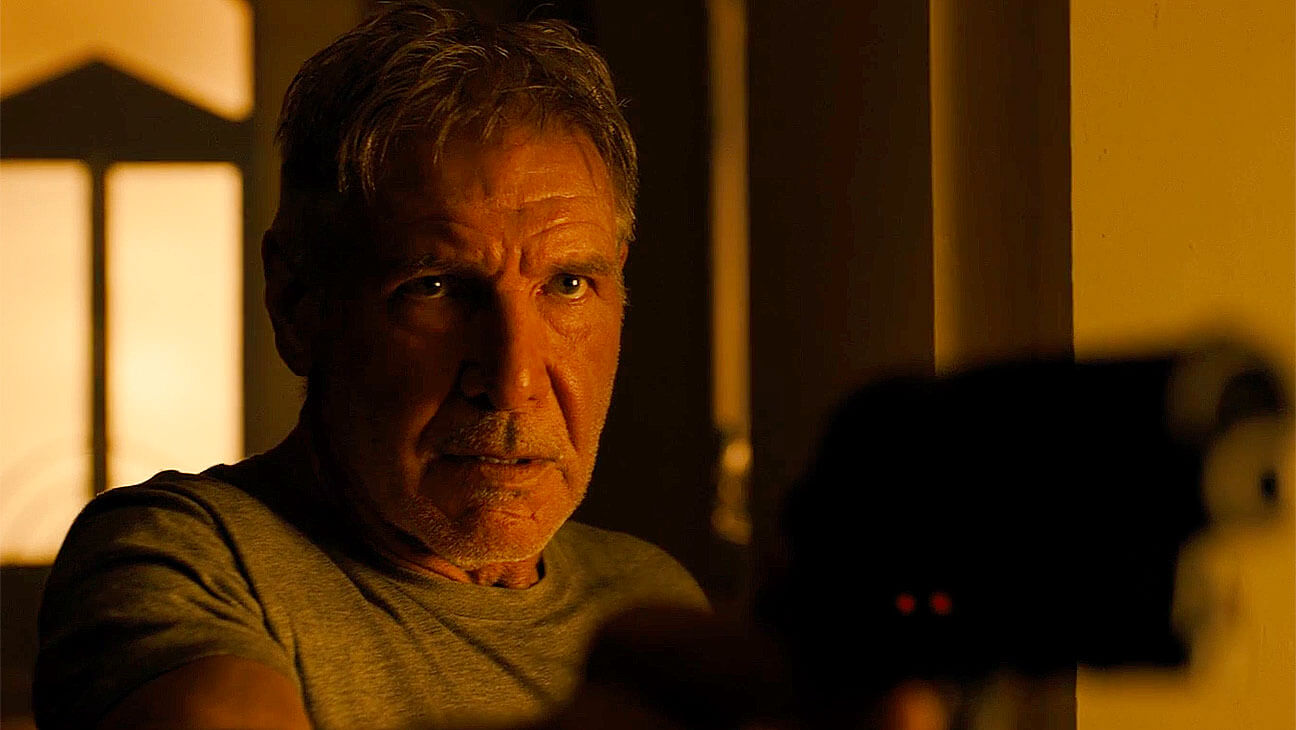

It’s notable that the replicants, who fled to learn more about their existence, come to a world from which the human species is eagerly escaping. Pursued by the aging process, deliberately accelerated in their case compared to ours, and by the authorities in the form of Rick Deckard, played by Harrison Ford, they attempt to find an answer to the question of whether they can be saved from impending death. The thesis about striving for immortality would be an overstatement here, but the fact that similar doubts keep us awake at night, regardless of origin, brings us closer to the group of androids represented by Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer). Unfortunately, the replicant receives information about the inevitability of his departure just before the third act of the story and is forced to come to terms with his fate.

As John Truby explains in The Anatomy of Story: The true opponent not only wants to prevent the hero from achieving his goal but also competes with him for it. What is the hidden goal of both Batty and Deckard? To be free. In a conversation with his superior, the protagonist refuses the assignment to murder the fugitives from the start—yet he is faced with a fait accompli, and his negative response doesn’t really matter. You have no choice, says the mustachioed man with a smile. In contrast, Batty stopped taking orders even before the film’s events began. When Sebastian tells the two androids to “show what they can do,” he informs him that they are not computers, clearly indicating that they will not do anything against their will. Thus, the ending, in which Deckard not only fails—after all, he nearly dies in the confrontation with the opponent—but also completes the investigation he never wanted to undertake, paradoxically turns out to be a triumph for the replicant. For a robot reconciled with his fate ultimately passes the test of empathy and saves his opponent, aware that this additional death would be pointless. Moments later, in a speech that mixes sadness with grim fulfillment, he marvels at how much beauty he saw during his short life, ending with an ellipsis on how much more he could have seen if only given the chance.

Moving on to Villeneuve’s film, it would not be particularly insightful to state that the officer K (Ryan Gosling) depicted there is much closer to Roy Batty than to Rick Deckard. Setting aside the obvious categorical affiliation (it becomes clear early on that K is a replicant), the new Blade Runner also tries to lead a “human” life and, as a result of a series of events, becomes part of the leitmotif of the duology. A seemingly trivial assignment to kill (in this world called “retirement”) a free replicant gradually turns into a huge web of intrigue when investigations into the remains of a woman buried in his garden reveal that she was not only an android but also an android who gave birth to a child.

K’s superior has no doubt about the need to keep the information about the unknown daughter or son of the robot secret. The world is built on a wall. The wall divides species. Tell one side that there is no wall, and you will bring war or slaughter upon us. This opens the film to interpretation as a social commentary on racism—not the only premise for such a reading, by the way. Just look at how the Blade Runner is treated in the company’s headquarters and the hard-to-overlook signs on his apartment door. Racial divisions, which may have disappeared from interhuman politics in this world, have certainly been transferred to the realm of interaction with replicants. There is a suggestion that regardless of our condition as a society, we will always find a conflict for ourselves. Moreover, the words of the chief clearly convey that the existence of opposing factions is the foundation for maintaining peace.

This is not the only social commentary present in Villeneuve’s work. At one time, Blade Runner 2049 was accused of misogyny, causing a small storm in the film criticism community. Such a thesis can be found in the reviews of Charlotte Gush and Anna Smith, as well as Tim Hayes. Not that there are no grounds for this—let us recall that one female character is a prostitute, another a murderer working for a blinded-by-ambition magnate, a third embodies the vision of a servile housewife, and a fourth, despite her high position, dies cruelly. In response to the accusations, the director explained that toxic masculinity is part of the depicted world and had to portray it regardless of his sensitivity. Such justification is supported by the film’s visible, aggressive neon billboard pornography attacking our eyes. Before considering this as a step too far—let me point out some contemporary music videos of popular music performers.

Having mentioned the servile housewife—she is played by Joi (Ana de Armas), a program designed to serve as a life companion. The fact that she mimics the stereotypical guardian of the home hearth reflects officer K’s inner desires. Does this mean he is a misogynist? That’s not what I mean—he is simply an android wanting to become human. Joi’s task, in this case, is to adapt to his ideas of ideal marital life—and since he has no family patterns to draw from, it becomes obvious that he will replicate a vision rooted in human culture. A vision of a woman serving a meal to a man returning from work. Naturally, the protagonist’s attempts to “humanize” himself will only intensify when he finds crucial evidence for the investigation.

In the first film, the replicants lacked memories—they were a kind of tabula rasa. Over the course of 40 years, this has changed: echoes of the past reverberate in the heads of Wallace’s androids (played by Jared Leto, the brilliant inventor whose corporation took over Dr. Tyrell’s status), constituting a cruel joke of the creator for them. The childhood story about a figurine hidden in the basement is merely an anecdote for K—at least until it turns out that he is dealing with a real memory rather than a fabricated illusion. Upon discovering this secret, he fails the replicant test for the first time. He is withdrawn from service and is to await the arrival of the authorities (presumably for accelerated retirement). Officer K, convinced he is neither human nor a robot—a new link in evolution—this time does not intend to follow orders and sets out in search of Rick Deckard.

On the phenomenally realized and filmed, intensely orange-bathed desert of Las Vegas, many film issues will be resolved: Joi will be literally crushed, Deckard taken over by Wallace’s corporation, and officer K, saved by the rebel faction, will learn the truth about his role. For now, let’s focus on this second event, as it cements another important theme of the film. The aforementioned magnate is driven by an obsession with Dr. Tyrell’s legacy, so the android loyal to him has been watching K’s investigation from the start. Although the inventor has created machines evidently better in practical application than his predecessor, he still fails in terms of procreative ability. His greatest failure occurs when he believes he has perfectly recreated Rachael (rejuvenated to the point of resembling herself from years ago, Sean Young), only to actually make a mistake—Deckard notices she has different eyes. Thus, Wallace, mired in madness, simultaneously represents the biggest on-screen misogynist and a kind of observation about the nature of the most toxic representatives of the male community. It is undeniable that he perceives female characters primarily as incubators, and in his pursuits, he seeks to create beings capable of artificially extending life.

It is worth noting the presence of religious symbolism, particularly relating to Christian faith, found in both the original and its sequel. Present in both parts are deceitful, Judas-like kisses, the resemblance of replicants to angels (whose sole purpose is to serve), and scenes with clear visual citations—such as Batty holding a dove at the end of Blade Runner or Officer K being touched by a crowd of children in Blade Runner 2049. The sequel also introduces the theme of creationism, a driving force of the plot, and thus the crossing of boundaries between humans and divine beings. Especially in the character of Wallace, we can perceive a God complex and his attempts to overturn the age-old natural laws.

Let’s return to Officer K, who, during his confrontation with an underground organization of rebels, learns a devastating truth—that the mysterious child is actually the “memory factory” worker, Dr. Ana Stelline (Carla Juri). His memories are nothing more than fabrications, and the hope of being someone (or something) more, which he had held over the past few days, vanishes instantly. It turns out that he was partly fulfilling the objectives of yet another side of the conflict, remaining a puppet being pulled by various strings the entire time. Dying for a cause is the most human thing we can do, a rebel tells him while simultaneously issuing another order: kill Deckard.

At this point, the protagonist is already tired of the constant control. Like Batty from the first film, he makes the decision to save Deckard not as an act of duty, not due to the suggestion of the rebel group, and certainly not as a consequence of destiny, but for the most trivial of reasons—decency. When he brings Deckard to meet his daughter, whom he has never seen, and Deckard asks him why he did it, K does not respond, only smiling mysteriously. In this case, an answer is unnecessary because our actions do not need to be rational. I will spare you the truism about freedom of choice as the foundation of humanity, as I do not believe that after the events depicted in the film, K still cares about being human. I think, at that moment, he only cared about one thing: being free.

When it comes time for these crucial reactions, far more important than the answer to the question of what to do with a tortoise turned on its back, all three of the most significant replicants in the Blade Runner world pass the empathy test: Batty, when he saves Deckard from falling, K, when he reunites the lost father with his daughter, and Rachael, when she sheds tears upon learning the truth about her origins. The ability to make decisions and thus escape from the fate of being a slave seems to me the key theme of the analyzed duology. This theme resonates even more with contemporary issues, as feminist and equality movements continue to fight for the right to self-determination—whether it concerns social equality, abortion rights, or issues such as gender reassignment. Then, a sad truth emerges: the onscreen parallel between the fate of the replicants and minorities may be even too conservative to fully reflect current problems.

There is undoubtedly something moving in the scene where K learns he is not the mysterious child. Beyond the probable emotional connection that makes us feel the android’s disappointment firsthand, the protagonist becomes, in a way, a champion of the “non-exceptional.” Although our birth often determines our social or financial status, we are never “destined” for success—we can only work for it. Consequently, Officer K does not need to open a new evolutionary ladder to do the right thing—in the end, he makes his decision based on his own, far less monumental experiences. It turns out that sometimes you don’t have to ponder what defines humanity, because it is still just a definition. After more than 40 years, it turns out that Batty was wrong when he said that all these moments will be lost like tears in rain. The consequences of the actions of the two androids live on only because they chose wisely at the crucial moment.