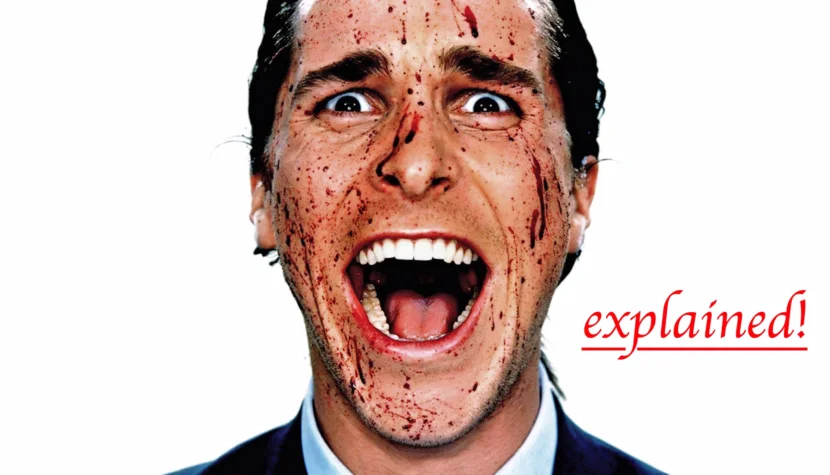

AMERICAN PSYCHO. Controversial Shocker Explained

Significant films for this genre emerged during this time, including Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs, David Fincher’s Seven, Rob Reiner’s Misery, Martin Scorsese’s remake of Cape Fear, and Philip Noyce’s The Bone Collector.

A similar ambiguity is present in the sequence accompanying the opening credits of American Psycho. In it, the same two orders are confronted. In successive close-ups, we see plates being laid on a white tablecloth. Against this backdrop, a red line appears (immediately evoking blood), followed by a kitchen knife. The juxtaposition of these two shots transforms us into witnesses to preparations for a crime. Mary Harron plays a game of associations, deliberately leading us down an incorrect path of interpretation. Only later is the mystery solved: we are merely watching chefs preparing a dish in a restaurant. This sequence aptly reflects the duality of the main character’s nature. The camera shot resembles the perspective of someone sitting at the table. This allows us to understand how Patrick Bateman interprets the world around him. Every action and object acquires a completely new meaning in his eyes. Patrick Bateman eventually starts getting lost in the city’s space, seeing his own reflection everywhere. The subsequent murders are not only a form of reaction to this state.

American Psycho also addresses the theme of the double, a concept present in culture for centuries, in a very original way. Importantly, the issue of identity loss affects not just the main character but the entire group of American stock market players. They all look the same, are the same age, wear the same suits, have identical apartments and identical sexual partners, spend their free time in the same way, and make a living similarly. This social group has succumbed to strong uniformity. The film’s characters continuously confuse each other’s names, pretend to be someone else, and incessantly compare themselves to the person next to them. It is a hermetic environment devoid of individuality. The individual loses their subjectivity in favor of the whole group. It is not just a doubling, but a multiplication of the character. The difference between Patrick Bateman and Paul Owen is as imperceptible as that between their business cards.

Attention should also be paid to the role of Detective Kimball (Willem Dafoe), who not only legitimizes Bateman’s existence. Patrick, sinking deeper into madness, creates the figure of the investigator in his mind to convince himself that his murders indeed took place. Kimball serves as the defender of Patrick Bateman’s consciousness, needing to validate his actions. The main character will only feel safe when someone else notices his crimes and holds him accountable. The specter of real punishment is meant to convince him that he has not gone insane. The investigation led by Kimball is supposed to be evidence for Bateman that he has not lost himself in an imaginary world. Additionally, the detective, representing justice, visualizes the guilt emerging within Bateman. The main character feels he has gone too far. Kimball is, of course, also Bateman’s double, another reflection of his personality: not the first, nor the last. The detective’s character is another step towards madness; the subsequent crimes cannot be ignored – he knows he must face punishment. Patrick cannot accept that he has ceased to distinguish the real world from the imagined one. This is another obstacle distancing Bateman from mental stabilization.

The Idea of Patrick Bateman

This is the idea of Patrick Bateman, a kind of abstraction, but it’s not the real me, it’s just some illusory being. I can hide the cold gaze and when we shake hands, you might feel a firm grip, maybe even get the impression that we lead similar lives.

The plot of American Psycho does not provide many clues to logically explain the genesis of evil. Bateman does not kill ritually or methodically; he doesn’t kill for someone. His victims are innocent and random. The only exception is Paul Owen – murdered due to Bateman’s absurd jealousy – as he had a more attractive business card design and a reservation at a more prestigious restaurant. Patrick Bateman feels cornered, exhausted by the competition with everything around him. The slightest impulse is enough for him to feel threatened. The crimes are an exaggerated expression of his fears. This is the only way he can defend himself. Bateman’s brutal drawings in his notebook become his reality.

In the history of cinema, there have already been characters who, like Patrick Bateman, realized themselves through violence. One such character was Alex DeLarge from A Clockwork Orange. He also plays two roles in his life: during the day he lives with his parents and pretends to be a good son, while at night he becomes a perverse criminal. Like Bateman, DeLarge does not contest anything. In his case, it is also not about rebelling against institutions like political power, the church, or family. The protagonists of these films use violence as a form of play, testing their limits, torturing another person to see how far they can go. Violence serves a therapeutic function for them, stimulating and maintaining their mental balance.

Of course, in the history of culture, characters like Alex DeLarge or Patrick Bateman are interpreted as social order contesters and rebels. Their aggressive attitudes are convenient for such an analysis. However, when viewed from the perspective of the world depicted in the film, we must revise our opinion because their rebellion has completely different motivations. They treat violence as play, a method of self-expression, and most importantly – gratification. They do not follow any plan in hurting others, nor do they act according to any pattern. Violence becomes a disabling addiction, and as a result, they turn out to be victims themselves, being prisoners of their pathological imaginations.

American Psycho: Crime Without Punishment

In the end, Bateman begins to doubt himself. He is not ashamed of his deeds, nor do they provoke moral or ethical dilemmas in him. The protagonist only wants to be verified by another person. He wants to hear a condemning sentence on himself, but not for any sense of justice, only to affirm that he is not functioning in a fictional world. Bateman wants to be sure he is experiencing the same reality as others. He wants to be sure he actually hurt someone. Only when his perspective is rejected and deemed untrue will Bateman react with deeper critical reflection. In the voiceover, Patrick Bateman states: There are no more barriers. I have overcome uncontrol, madness, depravity, the evil, chaos I caused, and my indifference to it all. I am filled with sharp pain. I want to pass my pain onto others. I won’t let anyone escape. Even after this confession, there was no catharsis. Punishment is still deferred. And I do not know myself more deeply. Nothing new comes from my words. This confession was meaningless.

The protagonist of American Psycho sees himself as a martyr, someone who has understood the meaning of human life. If there is no punishment, we cannot expect anyone to be rewarded for living rightly. Bateman completely devalues human life. He situates himself even beyond the concept of hope (rescue) because it too does not exist. Moreover, Bateman realizes that this awareness also does not improve his situation, giving him no advantage over others. Bateman possesses knowledge that cannot be used in any way. There is no one to pass it on to. Nihilism turns out to be the prevailing ideology, one that everyone is doomed to. Patrick Bateman will never be punished for his crimes – imagined or real. No one will judge him. In Ellis’s book, Patrick Bateman describes himself with these words: My personality is merely an endless sketch, and my lack of heart is deep and solid. My conscience, my compassion disappeared long ago (…).

Bateman is merely a construct, a sketch of a man: without color or substance. He cannot justify his existence, give it purpose. His life is random and unnecessary, unimportant. But is it really? Maybe it is not Patrick Bateman who narrates this story, maybe someone controls this absurd world from above and decides to introduce the unaware Patrick. This interpretation is suggested by the quote opening Bret Easton Ellis’s novel from Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground:

I wanted to present to the public – somewhat more explicitly than usual – a certain person from the recent past. This individual belongs to a generation that is now living out its days. In the chapter titled “Underground,” this person describes himself, his views, and efforts to explain why he appeared, indeed had to appear among us.

Bateman turns out to be a product of an oppressive society. American Psycho speaks with extreme pessimism. All values are devalued, man proves to be completely helpless, and his life is strikingly trivial. Conscience cannot be anyone’s salvation, a chance for rehabilitation – no metaphysics, no hierarchy of values exists. Every gesture is an empty pose, and a smile is merely a physical nervous tic, a hopeless attempt to express non-existent emotions.

In the Captivity of the Mask

This analogy might be culturally distant, yet in Mary Harron’s film, I continuously hear echoes of Witold Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke. Ideologically, these two works are unexpectedly coherent. Both cultural texts comment on postmodern society, often relying on exaggeration and caricature of their social lives. In American Psycho, just like in the Polish writer’s book, the characters are trapped in an atheistic world devoid of metaphysics. They are left with only empty, unreflective rituals and daily customs, and their faces have turned into “masks,” behind which our true identity is deeply hidden. The concept of human existence promoted by Witold Gombrowicz in Ferdydurke seems present not only in the adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s book but also in many other works of contemporary art. It is based on the constant processing of cultural motifs, continuous play with audience habits, denial of traditional values, and most importantly, turning towards form. The narrator of Ferdydurke reflects on this, and it is worth giving him the final word, as his conclusion seems to be taken straight from Patrick Bateman’s mouth.

The longer I weave, examine, and digest, the more clearly I see that the main, fundamental torment is, as it seems to me, simply the torment of bad form, bad exterieur, or in other words, the torment of phrases, grimaces, expressions, masks – yes, this is the source, the spring, the beginning from which harmoniously flow all the other sufferings, frenzies, and torments without exception. But perhaps it would be better to say that the main, fundamental torment is nothing else but the suffering born from the limitation by another person, from the fact that we suffocate and choke in the narrow, tight, rigid idea of us by another person.