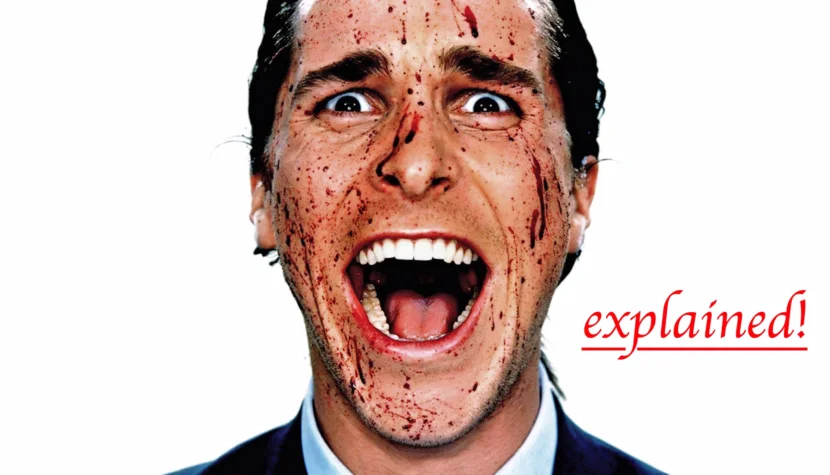

AMERICAN PSYCHO. Controversial Shocker Explained

Significant films for this genre emerged during this time, including Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs, David Fincher’s Seven, Rob Reiner’s Misery, Martin Scorsese’s remake of Cape Fear, and Philip Noyce’s The Bone Collector.

Is American Pycho a thriller?

The common feature of these films is the construction of the screenplay, which relies on similar psychological portrayals of the characters and narrative structure. We always revolve around the same types of characters. The crimes are always committed by someone exceptional in some way: piercingly intelligent, endowed with above-average physical strength, psychologically unstable, and aggressive. Of course, all these films are also indebted to Alfred Hitchcock‘s Psycho, paradigmatic for the genre. In each of these films, the criminal intrigue is clearly resolved. We receive a logical explanation for all the offenses, murders, or crimes. The depicted world returns to the disturbed safe state. This is not, of course, a radical rule. For instance, in The Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal Lecter ultimately remains at large. However, we still feel a sense of relief – the most dangerous person, Buffalo Bill, is eliminated: he will no longer pose a threat. The aforementioned titles are also pure in genre: they clearly separate the perpetrators from the victims, not venturing into horror, social drama, or comedy. They rather deal with an exceptional case difficult to generalize. American Psycho

Against this backdrop, American Psycho directed by Mary Harron stands out decidedly. This film evades known conventions despite using many elements typical of thrillers. The director, in her narration, balances on the edge of reality and an unreal, dreamlike nightmare, sometimes maintained in the gore cinema style. It’s impossible to guess which sequences were imagined by Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) and which actually took place. This deceptive, subjective narration resembles that used by Martin Scorsese in *The King of Comedy*. Harron plays a game with the viewer: the imagination of the main character strongly interferes with the course of events, making everything seem unclear and uncertain. Therefore, American Psycho can also be interpreted as a study of schizophrenia – an attempt to convey the perspective of a person suffering from the condition. However, it’s with this character that we must identify in the film; we see the world through his eyes. Harron often tries to emotionally blackmail the viewer. We don’t want Patrick Bateman to be caught. Before his life begins to fall apart and the character descends into madness, we identify with him. Even more so, we envy him a little. Bateman leads an attractive lifestyle: he is surrounded by luxury, constantly in the company of beautiful women, can afford everything, is always elegantly dressed, has a perfect physique, and a spacious modern apartment.

Mary Harron, however, does not only tell the story of an individual’s drama. American Psycho can also be interpreted as a treatise on the downfall of a generation – the American stock traders of the late 80s and early 90s, colloquially known as yuppies. This group consists of young people from wealthy families who have graduated from top economic schools – hedonists manifesting false political correctness. The director devotes a lot of screen time to show the daily routine of these people. Harron simultaneously does not have the ambition, like Oliver Stone, to comment on the economic strategies used by stock market players. American Psycho is not an analysis of the market’s condition but of the enslaved mind of an individual – a not fully aware victim of soulless capitalism.

An essential role in building the psychological construction of the character is played by detail – not only introduced through the image (such as a business card). Bateman meticulously confesses to the viewer what fluids, shampoos, suit brands, or ties he uses. Through first-person narration, Harron introduces us into the mind of a psychopath. We begin to pay attention to the same details as he does. This is not balanced by the perspective of another rational person, someone from the outside. Only occasionally can Jean (Chloe Sevigny) be considered an objective and reliable witness. However, it is Patrick Bateman who completely dominates the entire space, creates it, and defines its boundaries. Everything is filtered and processed through the gaze of the main character, who cannot control himself.

The threat we deal with in American Psycho has a rather atypical source for a thriller. Usually, in the history of this genre, the murderer comes from the outside, does not identify with the rest of the citizens – lives alone on the outskirts of cities, does not lead any social life – is practically always a loner and introvert. Additionally, his actions are clearly motivated. In American Psycho, however, it is the social group itself that generates the threat. Its most representative, fully assimilated, and subordinated member rebels. Patrick Bateman’s behavior is a reaction to a seemingly orderly and safe social system. This change forces us not to view the adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s book as another conventional realization of the genre’s principles and structures. American Psycho primarily tells the story of an individual’s crisis and a destroyed generation: it is a social drama that sometimes escapes into the realms of action and shock cinema. However, not to introduce us to a criminal intrigue – as it is a secondary, incidental thread – but to convey the main character’s state of mind. Bateman’s visions serve as expressions of his fears, revealing his hidden nature.

American Psycho: Gentleman and Barbarian

Patrick Bateman is an ambiguous character. We meet him as a gentleman, a pedant, a connoisseur of men’s fashion trends, a sensitive music lover living in a sterile, modern apartment. In one of the first scenes, Bateman additionally delivers a monologue, whose political correctness strikes with its falsehood. For instance: racial segregation. The nuclear arms race. Terrorism and hunger. We must feed the homeless and give them shelter. Combat racial discrimination and strive for civil rights and gender equality. We must return…to traditional moral values. But above all, we must consolidate society…and combat materialism in youth.

The main character, when in company, wears the mask of an educated and cultured person. He behaves as the environment demands, conforms, and believes in the prevailing norms. However, this is just a facade because Bateman embodies all the pathologies of modernity. In his environment, we meet only white Americans. He is ostentatiously disgusted by poverty, dirt, the homeless, and the unemployed, and women are merely toys to satisfy his sexual needs. He has only the need for rebellion, breaking the apparent order. He is a prisoner of his hidden “self.” Over time, his second personality begins to dominate, increasingly intruding into his daily life. It is also important to note that Bateman, committing subsequent crimes, is not driven by revenge, a sense of injustice, nor is he a banal sadist, nor does he kill people according to some ritual. He falls into an unidentified trance. Patrick Bateman, of course, feels that he is losing control over himself. However, he does not want to stop this process. He is still present as an off-screen narrator, trying to be beside the viewer, continually conducting self-analysis. As he says: I have all the characteristics of a human being: body, blood, skin, hair. But I have no clear feelings, except for lust and disgust. Something terrible is happening to me. I don’t know why. Bloodlust from nightmarish dreams has taken over my life. A murderous instinct, on the verge of madness. The mask of normality will soon fall off.

The theme of the mask is not only introduced on a metaphorical level. In the second sequence of the film, Patrick precisely describes how he takes care of his body. At one point, he places an ice mask over his eyes. Later, he spreads ointment all over his face – removing it, he says: But that’s not me. This entire scene unfolds in front of a mirror, emphasizing the dichotomous nature of the main character. Bateman dresses every morning to play, pretend, blend into the environment. Such an interpretation is also suggested by Bret Easton Ellis. One of the quotes opening his book comes from Judith Martin’s guide *Miss Manners*: “All civilization is based on manners, which we maintain to avoid tearing each other’s eyes out…In a civilized world, there must be certain restrictions. If we followed our impulses, we would have killed each other long ago.”

The famous scene of American Psycho where stockbrokers compare their business cards depicts the conflict between these two orders. Underneath the manners and gentlemanly eloquence lie vast reservoirs of animal aggression. Drawing out each business card resembles presenting a weapon, as if it were the measure of one’s personality, defining character and position. It seems the stock market players at the table are competing for leadership in a pack. The business card – this fraction of the presented world – becomes the main character’s obsession. Patrick Bateman starts sweating, his hands tremble. He appears cornered. The confrontation between the business card holders seems physical. This scene is much more than just a humorous, sophisticated caricature. The background sound, reminiscent of a snake’s hiss, gives the scene dramatic weight and intensity. Close-ups of faces with shallow depth of field make the exaggerated oppression of the situation even more palpable.