Horror movies TOO TERRIFYING to watch them twice

It’s not about the amount of spilled blood and disemboweled bodies of innocent victims, although these elements are crucial in the world depicted in horrors and some thrillers. What matters is the narrative approach that delves so deeply into the viewer’s emotions that they experience fear and repulsion simultaneously and decide that enduring a screening of such visual horror just once is enough to remember what they never want to watch again. I’ve already written about such films a few times. I’ll only mention A Serbian Film, House of 1000 Corpses, The Human Centipede, or the psychopathic thriller, or if one prefers, the psychological horror Funny Games. The world presented in these productions triggers a radical opposition, fear, disgust, and the desire to escape in the viewer’s psyche, rather than just a mild thrill of emotions. Below are a few more or less known productions that are so frightening and simultaneously realistic that one should be familiar with them, yet a single viewing is enough to leave a mark on more sensitive personalities.

Cannibal Holocaust (1980), dir. Ruggero Deodato

Naively, I thought that one viewing would be enough to understand Deodato’s message. However, it took three times to fully comprehend it. Of course, the film fulfills the criteria of its theme. After a single viewing, any person with a moderately stable level of personality and sensitivity to violence should experience profound fear, opposition, and disgust. Through an experiment with portraying violence, the director attempts to tell us something more. I want to debunk the myth that Western culture has embraced, like a dog gnawing on a chicken bone that a clever Master forbade it from foolishly devouring throughout his short and senseless life. Senseless, because it’s incomprehensible in terms of culture, illiterate, and unintelligible. The myth that Deodato challenged is the belief that the propensity to harm others depends on the level of culture, writing and reading skills, general technical civilization, and cognitive abilities. We function in a world no less mythologized than that of the ancient Greeks. We carry out the biological program of species reproduction, and to make it more effective, we created our own culture and used it to rise above the animal world. However, our myths are no longer based on a supernaturally constructed reality, although we sometimes believe they are. They are genetically programmed, culturally shaped visions of what a contemporary human should be in order to survive as a society. One God, one wife, and a stack of bodies rotting in the basement, all belonging to victims whose lives nobody personally took. The system did that, and that’s justification enough. If that’s the case, why are the stacks in the basement and not prominently displayed in the living room?

Related:

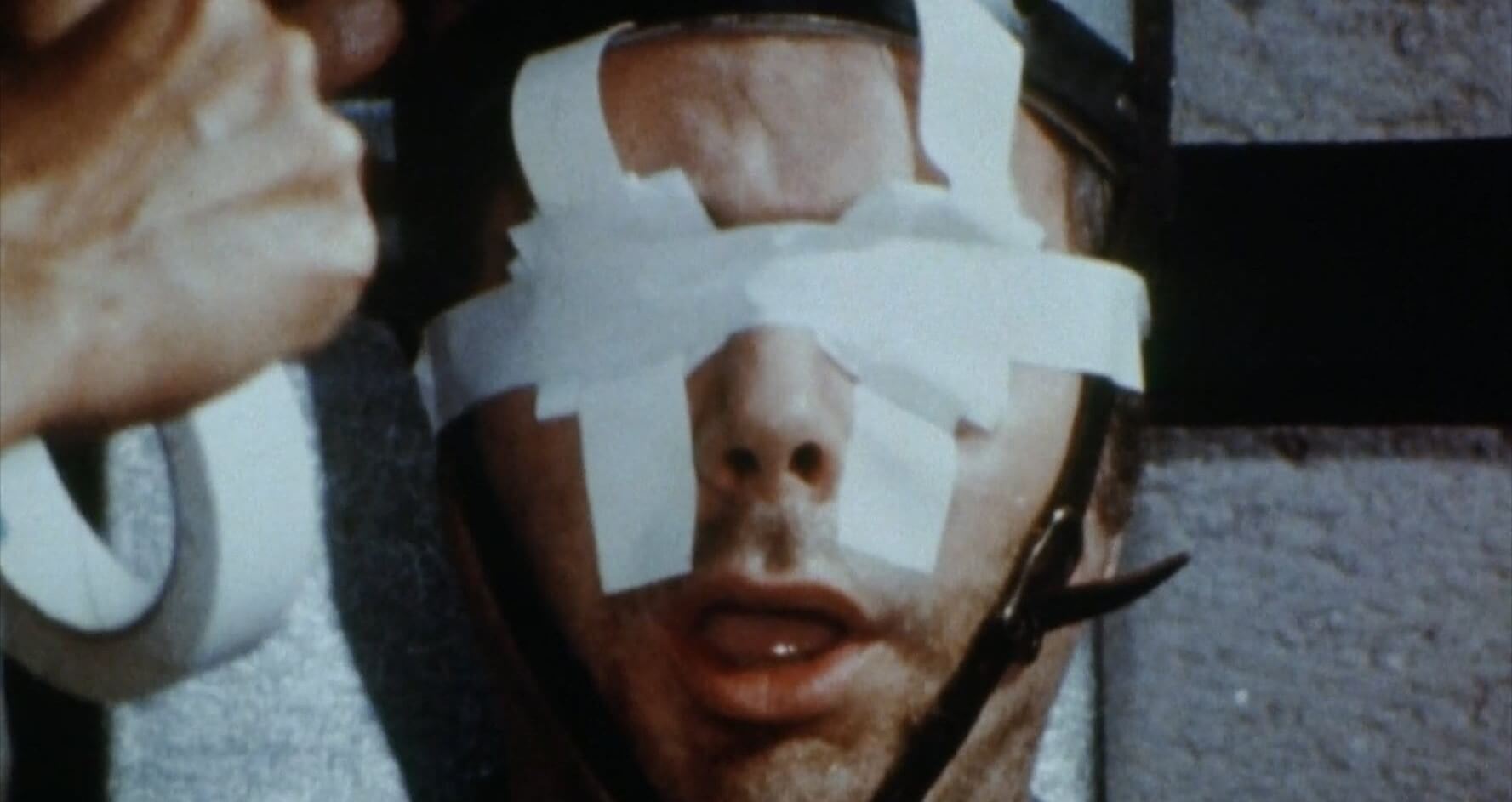

Schramm (1993), dir. Jörg Buttgereit

I am apprehensive about such productions due to the moral vulnerability of viewers and how easily they succumb to their fantasies about idols, regardless of how vile and deviant the antagonists are. Surprisingly, toxic fandoms easily form around such films, propagating a psychopathic admiration for characters like murderers and their actions. The same applies to Lothar Schramm, the protagonist of another controversial horror film by Jörg Buttgereit. A few years ago, I wrote about his necrosexual production titled Nekromantik. Schramm is no less controversial, perhaps even more so due to the blend of nearly pseudo-documentary, reconstructive narrative character with dreamlike attempts at interpreting and understanding the killer’s behavior. Blood, suspense, repulsive camera shots of intimate body parts, physiological processes, and Lothar’s hygienic actions like cleaning a synthetic vagina with his own semen—all of these mundane activities of a lonely man are spiced up with brutal murders and what goes on inside the protagonist’s mind. One small relief for the viewer is the film’s duration. They only have to endure for 65 minutes. Afterwards, they can cover themselves with a blanket and try to sleep, provided they don’t want to purge their fear in the form of vomiting first.

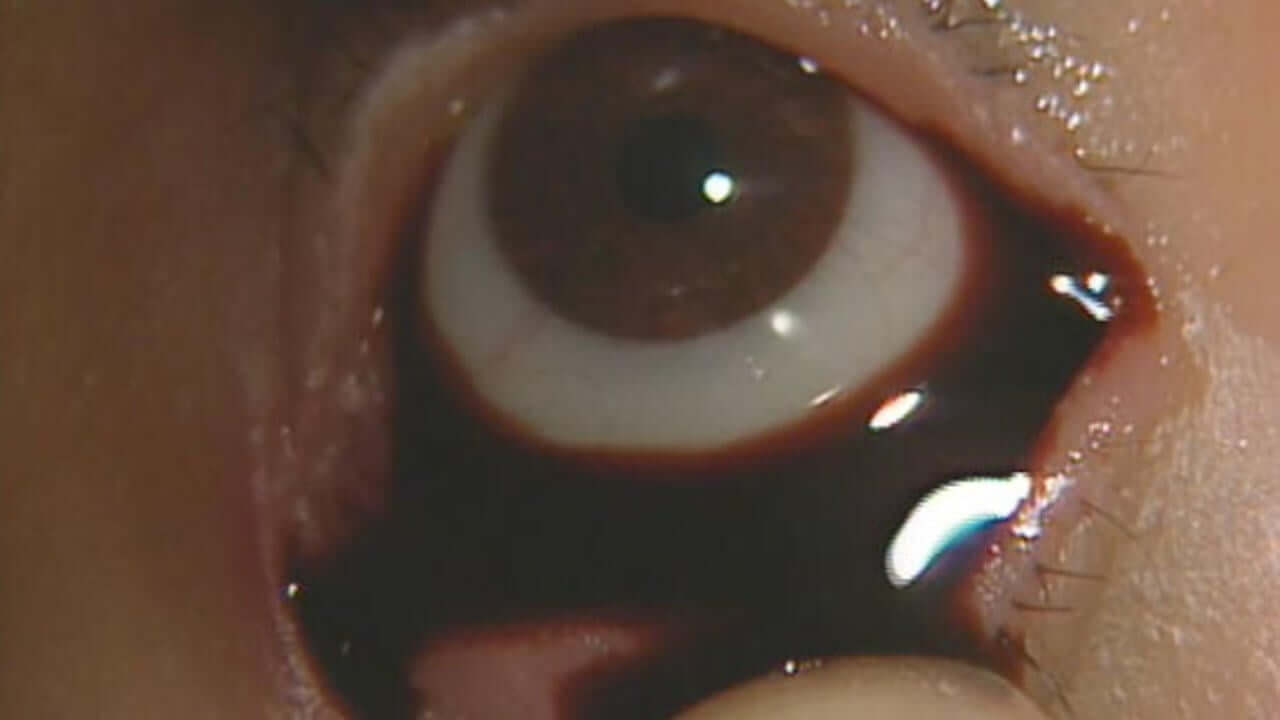

Guinea Pig: Devil's Experiment (1985), dir. Satoru Ogura

What is most terrifying here? In Guinea Pig, the tormentors sadistically inflict senseless suffering on the victim, who paradoxically reacts with incredible humility and resignation. The woman accepts her pain and, above all, the inevitable approach of death. She endures it with a bowed head and often closed eyes. She doesn’t want to look and witness the senselessness of the idea of suffering divided into parts, each labeled as a type of torture. Perhaps precisely because of her humility, the tormentors decide to destroy her eyes. Hideshi Hino wants to emphasize with his film that some viewers will see only senseless violence in Guinea Pig, as human nature inherently contains the duality of perceiving truth. On one hand, a person can successfully see it with their eyes, yet simultaneously fail to interpret and convey it to others because they lack knowledge about the world, even about what they are currently perceiving. Therefore, the eyes must be destroyed, gouged out, and in this act, the victim must experience as much pain as possible as punishment. Have I adequately encouraged you to watch it? Just one viewing of the process of body-killing torture is enough to learn to see…

Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), dir. Shin’ya Tsukamoto

What fascinates me is the combination of seemingly contradictory themes in Japanese cinema into a cohesive whole that makes sense, even though in the case of Tetsuo, a single exposure to the subject is entirely sufficient. If any of you will have the willingness to venture into a viewing of Tsukamoto’s work, you might try a thought experiment: imagine a horrifying image of a steel phallus drilling through a woman’s vagina, penetrating her abdominal cavity, in color. The absence of color in the film saves the viewer from shutting off the screening, because the creators’ intention is for someone to endure until the end. Tetsuo is so surrealistic that categorizing it within the horror genre might seem stretched to some, but it is indeed horror, specifically a subgenre known as Japanese gore with elements of torture porn. The atmosphere of the production is constricting, almost suffocating. The transforming body of the main character terrifies, disgusts, taps deep into our instinct to flee from the unnatural, from that which is connected to death and suffering. The mechanical penis is just one element of violence, which, when combined, culminates in a true, technodemonic apocalypse.

The Last House on the Left (1972), dir. Wes Craven

I want to make it clear right away that for entirely different reasons, I have no desire to revisit this horror from the era of what’s known as early Craven, where experimentation with form took precedence over aesthetically and technically organized cinema. Fortunately, that changed over time, but not yet in 1972, when The Last House on the Left was released. However, I understand people for whom this film is terrifying and who won’t want to encounter it again. Its horrifying nature lies in its simulated pseudo-documentary realism. There is no hope in the depicted world. Instead, there is ruthless violence perpetrated by humans, by everyone. Victims become perpetrators, and revenge renders the meaning of existence utterly void. And all this fear is present in the narrative despite the questionable color of the blood pouring from the victims. How is that possible?

Raw (2016), dir. Julia Ducournau

The scene involving scratching and removing damaged skin foreshadows a lot, although it appears relatively late. As the film progresses, it becomes more intriguing, intense, increasingly claustrophobic, and more extreme. There might be those mischievous enough to recommend the film to vegetarians. Particularly significant is the scene in which the main character, a devoted vegetarian, steals a hamburger and stuffs it into the pocket of her apron. Then comes the time for consuming raw meat. If I recall correctly, it’s chicken breast. Justine’s entry into cannibalism begins with her eating her own hair. The process of extracting the hair from her throat is incredibly disgusting. Subsequent stages involve her sister’s finger, leading up to a human brain. Can you already guess what the culmination of the neophyte vegetarian’s love for meat will be? Studying veterinary medicine and being a vegetarian is a commitment. Of course, I’m writing this sarcastically and with a wink, and as for the film itself, I won’t revisit it unless absolutely necessary. I don’t see anything in it that would provide enjoyment, let alone any entertainment value. Raw is more of a taxing and repulsive experience for me, in an incomprehensible style that’s bizarre.

Ringu (1998), dir. Hideo Nakata

In most horror films, ghosts aren’t frightening to me anymore, or perhaps over the years of watching them, I’ve lost the ability to be scared by supernatural entities. The issue might be that too often these supernatural beings are woven into predictable storylines. Horror creators don’t always make an effort to cleverly integrate them into the plot, allowing the viewer to first fear their own imagination and then what the director and special effects team have planned. And still, at least for me, ghosts will always be less terrifying as elements of horror than suitably portrayed, distorted humans. In the well-known to the public film Ringu by Hideo Nakata, the ghost isn’t as crucial to the scare factor. What matters is the process of unveiling the face of evil.

Under the Shadow (2016), dir. Babak Anvari

Similarly to the title described above, Under the Shadow doesn’t rely on blood, guts, or monsters, although there is a scene under the bed that makes your heart race faster, and it’s based on a very simple use of a certain anatomical motif, just on a larger scale. However, what’s most terrifying is something else. The use of war, a purely human creation with supernatural elements where the latter are only a complement to the real and physical fear experienced by the main characters – a mother and child. You only need to watch the film once to understand what is the primary carrier of evil, personal rather than imagined. You also only need to watch the film once to realize that you won’t want to experience those emotions again. I mean scenes like the one at the table. I recommend and do not recommend at the same time, as best as I could.

Similarly to the title described above, Under the Shadow doesn’t rely on blood, guts, or monsters, although there is a scene under the bed that makes your heart race faster, and it’s based on a very simple use of a certain anatomical motif, just on a larger scale. However, what’s most terrifying is something else. The use of war, a purely human creation with supernatural elements where the latter are only a complement to the real and physical fear experienced by the main characters – a mother and child. You only need to watch the film once to understand what is the primary carrier of evil, personal rather than imagined. You also only need to watch the film once to realize that you won’t want to experience those emotions again. I mean scenes like the one at the table. I recommend and do not recommend at the same time, as best as I could.

Kuso (2017), dir. Flying Lotus

I wonder if “horror” is the correct genre term here. However, I included this film in the list because it undoubtedly evokes both unease and disgust. The feeling of fear should also arise in the viewer due to the disturbing images of deformities and other bodily monstrosities. However, what will dominate the viewer’s mind is primarily the unease about what image will be presented to them closer to the end. One could say that Kuso, one of the most disgusting films in the history of cinema, works in a delayed manner. It’s a stream of consciousness that carries with it surprisingly much, considering it’s a surrealist production – those dreams that we know and secretly hide, and won’t even betray them when they torture us. Undoubtedly a controversial vision, perhaps too frightening for some viewers, or even too personal to repeat the viewing with a calm heart and a clear conscience.

Faces of Death (1978), dir. John Alan Schwartz

The series has already become surrounded by myths. In my neighborhood video rental store, these titles were placed even higher than porn films. The cheaply made covers, however, were more tempting than the big silicone breasts of nameless actresses from German productions. And those legends I heard since childhood mainly revolved around one belief: that these tapes contained recordings of “real death” scenes. How does that sound? “Real death” is a concept we flee from with all our might, including from films that depict it. The fact that we love action movies where bodies pile up doesn’t contradict our fear of the end of life, because in such productions, death is shown in a way that we’re aware of its unreality. We use this fictionalized vision to camouflage our own fear of “real death.” But the latter will undoubtedly touch us, while the movie version is unlikely to happen in that form. That’s why Faces of Death is so controversial, as it stylizes itself as true to life. We watch it once and feel the stifling atmosphere of morgues, the screams of accident victims, the lonely moans of those dying in agony. Unless we suffer from thanatophilia, one viewing is more than enough.