House of 1000 Corpses. Rob Zombie’s mad horror explained

Primarily known as a musician, singer, and lyricist – that’s how he is best recognized, although from his own words, he would happily send the entire music scene to hell just to be able to freely make films.

Rob Zombie

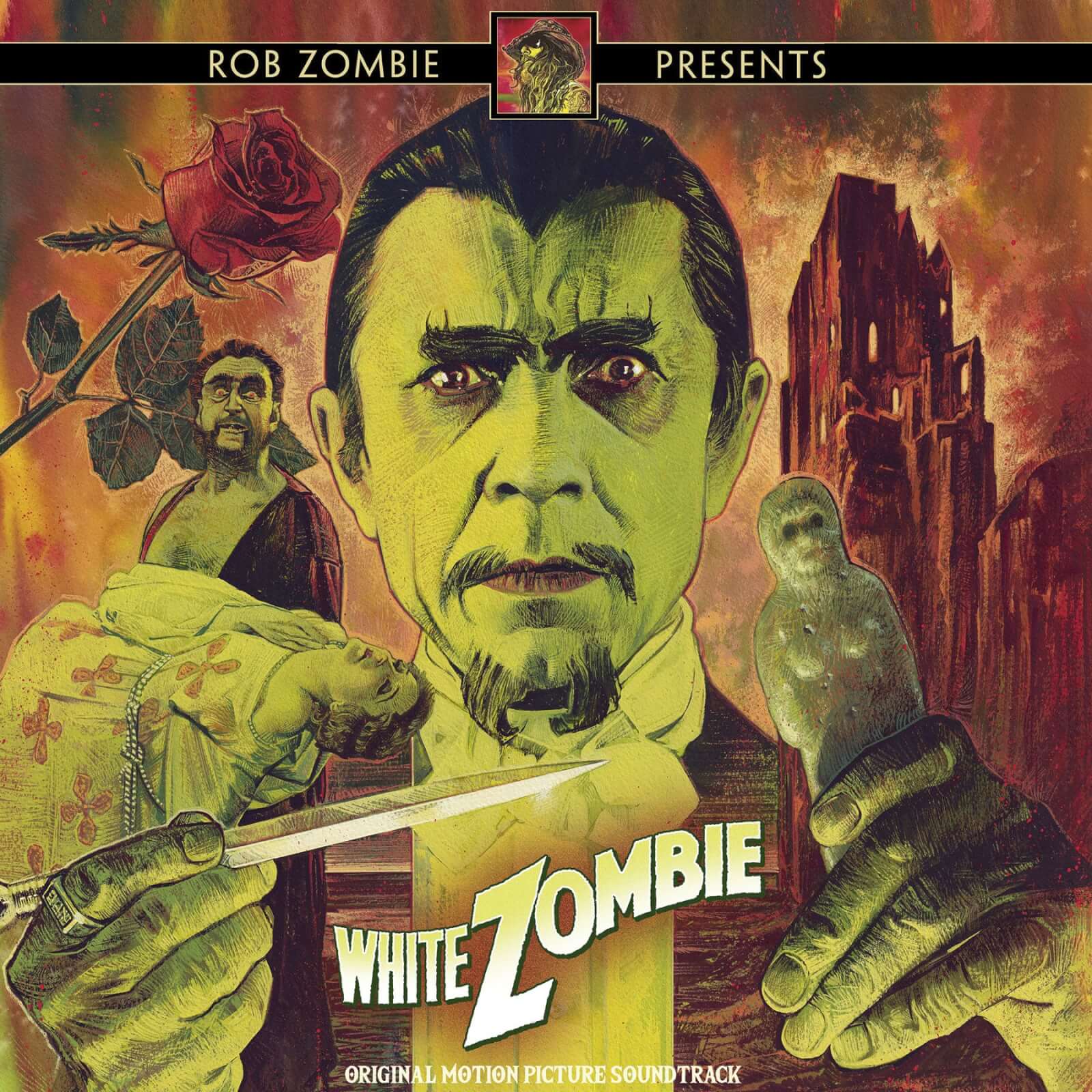

Believe it or not. So far, he can boast a few films, each of which left behind a bright trail of scandal. Rob emerged from the shadows in 1984 when he formed a band called White Zombie with his friend Sean Yseult, taking the name from a 1932 film starring Bela Lugosi (a reference that later proved to be very characteristic of Rob). The band drew inspiration from heavy metal giants on one side and punk outsiders on the other, and like any group searching for their own identity, they were safely classified as part of the underground movement. They achieved a stronger sound when former Accused member, the enigmatic guitarist known as J., officially recorded as Jay Noel Yuenger, joined the group. Eventually, White Zombie established itself as a heavy metal band with industrial elements. In their quest for a theatrical persona akin to Kiss and Alice Cooper, they settled on a style drawn from old horror films – evident in their costumes, makeup, music videos, and promotional methods. White Zombie achieved great success, performing together for thirteen years until Rob decided to pursue a solo career in 1996. The official reason for the band’s breakup was “burnout.”

Rob’s interests are not limited, as mentioned before, to the music market. He is also a producer, comic book creator, illustrator, and screenwriter. He directed most of his music videos and personally designed the abundance of tattoos covering his body. He even tried his hand as a TV presenter. In short, he has countless interests. However, his passion for filmmaking holds a special place in his heart. It dates back to his earliest years and has its roots in his first on-screen fascinations, which remain with him to this day. Rob Zombie is a true film enthusiast, especially a connoisseur and admirer of all kinds, genres, and levels of horror films. It is a level of adoration similar to what Quentin Tarantino has for comics and 70s B-movies. For Quentin, this particular passion transformed into Pulp Fiction. For Rob, it took the form of House of 1000 Corpses.

Compared to his debut film, Pulp Fiction seems like a mild tale spun by sophisticated gentlemen. When making his debut movie, Zombie seemingly adopted a pedal-to-the-metal formula. He never lets up for a moment, but most importantly, he excels at it. The film already caused controversy due to the personality of the creator himself. Covered in tattoos and openly expressing admiration for Charles Manson, it gave more delicate individuals the impression of encountering a new face of the Antichrist. The film’s release into distribution did not improve the situation, but if anything, made it worse. Universal, who was initially supposed to handle the distribution, withdrew with horror. After all, what kind of mind could conceive such a vision? It must be the creation of an insane, heretical, satanic, and generally speaking, crazy imagination. Better to wash their hands of it and not worry about the intimidating implications of the “NC-17” barrier…

House of 1000 Corpses is a culmination of Rob Zombie’s previous experiences – all his actions, more or less artistic, led directly to the creation of such a film. All his passions were centralized in it. However, this debut fascinates not only for that reason. On one hand, it’s a synthesis of various motifs and film inspirations – mainly related to horror, but not limited to it – from individual props to entire sequences. By bringing them all together, Zombie demonstrates his excellent understanding of the horror genre as a whole, and furthermore, he shows his ability to play with cinema without setting any limitations such as “appropriate” or “inappropriate”, “fits” or “doesn’t fit”. The process of uncovering these references is enthralling.

On the other hand, the most chilling aspect is the realization that the roots of this film are not solely in celluloid fiction, and what may initially be classified as a sick, completely deranged vision indicative of a serious mental imbalance of the director actually has a solid basis in facts. Unfortunately. There is nothing in Rob Zombie’s film that hasn’t been invented by some other, truly disturbed mind at some point. What the director has done is gather a multitude of detached elements into one, in the form of a saturated pill, adding a surrealistic setting reminiscent of a nightmarish dream. From these individual elements emerges something akin to a synthesis – a narrative of infamous crimes woven into a whole.

As if that weren’t enough, for the purpose of realizing his idea, Zombie adopts the perspective of a madman – one who considers the delusions of his sick imagination as revealed truths. The line between fantasy and reality becomes increasingly blurred. Rational arguments, any signs of sanity, are absent. Despite ourselves, we become drawn into the world of the criminal Firefly family and, in a way, adopt their point of view, observing how it will unfold, all the while completely thrown off course by the overall lightness of the atmosphere, which complements the whole with a taste of absurdity. Without this, without the formula of grotesque that reduces everything to some reasonable level of acceptability, it wouldn’t be possible to withstand such a concentration. And if someone considers this formula as further proof of Rob Zombie’s mental distortion, let them try to imagine the same film, but made with deadly seriousness. It is only thanks to this humorous lightness, seemingly incongruent with the on-screen vision, that we can maintain a distance and occasionally take a deeper breath. The maneuver is perfectly placed and entirely logical.

Now is the right moment to delve more deeply into the twisted, saturated, and vivid universe of Rob Zombie and seek the underlying logic in his vision, which, contrary to all appearances, can be found.

Related:

Nomenclature

The names of several characters are directly taken from five comedies of the Marx Brothers. Captain Jeffrey T. Spaulding is seen in Animal Crackers (1930), Professor Quincy Adams Wagstaff originates from Horse Feathers (1932), Rufus T. Firefly – from Duck Soup (1933), Otis B. Driftwood is a character from A Night at the Opera (1935), and Dr. Hugo Z. Hackenbush can be found in A Day at the Races (1937). All of the above characters are originally portrayed by Groucho Marx. Additionally, in Animal Crackers, Chico Marx plays the character of Signor Emanuel Ravelli – and this name is also adapted for House of 1000 Corpses.

Museum of Monsters and Madmen

The Museum of Monsters and Madmen from the first sequence of the film pays homage to the classic Freaks (1932) directed by Tod Browning. After the film’s premiere, outraged critics called it “degenerate,” and the director himself was pushed to the sidelines and practically bid farewell to his career. For the audience of that time, the cast composed of authentic members of the Freak Show, bound by strong passions and experiencing dramas of love, jealousy, and hatred, was unacceptable. On the screen, we see the same “freaks” that populate Captain Spaulding’s Museum of Monsters. Dwarfs, bearded women, people without hands and legs, severely deformed individuals, a man with two faces, or a lizard man – such a gallery of oddities, symbolically kitschy tourist attraction made of rubber and plastic in Rob Zombie’s film, is terrifyingly real in Browning’s movie.

It is not surprising that such a portrayal was shocking for the viewers accustomed to comfortable perception of “freaks” as nature’s curiosities devoid of souls – and suddenly, they realized that besides their physical deformities, these people were no different from themselves. Freaks was banned shortly after its premiere for over thirty years. The actual production itself was a horror, as healthy and mutilated crew members treated each other with disgust and hostility. Myrna Loy, a candidate for the role of Olga Baclanova, rejected the offer, considering the script offensive. Nowadays, Freaks is regarded as a classic, and according to some critics, it is even considered the best horror film in the history of cinema.

Clown costume

The peculiar clown outfit worn by Captain Spaulding, regardless of the circumstances, has a rich tradition in horror history. From the cult classic Killer Clowns from Outer Space (1988), which permanently discouraged a whole generation of the 1980s from finding circus clowns friendly, to Poltergeist (1982), IT (1990), and even the comic book-inspired Spawn (1997) – clowns, instead of being entertaining, began to be associated more persistently with something entirely opposite. Perhaps it’s because there is something unnatural in the clown persona – makeup expressing emotions opposite to the facial expression suggests ambiguity, insincerity, and masking the truth, akin to deception. On the same principle, fear is the emotion precisely opposite to laughter (although “tears” would be more obvious – but there is, after all, such a thing as tears of joy!).

A clown luring victims into a trap using their apparent harmlessness and funny appearance is not just a movie creation. John Wayne Gacy, one of the most notorious serial killers in history, also used such a disguise (hence, the media gave him the nickname Killer Clown). In his circus persona, he performed shows for children while looking for potential victims among them. Under the floorboards of his home, the police found the remains of 27 boys, and he eventually confessed to 33 murders. He was sentenced to death, and it was carried out in 1994 (incidentally, he spent 14 years on death row). His last words were “Kiss my ass.” How can one maintain that movies are controversial when, in the real world, a criminal safely hidden behind the guise of a clown can operate for years without any hindrance?

Aleister Crowley

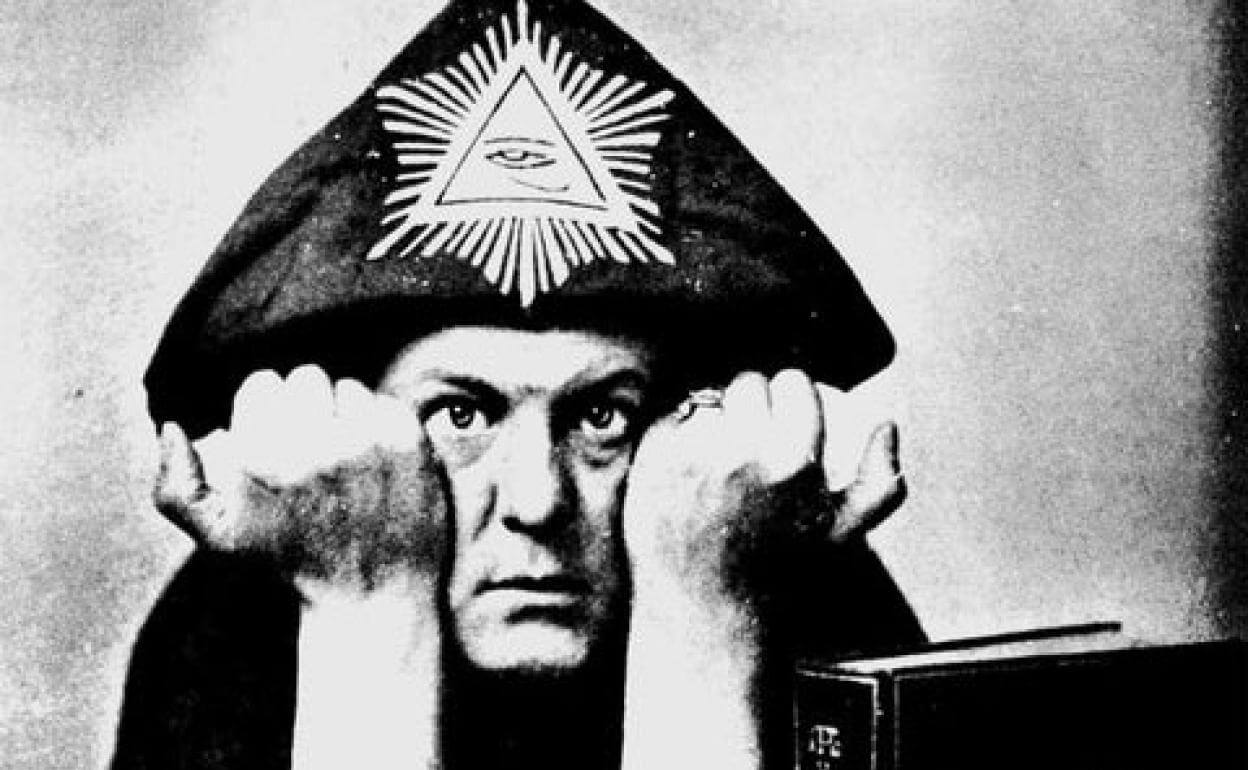

Behind Captain Spaulding’s back, on the wall in the depth of the bar, reproductions of Aleister Crowley’s paintings can be seen. Crowley, a British occultist and mystic, was the creator of the philosophy called Thelema, and the author of works such as The Book of the Law (which he claimed to have written under the guidance of a being named Aiwass). He prophesied a new Aeon in human history, with its ruler being the Egyptian god Horus.

Extraordinary visions and mysterious events accompanied Crowley throughout his life. He remains a fascinating figure and a true icon for occultists to this day. Hundreds of stories and even more rumors circulate about him. Crowley, who passed away in 1947, has become more of a symbol than a historical figure. It can be said that his legend has surpassed his actual work.

The reference to Crowley in Rob Zombie’s film – actually, two references, as in one scene of the movie, a slowed-down tape plays a fragment of a poem written by the mystic titled The Poet (bury me in a nameless grave) – has led some to believe that Zombie is a follower of Satanism. Aleister Crowley, who referred to himself as the “Great Beast” and considered himself to be the embodiment of the Beast from the Book of Revelation, is often mistakenly associated with being a worshipper of the devil or even the spiritual mentor of the Church of Satan. In reality, the foundation of his philosophy was entirely different: he rejected all Christian beliefs as backward and superstitious, and he saw the Beast as a force that would overthrow outdated laws and lead humanity toward a new, better future. Therefore, the argument suggesting that Rob is a Satanist is not entirely accurate – moreover, he has repeatedly denied in interviews that he worships evil. He rather considers himself a sort of agnostic (“someone up there probably exists, but whether it’s God…I don’t know”). This is another example of how easily opinions can be formulated based on appearances.

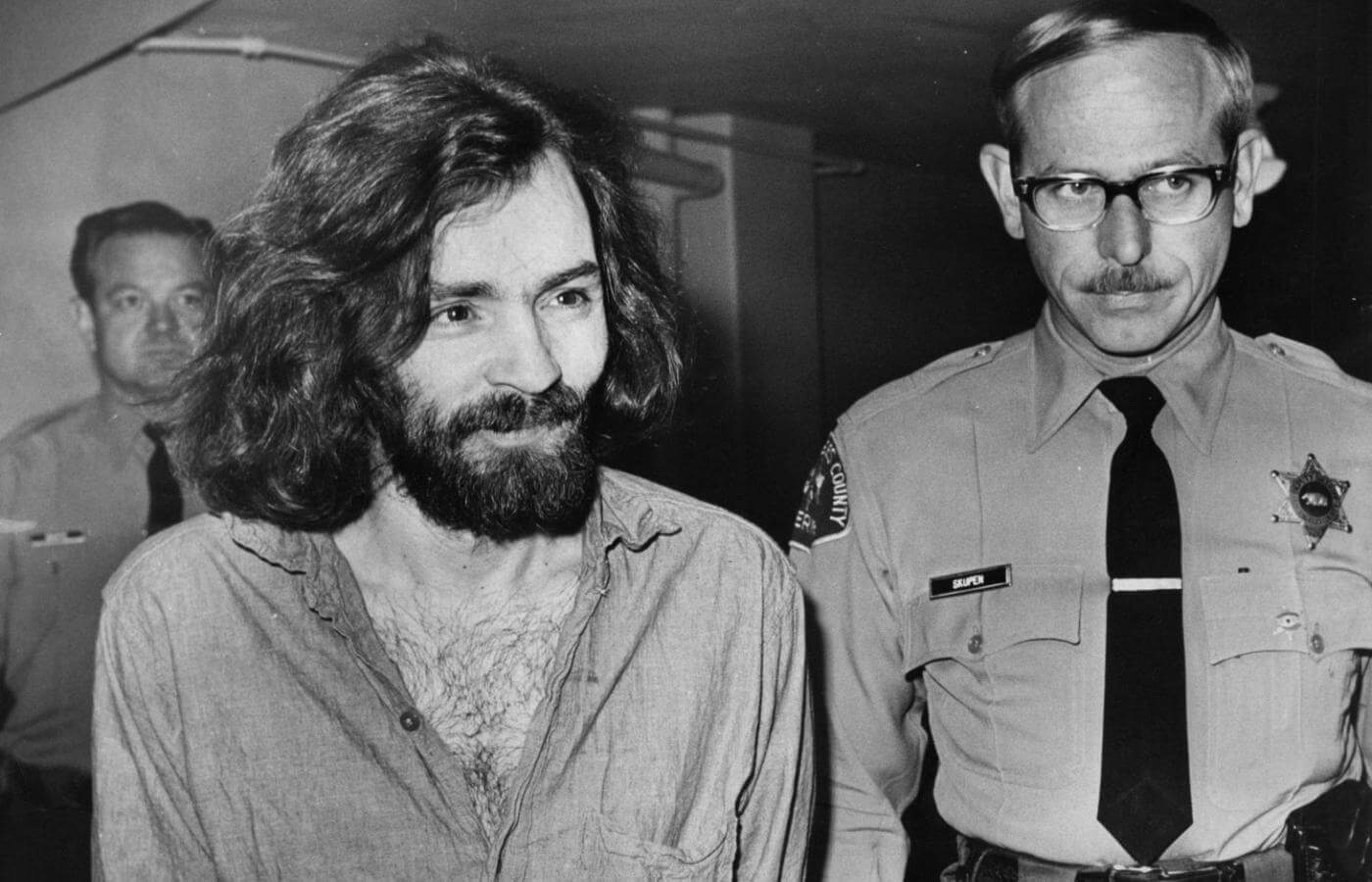

Charles Manson

The introduction of the characters who will soon become victims of the murderous Firefly family is accompanied by a mention of a person whom Zombie has never hidden his admiration for Charles Manson. Specifically, the dialogue refers to members of Manson’s “Family” who were convicted of eight murders, including the killing of Roman Polanski’s wife, Sharon Tate, and her unborn child. Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Leslie van Houten are considered attractive candidates for a date by our unfortunate protagonists. However, that is the extent of Manson’s mention in the film – once again, Zombie could have gone too far, but he refrains from doing so.

The genesis of the plot

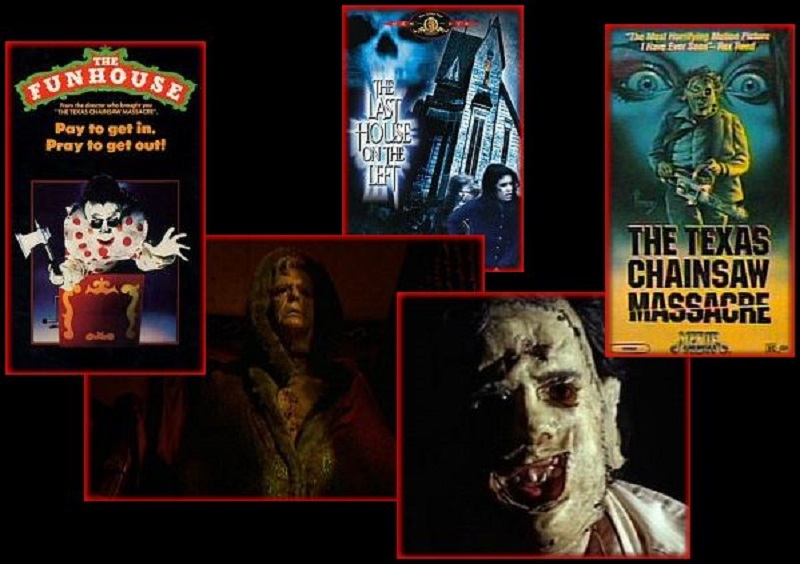

The fates of the four young protagonists are references to several different films. First is Funhouse (1981), a film by Tobe Hooper about a group of teenagers who decide to spend the night in a funhouse and become targets for a psychopath wearing a Frankenstein mask. Another inspiration is The Last House on the Left (1972), Wes Craven’s directorial debut, which provided Rob with some ideas regarding torture methods used by the eerie Firefly family. However, the biggest inspiration came from another film by Tobe Hooper, The Texas ChainSaw Massacre (1972). Elements borrowed from Hooper’s classic include a meal stop at a gas station, a hitchhiker (or, as in Zombie’s version, a female hitchhiker), a deceitful car stop, and a gloomy house inhabited by a psychopathic family led by Leatherface/Dr. Satan.

The Texas ChainSaw Massacre is loosely based on the life of Ed Gein, who also served as the inspiration for Norman Bates in Psycho and Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs. Obsessed with women, Gein wanted to become a woman at any cost. Hence, he went on grave-robbing expeditions to obtain human skin for his costume. He killed at least two people, and there may have been more victims, but it was never proven.

Gein was not a cannibal (unlike Leatherface’s family), but Albert Fish was. Pictures of both Gein and Fish can be seen during the “terror show” at Captain Spaulding’s Museum of Monsters and Madmen – these are authentic documents, including a peculiar X-ray of Fish’s lumbar area, providing evidence of the original use he found for tailor’s needles. Since Dr. Satan is presented third after Gein and Fish, one can infer the nature of his character to some extent.

Psychosurgery and the rest

Treatment of psychiatric illnesses through brain surgery is the idea of a certain Antonio Egas Moniz, known as the “father of psychosurgery” and a Nobel Prize laureate. Moniz developed a system for alleviating depression, delusions, schizophrenia, and even alcoholism by cutting the nerve connections between the frontal lobes of the brain. Patients undergoing such surgery became docile and mild. The fact that they lost a sense of continuity of their own “self” and the ability for rational thinking and feeling was apparently considered an insignificant side effect.

Moniz performed the first such operation in 1936, causing great excitement in the scientific world. In the 1940s, these procedures were performed in large numbers. Prefrontal lobotomy, or leukotomy, was often considered a cheaper alternative to long-term treatment, so it was used without much restraint.

If the thought of a madman attempting such an operation (as envisioned by Dr. Satan) sends shivers down someone’s spine, what can be said about the esteemed guru of neurosurgery, the respected and highly decorated Dr. Walter Freeman, who routinely maimed his patients, performing lobotomies using an ice pick introduced through a hole in the skull made with a hammer for trepanation? When he caused the death of one of his patients using this method in 1965, he was deprived of the right to practice medicine. In the 1960s, the method was condemned as “barbaric,” but before that happened, over 50,000 people in the United States alone were deprived of their will and personality through lobotomies. Patients included individuals with mental disorders, homosexuals, hyperactive children, and political opponents.

A similar kind of lobotomy was carried out by Jeffrey Dahmer, perhaps the most repulsive killer in the history of criminology, earning him the nickname “The Milwaukee Cannibal.” His method involved drilling a hole into the drug-addled victim’s skull and slowly pouring acid solution into it. Dahmer was driven by an obsessive desire for absolute power and control over his helpless prisoner. If he had been born a few decades earlier, he might have had a chance to become a psycho surgeon, but since he came into the world too late, he was left with the career of a psychopath.

Horror hospital

At the end of House of 1000 Corpses we see something resembling an underground hospital and prison at the same time, filled with mutilated people subjected to various medical experiments. Everything is filmed at a frenetic pace and resembles a nightmarish dream filled with disjointed images in vivid colors. These sequences can indeed be considered the strongest or, if you prefer, the “most disturbing.”

Before we condemn Rob Zombie for his unhealthy visions, it is worth recalling the case of Madame Delphine LaLaurie and her spouse. Before the revelation of their secret shook New Orleans in 1834, they carried out their atrocities without hindrance while enjoying respect and sympathy among the local community. Madame Delphine hosted prestigious parties, and receiving an invitation was considered an honor. It was during one of these parties that a fire broke out. Firefighters, called to extinguish the fire, became curious about the horrible odor emanating from one of the rooms on the upper floor. And since they were curious, they decided to investigate.

Madame Delphine did not have an underground hospital, but the fate of the room exposed by the firefighters was somewhat similar. It served as a prison and execution site for several people. Some of them, chained to the walls, were already dead, while others were terrifyingly mutilated. A man was transformed into a woman through crude surgery, a girl with open arm fractures was forced into a narrow cage, and another had her skin flayed while still alive. Everywhere were vessels filled with blood, internal organs, and severed heads. I don’t know if the discoverers of the LaLaurie couple’s secret could ever be the same after witnessing such horrors.

Further investigations led to the discovery of skeletons of other victims who were apparently buried alive. To this day, the exact number of victims of this couple is not known, but it is known that someone like Ted Bundy, who had at least 36 killings to his name, would be far from matching them in this regard. Worse still, the Lalaurie couple escaped justice, and no one ever heard of them again.

Meet the family

Four heroes – two girls and two boys – decide to take a trip to the gallows tree surrounded by urban legend, which they definitely shouldn’t have done. And picking up a hitchhiker along the way was a double mistake.

The idea of cornering chosen victims with the cooperation of a male-female duo has as many references to films as it does to reality, especially in the history of deadly duos: a woman lured the targeted object into the car (like Karla Homolka), or she took on the role of a hitchhiker and ultimately took control of the car, driving the prisoners to where the accomplice awaited (like Judith Neeley did).

The course of the whole situation in Rob Zombie’s film has something of an urban legend atmosphere – represented by the story of “Doctor Satan,” who escaped the gallows, but also the hitchhiker appearing out of nowhere and the ghostly marksman reminiscent of such tales.

The psychopathic family, in whose mercy the unfortunate quartet finds themselves, is bound by blood ties and macabre preferences, but it is also united by a certain love of rituals and the focus around a guru seeking a new path for their philosophy. All of this together brings to mind Charles Manson’s Family, but with a grotesque twist. Halloween, celebrated with special fervor by Mama Firefly, is like a family dinner straight out of a Poe story. To top it all off, there’s the karaoke performance by the provocative and giggly blonde, Baby, who no one would suspect of being a psychopath at that moment – at most, they would think she’s completely brainless.

However, the most interesting moment is when the plot takes a turn. The guests, by no means, are trapped. At any moment, they can leave, and that’s what they do. So, the fact that they end up in the hands of the Firefly family again is solely due to their irresponsible actions, which led to the accident. In truth, they are to blame for what befalls them – after all, they wanted to find out if there was any truth behind the urban legend – exercising their free and voluntary will.

This particular element constitutes one of the fundamental differences between the classic horror template and the mechanisms of actual crimes. In horror films, the characters persistently do what they shouldn’t and, as a consequence, become victims. They visit forbidden places, recite suspicious invocations, disregard warnings – in short, they invite trouble upon themselves. On the other hand, the fundamental trait of a true psychopath is the desire for power and control. Anybody who happens to catch their eye can become their victim – the fact that the person wasn’t seeking trouble doesn’t mean that trouble won’t find them. This convention, inherent in the horror genre, is a nod to the belief that “it will never happen to me,” and that we enjoy being scared – but from the safe comfort of our armchairs.

Creature of the Lagoon, Marilyn and Tarantino

From the moment the Firefly victims fall into their hands again, the number of references begins to multiply. The fate that befalls Bill visually recalls The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), where the protagonist is a creature with a humanoid-fish appearance. The scene where Baby scalps Jerry is a reference to the torture scene in Reservoir Dogs (1992), where Mr. Blonde cuts off the ear of a policeman. Jerry sealed his fate by answering the question about Baby’s favorite actress incorrectly. He guessed it was Marilyn Monroe, likely influenced by her choice of karaoke song: Baby’s rendition of I Wanna Be Loved by You, which Monroe sang in Some Like It Hot. If Jerry had a better frame of mind to gather his thoughts, he might have followed the clue in his tormentor’s nickname and guessed that Bette Davis was the right answer. This is due to What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), where Bette Davis plays the role of a former child star who falls into oblivion as her sister, Blanche, becomes a Hollywood star. When Blanche becomes crippled in a car accident, she ends up under her sister’s care, entirely at Jane’s mercy and caprice – and Jane lets out the hatred and jealousy that tormented her for years.

Hunting in Wonderland

Chained to the bed, Mary is wearing Alice’s dress from Alice in Wonderland. Lewis Carroll’s book has been subject to various interpretations – sexual implications of Alice’s journey, the two Queens as symbols of weak and powerless good and the trap of evil represented by egoism, the tunnel passage as a reference to experiences after death, and many other, more or less sensible ideas.

However, what may interest us here is the fact that Alice in Wonderland has gained a cult status in the pedophilic underworld. Most likely, this element doesn’t suggest another deviation within the Firefly family. It’s more about the world of Wonderland, where the unfortunate Mary finds herself. This is further evident in the cemetery ritual scene, where the victims are dressed in rabbit costumes, and the way to the underground Wonderland leads through a tunnel.

Mary’s desperate attempt to escape ends in failure, but the most significant aspect lies in the disdainful words spoken by Otis: “A running man is no different from a rabbit. Run, rabbit, run!” The dehumanization of the victim, reducing them to the role of an animal, is a common tactic used by most serial killers.

In the history of criminology, one particularly notorious case of extreme dehumanization stands out – that of the Alaskan criminal Robert Hansen. Hansen kidnapped women and then released them, disoriented and terrified, into the deep woods, which he knew like the back of his hand, unlike the victims. He then began a real hunt, as if tracking a rabbit or a deer.

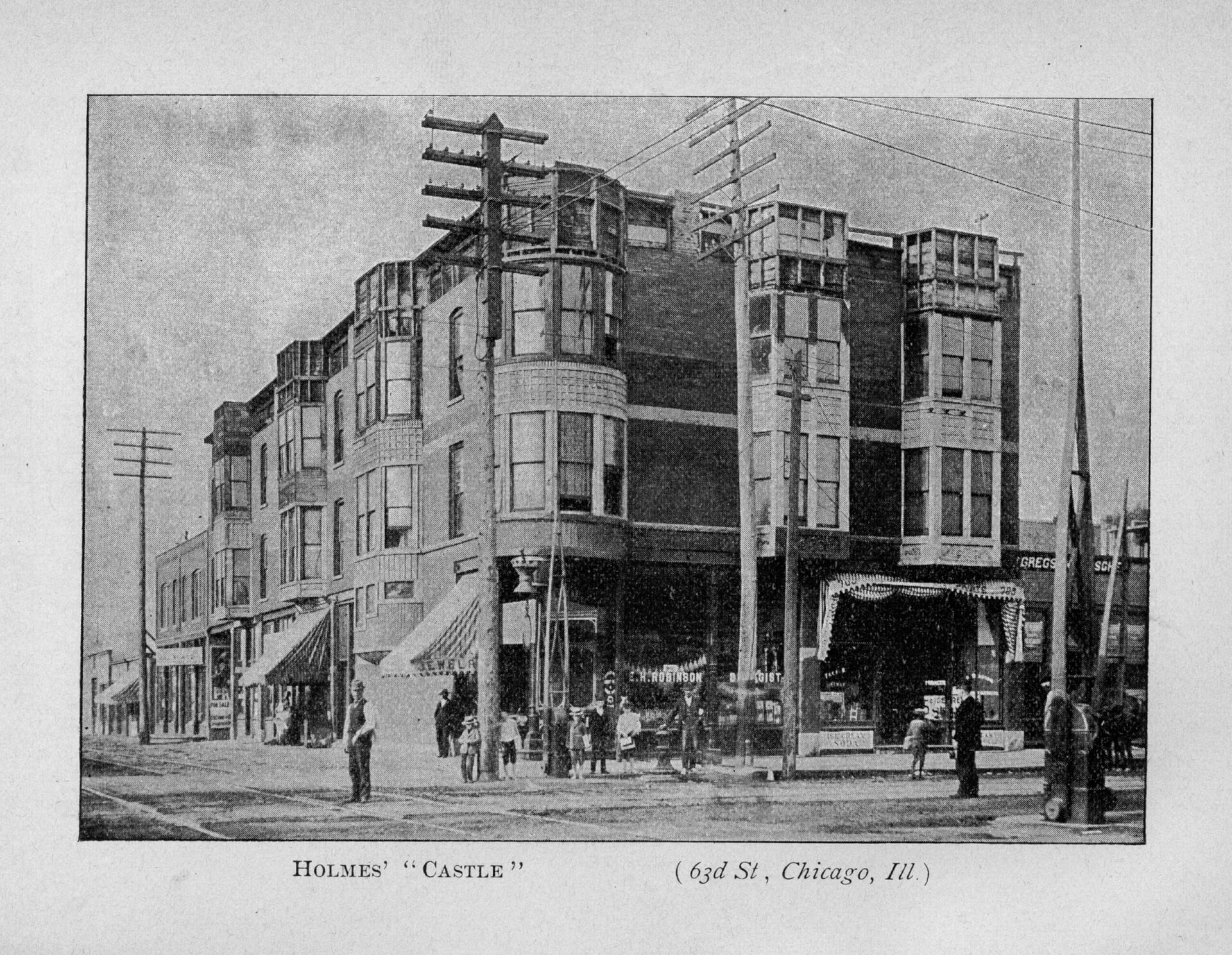

Since we are delving into the surreal underground world where the last surviving heroine, Denise, ends up – a world that evokes a cross between a hospital and a torture chamber – it’s worth mentioning another name. H. H. Holmes earned the reputation as the worst serial killer in American history. He operated at the end of the nineteenth century, and his notoriety is closely associated with the hotel he ran, which later became known as the “Castle of Horrors.” It is estimated that about 150 people, mostly women, met their death there. The underground of the castle consisted of a series of interconnected chambers with secret passages, hidden trapdoors, disguised corridors, and Venetian mirrors. Some of these chambers resembled operating rooms, while others were torture chambers. There was also an authentic gas chamber among them.

Holmes, considering himself a scientist and a pioneer in medicine, conducted extensive research in his “castle,” focusing on psychological aspects (the essence of human fear) as well as physiological experiments (including tissue endurance). When this macabre residence was finally discovered and investigated by the police, there were plans to turn Holmes’s hotel into a museum. Until today, it remains unknown who put an end to these marketing projects, setting fire to the self-proclaimed doctor’s establishment, completely destroying it. One can only assume that someone had some common sense.

Heading for Texas

As I mentioned before, House of 1000 Corpses was heavily inspired by The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The director of Massacre, Tobe Hooper, a native Texan, like many of his compatriots, remains deeply influenced by the local – it would be nice to say “legend,” but unfortunately, it’s pure truth.

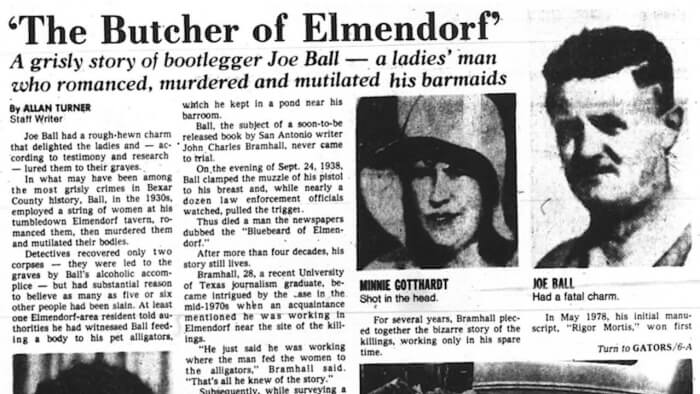

This influence was already evident in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but it found its full reflection in Hooper’s next production, Eaten Alive (1977). Joe Ball, the protagonist of these stories, lived in Texas in the 1930s and ran a local bar, popular not so much for the attractiveness of the service but because of the pets raised by Ball in his home pool – five beautiful alligators. This local attraction drew curious people like a magnet. The more daring ones had the opportunity to participate in gruesome animal feeding shows.

However, what actually constituted the main food for the alligators, the audience was never to find out. The beloved animals were Ball’s unique way of getting rid of inconvenient intruders and women who bored him. This macabre story fits so perfectly into Rob Zombie’s film style that it’s strange the Firefly family doesn’t have a pool with alligators in their garden.

Wayne and the cheerleaders

One of the best scenes in the film, skillfully filmed and perfectly balanced in color, is the scene of Otis carrying out the execution on the policeman. It was directly taken from the movie True Grit (1969) and serves as a reminiscence of the final showdown between Rooster Cogburn (John Wayne – who won an Oscar for this role, the only one in his career) and Ned Pepper (Robert Duvall).

The abduction of cheerleaders and the body in the trunk, as a signal to the police, unequivocally bring to mind the modus operandi of the so-called “Hillside Stranglers,” Angelo Buono and Kenneth Bianchi, who kidnapped girls from university campuses, tortured them in a manner resembling interrogation, and then strangled and abandoned them, either on a hillside or in the car trunk right under the nose of the police, leaving a clear signal for investigators.

In House of 1000 Corpses, besides references and symbolism drawn either from the history of criminology or classic films, there are also authentic shots from several movies, specifically The Old Dark House (1932), The Wolf Man (1941), The House of Frankenstein (1944), Munster, go home (1966); from the series on which the latter was based, The Munsters (1964), and finally, from the first part of the controversial documentary film series Faces of Death (1978), banned in 46 countries.

The Firefly family home is the same one that appeared in the 1982 film The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. House of 1000 Corpses is a tribute from Rob Zombie to the creators of his beloved genre – horror. In addition to Tobe Hooper and Wes Craven, these include Sam Raimi (The Evil Dead, 1981) and John Carpenter (Halloween, 1978). The mask worn by “Baby” comes from Mother’s Day (1980), a film about a group of women who, during a trip to the woods, fall into the hands of a psychopathic mother and her two sons, who specialize in reproducing torture scenes they saw on TV. Baby’s scream, demanding exclusive rights to deal with the escaping Mary, which she ultimately does by telling a macabre tale about a rabbit – the whole sequence is from the obscure horror film The Child (also known as Zombie Child, 1977) – a film guide for children wishing to deal with boring governesses.

Classifying House of 1000 Corpses as a brutal vision lacking both restraint and good taste is highly unfair to this film. Rob Zombie undoubtedly created a new quality for the genre he loves – horror. He did it by paying homage to all his fascinations throughout many years of cinema experience, fully aware that to establish himself in the world of filmmaking, he cannot distance himself from all those who came before him.

This film shows traces of the childlike awe accompanying the first encounters with cinema, the effects of shaping one’s own attitude towards films that have attained cult status, the admiration of the creator for the pioneers of genre solutions, and the path of a rebel shaping his own philosophy. It is evident that the purpose of this film is to shock.

It is shot in a sharp, dynamic, almost music video-like convention, quoting and transgressing, but it does not comment or present any thesis. Nevertheless, everything that appears to be fireworks of senseless violence and conceptless madness to Zombie is a bitingly saturated portrait of human degeneration, which knows no limits in cruelty, perversion, and brutality. Translating this into the language of film is not a crime or evidence of the director’s disturbed mind.

Cinema is an illusion, and the fact that it can draw so much from life while being accused of grotesque excess is only proof that some things are more convenient not to see. The perspective imposed on the viewer by the madman is truly moving, not a horror festival provided by the director. Whatever one may think about the validity of this creation, however one may judge its balance or distance, House of 1000 Corpses undoubtedly creates a new quality – both as an heir to the entire history of horror and as a vividly grotesque systematization of the most memorable cases from the history of criminology.

Perhaps it is Rob Zombie who, for the first time in this form, illustrates how the human mind defends itself against traps that lurk within itself – allowing them to speak but only for the sake of the film.