DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS Explained: The Birth of a Legend

Excessively smooth, painfully pretty, with a diamond sheen and big innocent eyes – vampires in the interpretation of Robert Pattinson and Ian Somerhalder are no longer princes of darkness but pop stars with chiseled abs and romantic inclinations.

These are school celebrities and kings of popularity, who just happen to be undead. There’s really nothing wrong with this, especially if we assume that demand shapes supply – for young female fans, the attractive, pale-faced Pattinson is undoubtedly more appealing than Max Schreck’s long claws or the cold, austere demeanor and pursed lips of aristocratic Bela Lugosi. However, there was someone capable of creating an entirely new definition of vampirism – dangerous, deeply sensual, and physical – long before anyone dreamed of the Twilight series or the vivid frames of Coppola’s Dracula. Someone who embodied dark eroticism without speaking a word on camera. That someone was Christopher Lee in his finest vampiric role – Dracula, Prince of Darkness from 1966.

Specters Rising from the Grave

The myth of the vampire has existed in folklore, especially European, for centuries. However, folk tales about vampires have nothing to do with the pale and refined aristocrat. Greek lamias, bloodsuckers of infants, resembled monstrous hybrids of women and snakes. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, people told terrifying stories of upirs and nelapsi; in Bosnia, rotting lampirs emerging from graves heralded plagues, and the Russian upyr refused even to stay buried. Romania, the cradle of modern vampirism and homeland of the infamous Vlad the Impaler, boasted two kinds of strigoi: vii and mort. The Albanian shtriga was a cunning witch who transformed at night to fly freely and suck the blood of the innocent. German folklore firmly embedded the sinister image of the alp, Latin America feared the powerful tlahuelpuchi, and Japan’s hideous, monkey-like kappa disemboweled its victims.

In India, bloodthirsty traits were not limited to demons like the bhuta but even revered goddesses – Kali defeated the demon Raktabija by draining his veins dry. Even in young American traditions, there is the tale of the Stukeley farming family, where the tragically deceased daughter, Sarah, haunted her siblings and caused their illness until her body was exhumed and burned. Types of vampires differ from one another – some equated with demons, others with witches – but one motif is universal: the thirst for blood, the essence of life, to sustain their wicked existence at the expense of others, preferably the innocent and pure. In folk tradition, vampires were repulsive creatures. They reeked of the grave, were covered in boils and open wounds, and often took the form of unsympathetic animals or decaying corpses. The romantic allure of vampirism emerged only in the 19th century.

The Romantic Parlor Vampire

In 1819, The Vampyre by John Polidori, personal physician to Lord Byron, was published. Polidori had a complex relationship with Byron, both admiring and resenting him, so it’s no surprise that he endowed his protagonist, Lord Ruthven, with typically Byronic traits. Thus began the legend of the melancholic, romantic vampire, perpetuated by Polidori’s successors: James Malcolm Rymer, Sheridan Le Fanu (creator of Carmilla Karnstein, the archetype of all female vampires in literature), and most notably Bram Stoker. Relatively unknown during his lifetime, Stoker created the most iconic work in the history of literary vampirism.

Work on Dracula lasted seven years. The novel’s structure is innovative, composed of fragments of letters, diaries, phonograph recordings, and newspaper articles. Stoker also introduced a set of characters that eventually broke free from the literary original and gained lives of their own: Mina Murray, Lucy Westenra, Renfield, and most famously, the charismatic Abraham Van Helsing. The first on-screen portrayal of Van Helsing was by Edward Van Sloan (in Dracula 1931 and Dracula’s Daughter 1936), but he is most often associated with the interpretation created by the legendary Peter Cushing. Only Anthony Hopkins came close to matching this unparalleled portrayal.

Not all bloodsucking specters from folklore had fangs – yet they are an essential attribute of the modern vampire. It was Christopher Lee who first showcased his predatory teeth up close, adding another element to the new vision of the nosferatu. When a vampire clutches a swooning victim and pierces their neck with long fangs, the erotic undertone of such a scene is undeniable: it evokes both penetration and defloration. Fear and ecstasy merge, celebrating life and death simultaneously. A powerful vampire easily gathers followers: while men are often acolytes, fascinated by the idea of power, might, and immortality, women usually serve as symbols of sexuality – or rather, objects.

Enslaved by the unparalleled pleasure they experience, they are willing to do anything to feel it again, turning the addiction (or vital need) for blood into nothing more than a pretext for pure, unrestrained desire. Vampire stories liberated women sexually long before the cultural revolution – even despite aspects of subjugation or outright slavery. Vampire films grant women the right to feel desire and seek its fulfillment, but simultaneously highlight a medieval belief that a sexually awakened woman is entirely ruled by her passions. For balance, similarly blind obsession grips men enthralled by power and status – men as much as women are subjugated to and dependent on the vampire.

Beware the Vampire on Set

The cinematic vampire legend began in 1922 with the silent German film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror by F.W. Murnau, featuring Count Orlok played by Max Schreck. Altered place names and character names were intended to protect the creators from copyright disputes (only partially successful, as Bram Stoker’s widow won a court order to burn existing copies of the film, fortunately only partially enforced). Count Orlok, predatory, grotesque, and repulsive, is closer to folk legends than Stoker’s vision. In 1931, Tod Browning’s Dracula starring Bela Lugosi brought a completely different vision of the titular vampire. Lugosi’s Dracula is a polished socialite – elegant, refined, yet cold and detached. Some critics, referencing Lugosi’s light, dance-like movements, described his portrayal as balletic. Undoubtedly, Lugosi became a symbol, and Browning’s Dracula a benchmark for subsequent cinematic renditions. However, the birth of a true legend was still to come.

During a career spanning from 1948, Christopher Lee appeared in nearly 300 films. His final role came at age 92, one year before his death. He excelled as villains, aided by his physical attributes alongside undeniable talent. Tall, slim, charismatic, with a magnetic gaze and rugged, masculine beauty, Lee commanded every scene he appeared in. He portrayed Dracula seventeen times, including seven films for Hammer Films. He formed a brilliant on-screen duo with Peter Cushing, playing Van Helsing – a perfectly mannered gentleman with impeccable decorum and Olympic-level fitness. The two were close friends off-screen, enhancing the credibility of their on-screen dynamic.

The Grand Return of the Prince

Lee debuted as Dracula in 1958 under the aegis of Hammer Films. The film marked a turning point for both the studio and Lee’s career, instantly establishing him as an icon of horror cinema. Alongside Peter Cushing, he crafted a duo of mutually fascinated adversaries. Two years later, a sequel, The Brides of Dracula, was released, but fans received it less enthusiastically because the blue-eyed David Peel as Count Meinster was a stark departure from Lee. Christopher Lee’s portrayal of Dracula had so profoundly imprinted itself on audiences that they simply could not accept any alternative vision.

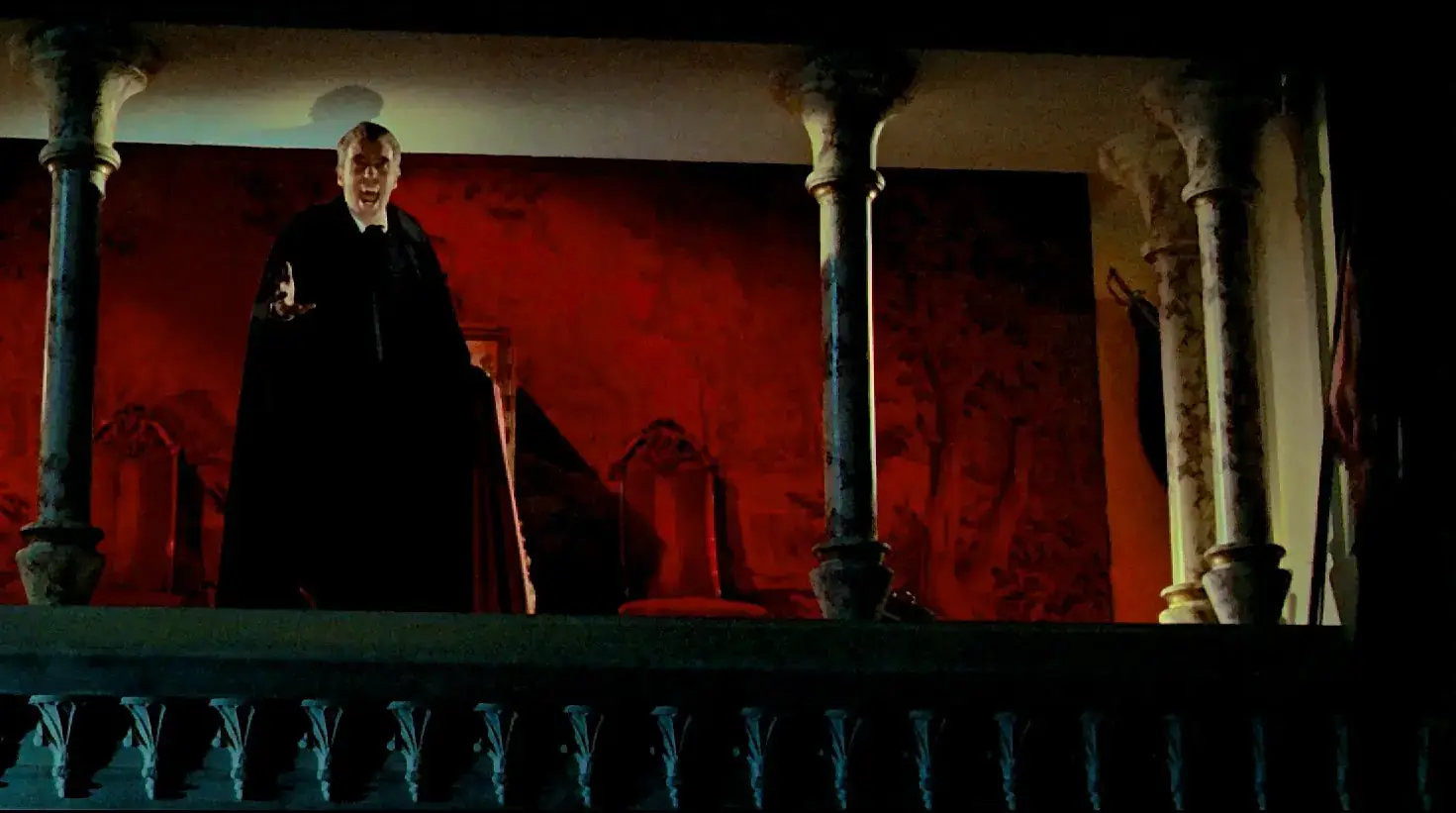

Sensing the audience’s preferences, Hammer Films once again cast Lee in the titular role in Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966). According to rumors, Lee was so displeased with the scripted dialogue that he chose to maintain an enigmatic silence instead. Meanwhile, the scriptwriter insists this is just a cinematic legend, claiming he never wrote any dialogue for Dracula. Regardless of the truth, this decision worked in Lee’s favor. The story of Dracula, Prince of Darkness takes place ten years after the events of the first film. Two couples – brothers Charles and Alan (Francis Matthews and Charles Tingwell) along with their wives, the sweet Diana (Suzan Farmer) and the slightly sharp-tongued Helen (Barbara Shelley) – travel through Eastern Europe. Despite the stern warnings of the enigmatic Father Sandor (Andrew Keir), they head toward Karlsbad. When their coachman refuses to continue after dusk, the four disoriented tourists find themselves unexpectedly at the hospitable castle of Count Dracula, where they are warmly welcomed by his servant, Klove (Philip Latham). Only Helen seems to harbor doubts, while the others eagerly accept the promise of a good meal and a comfortable bed. Helen’s instincts prove correct – the tourists are merely a source of blood for a ritual to resurrect Dracula.

The film struggles from the lack of a strong opponent for Dracula, as neither Matthews nor Keir can match Cushing. Even Dracula himself remains a secondary character, with the story focusing (unfortunately) on the four hapless travelers. Yet, despite limited screen time, Christopher Lee sustains the enduring image of Dracula that would become the blueprint for countless film vampires.

Lee’s Dracula is intensely sensual, athletic, and magnetic, radiating an exotic allure with a touch of decadent charm. At the same time, he is ruthless, brutal, and dangerous. For him, it’s about more than survival through blood – he relishes the hunt. He grows bored with what he has already conquered, especially if it came too easily, and takes clear pleasure in violence. He treats his minions with utter indifference, moving them like pawns on a chessboard. Yet, he remains irresistibly captivating. In the scene where he transforms Helen (discreetly, under the cover of his cape, igniting the viewer’s imagination), one cannot help but notice that she appears not terrified or shocked, but fascinated.

Dracula’s cold treatment of the submissive Helen closely mirrors the dynamic seen years later between Gary Oldman’s Dracula and Lucy. The true targets of his obsession are Diana and Mina – the women he cannot easily conquer. Christopher Lee’s magnetism, transcending even grotesque makeup, marks the beginning of the fascination with vampires as charismatic and attractive men. He is the godfather of Lestat, Edward, and the Salvatore brothers. This version of Dracula focuses entirely on his sensual, physical presence. Themes often explored in vampire stories – loneliness, unfulfilled desires, the curse of eternal life, and the burden of sins – are completely absent here.

The supposed demise of Dracula at the film’s conclusion is rushed and unconvincing, a mere formality. The audience is keenly aware they have just witnessed the birth of a symbol, one whose immortality no one can ever take away.