SCIENCE FICTION movies for INTERSTELLAR fans

This movie is not included in a list, but I mention it here in the header – K-Pax, to give it special attention. Sometimes we may mistakenly associate Interstellar with strictly scientific cinema, and scientific with a lack of emotions. Interstellar is a film about emotions, about their universality, regardless of where you are and in what time of the universe. K-Pax is also a movie about science, but in a much less tangible way, more intuitive, taken ‘on trust.’ That’s why fans of Nolan’s ‘scientific’ approach may appreciate this increasingly forgotten film directed by Iain Softley, with the controversial Kevin Spacey, which has the power to soften hard-headed arguments. And what about the rest of the films? I don’t have to like them all to appreciate them, and even more so, to recommend them to Interstellar fans.

Contact (1997), dir. Robert Zemeckis

First on the list only because I was writing this text when, thanks to the courtesy of a certain cable TV, this production was playing on the television. Fans of Interstellar will find in it basically the same philosophical issues:

Human Relationships: The film examines relationships between people, both in a scientific and personal context. Ellie, as a scientist, must confront biases and bureaucracy in her field. At the same time, her personal relationships with other characters illustrate how difficult it is to establish and maintain relationships in the face of massive discoveries and challenges.

Time and Space: The main character experiences phenomena related to time and space during her contact with an alien civilization, or perhaps visions of that contact, similar to Cooper. These aspects lead us viewers to reflect on the nature of time and space.

The Emergence of Extraterrestrial Intelligence: The question of how society and the world would react to the actual confirmation of the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence is one of the main themes of the film. This issue concerns politics, religion, ethics, and global social changes. People are not prepared for it, even in the face of a great catastrophe. They may be prepared only as selected individuals.

Interpreting Individual Experiences: The heroine experiences an intense encounter with an alien civilization, but the lack of material evidence for this event raises the question of whether what she experienced was real or perhaps a result of her desires, will, needs, and childhood experiences. And Cooper may also have experienced hallucinations. He never went anywhere, or maybe he wasn’t alive for a significant part of the film?

The Limits of Knowledge and Understanding: Human knowledge and cognitive abilities are limited, but that doesn’t mean they are deceiving us. Our ability to understand the cosmos may indeed be constrained by our technologies and cognitive abilities, leading to the question of whether there are limits to our understanding of the universe. The circle closes. So, we entrust understanding to machines, more and more so.

Related:

Children of Men (2006), dir. Alfonso Cuarón

There is something in this film reminiscent of George Orwell’s bleak vision of the future. The author of the novel, P.D. James, must have drawn from 1984, which paid off. Alfonso Cuarón directed a film that is very realistically post-apocalyptic but also fictionally scientific, which will satisfy Interstellar fans, especially due to its dystopian theme. Throughout the movie, there is a constant feeling that the world has either already died or is about to end. In Interstellar, Nolan also creates reality in this way, not only on Earth but also on alien planets.

Linoleum (2022), dir. Colin West

I admire Christopher Nolan’s cinema, but sometimes you need to detox and change the style, as well as the mood, let’s say, the range of emotions offered by a film. Nolan’s cinema, including Interstellar, is usually multi-threaded, hence complex. So, you can detox with easier cinema, but not necessarily. You can find similarly internally twisted productions within science fiction. Linoleum is exactly that – intimate, with a playful approach to science, while still attempting to answer important questions about humanity’s place in the cosmos, or rather, human thinking about the cosmos. Fans of Interstellar will certainly appreciate the peculiar treatment of the issue of time. There will be something to think about after watching, perhaps not as much as after Tenet, but certainly material for discussion is present.

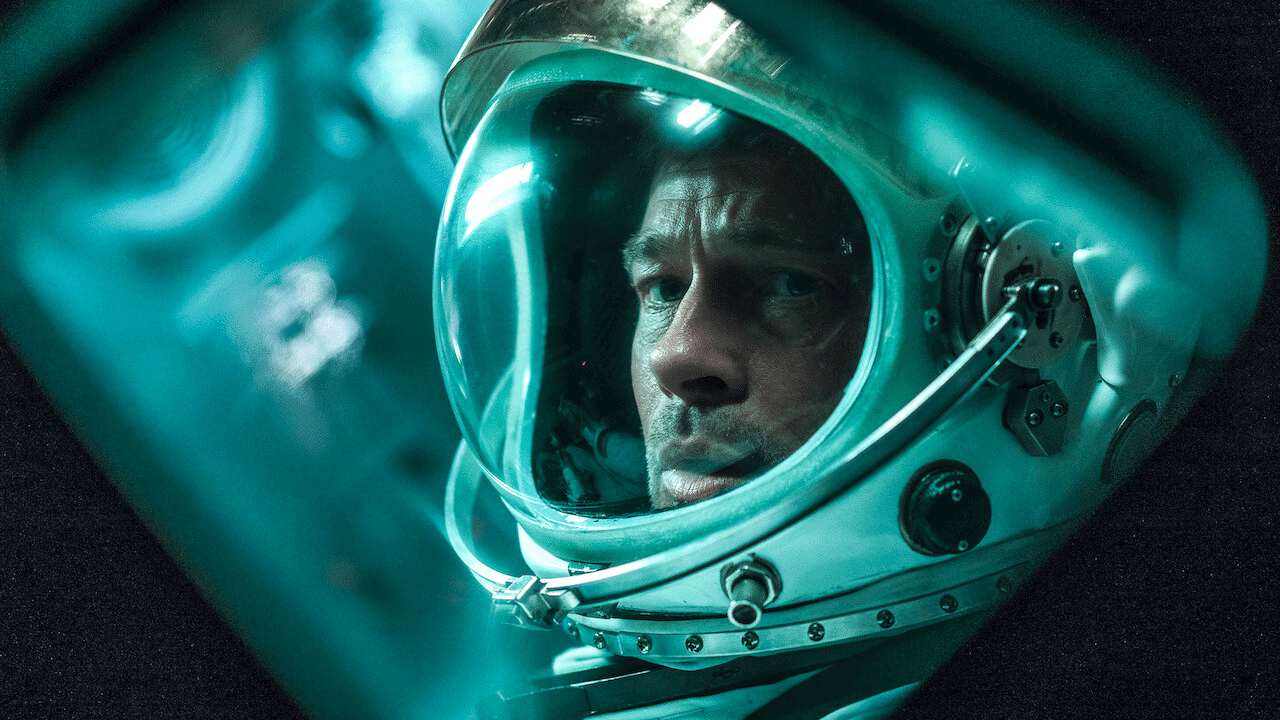

Ad Astra (2019), dir. James Gray

From a retrospective standpoint, I can say that the visual style of this production can still be appreciated today. Its calm narration also somewhat resembles Interstellar. However, when it comes to scientific accuracy, it’s a different story. In the case of Ad Astra, I’m on the negative side, but I have a feeling that the pacing of this story might entice Nolan’s fans. The film does offer reflections, perhaps somewhat shallow, but you can infer depth if you wish. We search far and wide when what is valuable is within arm’s reach. This is a valuable observation, but we act this way because we don’t seek other frames of reference for our value systems. For us, there’s only man and the metaphor of his father, whom he wants to return to because everything else is meaningless without this journey. This theistic anthropocentrism, presented as a positive value, only hides behind a celebration of life and love, but in reality, it feeds our self-satisfaction that we are at the center, the most important because we are created in the image and likeness. Therefore, if we were to find intelligent life forms in space, we would lose this position because we would encounter a different culture, different laws, different gods; we wouldn’t be able to prove any of our reasons, especially the reason for our existence and our former creation. Our life might suddenly seem alarmingly absurd, appearing as a mysterious concoction of ruthless logic working for a trivial purpose – reproduction. Unfortunately, such deep reflection was missing in the film Ad Astra. You can only sense its faint echo. However, it is clearly present in Nolan’s work.

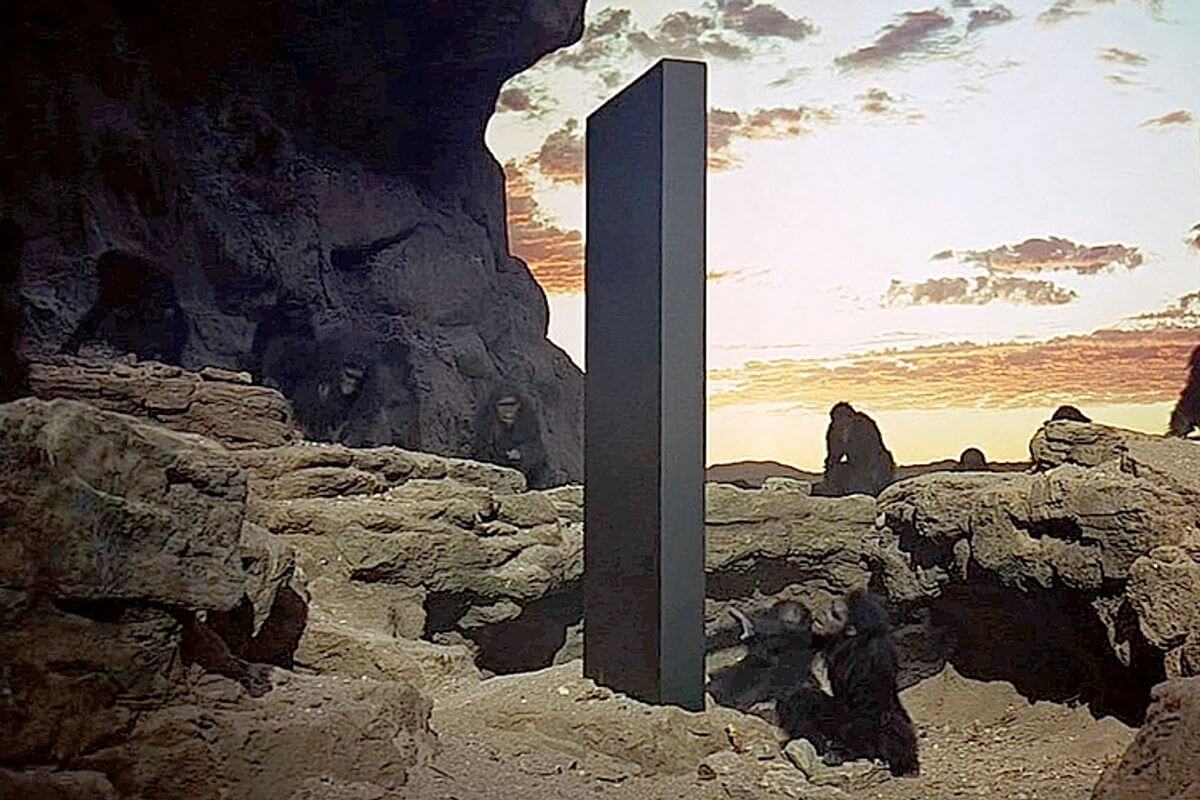

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), dir. Stanley Kubrick

I have no doubt that this is a film for Interstellar fans, but let’s think about it for a moment. This monumental work, by its nature, is much more bombastic than Interstellar. It assumes that human understanding of the cosmos is the only one, even though a wise human being should feel reverence for the vastness of the cosmos. But is this not just feigned humility? It’s clear that humans are always at the center of human interest, but this perspective is quite limited by the type of knowledge. This unwavering belief in truth, or rather, a human vision of it, can lead us to get lost in pathos, in the imagined and presumed value of our existence, even though culture requires us to acknowledge that we mean nothing in the face of the universe.

Arrival (2016), dir. Denis Villeneuve

I remember giving this production a chance for cult status just over two years ago. However, I don’t have that impression today. Viewer and critic ratings are high, but it’s like appreciating perfect craftsmanship that lacks the irrational artistry. Nevertheless, it’s a refined production, precise in narration, with an interesting twist, suspense that doesn’t get boring, and a leisurely pace of the plot, a rhythm that engages and keeps you waiting in suspense for the explanation. It may disappoint some viewers, just like in Nolan’s perfect films, where sometimes the culmination isn’t as good as the journey to discover it.

Bird Box: Barcelona (2023), dir. David Pastor, Àlex Pastor

Bird Box starring Sandra Bullock is an interesting piece of science fiction cinema, with a slightly weaker ending compared to the introduction and development of the story. Fortunately, this is not the case with Interstellar. The ending is complex, raises a lot of doubts about the main character, and even begs for a sequel. However, Christopher Nolan probably won’t make one. Perhaps someone else will, although I fear it would be difficult to create similarly iconic cinema. Bird Box: Barcelona on the other hand, is not a direct sequel. It’s more like a spin-off, supplement, or another film in the same universe, making it an interesting take on the story. The narrative rhythm is generally unhurried, although there are action elements, so fans of apocalyptic themes should be satisfied, although I’m unsure about the ending.

Paradise (2023), dir. Boris Kunz

I gave this film a lot of trust as a European-style science fiction movie, and I wasn’t disappointed. The beginning may not have been dazzling, but then the futuristic layer began to harmonize perfectly with the humanistic layer. The film gained a leisurely pace, leading the viewer deeper into contemplations of ontological nature, much like what Christopher Nolan explored from various angles in Interstellar. Science fiction cinema should ask these questions, dress them in a rational and uplifting atmosphere, yet without an excess of unnecessary emotions. Science fiction cinema should present these questions with a graphic style designed with painterly elegance. And finally, science fiction cinema should tell us stories through the mouths of characters that are not easily repeated in the same words because they escape commonality and stereotypical thinking. You’ll find all of this in Paradise.

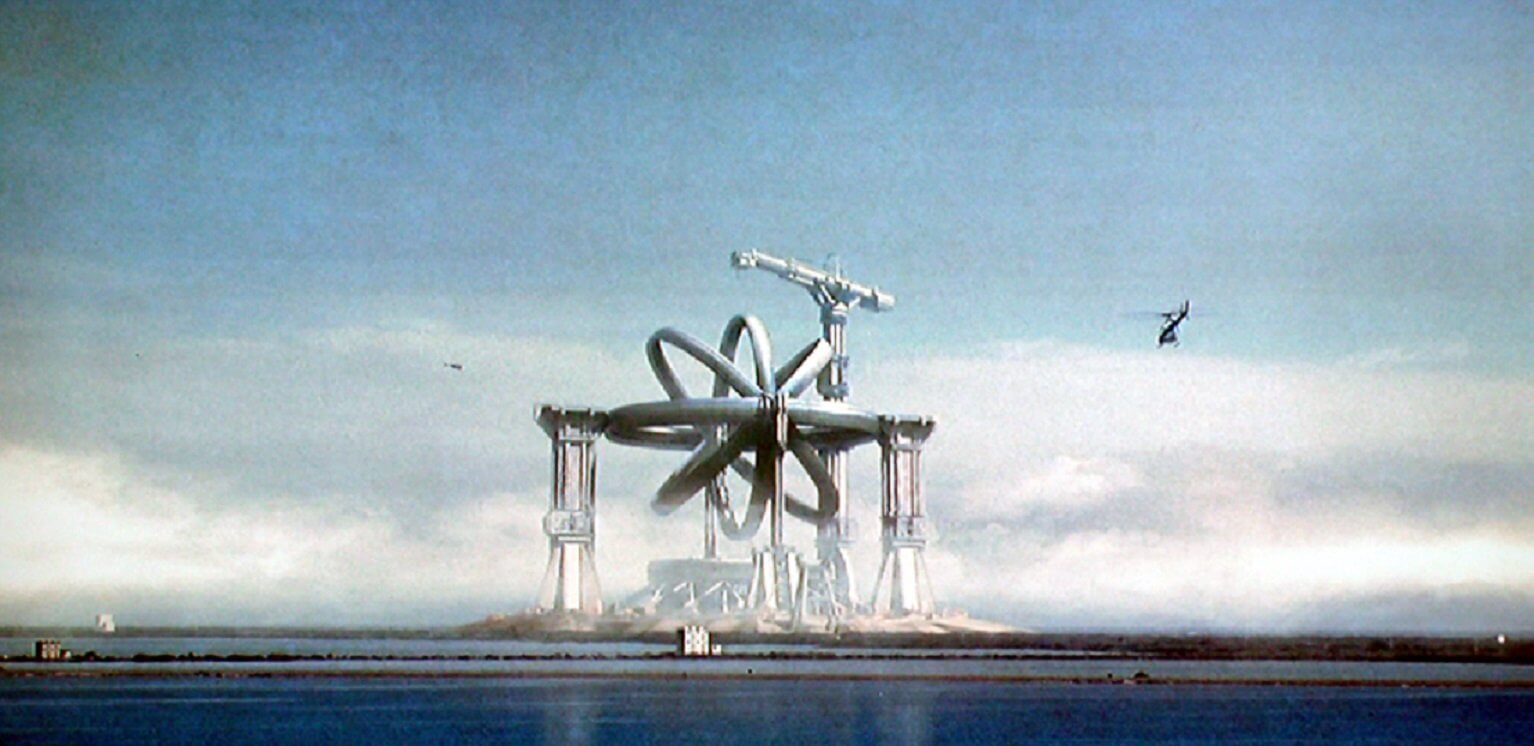

2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984), dir. Peter Hyams

It’s good that they made a sequel. Viewers have a much more digestible story at their disposal compared to Stanley Kubrick’s version. They can enjoy both the interesting visual form and the highly science-fiction storyline. Maybe Christopher Nolan in Interstellar presented events very abstractly, but he didn’t forget about the so-called playability, accessibility, and directing it towards the audience, not just his directorial ambition. So, the sequel directed by Peter Hyams doesn’t offend the original in any way while respecting the audience’s patience and not falling into formal excess.

Howl's Moving Castle (2004), dir. Hayao Miyazaki

A magical tale for the patient, and I assume that fans of Christopher Nolan are patient and not easily discouraged by the narrative. Howl’s Moving Castle is included in this list as an exception due to its rhythm and wisdom in analyzing human life, as well as its advanced symbolism. The animation is syncretic, combining elements of science fiction, steampunk, post-apocalyptic cinema, fantasy, and parable. So, if my assumption is incorrect, and fans of Interstellar are not sensitive to the metaphorical nature of this type of animation, please let me know. For now, I believe that Howl’s Moving Castle will resonate with them.