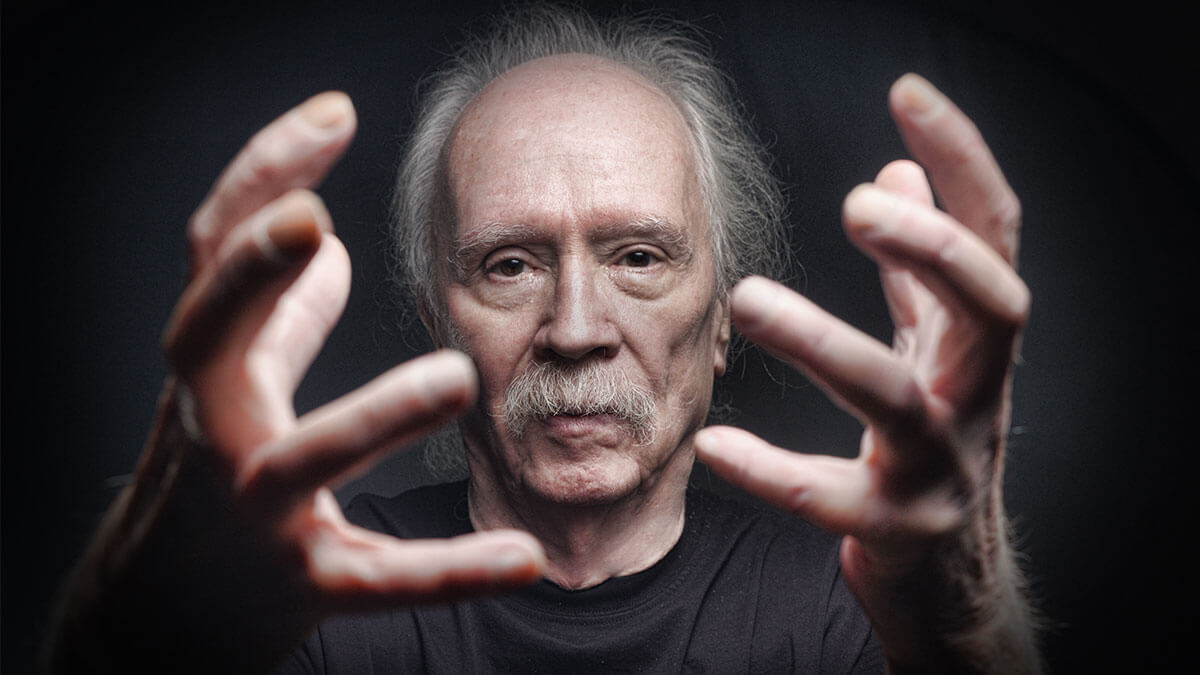

The Apocalypse according to John Carpenter

With the exception of Starman, 1984, the Unknown was a threat in all of these films. It came from space, manifested itself as a ghost in the machine, or sprang from Chinese black magic. Carpenter’s heroes fought to the end. And although they won, their sacrifice was mostly in vain, because the Unknown in the last scene seemed to say I’ll be back. At best, there was a dramatic understatement and suspension of the final solution in a vacuum. Among these nine independent feature films, John Carpenter chose three titles that make up the so-called The Apocalypse Trilogy: The Thing (1982), Prince of Darkness (1987) and In the Mouth of Madness (1995).

Taken individually, these three films have nothing in common. Even from the perspective of John Carpenter’s filmography, they form a rather random sequence of works by an artist who made his films usually when someone came up with an idea and money. Because the career of John Carpenter, as an extremely stylish B-movie director, rarely fit into the artistic timeline typical for such famous artists, planned several steps ahead. Even in the 1970s, Carpenter’s low-budget ideas had a certain production continuity, and their creator had the deciding vote. But after the first unsuccessful flirtation with Universal during the production of The Thing, things changed a bit. From then on, his films were usually followed by proposals from small and larger studios, looking for a guy who would bring an interesting, but low-grossing idea in a well-groomed author’s style to the screen for ridiculously little money. And the financially insecure Carpenter often took what was available.

In spite of this randomness, John Carpenter consistently moved forward in building worlds on the brink of global annihilation. He signaled its foretaste in Escape from New York (1981), throwing Snake Plissken into the Manhattan prison. The plot pulsating with action plus the low budget distracted Carpenter from clearly outlining the epic vision of the end of the world known to us after World War III, added only in the novelization of the script.

Related:

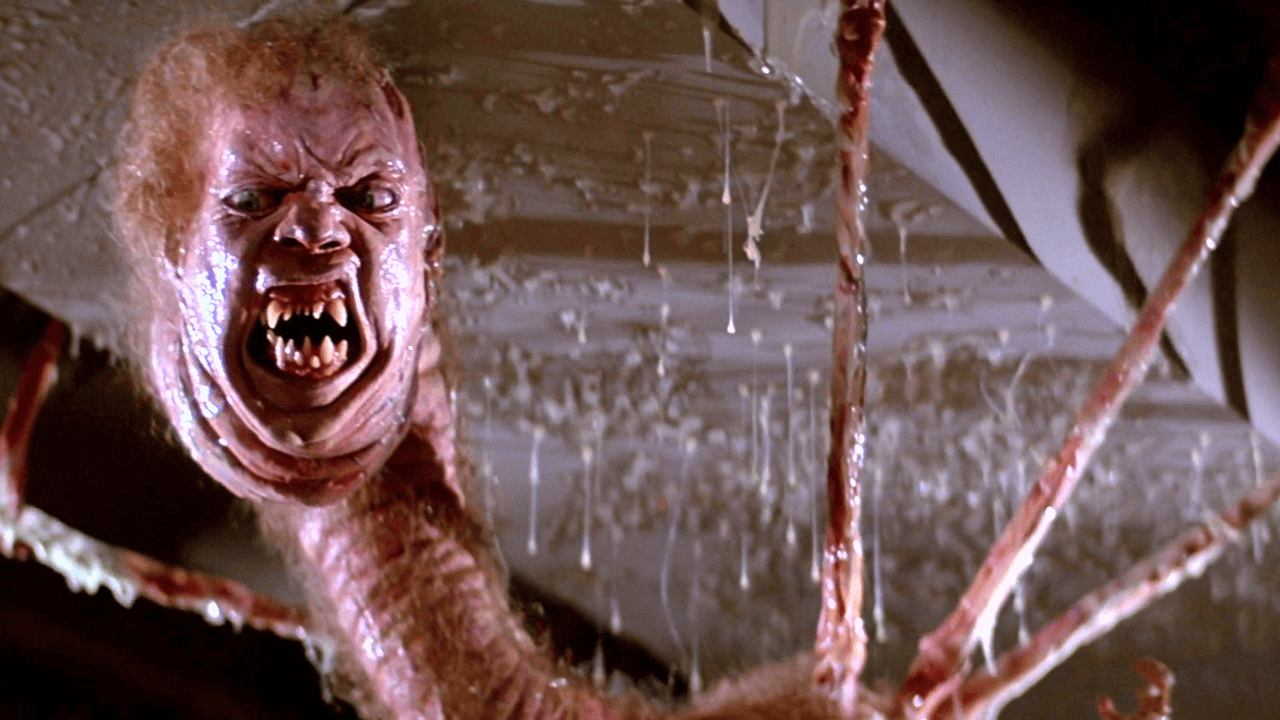

The Thing

The story of the beginning of the end had to go back thousands of years, when an alien ship came from the depths of space and crashed in Antarctica. In the winter of 1982, a team from a Norwegian science station found it. Pulled from the inside of the ship, the alien had an incomprehensible ability to transfer to subsequent biological carriers. A man, a dog, even a stain of blood – it doesn’t matter, survival above all else. The alien in the body of a dog reached the American Antarctic base, and at that moment the action of the film The Thing (1982), perhaps John Carpenter’s greatest work, began. Twelve cornered guys fought with … One would like to write “with a shadow”, but only if we imagine a shadow imperceptibly penetrating our insides and tearing them to an exceptionally picturesque bloody pulp.

John Carpenter’s constant role model was Howard Hawks and his Rio Bravo, from which he drew the starting situation repeated in his subsequent films – the “good guys” bunker in one place, and the hordes of “bad guys” attack from all sides. Attack on Precinct 13 (1976) was, according to many, the most perfect Carpenterian fulfillment of this fictional postulate. In The Mist (1980) this pattern was broken up into several places of action, and in Escape from New York we have its reversal – the “good” Snake enters the closed habitat of the “bad guys” to fight for his own life and that of the abducted US president.

In The Thing, however, character movement restrictions already have several levels. The crew of the station can go outside, but the Antarctic night and freezing cold make the natural escape from “something” completely pointless. It remains warm inside among familiar faces. But it is not known which face hides the carrier assimilated by the alien. The geographic limitation inherent in the realistic Attack on Precinct 13 was intensified in The Thing by the biological limitation. In addition, even the host may not know his tragic fate until “something” takes explosive control over his body. Brought from without, the Unknown has penetrated where man has nowhere to run.

Where’s the apocalypse? Her suspicion is born in a scene of a computer simulation of the spread of a virus among inhabited areas. And the film’s finale, in which the only survivors of the alien pogrom Childs and MacReady lie resigned to their inevitable fate, is closed by Carpenter with an irritating understatement and no final answer to the question of the alien’s death. But if something is going to go wrong, it will. The rest of humanity, absent from the film, is enjoying its last free weekend.

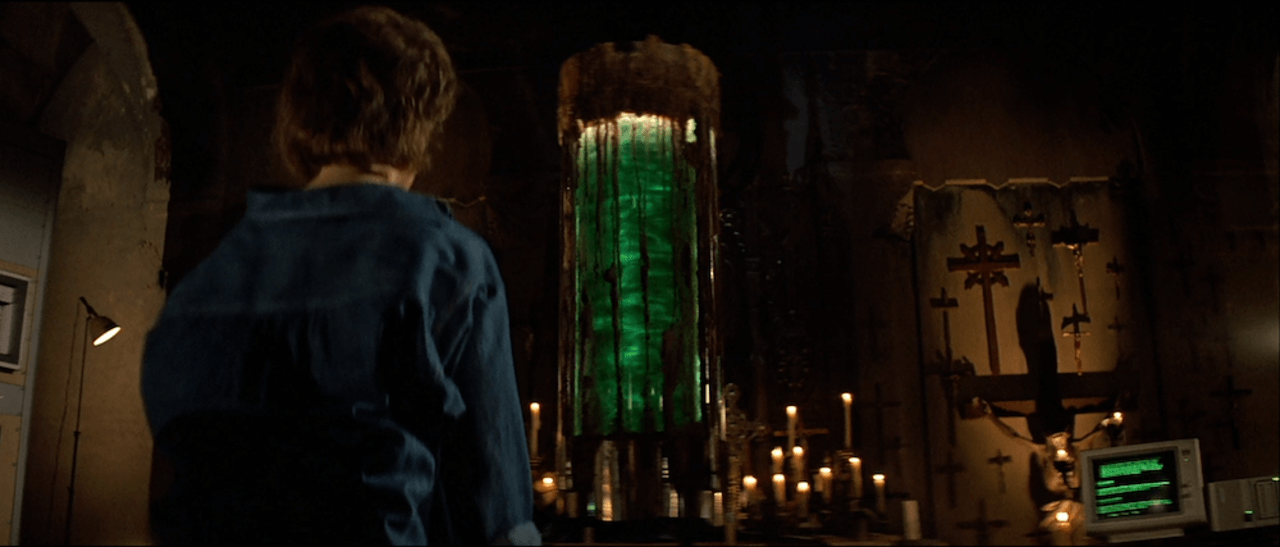

Prince of Darkness

Five years later, Prince of Darkness appeared, a 3 million dollar demonic horror film about the fact that if the Antichrist is to appear in our vale of tears, he will do so through a portal placed in an abandoned church in Los Angeles. Carpenter without embarrassment used a proven scheme – a group of scientists install themselves in a church to study a mysterious green substance locked in a transparent cylinder in the church crypt. Sounds tacky? That’s nothing! Writing the screenplay under the pseudonym Martin Quatermass (an homage to a series of classic British horror films with Prof. Quatermass, who also fights an unusual cosmic invasion), John Carpenter threw into one basket quantum physics, the mysteries of the Bible, temporal extrasensory communication and zombies branded with the ugly physiognomy of Alice Cooper. In a word, mess, which in the hands of a less crazy creator would even leak through fingers swollen with good intentions.

But John Carpenter was saved by style and atmosphere, with which he filled the holes in this phantasmagorical puzzle, full of absurd plot twists. Repeated in a much more severe form, the scheme from The Thing did not raise questions about the affiliation of the attacked scientists to the healthy fabric of society. The stony faces of the people assimilated by His Infernal Majesty were enough to know immediately before whom to close the door and check the locks (although some heroes traditionally showed blatant carelessness, but such are the laws of the genre).

Where’s the apocalypse? John Carpenter traditionally left the rhetorical question of whether Satan succeeded in a vacuum. Because, although the characters fought like MacReady on the Antarctic station, and the priest played by Donald Pleasence broke a huge mirror – portal at the last moment, the main character in the last scene reaches into another mirror to see if the prophecy still works. In Prince of Darkness, geographical and biological threats have been added to mental threats. Not only is man not surprised by the invasion of the Unknown – he even helps it, hiding the primal destructive instincts under the guise of scientific research. The next rung on the road to destruction has been reached.

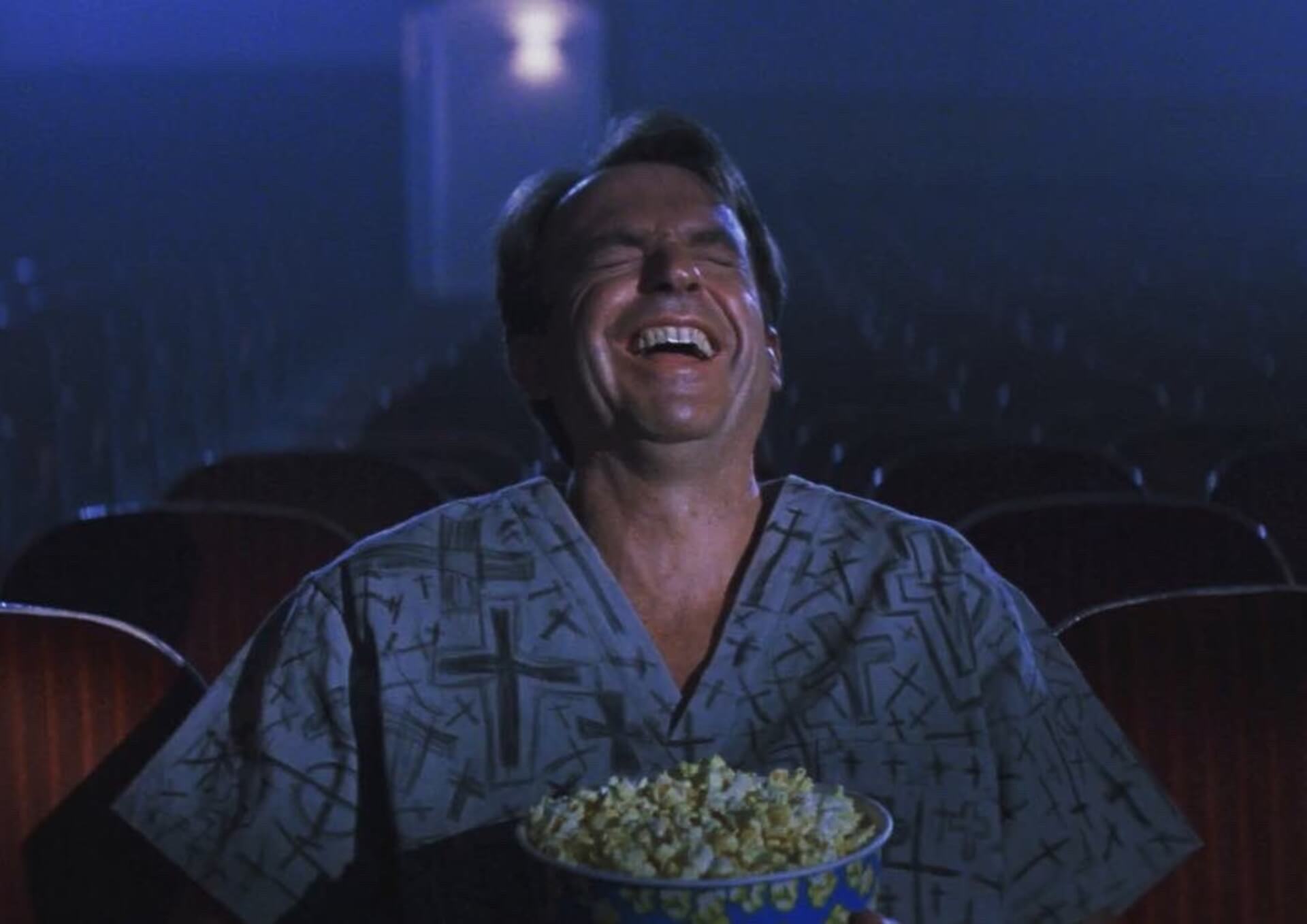

In The Mouth of Madness

The escalation of such a philosophy can only be achieved by throwing it to the prey of uncritical pop culture absorbers. Scientists fighting against the coming of Satan into the world were a laboratory sample of the desperate human thought. It’s time to bring the method to the street. There is a saying that Satan’s greatest success was convincing people of his non-existence. Writer and producer Michael De Luca figured out how to pull off the ultimate evil invasion with white gloves and the guise of high art. He included this truly diabolical plan in the screenplay In the Mouth of Madness, which he proposed to Carpenter in the late 1980s.

Destroy humanity with horror literature? Such a patent would be too much grace even for Stephen King, although it was to him that many viewers attributed the creative affinity, or even the source of the adaptation of In the Mouth of Madness. King’s self-referential obsessions with the plight of horror writers, which he has often referred to, must have worked here. Meanwhile, Michael De Luca’s original script was one big homage to H.P. Lovecraft, the American master of horror literature, the author of the Cthulhu mythology. Here, Carpenter’s apocalypse finally took on epic proportions, although on screen we only saw the story of insurance agent John Trent, drawn into the world of demiurgic horror writer Sutter Cane.

At the beginning of the film, Trent charged with cynicism and independence worthy of Snake Plissken. Landing in the non-existent town of Hobb’s End, he experienced the extraordinary, against which he tried to remain scientifically calm. In the end, he found himself where the title of the film informed from the beginning. The piling up of not being able to leave the world of small-town horror reached Carpenterian heights. Trent couldn’t physically leave Hobb’s End, running away and coming back to the same street over and over again. His publishing partner was successfully assimilated by Cane. Trent pushed himself into the abyss of madness, carrying out a client’s order with professional stubbornness. Finally, he took up the axe, killing the young reader of Cane’s novels in a gruesome sense of duty to a world voluntarily heading for destruction.

Where’s the apocalypse? Traditionally, it is suggested earlier – the viewer learns that Cane’s novels provoke inexplicable attacks of aggression by obsessed readers. And in the last act of the film, Trent left the abandoned psychiatric hospital (where he heard a radio broadcast informing about the global scale of the literary hecatomb) and, walking through the deserted streets of the city, entered the cinema showing… John Carpenter’s film In the Mouth of Madness with John Trent in the lead role. There, Carpenter’s hero made the final surrender, hysterical laughter agreeing to the inevitable change of reality.

Summary

These three titles do not exhaust the themes of destruction present in John Carpenter’s films. On the contrary – almost every of his works ends with an enigmatic suspension of action, but with a strong indication that “something has survived”.

Michael Myers, shot dead on Halloween, escapes, the apparitions of The Mist come back for their last victim, Snake Plissken in Escape from New York destroys a precious tape and cynically blows the fate of the world off, Christine’s compacted heap of scrap metal shows signs of activity, and the Chinese monstrosity still sits behind Jack Burton’s back in last shot of Big Trouble in Little China. Final Solutions from They Live or Escape from L.A. Compared to the above, they seem to be almost happy endings, which in their sweetest form were present in the form of Jenny Hayden, staying on Earth with the child of a star traveler, or Daryl Hannah, expecting a child of the hero of Memories of an Invisible Man.

So why did John Carpenter select these three films for the self-proclaimed Apocalypse Trilogy? Perhaps because the size of the apocalypse is consistently expanded in each of these films.

The Thing, Prince of Darkness and In the Mouth of Madness are three stories about the same thing, but in different stages of development. Although the word “development” is quite ironic here, because in the context of the inevitable expansion of Evil, it means rather the painful collapse of humanity in the shackles of foreign forces, eagerly taking full control over people and their proud, but extremely fragile bastions of science, faith and culture. John Carpenter’s crooked look at our civilization has something of Stanley Kubrick’s creative thought, although of course it is expressed in a much less subtle way – we can surround ourselves with scientific verism, life pragmatism, cold professionalism, common sense, strong faith or support for culture, and the Unknown and so he will find a way for us to get from these enlightened achievements of civilization an infallible diarrhea for which there is no remedy. Like MacReady, all we can do is wait and see what happens.