10 Essential Movies To Begin Your Samurai Adventure

And it’s not just Akira Kurosawa, the undisputed master of Japanese historical cinema, but someone too confined within rigid frameworks that are worth transcending. This was the premise that guided me in creating this list. It’s not easy to encapsulate the samurai world in just 10 entries, but I treat this set as a starting pill, aimed at all those who are just beginning their adventure with samurais.

Of course, to better understand this type of cinema, key readings are also essential—starting with the absolutely necessary big three: A History of Japan by Conrad Totman, An Introduction to Bushido by Shigesuke Daidoji Yuzan, and The Samurai Sword by Hakusui Inami. AND A CERTAIN DEGREE OF DISTANCE. So everything I write about samurais will always be just a reinterpretation of their myth through my Western, European understanding of their culture. It’s worth being aware of this because, in our admiration of this warrior caste’s culture, we often create more myths about them that are far from the truth and dangerously romanticize them. And I intentionally don’t mention the 1980 series Shogun by Jerry London, although metaphorically it is present in this list. I will dedicate a separate text to it along with the latest TV adaptation of James Clavell’s book.

The Hidden Fortress, 1958, dir. Akira Kurosawa

It’s a bit of a road movie. Although critics often debate its genre classification. It’s simultaneously a samurai film and an adventure film, with a significant nod to the American Western, specifically to John Ford. The Japanese title can be literally translated as The Three Bad Men in the Hidden Fortress, which is a reference to Ford’s 1926 film Three Bad Men. And that was a Western. Kurosawa’s cinema has a lot in common with this genre, although it might seem improbable to some. However, the three men in this film aren’t really that bad. Two of them form an almost comic duo of hungry peasants/mercenaries exploited by the feudal system. The third man is the warrior General Rokurota Makabe, played by the statuesque yet witty Toshirô Mifune. The trio meets to escort a princess, the heir to a besieged empire, to a safe place. The entire group travels through enemy territory. The Hidden Fortress is a comedic film with samurais in the background, yet its message is serious and concerned with the state of Japanese society. Kurosawa strives to promote a humanistic ideology, hoping his cinema will contribute to building a new, democratic reality after the war.

As for the samurais themselves, before the Tokugawa era (1603–1867), from which we inherited many myths about Japanese warriors and the Bushidō code associated with them, samurais could—according to Kurosawa’s cinematic mythology—act based on their conscience rather than their lord. They weren’t as mythically evil, unyielding, and loyal. This is reflected in The Hidden Fortress through the character of Rokurota, who allows his rival to live after defeating him in a duel; and Tadokoro (Susumu Fujita), who lets Rokurota and Yuki go later in the film because he hears Yuki’s song.

So if you come across this light and stylistically classic film, consider how cleverly Kurosawa depicted the fate of the two peasants, from the hell of the burning fortress at the beginning to their understanding of humility and generosity at the end. Who knows, maybe it’s a metaphor for the changes in Japanese society after the painful experience of fascism and the atomic war?

Throne of Blood, 1957, dir. Akira Kurosawa

Throne of Blood is the first of two Shakespeare adaptations by Akira Kurosawa (the second being Ran, an adaptation of King Lear) set in feudal Japan. For 1950s Japan, whose cinema was recovering after a devastating war, this was a revolutionary approach to Macbeth, in which Toshirô Mifune played Washizu, a warrior psychologically manipulated by his wife (Isuzu Yamada) into attempting a hostile takeover of the Spider’s Web Castle to fulfill a prophecy. The path to power is rough—filled with crimes, and the price for them is incredibly high. The film certainly deserves discussion as a direct adaptation of Shakespeare’s timeless text, but it stands out because it is set in medieval Japan.

So, let’s set aside filmic considerations about the semantics of Kurosawa’s Shakespeare for a moment and focus on the form of Throne of Blood, which is key to the reception of this production and its uniqueness. Throne of Blood is primarily a visual interpretation of Shakespeare, rather than a linguistic one. Where European adaptations have always struggled to maintain a cinematic (entertaining) character due to the difficult language of the drama text, the Japanese version gains immensely by not having to stick to the original English version. Paradoxically, the spectacle becomes digestible for the viewer because it is—colloquially speaking—”normal” in its language. Kurosawa’s approach was genius in its simplicity. The viewer could finally focus on the emotions and didn’t have to constantly translate old-fashioned text into a contemporary, understandable language.

As a result, the audience could concentrate on the visuals, and the visual presentation of Throne of Blood, even in black and white, is dazzling. Thus, the Japanese version of Shakespeare is much more cinematic and not exhaustingly theatrical, unlike most European adaptations of Shakespeare. Every frame of Kurosawa’s film looks like a painting. The landscapes are cleverly designed to look great even without color. Battles take place on vast, mountainous fields, providing a great sense of scale. The Spider’s Web Castle is partially real, built with the help of American soldiers stationed in Japan at that time.

It’s worth comparing the ethos of the samurai to the ethos of the main character and asking whether they are that far apart.

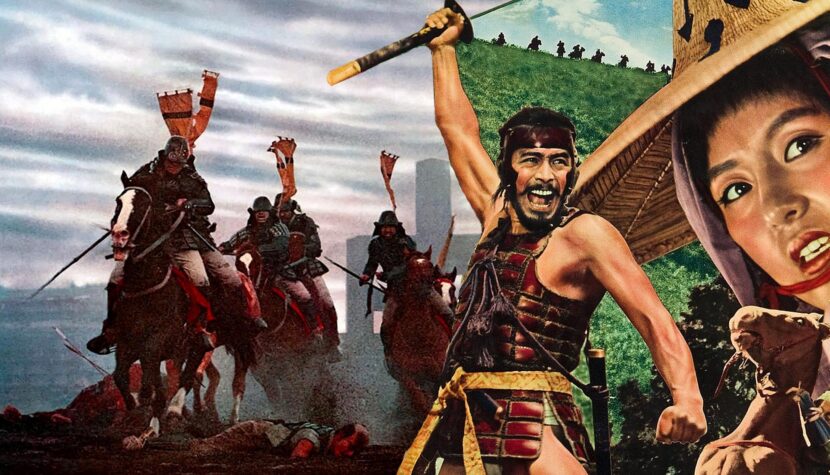

Ran, 1985, dir. Akira Kurosawa

Compared to the two previous productions this Kurosawa film was revolutionary aesthetically, if only because of its use of color. Let’s focus on just one element, and we’ll understand the director’s mastery. Kurosawa placed huge armies in vast outdoor settings, showcasing his superb technical skill without digital tools. Today, we can only marvel at this when we look at the castle siege sequence, especially if we have some idea of how similar scenes are shot today. In Kurosawa’s rendition of King Lear, once again, we see the same easy linguistic delivery and dazzling visuals. However, few people know how difficult it was for Kurosawa to make this film—how much effort it demanded of him, almost samurai-like, a tradition he was familiar with, coming from a family with such heritage. He made the film, transposing Shakespeare, but he was thinking of himself.

Kurosawa was an undisputed legend of cinema at that time, but – as it turns out – only a legend. It was the 1980s. His golden period was from 1950 to 1965. From 1965 to 1985, he made only a few films. He didn’t fit in with the changes occurring in the film industry, and his career in Hollywood didn’t succeed. His attempt to create an independent production with Dodes’ka-den (1970) ended in financial failure, despite an Oscar nomination. A year later, Kurosawa cut his wrists and throat. Depression returned along with the burden of childhood experiences. During production, Akira Kurosawa had to deal with the death of his wife. According to legend, he took one day off to mourn her death and returned to work the next day, not missing a single day of production afterward.

Lady Snowblood, 1973, dir. Toshiya Fujita

Now for something completely different – kitsch, B-class, and feminine samurai revenge. I recommend this title precisely because of the cheap chaos present in it, as its low-budget nature is pushed to the highest level. The direction appears chaotic. Carefully composed, mostly static images alternate. The narrative suddenly shifts in a completely fragmented chronology; Fujita regularly interrupts the action with sudden, brief flashes of Yuki’s memories as she coldly kills successive men. Lady Snowblood is a pulpy yet gripping, brutal tale of revenge based on a comic book. Originally simpler in form, director Toshiya Fujita treated it as experimental material, using a complicated structure of flashbacks and expressionistic shots to tell the story of Yuki Kashima, a highly skilled assassin trained from birth to find and kill the men (and women) responsible for her father’s murder and her mother’s rape. Her nickname ‘Shurayukihime’ is a wordplay equivalent of the Japanese name for Snow White: ‘Shirayukihime’ (‘white snow princess’), reflecting her cold, grim beauty. Yuki found her perfect embodiment in Meiko Kaji, an icon of feminine beauty in 1970s Japanese action cinema. She skillfully dispatches her opponents with swift wrist movements wielding a sword, embodying what Japanese swordsmen describe as the boundary between life and death, while fake blood theatrically spills from the screen as intensely as possible.

However, one of the retrospective scenes deserves attention. Yuki practices with her master. At one point, she undresses; she is a little girl, flat-chested, hairless, completely a child. When the master sees her naked, he smiles significantly, as if he liked or was excited by the sight. But she fights. She does not want anything else from him. Then his expression changes. This scene, suggesting the master’s pedophilic tendencies, is deeply rooted in Japanese culture, a topic I would recommend exploring further, perhaps in documentaries like those by Stacey Dooley.

, 2019, dir. Bernard Rose

If someone is looking for something fresh in samurai cinema that is also deeply rooted in history, they will find it in Samurai Marathon. Let’s start with the fact that on July 29, 1858, Japan signed a trade treaty with the USA, shortly followed by treaties with the Netherlands, England, and other European countries. Around the same time, the childless shogun Tokugawa passed away, triggering a struggle for succession between factions. From 1859 onwards, foreigners began flooding into Japan, breaking its two-century isolation. Naosuke Ii came to power and attempted to negotiate with the West while maintaining internal support for the shogunate. This caused opposition, and in 1860, Ii was assassinated. The Edo period came to an end, and Japan entered the Meiji era under Emperor Mutsuhito, a time of rapid political, military, economic, and social reforms heavily inspired by Western powers.

For the film Samurai Marathon, a crucial historical backdrop is the Meiji era’s abolition of feudal privileges, effectively equalizing the samurai class with the rest of society. Initially, former samurai received pensions from the state, but this was later replaced with one-time compensation. Perhaps most painfully, public sword-wearing was prohibited. Samurai Marathon tells the story of the period just before these changes, still within the Edo period, when trade treaties had not yet been signed but were only months away. Katsuakira Itakura, stationed at Annaka Castle, fearing these impending changes, decides to organize a race to bolster the fitness of his samurai, preparing them for the impending conflict.

From Japanese history, we know that such an event did indeed occur, known as the Ansei Tōashi or Ansei-no-Tōashi. It was a footrace open to samurai from the Annaka domain, spanning approximately 30 kilometers, also known as the Samurai Marathon. This event was forgotten for many years but revived in 1955 after the war. Annually in Annaka City, long-distance races commemorate these historical events from the Ansei period. Towards the end of the film, you can see how the marathon looks today: in black and white footage, everyone—young and old—participates, some in traditional runner’s attire and others in cartoon character costumes. However, in the film, the samurai marathon is not just physical activity but a race for life due to unfortunate circumstances and misunderstandings.

The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi, 2003, dir. Takeshi Kitano

It is often said that the character Zatōichi from the Edo period serves as an inspiration for James Bond, albeit within different political systems. Nevertheless, he is one of Japan’s oldest heroes in the style of Robin Hood. Zatōichi appears to be a harmless blind masseur who travels the country and gambles, but there is something distinctive about him. He excels in swordsmanship, particularly in iaijutsu, the technique of swiftly drawing the sword and responding to an opponent’s attack. Zatōichi’s sword is concealed within a special cane used for support and examining the surroundings, known as a shikomi-zue.

Many directors have made films about this character over the decades. It’s worth exploring the works of Shintarō Katsu, for instance. Additionally, a much more internationally recognized director of Japanese cinema, Takeshi Kitano, also tried his hand at portraying Zatōichi. He created a title that was very classical, respecting the samurai tradition, although according to Japanese legal history, Zatōichi cannot be called a samurai. In practice, however, he is treated as one. He is a ronin who fights for the common good, not a mindless executor of a feudal lord’s will.

Samurai Fiction: Episode One, 1998, reż. Hiroyuki Nakano

Is it a samurai comedy? Yes and no. It’s worth watching carefully and even jotting down moments when color appears on screen. These moments are significant for the overall narrative. The story revolves around a sword given as a gift from Shogun Tokugawa. Conrad Totman beautifully tells the importance of this figure in Japanese history in the book I mentioned earlier, A History of Japan. The quest for the sword is merely a pretext to present a story about the idea of being a samurai. Did this idea ever make sense, considering the feudal dependency on daimyō was so strong? Just as a reminder, in brief: At the top was, of course, the Emperor, whose power came from the gods. The Shogun, in his name, wielded administrative power throughout the country, but couldn’t do so without managers. These were the daimyō, who ruled their own provinces on behalf of the Shogun. Samurai were directly subordinate to the daimyō and emerged as a separate warrior class in society. Below them were peasants, craftsmen, and traders. Medieval Japanese society was highly stratified with clearly defined economic and political roles. The Shogunate, a government led by the Shogun, maintained its power by appointing daimyō and forming alliances with them, which sometimes weakened central authority, despite the complex system for controlling daimyō to prevent conspiracies. Daimyō, in turn, managed their provinces, delegating land and executive duties to loyal samurai. Many samurai films explore the extent of this dependency and its justification in bushidō, the ideology samurai were expected to uphold. Samurai Fiction: Episode One also poses this question, albeit in an intriguing form, featuring sword fights accompanied by rock music.

The Last Samurai, 2003, dir. Edward Zwick

A grand, melodramatic, epic, superheroine, crystalline tale of the last stand of traditionalists to save their honor, because changing the political situation is out of the question. And for this panoramic view, we should appreciate this film. It’s sentimental, exaggerated, sometimes exhausting, yet visually stunning. Edward Zwick fulfilled his dream, and battle scenes are not unfamiliar to him, so he was able to execute them practically. However, if someone is seeking historical truth, they might be disappointed because The Last Samurai is not that kind of cinema, much like many films about samurai, including Japanese ones. The Last Samurai is an epic tale of clashing ideals, based on historical events. Such an approach is entirely natural and should not surprise anyone. For history, one can read books or watch interpretations in documentary programs. In Zwick’s film, we depart from the scientific perspective, although as I mentioned at the outset, it’s important to know it. We watch this film and try to emotionally experience what perhaps not the heroes of 19th century Japan themselves, but the actors portraying them, went through. Their dedication to the production was immense. It’s worth exploring how Ken Watanabe and Tom Cruise prepared for their roles. It’s admirable. The film’s structure also deserves praise, especially how skillfully the director and screenwriters managed to simultaneously merge and delineate the film’s war and emotional dimensions as impenetrable planes.

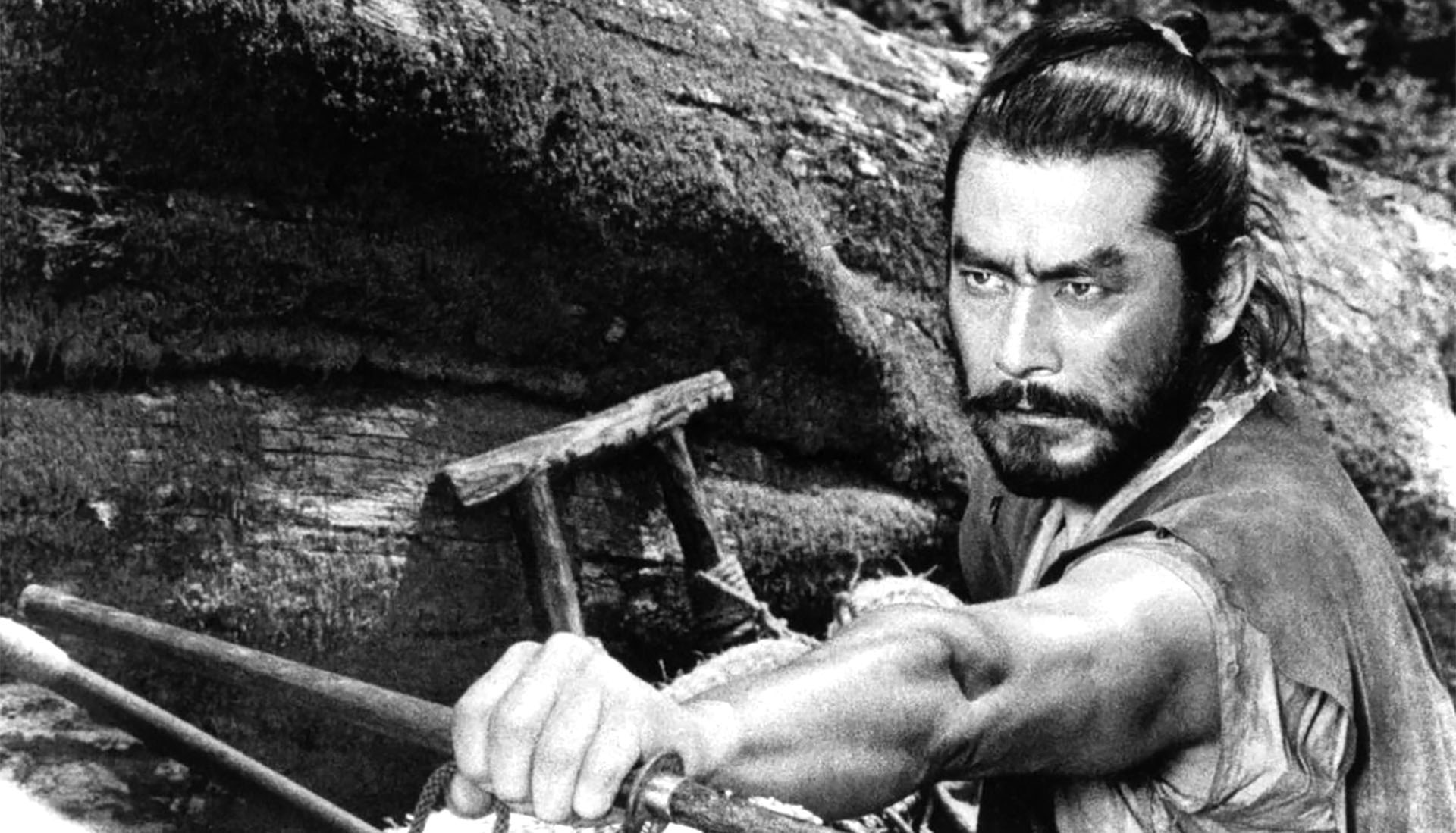

Seven Samurai, 1954, dir. Akira Kurosawa

Let’s appreciate both this legendary film and Akira Kurosawa’s overall oeuvre – his influence on motifs permanently present in our Western cinema. Seven Samurai is not only a magnificent film in itself but also a source of immense inspiration, not just for John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven, but also for The Dirty Dozen and Star Wars. It’s a very masculine film – such were Kurosawa’s times. Each character is solidly characterized. Toshirô Mifune as the bold, wild, yet courageous warrior creates a timeless portrait, overshadowing the supporting roles. The cinematography is also excellent, as is the editing, skillfully blending dialogues and creating monumental and thrilling battle scenes, as always monumental and exciting in Kurosawa’s style. The music also enhances the mood, alternating between Western and Eastern motifs for the best effect.

In the film, Kurosawa asks the question: What does it take to be a trustworthy samurai? The samurai identity is as mythical, multifaceted, and almost fluid as water, and through Kurosawa’s reflection, it can be redefined anew. This dynamic of exclusivity and inclusivity forms the core of Kurosawa’s storytelling. According to the director, the samurai is almost a contemporary, eclectic warrior figure, simultaneously capitalist and communist. This multi-image is presented with impeccable realism, magnetic to all who are not samurai, so they too can become one. Anyone can be a samurai, regardless of whether they possess a sword. Therefore, the samurai is egalitarian, not elitist, as we often assume.

Blue Eye Samurai, 2023, creators: Michael Green, Amber Noizumi

When I replay certain scenes in my mind, I’m so enthralled by them that I wish to see them in live-action rather than animated form. Then I realize that only a film genius could bring them to life while maintaining a balance between pathos and mature drama, without turning them into sugary pastiche. Blue Eye Samurai is a thoughtful adaptation of classic samurai motifs from numerous historical productions—it’s Kurosawan revenge cinema, Okamoto’s critique of feudal injustices in the Edo period, and Yamada’s romance with sword and honor in the background. All of this is sprinkled with contemporary Japanese eclecticism, including its approach to aesthetics, sexuality, issues of equality, and gore.

Blue Eye Samurai is a magnificent journey into the world of samurai history, which, despite the sometimes overly grandiose packaging for Western audiences, is essentially an entertaining genre of film, akin to cloak and dagger tales but in an East Asian setting. And what about the intersex samurai? Could that work after all?