The Seventh Seal. Ingmar Bergman’s masterpiece explained

“The skull is more intriguing than a naked girl,” claims Albertus Pictor, a painter working in the church. It’s good to frighten people from time to time. The thought of their mortality induces fear, and the more they think about death, the more they fear it. Perfect, as they then fall into the clutches of priests, for whom death serves as a whip for the rebellious nature of mankind. However, in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, Death is unaware. It’s not an instrument, neither divine nor diabolic. It’s hard to believe, especially since the eyes of Bengt Ekerot, who plays Death, say more than his lips do – Observe carefully. You’re not a complete fool, so you’ll understand. I’m always trailing behind. If I don’t catch up with your loved ones right now, at least I’ll have you. Bergman pretends to know everything about death. Meanwhile, he fears it just like the main character in his film because he doesn’t know the answers. The Seventh Seal is an ironic, extremely personal, and so serious film that it inadvertently enters the territory of black comedy. Moreover, it is a cinema from “bygone ages,” which still pretends to be theater.

Return of the knight

During the Middle Ages, if someone traveled, it was most often for a pilgrimage or a crusade. Unfortunately, both of these activities were associated with death. Merchants and officials also traveled, but the idea of tourism as we know it today, i.e., exploring the world for pleasure, did not fit into the average person’s mindset. Enjoying oneself was not considered appropriate in the eyes of God. Human beings were seen as fitting perfectly into the role of God’s livestock. They could be shorn, wounded, starved, humiliated, and finally, when they could no longer rise from their knees, ritually slaughtered. Bergman takes us into such a reality in The Seventh Seal. Its main character, the knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow), fits perfectly into that somber atmosphere, and the scene on the seashore reflects the monolithic, heavy, and prolonged atmosphere of the Swedish genius’s film, which will remain with the audience until the end.

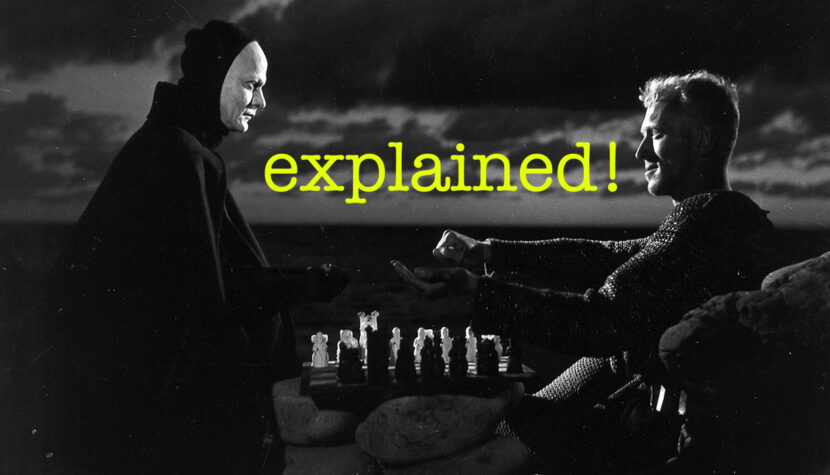

We meet the returning crusader knight as he sits over a chessboard, in a pose somewhat reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Adam. On the other hand, his squire Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand) lies like a proverbial sack (or corpse) on the rocky beach. This is not to suggest that there is any class or cultural difference between them that matters for the relationships presented in the film. Of course, there is, and it is a vast divide, but more in terms of the perception of the early medieval reality. The knight constantly questions whether there is something more, whether God exists, or if there will be a better world after death. He also links his sense of self-worth and readiness to leave the world of the living to finding answers to these questions.

Jöns, on the other hand, doesn’t ask as if he already knows all the answers, and in a negative sense. Certainly, no supernatural force would be interested in such a life’s malcontent. It’s different with Antonius Block. Death appears faster than anyone could have imagined, especially for an audience accustomed to the gradual development of suspense. Apparently, Death is very bored with taking the lives of people who, in those times, live too short to learn to ask meaningful questions about the meaning of life.

The Seventh Seal is a low-budget film made in Europe in the 1950s, specifically in Sweden, a country not specialized in the film industry like France, the United Kingdom, or the USA. Consequently, the audience won’t see Antonius Block returning from the holy war on a meticulously reconstructed port with all the costly production values we often encounter in modern films. There are no lavish introductions, exotic outdoor locations, or meticulously recreated period costumes. Instead, there are symbols: overcast skies, a black bird, the murmuring sea, and a ominously quoted verse from the Apocalypse of St. John 8:1.

Perhaps that’s why within the first five minutes of the film, we learn everything about the main theme. With a runtime of just over ninety minutes, the director doesn’t waste time, and there are many themes to explore. In the subsequent scenes, the main problem of existence is further developed and philosophically refined, which may cause quite a headache for many unprepared viewers not accustomed to theological-ontological reflections. So, what is the core of The Seventh Seal?

Indeed, it is known why Death appears, considering the knight’s situation. Returning home after ten years is not easy for Antonius Block. He doesn’t even remember what his wife looks like. Apparently, he once loved her, but time and the bloodshed of his profession have overshadowed those memories. However, the knight is well aware that everything he did during the crusade follows him. No matter how you look at it, Death is following him, and it is precisely in the form of the familiar figure from folklore, clad in a black cloak and wielding a scythe, that Death appears on the seashore with the intention of ending the knight’s life full of deadly adventures.

Antonius Block, however, has no intention of surrendering to Death so easily. He devises a scheme to prolong his life a little longer and uses the immortal guest to find answers to his tormenting questions about the meaning of existence. He proposes a game of chess to Death.

Related:

Innocence in the Time of Plague

The world depicted in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal can be defined as the prolonged agony of human society, where some individuals try to seize moments of pleasure for themselves. From one hell, Antonius Block and his squire enter another. The plague reigns. People are dying literally on the streets, and pervasive religious fervor becomes a lucrative tool for the Church to enrich itself with power over souls and treasure chests from remorseful nobles and starving paupers. Death comes to all, while no coin tossed into the begging pouch for supposed divine punishment indeed smells of death.

The wise clergy knows that the plague will eventually pass. Those who survive will be even more favorable towards the newly adorned churches filled with paintings of death’s subliminal images than before the epidemic. After all, one must prepare for the next attack of divine punishment and gather enough kindling for the pyres in advance. People will come to kneel in the renovated temples. Their medieval sense of guilt towards their dirty, pleasure-seeking, and joyful nature still cannot stand on socially sound ground. They continue to atone, and plagues still sweep through the world like changing seasons. However, none of them are the apocalypse, although the penitents still prophesy it.

The world view of “The Seventh Seal” is poignantly expressed by Antonius himself during his confession. As a learned man immersed in religious piety, when he sees the dark figure behind the confessional grille, he immediately assumes it is a priest. He never suspects that Death herself is listening to his confessions. And there is much to confess. Perhaps only Death can bear the weight of such words.

The moment of Antonius’ confession is the climax of the film, a counterpoint to the entire picture, although it occurs in the nineteenth minute of the production. Nothing as sincere will be heard from him again. The mirror of emptiness is turned towards the knight’s face. Nothing else matters now, except one thing – seeking the truth. Why does God hide behind the fog of promises and invisible miracles? – Bergman asks through Antonius’ words. Does it not make it easier for an entity molded from human frailties? – the figure of Jesus seems to respond, resembling more a decomposing corpse than a sculpture. “I want to know, not to believe!” demands the knight. “Because if there’s no one there in the dark, life is an absurd nightmare. You can’t live constantly in the face of death and the conviction that everything is nothingness.” And what does Death have to say about that? “Most people don’t dwell much on death and nothingness,” she replies curtly.

Both of them are right. It’s not possible to live like that, which is why most people don’t think about it. However, does this resolve the problem of the senselessness of life in the face of inevitable death? Bergman will seek the answer to this question in many subsequent films. Eventually, he will discover that there is nothing more (The Silence) and thankfully, for the sake of his further creativity, he will delve into the dissection of humanity (Autumn Sonata, From the Life of the Marionettes, Fanny and Alexander). For now, he can only conclude that despite death, there is a moment in a person’s life when they realize the meaning of everything, their entire faith, and existence. Like the witch burned at the stake, whose dying mind suddenly discovers that BESIDE THE MOON, IT IS EMPTY.

The director skillfully utilized the character of Death, deliberately dressing it in a human, white face rather than a skeletal mask. This portrayal allows the audience to identify more easily with Death than in the case of modern examples like Johnny Blaze (the skull-faced Ghost Rider) or Gollum (The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit). These are contemporary examples that utilize unimaginable special effects not available in the filmmaking of the 1950s.

Let’s recall a film closer in time to “The Seventh Seal,” although with a completely different meaning. The globally known character Fantômas (played by Jean Marais) wore a rubber mask. Fortunately, he did not perform in a production requiring complex facial expressions, as the mask would have limited his ability to convey emotions effectively. However, Death (Bengt Ekerot) in Bergman’s film faces no such limitation. With his powdered white face, he symbolizes both human unconsciousness and the propensity for destruction. He tries to deceive the knight because he also desires the death of his companions, but the crusader realizes this in time.

In Bergman’s portrayal, Death is devoid of ideology. Antonius struggles in vain because Death does not possess consciousness. It simply IS, and this existence is in harmony with nature, even though it is loathed by culture and civilization. The most distressing human act is creating symbolism from facts that, due to their as-yet-unknown scientific structure and content, appear to transcend reason and activate the imagination that craves for God. The burning of the witch in the film was an act carried out by people because some deemed her to be a witch, while others believed that being a witch was against the will of the Almighty. People, people, people, human, enslaved reason…

Theatrical cinema

The Seventh Seal is a film centered around two actors. One of them, Max von Sydow, thanks to Bergman, achieved worldwide fame, while the other, Bengt Ekerot, didn’t succeed in a similar manner. Ironically, Death quickly caught up with Ekerot. Among the other significant characters, we must mention Jöns, the squire, portrayed by Gunnar Björnstrand, but his performance doesn’t impress. One cannot deny his theatrical skill and expressive use of his face and body. However, for someone viewing the role from the perspective of someone living in the late 20th century, this theatrical emphasis appears more like a recitation contest than a part in a serious film. At times, it becomes so serious that one feels like laughing, while the characters become increasingly humorless, especially under the dramatically drawn lighting on their faces.

If we were to evaluate Ingmar Bergman’s film from a technical standpoint, a fair rating would be, let’s say, three out of five. The camera work is too static, and the editing is flawed. The editor seemed indecisive about whether to edit in a “hard” or “soft” manner. A prime example of the flawed editing in The Seventh Seal is the shot of a fallen tree trunk with a squirrel climbing onto it. The animal appears after an obvious jump in the film, on a much darker illuminated trunk, even though theoretically it should be the same tree trunk. A similarly unnatural jump occurs a moment earlier when Death, cutting down a tree with Jonas, barely touching the bark, suddenly fells a thick tree trunk. As for other editing mistakes, one can generally say that there are too many unnaturally fast transitions between scenes, often disrupting the flow of the narrative. This occurs, for instance, between Antonius’ confession and the scene where the squire Jöns drinks with the painter Albertus. More breathing space would be beneficial. When one intends to change the location and emotional load in successive cuts, it is worth giving these concluding scenes a chance to reverberate appropriately in the viewer’s mind.

The Seventh Seal may be a thematically perfect film, but it does have its technical flaws, likely resulting from the editing process or the constraints of not being able to reshoot some scenes. For instance, the chase of the blacksmith’s wife in the woods abruptly ends near Jof’s cart, while in the previous scene, they were running in a completely different direction. Also, it seems implausible for Antonius, traveling on horseback, to arrange the chessboard. During stops, we often see him pondering over the board, but while riding on the horse, he doesn’t hold it like a waiter carrying a tray of glasses. The game with Death continues, and the positions of the chess pieces change. Does the knight have such a good memory, or perhaps the enchanted chessboard itself remembers the positions of the pawns? Adding to these inconsistencies is Jof’s artificially marked lute playing and the rather poorly simulated twilight. I understand that creating a simulated low-hanging sun with lighting in a black-and-white film isn’t easy, but in The Seventh Seal, this shaded, albeit diffused light, is barely visible. The twilight looks like a cloudy day.

There are numerous technical flaws in The Seventh Seal, despite it being a thematically excellent film, or perhaps a flawlessly staged performance. To understand it, Bergman requires an open and flexible mind from the audience, one that can feel and interpret emotions such as fear and joy without reveling in each one separately. Such minds are undoubtedly possessed by the members of the Monty Python group, who in one of the final scenes of The Meaning of Life used the motif of Bergman’s Death dancing with the drifting victims. There was also a nomination for the Palme d’Or in 1957 and a Special Jury Prize.

Bergman drew disconcerting conclusions about our world. Most people hide from the most difficult questions, concealing themselves like children facing punishment for eating a few too many candies. Contemporary society has taken such a shape that now we all have the possibility of being “behind,” hidden behind some electronic curtain (symbolized by actor Jof’s disguise). On the other hand, despite voluntarily revealing ourselves virtually, we lose the natural awareness that the one in front, our observer, will always be a stranger. We won’t experience the weight of their burden, their thoughts about death, or death itself when it comes. Everyday life confirms these facts. Death on the screen excites us, but on the street, tangibly close, it repels us. It’s best for us if others die behind screens because we fear the end of life so much that we can’t even look at someone’s terminally ill behind without feeling nauseous and the fear it triggers.

Death in The Seventh Seal hides her face because she wants to eavesdrop on the knight’s thoughts. This simply means that she knows nothing about him, so she can’t be certain about what the man thinks of her either. However, the knight rarely asks, so he lives in mental concealment. Due to this, he cannot recognize who she is and also cannot stop being afraid of death. The circle remains closed.

On the other hand, our “behind” is only accessible to someone who is not us. That someone experiences the same feigned torments as us, looking at our end, while we must experience it for real. This is not a paradox, but a logical and safe solution. Death is not for show, sale, or sharing on Facebook. We won’t know other deaths except our own. It is the most intimate experience that we can’t share. We have to create an image of our fear. And then we will call it either the Seventh Seal or God.