CRIES AND WHISPERS. Death, pain, grief and guilt

The atmosphere of confinement and powerlessness pervaded from all sides, weaving a delicate yet dense veil of nightmare. Then came the film.

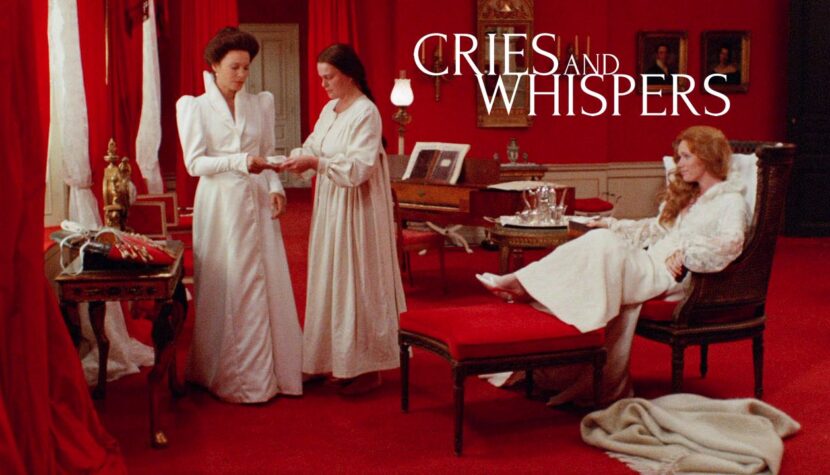

In Cries and Whispers, Bergman’s next psychodrama, all the threads of his work unfold like a kaleidoscope. Starting from childhood memories, through the ‘hell of gender,’ to the experience of death. Three magnificent actresses – Bergman’s Three Graces – and his grand theme. Also, Sven Nykvist and his photographic artistry. All of this to give the misty and ephemeral dream a lasting form of a masterpiece. The cohesive and decisive color tone of the film – simple yet persistently imposing its presence – primarily encompasses red, with white and black against its backdrop. The use of saturated colors serves not only to outline a state of unreality and isolation but also intensifies the overwhelming feelings of anguish, tension, lack of freedom, suffocation…

There’s a suggestive power of colors that makes the viewer feel like they’re dreaming this nightmare. There’s also their symbolic power, which unmasks the true faces of the three sisters…

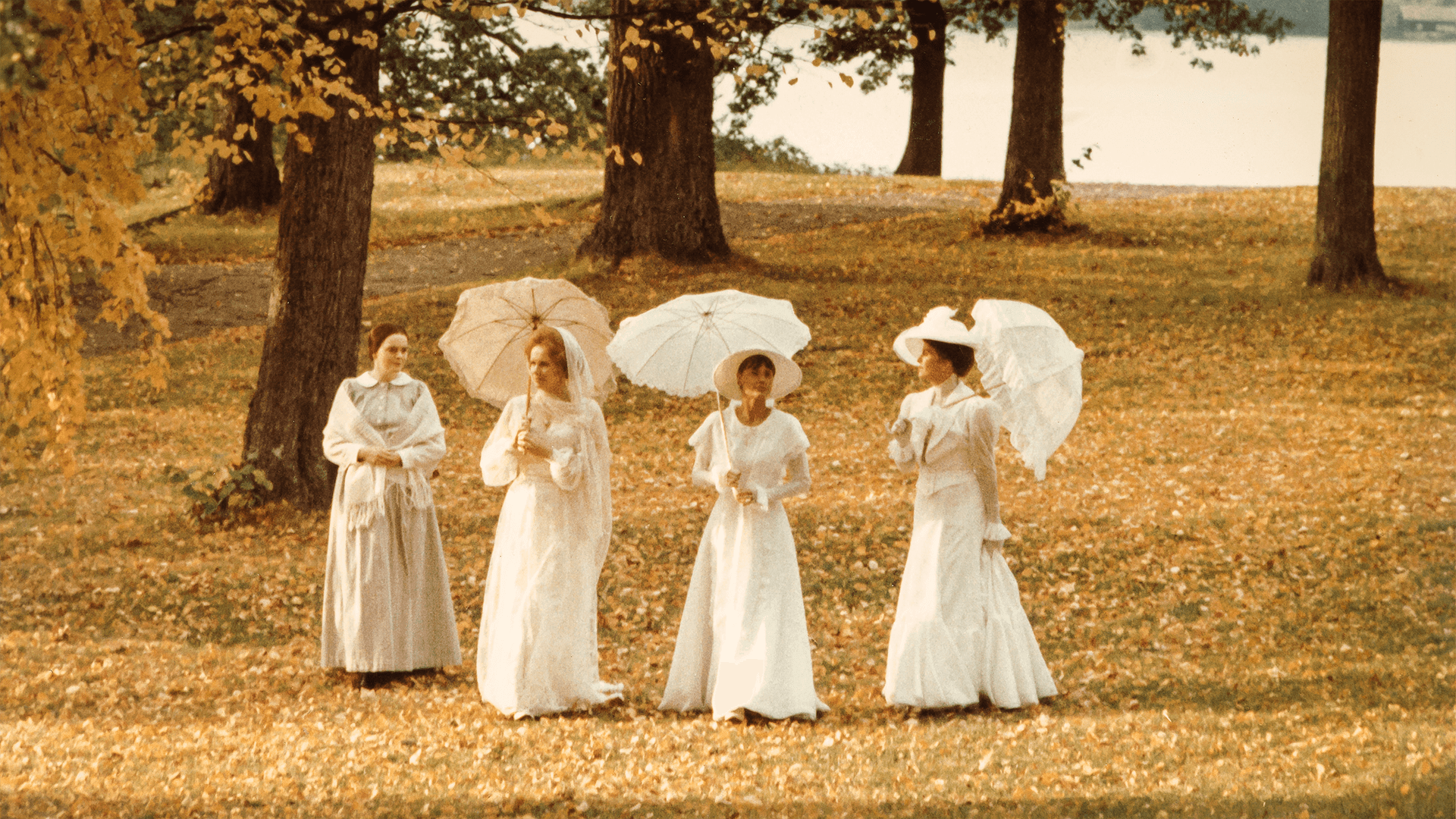

The initial sequence of the film, maintained in a cool, ‘refreshing’ tone, allows for a long inhale before the viewer is engulfed in the ‘breathlessness’ of the red salon (Agnes dying there gasps inhumanly, trying to catch her breath; the windows are invariably shut, and huge curtains fall heavily to the floor). The final sequence, on the other hand, allows for a sigh of relief. The air, which can finally be drawn in, almost becomes palpable in the frame. The space of the park, enveloped in lush greenery, becomes the ultimate liberation and return to the lap of nature. It’s the only true moment of happiness for Agnes. Into the morning silence of the misty park, time brutally intrudes. The rhythmic, loud ticking of the clock reminds of its intrusive presence. The huge hand moving across the dial marks the rhythm of all the day’s rituals. In the red salon, no unnecessary words are spoken; the passing of time is still audible. This time is waiting for Agnes’s death.

At four in the morning, she is awakened by a painful cramp. The grimace on her face deepens the lines around her mouth, silently screaming. At four in the morning, it is inappropriate for anyone to confess to the premonition that death is near. One can gaze out the window at the receding world, which is no longer real or friendly. And it’s not worth remembering it at this moment, so it’s easier to part with it. Just maintain this ritual. Write a few pages in the diary in the hand of a reporter. Without unnecessary emotions. Without regret.

In the film, Bergman touches not only on his constant theme of the ‘disease unto death.’ He doesn’t base this story solely on the opposition of life and death. The stamp of death lies dormant and becomes the cause of the omnipresent chill in human relationships. The problem of reconciling this feeling, this crushing emotional impotence of the characters, became almost a psychoanalytic introspection for the director. Not without reason, the image of the mother recurs in retrospections. A beautiful, gentle woman living in dreams. She absolutely should not have been the mother of her three daughters. In part, they now atone for her alienation and selfishness.

In the memories of Agnes, isolated from childhood, there is a record of her mother’s empty chair left in the park, where she used to read poetry. Maria, half-asleep, only remembers an exaggerated dollhouse, where everything has its perfect place. The ticking of the clock turns into a distorted dull sound… Maria has come closest to her mother. She is eerily similar to her. In the same carefree way, she embraces life, dallies with men, and feeds her selfishness.

Karin is a woman with no memories of her mother. She has had an autistic childhood. She smiles only with irony. Constrained by a rigid corset, she reacts panic-stricken to touch. The thought of sex, the hated duty of marriage, with her equally rough and dictatorial husband, causes her another bout of self-harm. With learned calmness, she embeds a piece of glass in her vagina and covers her face with her own blood in front of her shocked husband. Hatred, cynicism, and the lack of spontaneous feelings intensify the action of the death drive. Only blind obedience to bourgeois conventions keeps her from the brink.

Death attacks the source of life. Agnes dies of uterine cancer. Her spirit returns wandering somewhere in between… ‘I died, but I can’t sleep. I can’t leave you. No, this is not a dream.’ Agnes’s voice emerges from her lifeless body, forcing her sisters to bid her farewell. They recoil with disgust from the corpse’s embrace, trying to converse with her motionless body. They scream that it’s absurdity. That she should be ashamed. They flee.

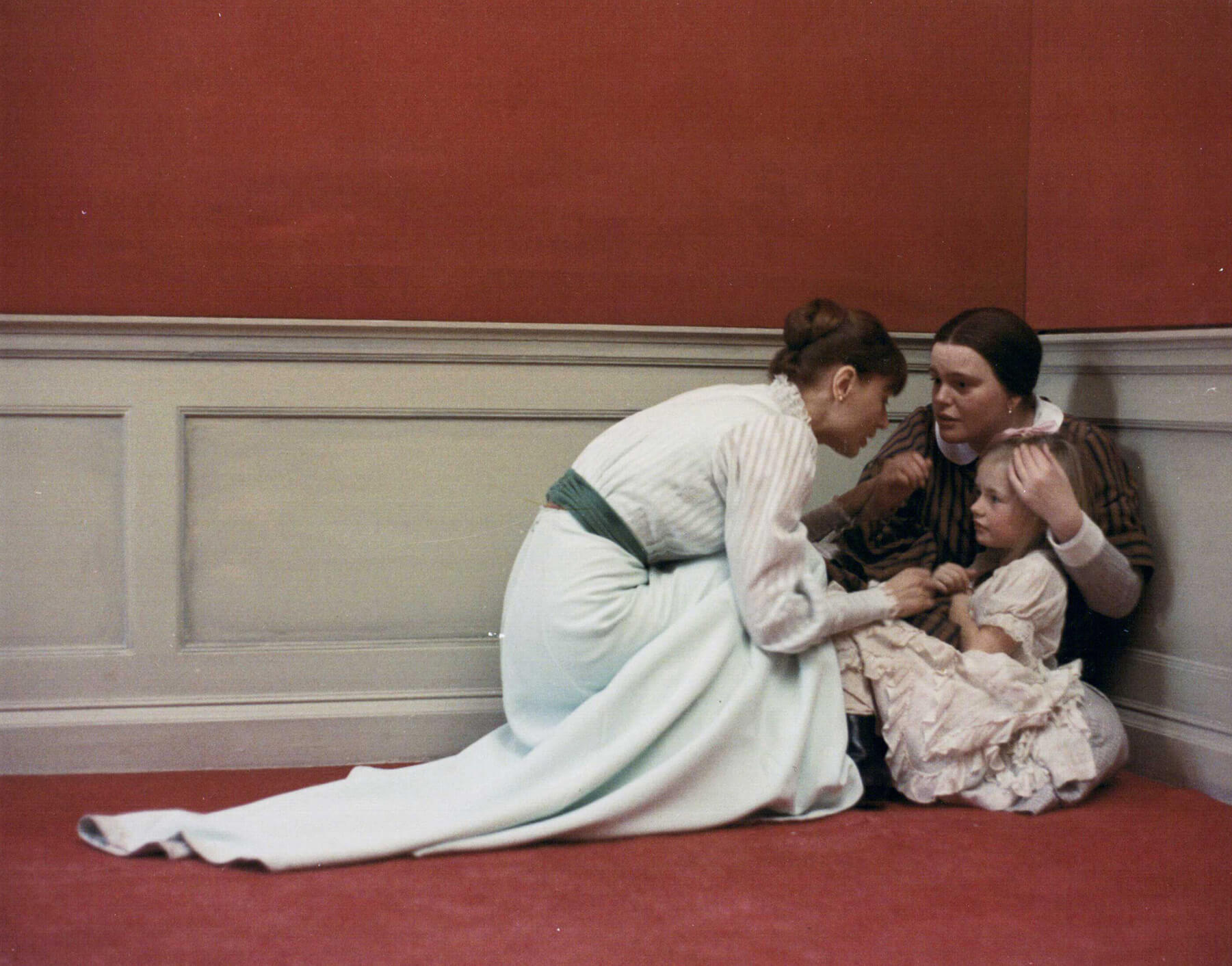

One of the most spectacular sequences in the film is played out according to the rules of dramaturgy once governed by the ‘ars moriendi’ manuals. The preparations for Agnes’s death, however, are neglected. No one opens the windows to make it easier for the dying to depart and for the agony to be lighter. Karin and Maria do not accompany their sister and do not respond to her call. They limit themselves only to the ritual washing of the deceased’s body and convening the mourners. However, the presence of a companion to the dying awaiting death was marked thanks to the figure of the servant Anna. The only person in the house who is familiar with the experience of death. Drifting in silence through the salon, she notices every new harbinger of death… she hears the howling of the wind and the crying, which heralds Agnes’s imminent departure.

The servant thus represents this particularly important symbol of human mercy and genuine compassion in Bergman’s work. The director didn’t hesitate to use the well-known metaphor of compassion, sacrifice, and redemption found in Christian art, embodied by the Pieta gesture holding the body of dead Christ. Half-naked Anna holds in a gesture of compassion the body of a dying woman abandoned even in life. For this brief moment, Anna takes the place of Agnes’s absent mother in life. At this moment, the women unite in suffering. The servant is initiated into the dimensions of these two worlds. She stands on the threshold and calls the sisters one by one to the deceased. She speaks to them in Agnes’s words. The sisters, shaken, thrown out of the established dialectics of life and death, now resemble mournful puppets, their heartlessness mercilessly exposed. But Maria and Karin do not seize their chance for reconciliation and will forever remain strangers to each other. The distance and mutual endurance of their silent presence become unbearable. The redness of the salon consumes the chalky pallor of the deceased. The air is lacking. What else binds them? The duty of mourning.

In addition to the elegiac tale of the degradation of human bonds, the protagonist of this film becomes primarily color. Red recurs multiple times as a principle of plot composition (numerous transitions to red preceding retrospections triggered by the heroines’ memories or dreams), a color component serving the characterization of the heroines (mainly to emphasize Maria’s emanating eroticism), their psychological states, or the mood of interiors. Reminiscences of this color also evoke blood (as a consequence of bodily mutilation), wine (the shattering of a glass), and an apple – being clear Christian symbols.

Black is a sign of mourning, both of spiritual deadness (the balanced, introverted Karin and the pastor losing faith in God) and of the body. Black also characterizes men in Bergman’s film. They are the heads of their families and at the same time victims of their calculating wives (Maria’s husband’s suicide attempt). They stand guard over earthly law and order (Karin’s husband giving orders or Dr. David diagnosing a terminal illness) and divine (the Protestant pastor), but the sisters’ conflict does not directly concern them. They show adaptive tendencies and reduce the experience of death to a prosaic dimension. They do not gain access to the mysterious initiatory ritual. These colors, combined with white, constitute the canonical triad for the photographic layer of the film. The expansion of these colors, which impose their presence in almost every shot, helped create a mood of unreality in the film; to create the tragic dimension of life in the “dollhouse” where true feelings were lacking.

The sparing use of the color palette in Bergman’s film also corresponds to the extremely modest musical setting. It might seem that there are only two pieces: Chopin’s A minor Mazurka and Bach’s C minor Suite. In addition to them, there is an isolated sound of cymbals, imitating clock strikes. Chopin’s Mazurka accompanies the images of the silent Agnes, wandering alone through the salon, the conventional behaviors of the other sisters during hygienic procedures; it also evokes memories of the three women’s mother. Bach’s Suite plays a decisive role in characterizing the changing relationships of the two remaining sisters. It replaces the tender words unexpectedly bestowed by the heroines.

The moment of tenderness lasts too briefly. It is a dramatic reaction to Agnes’s death. The sisters come closer to each other in a sense of emotional emptiness brought to their attention by their sister’s death. The hard shell of cynicism and calculated diplomacy cracks for a moment. Suppressed emotions or emotions twisted by forgetfulness burst out. No words are heard, only accelerating music. Mouths whisper streams of words violently. These are lies that soothe fear. Karin and Maria shake off this “moment of weakness,” embarrassed by their nudity and strangeness to each other. They try to burden each other with guilt for this moment of indiscretion. Hypocrisy hiding behind morning politeness stings the eyes like choking smoke. Anna, the only refuge of human mercy in the house, is repaid like a poor servant. Reconciliation did not come. “…and the whispers and cries fell silent.”