WILD STRAWBERRIES. Bergman’s poignant masterpiece

It was the year 1957, late spring. The paths of the director’s life were tangled into a veritable Gordian knot. On one hand, the Swede’s career had never been better. Over the years 1956/1957, Bergman significantly strengthened his position at the main theater in Malmö, which he had been leading since 1952. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Erik XIV, and Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, which premiered on March 8, 1957, proved to be significant artistic and commercial successes. During this period, one could not speak of Swedish theater without Bergman, who, in a sense, set the tone. Since 1953 and the premiere of Summer with Monika, Sweden had also become a recognizable name in the international film scene. However, it was the first half of 1957, dominated by The Seventh Seal, that solidified his name in the minds of cinephiles and critics interested in art cinema. Wild Strawberries

The frantic pace of work could not but affect the director’s health and private life. Right after the theatrical debut of Peer Gynt, Bergman had to lay down in a hospital bed. Under the observation of his friend, Dr. Sture Helander, he tried to cope with nervous problems that significantly affected his overall health (the director suffered from painful digestive issues). Work stress was certainly one of the factors that contributed to the development of the director’s illness, and his personal life did not bring relief to his frayed nerves. In the spring of 1957, Bergman’s third marriage practically ceased to exist. The Swede recalled wondering how it was possible to love someone but not be able to make a life together. At the same time, the fire ignited around 1954 between him and Bibi Andersson was slowly burning out. The romance turned out to be just a fleeting episode in the lives of the director and the actress. Numerous attempts at reconciliation between Bergman and his parents were also burning out. Despite his mother’s diplomatic behavior, his conflict with his conservative father would simmer for several more years. The young director’s opposition to Lutheran values was not tolerated by his father, a pastor. On the other hand, the son felt disgust towards the stubbornness and emotional coldness emanating from the clergyman.

It was in this mood that Wild Strawberries was born. Written in a hospital bed, the screenplay immediately gained recognition from Bergman’s producer, Carl Anders Dymling. Despite lean times for the Swedish film industry, the funds needed to produce this intimate story were quickly secured. Casting and the film’s production process also proceeded at lightning speed. Filming took place from mid-July to August 27, 1957. Immediately after completing the shoot, Bergman threw himself back into work, almost immediately heading to Malmö to prepare for the premiere of Molière’s The Misanthrope. Years later, when, in order to summarize his own work, the director watched Wild Strawberries together with Lasse Bergström, his friend and a prominent Swedish film critic, and then recorded an almost four-hour conversation about the film, it turned out that the creator said almost nothing about the period of the film’s production. All attempts to recall details from the set, the stories behind the filming of specific scenes, ended in failure. This short summer month of 1957 spilled through the recesses of Bergman’s memory to such an extent that returning to the source became impossible. This is reflected, for example, in the circumstances surrounding the casting of the legendary Scandinavian cinema figure, Victor Sjöström, in the leading role of Isak Borg. Depending on the interview, Bergman claims that already at the first sign on the blank slate of the Wild Strawberries script, he knew that the role of Professor Isak Borg had to be played by Sjöström. Alternatively, he recalls that it was not without difficulty that he was persuaded to make this casting decision by the film’s producer, Carl Anders Dymling.

Regardless of the events that led to Victor Sjöström’s involvement in the film, it is grateful that things turned out as they did. A director who began his adventure with cinema in the silent film era, the author of one of the fundamental films for the establishment of Scandinavian cinema – The Phantom Carriage from 1921 – was approaching his seventy-ninth year of life. Allegedly, he was initially reluctant to accept Dymling and Bergman’s proposal because old age was not treating him kindly. His reflective nature plunged him into a melancholy and misanthropic mood, and his body refused to cooperate at every step. The rigors of the shoot could have been unbearable for him. During conversations with Sjöström, Dymling allegedly convinced him that he did not have to worry about being pushed too hard. According to the producer, his main, and in fact only, task was to sit on the strawberry meadow and reminisce about the past. Of course, this is a massive simplification.

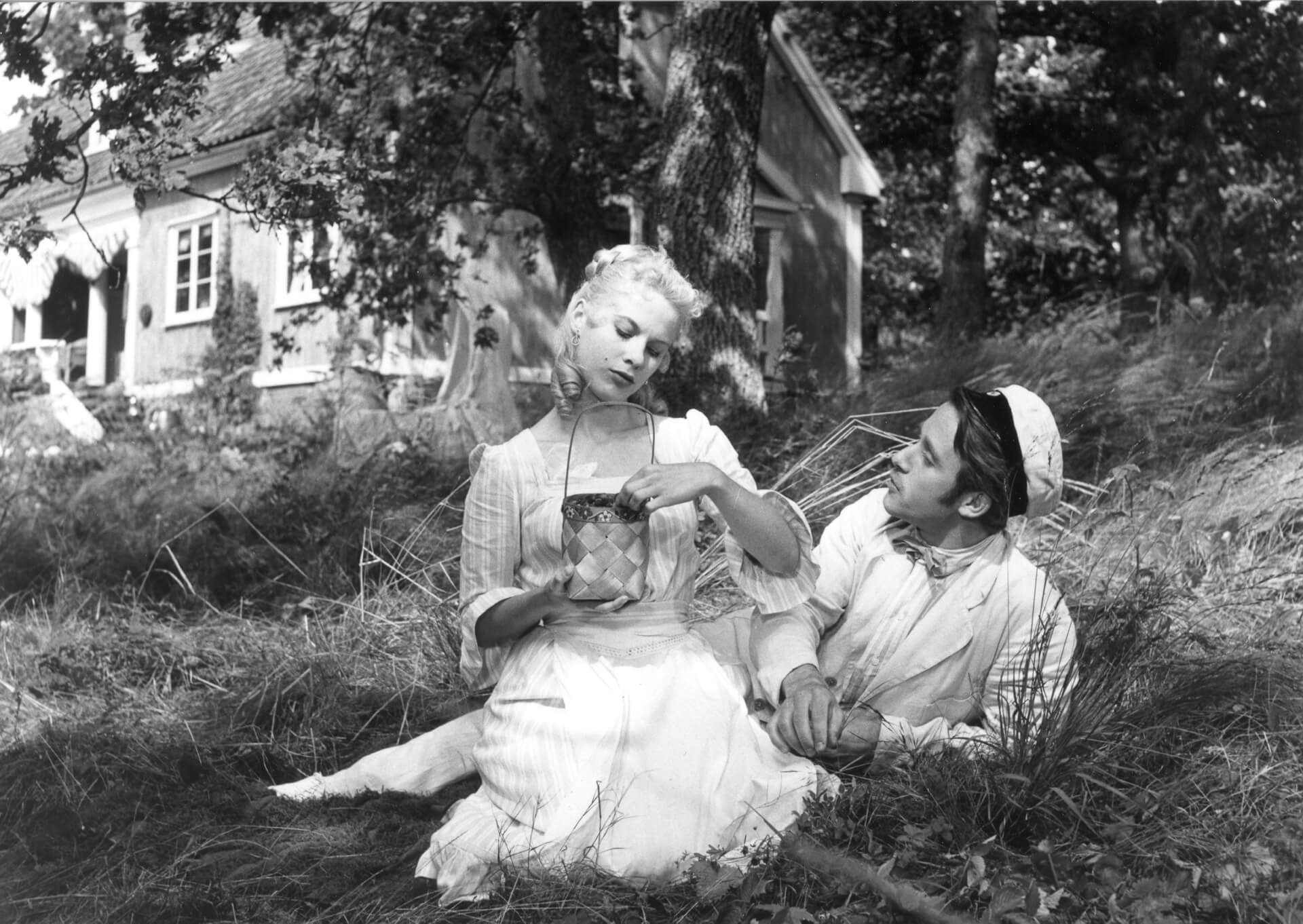

The weight of Wild Strawberries lies precisely on Sjöström’s shoulders, who bid farewell to both cinema (this being his last encounter with the medium) and life – the ailing Sjöström died two years after the film’s premiere. Bergman claims that Wild Strawberries is equally his own film and that of his master, who almost completely lost himself in the role of Isak Borg. The poignant truth hidden behind his gaze, full of pain but also hope, fixed on the strawberry bushes growing on a small meadow, had the power to change not only the history of cinema but also culture. In Nordic iconography, the strawberry field symbolized virginity, to which Bergman directly refers when revisiting the innocence of Professor Borg through it. After the film’s premiere, it acquired the power of Proust’s madeleine, an object/place that almost magically reveals the past in its full glory – as if it were right here, right now. It seems impossible, yet upon deeper reflection, entirely logical; after all, the past does not reside among the leaves of the strawberry bushes but inside the person who gazes upon them.

In Search of Lost Time

In Wild Strawberries, one cannot fail to notice the inspiration drawn from Sjöström’s aforementioned The Phantom Carriage, the most important film of his career. In the silent masterpiece, an alcoholic falls asleep on New Year’s Eve in a cemetery. He is awakened from his sleep by the titular phantom carriage, a figure from Swedish folklore responsible for transporting the souls of the deceased to the other side. Faced with death, the protagonist reflects on his own life and sees the destructive impact of his addiction on the lives of those close to him. Whether the encounter with the Scandinavian Charon is just a drunken vision, a hallucination, or a paranormal experience – the alcoholic decides to mend his ways and reconnect with the people for whom his life mattered. The key elements of this story are introspection and the subsequent examination of one’s own past, as well as the closeness of death as a catalyst for a reflective assessment of the protagonist’s life. Additionally, the pivotal point of conscience and the transformation that follows is a vision that transcends the bounds of rational understanding. In Wild Strawberries, we encounter a very similar structure, enriched by Bergman with entirely new elements entangled in a formal-narrative Gordian knot reminiscent of the one I mentioned in the context of the director’s life in the late fifties.

Regarding the role played by the strawberry bushes in the film, it is justified to refer to the philosophical concept of the rhizome introduced into the humanities by postmodernists. Boring with definitions is of course pointless; in this case, it’s about the metaphor’s resilience. We could assume that Wild Strawberries is a cinematic labyrinth, wandering through it in search of meanings. Such an approach is not entirely incorrect, although not entirely precise. A labyrinth implies a certain order, has an entrance and an exit, does not evolve, but is a finite puzzle that loses much of its complexity and mystery once solved. The rhizome, on the other hand, is wild, constantly changing, and does not necessarily have a beginning or an end. It is the perfect metaphor for the construction of Wild Strawberries and the film’s main theme, human memory, whose roots multiply and intertwine over the years, coalescing into impossible-to-unravel knots that block the life-giving water and lead to the death of some memories while nurturing others.

Bergman’s narrative simplicity is merely a juggler’s trick. It’s like saying life is simple because it always begins with birth and ends with death. Professor Borg’s journey indeed has a beginning and an end; the same can be cautiously said about the transformation he undergoes during the journey from Stockholm to Lund. However, what happened between these two points defies interpretation because life cannot be encapsulated in words. In a sense, this is what this film is about. If we gave a pen and a piece of paper to each character and asked them to write a note about Borg, many of them would be vastly different. His son would describe him as a cold taskmaster questioning his fatherhood, Marianna as a lost old man who, under the guise of pride and unshakeable principles, tries to hide his fear of death, the gas station owner would make a hero out of him, to whom he owes his child’s life, his university colleagues would honor him as a perfect scientist, and the young people he meets on the road would probably see him as a friendly grandfather and a wise man. Moreover, each of these descriptions, despite fundamental differences, would be true. This is because a person and their story cannot be encapsulated on a piece of paper like a technical drawing. To some extent, each of us is the sum of encounters with another person. It is thanks to them that new rhizomes arise, making us immortal as long as someone remembers us.

It is probably not death itself, but the realization of this fact that terrifies Borg so much. When, in the first dream vision, the professor wanders through an unknown district of the city, its streets are completely empty. There is no one to be found among them. Initially, Borg is mainly occupied with clocks lacking hands. Later in the vision, he desperately tries to find a fellow human being. When he finally spots someone, despite physical limitations, he runs towards them and places his hand on their shoulder. Unfortunately, it turns out to be just a lifeless mannequin. Borg is entirely alone. Perhaps that’s why, gently stroking the leaves of the strawberry bushes, which open the meanders of memory before him and allow him to return to the past, the professor fills it with people. Figures full of life, passion, and expression, which he so much appreciated in the hitchhikers he met along the way. These are the values he himself forgot, condemning his only son, Ewald, to profound forgetfulness, as Marianne observed – balancing on the thin line between being human and a cold, emotionless mannequin from Borg’s dream.

In Borg’s situation, it is hard not to see the fate of Sjöström himself, who, like Borg, was hailed as a master of his craft during his lifetime, yet this did not prevent him from becoming isolated from people and the resulting loneliness. Bergman reportedly saw his own father in the character of Borg while writing the screenplay, a man who, adhering to strict principles acting as armor protecting him from the world, closed himself off from dialogue with his son. The hurtful Ewald carries something of Bergman himself, who likely transferred misunderstandings between himself and his father onto his own failed relationships. On the other hand, Borg himself has much in common with the director of the film – both desperately try to revive what has passed. In one interview, Bergman admitted that the idea for the Wild Strawberries screenplay came when he unexpectedly wanted to visit his grandmother’s house during a trip to his hometown of Uppsala. When he arrived, he stood near the kitchen door and imagined that when he looked beyond its frame, he would magically slip into the past and the times of his childhood. Then the creator added that this was all a lie because in reality, he lives his childhood every day, unable to free himself from it. In this light, it is not surprising that Bergman was so affected by quarrels with his father, and it becomes entirely clear and touchingly beautiful that he concluded Borg’s journey not so much with solace in the arms of his beloved Sara but with the rediscovery of his parents, who, in full agreement, bask in the rays of the summer sun, resting on the lake shore and waving communicatively towards their son standing on the threshold of death.

At first glance, Wild Strawberries, a simple story about the transformation of a bitter professor thus teems with meanings that tell us something important not only about the people who created it but also about ourselves. On the one hand, it’s an inseparable metaphor from the author’s fears and desires; on the other, it’s a universal story about a person entangled in life, and consequently – memory. It’s impossible to put it into rigid frames because such an attempt would strip it of its most valuable essence, subtly understood at the moment of looking into the teary eyes of Victor Sjöström’s parents. It’s astonishing that in the face of the end, the scent of strawberries turns out to be more significant than the power derived from assimilating thousands of scientific volumes and the memory of the family home more valuable than delving into ways to fight death. However, let’s consider whether, in departing, we would want to know the answer to any fundamental questions, or simply, humanly, grab someone’s hand.