DAVIDLYNCH.COM Decoded: A Deep Dive into David Lynch’s World

As the man and the boy approach one of the marked trees, David notices that what appears to be a healthy, entirely ordinary trunk is teeming with pilgrimages of ants and other pests, slowly destroying the plant. For Donald, it is just another normal day as a forester and biologist dealing with diseases afflicting American flora. For David, however, it is a pivotal moment in a way.

Throughout his career, the creator will repeatedly return to this seemingly insignificant instance. Dozens of his paintings, the most iconic scenes from his films, and even the scripts themselves will speak of an almost imperceptible invasion of something sinister into an apparently normal reality. The bugs crawling across the immaculately manicured lawn in the prologue of Blue Velvet, the demons lurking in the woods surrounding Twin Peaks, or the Mystery Man inexplicably infiltrating a home in Lost Highway—all of this likely finds its origin in a certain summer day when a child first encountered the imagery of disease and death. DavidLynch.com

David Lynch’s creative journey astonishingly mirrors this dynamic. Unlike many of his peers who, after establishing their reputation, lead relatively stable lives—free from the burden of securing funding for future projects—Lynch has almost always grappled with producers. Many of his ideas, most notably Ronnie Rocket, a concept for a film that has accompanied the American director since the early days of his career, ultimately ended up shelved. The difficulties in obtaining funding for his projects frequently plunged Lynch into severe anxiety and financial troubles, impacting both his mental health and family life. Applause from critics and audiences was often mingled with waves of scathing criticism and accusations of misogyny, glorification of violence, and sexual deviance.

If Lynch’s life were likened to a tree, it would undoubtedly be a mighty one, yet full of wounds covered in resin and twisted branches sprawling without any logical order. Red ants would constantly scuttle across it as well, for in the director’s world, the home—materialized as the extension of a person’s soul—is always under threat. Lurking just beyond its threshold is a force trying to infiltrate, much like Bob, feeding on the fear and despair of Twin Peaks‘ residents.

The time marked by the making of The Straight Story and Mulholland Drive stood out as one of the brighter phases in Lynch’s career. Despite the challenges associated with the production of Mulholland Drive‘s TV pilot version, things generally went the director’s way. Most importantly, both productions were met with enthusiastic reception from critics and audiences alike, which significantly improved Lynch’s standing after a challenging period following the fading excitement surrounding the release of Wild at Heart (circa 1991).

Thanks to the story of Diane Selwyn, the director left Cannes in 2001 with the Best Director Palme d’Or. The film also caught the attention of the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, earning Lynch a nomination for Best Director. On March 24, 2002, Lynch sat in the Kodak Theatre beside his fellow nominee, Robert Altman, recognized for Gosford Park. Ultimately, Ron Howard took home the golden statuette for A Beautiful Mind. After the verdict was announced, Altman reportedly leaned toward Lynch and remarked, “This is for the best.” Once again, Hollywood rewarded one of its own, while the others were invited merely to watch. What saddened Lynch the most that evening, however, wasn’t the jury’s decision but the fact that his seat was far too distant from the smoking area.

At the end of 2001, David Lynch received a call from Gilles Jacob, the general director of the Cannes Film Festival. This time, however, it wasn’t about the galloping deadlines for submitting a film but a proposal for Lynch to chair the festival jury in 2002. Initially, the American was not thrilled with the idea because—as he later recalled—he couldn’t imagine himself in the role of someone who judges the work of others. Lynch emphasized that he knew how much effort it takes to make a film and claimed he would feel uncomfortable knowing that the fates of people who had undertaken this arduous task would depend on his subjective judgment. On the other hand, Lynch had always held Cannes in high regard, so it was hard for him to refuse the man who ensured this grand festival machine came to life every year on the French Riviera. Ultimately, Lynch agreed to take on the role but stipulated that he would forgo the chairman’s double vote during deliberations. Gilles Jacob had no issue with this. That year, Roman Polanski left Cannes with the Palme d’Or for The Pianist.

Upon returning to America, Lynch found the red ants back on the tree. His daughter, Jennifer, had to undergo a complex spinal surgery because the pain from a previous car accident had worsened to the point where it significantly impacted her quality of life. The procedure turned out to be more complicated than initially anticipated by the doctors, which, in turn, affected her postoperative condition. Jennifer was bedridden for several months, and for the first few weeks, she had to practically give up any movement, as even the slightest sudden motion could result in internal injuries. Lynch was deeply affected by the situation and grew much closer to his daughter, who had treated him more as a friend than a father for most of her life. Jennifer’s critical condition also became an opportunity to reconnect with her mother and Lynch’s first wife, Peggy Lentz. Years later, Jennifer reflected that, in a way, her illness helped her regain her family.

At the end of 2002, Lynch returned to Europe once again for professional purposes. In connection with a small concert tour organized to promote the album BlueBOB, recorded by John Neff and Lynch in 2001, the director stepped into the shoes of a musician and performed at several concerts as a guitarist. Years later, Lynch recalled the tour as one of the most terrifying moments of his artistic career. The need to perform live in front of an audience was an obstacle he barely managed to overcome. According to attendees and the press, however, the concert in Paris was quite successful.

DavidLynch.com

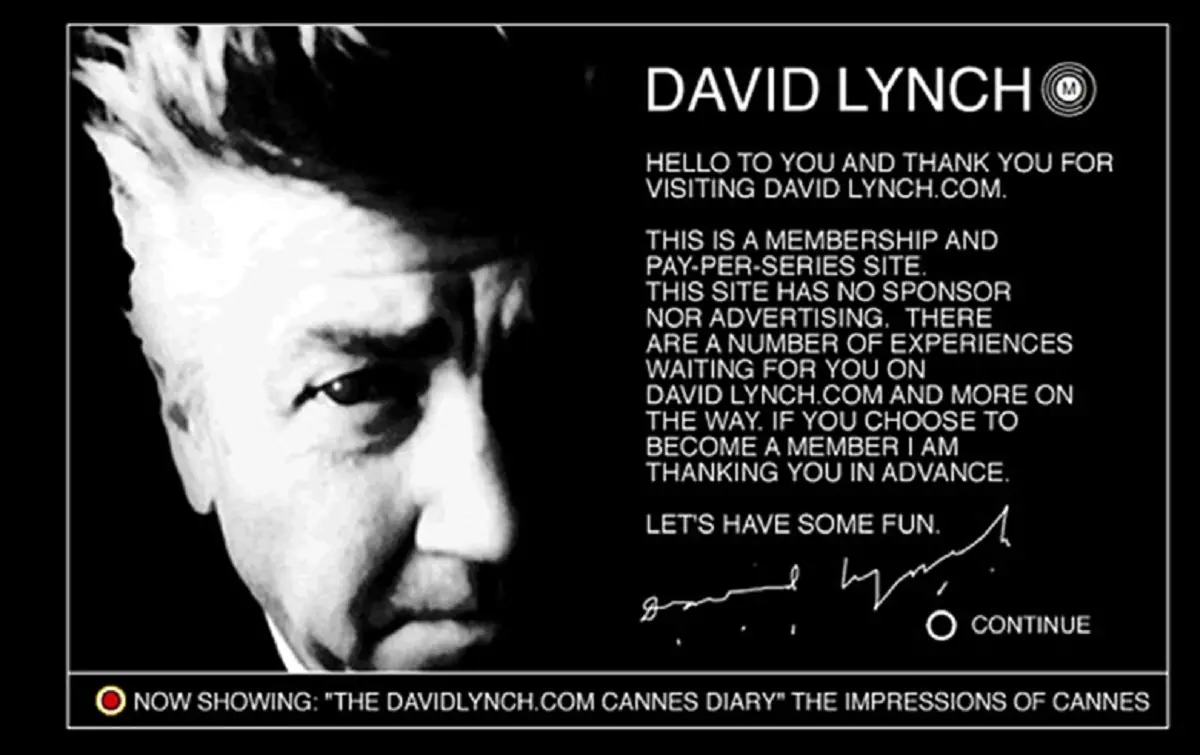

During the production of Mulholland Drive, Lynch began exploring the world of new media. While he had once firmly believed that films should be shot on film stock and experienced exclusively in a theater, the new possibilities offered by emerging platforms became more than intriguing to him. In the 1990s, the director relented and ventured into television, which he had previously regarded as a lower-quality medium. What swayed his decision was the opportunity to craft multi-hour, multi-threaded narratives that wouldn’t have been possible in theatrical film form.

The internet, however, appealed to Lynch for a slightly different reason: it had no boundaries, and the selection of material that could appear there was limited solely by the director’s creativity and imagination.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Lynch purchased a computer and the software necessary for graphic and video editing. His hard drive housed Photoshop, After Effects (for video editing), and Flash (for animation). The creator began learning to use entirely new tools. On December 10, 2001, the DavidLynch.com website was launched. The site was intended as a platform through which Lynch could share projects with the world that would (likely) otherwise have ended up in a drawer. Some of the materials on the site were available for free, but accessing more time-intensive projects required purchasing a paid subscription. Its cost was ten dollars per month. Lynch justified this solution by stating that the expenses of running the site (specialists) were so high that without the subscription, the project would very quickly fail. The site featured no advertisements apart from links to a store selling merchandise associated with the director’s world—for instance, mugs with Twin Peaks logos. As part of the paid subscription, users also had access to a chat where they could communicate with the director. Lynch, especially in 2002, was particularly active in this regard.

Over the years, the site featured numerous short, mostly experimental projects that were likely to interest only the most devoted fans of the director and scholars writing about the intersection of cinema and the internet. These included short films such as Coyote, Steps and Sunset. Each lasted no more than a few minutes. Each depicted footage recorded by a stationary camera mounted on a tripod. The titles of these short films are literal, but anyone who has ever visited Lynch’s world knows that a static shot of stairs can evoke an unease equal to that of watching a horror film. Most of these materials were recorded using semi-professional or amateur cameras, and a significant portion of the films required no intervention from the creator in his surrounding home environment. However, for some projects, to the delight of neighbors, he decided to build sets and arrange scenes. For example, in the aforementioned Coyote, following an animal moving through a room illuminated by lamp light did not actually take place inside a building. For the film, Lynch built a replica of a room outside his home and illuminated it with strong film lights for several nights, waiting for the coyote visiting his property to become accustomed to the sight and decide to enter the set.

Among the most notable projects that premiered on DavidLynch.com were Dumbland, Rabbits, Out Yonder, Darkened Room, and Cannes Diary. Starting from the end, Cannes Diary was a video diary created for the site’s subscribers, documenting David Lynch’s experience at the Cannes Film Festival in 2002. The production is particularly interesting because the director rarely shares his private life in this way, and his enthusiasm in recounting the events on the French Riviera reflects the fascination he felt at the time for the internet and the group of people from around the world gathered around his website. Darkened Room is a video just over eight minutes long, reminiscent of short forms created by Lynch during his work on Eraserhead (e.g., The Amputee from 1973). Out Yonder is a series of black-and-white films in which the director and his eldest son sit on chairs in front of a building wall. Their heads are adorned with whimsical hats, and their mouths spout more or less coherent dialogues. The conversation is occasionally interrupted by unexpected events, such as a visit from a giant neighbor who dropped by to borrow some milk.The most interesting are undoubtedly Rabbits and Dumbland.

Rabbits is an unconventional variation on the sitcom format. Throughout the series, the camera remains fixed, offering a constant view of a green room. The protagonists are the titular rabbits—Jane, Suzie, and Jack. The characters are human-sized and, aside from their rabbit heads, look completely human. Under the animal masks are Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, and Scott Coffey, actors who had previously worked on the set of Mulholland Drive. The rabbits engage in unsettling conversations that do not form any logical continuity. Occasionally, canned laughter characteristic of American sitcoms can be heard offscreen, and sometimes the green of the room is broken by a burning wall.

In Rabbits, nothing connects into a whole; there are no puzzle pieces to piece together. However, the series manages to captivate and create tension. It is hard to shake the feeling that somewhere on the edge of the frame, beyond the threshold of the rabbits’ house, lurks a malevolent force that threatens not only them but also the viewers peering into their lives. Probably for this reason, their world found a second life in Inland Empire, which uses segments from the online series.

Dumbland, on the other hand, is Lynch’s only animation created solely using a computer. The director produced eight episodes of the series, totaling about half an hour of screen time, with Flash. Initially, the series was even supposed to land on the website of the software’s producer. The promotional project, showcasing the tool’s capabilities, was to involve several well-known directors, including David Lynch and Tim Burton. Ultimately, the company’s financial problems prevented this form of promotion, which did not bother Lynch much. He was convinced that his animation would not have appealed to the Flash advertising specialists and, as a result, would not have made it onto the software producer’s site anyway.

Dumbland presents short scenes from the life of a poor, stupid white man who struggles to control his anger. His vile temper ruins the lives of his wife and child. The series is brimming with violence, aggression, and an absurd, grotesque view of reality. Its tone is accentuated by a sloppy, simplistic drawing style, partly due to Lynch’s own vision and partly to his frustration with learning a new tool that posed far greater challenges than the familiar animator’s staples—paper and pencil. Reportedly, Lynch spent about 70–80 hours working on a single, short episode.

In hindsight, assessing the materials featured on Lynch’s now-defunct website is no easy task. Applying categories that work for discussing cinema doesn’t quite fit here, as DavidLynch.com was, in a sense, a form of an online modern art exhibition aimed at testing an entirely new medium. An undeniable value of the site was the opportunity to delve deeper into the director’s world and better understand the processes leading to the creation of his films. Ideas that occupied Lynch’s attention during this period didn’t end up in the trash or a drawer; they landed on the website, allowing fans to try to guess the direction the creator was heading in. One also can’t shake the feeling that, through the internet, Lynch finally fulfilled one of his dreams by breathing life into the paintings he created. This is evidenced mainly by the overrepresentation of static shots in the materials debuting on the website.

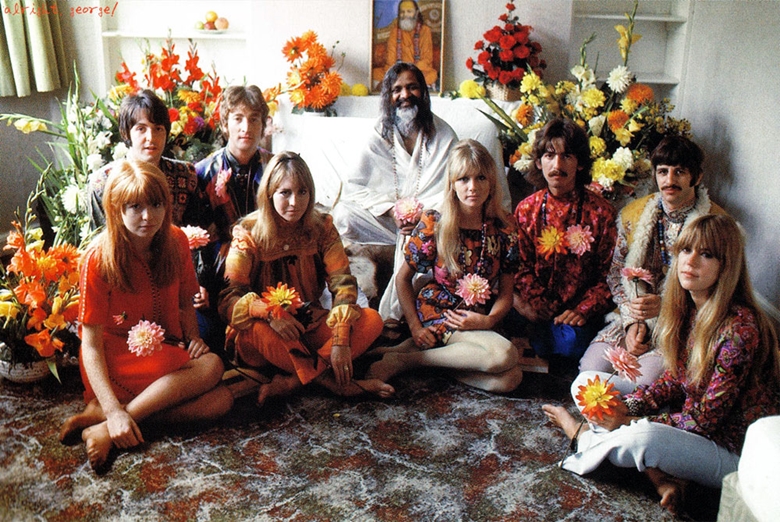

David Lynch’s fascination with meditation techniques has been ongoing since the 1970s. The director has repeatedly emphasized that without this form of work on his own body and mind, he would not only be unable to create but also to live. Lynch considers Transcendental Meditation (TM), the creation of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, to be the most effective. The guru of this movement, which extends far beyond the boundaries of perfecting meditation techniques and takes the form of a religious organization, was viewed in a highly ambivalent light during his lifetime.

Some, including Lynch, spoke of him in glowing terms, while others accused him of using his influence to make money and seduce women. The most widely discussed crack in Maharishi’s initially pristine reputation came from Mia Farrow’s accounts. She claimed that during one of her private audiences with him, he touched her in a way that clearly indicated the meditative master’s sexual intentions. Following these revelations, John Lennon, who, along with the other Beatles, had also visited the guru, wrote the song Sexy Sadie, which was a direct attack aimed at Maharishi.

In 2003, after writing the necessary check, David Lynch underwent personal training under the guidance of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. He described the time spent with the guru as a wonderful period of harmony, with only one point of disagreement: Maharishi reportedly asked Lynch to quit smoking for the sake of his body’s purity, to which the director replied that he would never give it up for the rest of his life. Following his visit to the master of Transcendental Meditation (TM), Lynch’s interest in TM-related matters took on an entirely new form. Starting in 2004, he began publicly advocating for the organization’s ideas and promoting them through all available channels. From that year on, he also started appearing at lectures and seminars dedicated to TM. In 2005, he established the David Lynch Foundation, aimed at promoting TM education in schools and raising funds to teach meditation to children and disadvantaged individuals (the official TM course costs $2,500).

In 2007, Lynch became embroiled in controversy during a TM-related event in Germany. During a speech, Emmanuel Schiffgens, a prominent TM activist, used the term “Invincible Germany.” When an audience member accused him of echoing concepts promoted by Adolf Hitler, Schiffgens replied that Hitler had failed to realize this vision. This incident also brought criticism upon Lynch. Media and the public began questioning his motives for being involved with TM. A reflection of these concerns is the controversial 2010 documentary David Wants to Fly by David Sieveking, which portrays Lynch in a decidedly negative light, suggesting that he is entirely under the influence of a movement depicted as a textbook example of a religious cult. However, the situation is more complex.

From an observer’s perspective, Lynch’s commitment to TM seems to have gone a bit too far. The impact of TM on Lynch’s creativity and life is undeniable, as seen in his somewhat grandiose book Catching the Big Fish (2007), where he discusses the connection between meditation and the creative process. The broader activities of the movement surrounding TM are a topic for a separate discussion. When it comes to Lynch, the key question revolves around his intentions and his belief in Maharishi’s philosophy as a genuine source of peace and solace. Sieveking and many of Lynch’s critics overlook these aspects, focusing instead on presenting the director as a middle-aged man beguiled by manipulative cultists.

While it is indeed unsettling to see photos of Lynch receiving awards from dubious individuals dressed in cheap imitations of Indian robes—and there is likely some truth to the critiques posed by Sieveking and others—it’s important to remember that Lynch’s fascination with TM did not start with his 2003 visit to Maharishi. Instead, it dates back to the 1970s, when Lynch lived in Philadelphia. He has often mentioned that meditation helped him survive one of the hardest periods of his life, when he feared for his family’s well-being, slept with a gun, and poured every cent he earned into the production of Eraserhead. It is unfortunate that a group of opportunists appears to be exploiting Lynch’s name and enthusiasm to profit handsomely. However, declaring that Lynch has completely lost touch with reality seems overly harsh. From an observer’s perspective, it does appear that he may have taken his devotion to TM a step too far.