WILD AT HEART Explained: Raw Emotions, Truly Unique

The comedy about a group of eccentric misfits searching for treasure hidden by a deceased millionaire cost Dino De Laurentiis’s studio around ten million dollars. The profits it generated didn’t even cover 10% of the film’s production budget. The small studio, which had been struggling to realize the American dream of the Italian producer, couldn’t handle the blow. Money Mania became the nail in the coffin for De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, which had faced constant financial challenges since its inception.

Starting in 1988, the studio ceased operations, and the rights to the scripts it had purchased and films that were in early production stages (like Total Recall) were put on the market and sold off to other players in this tough industry. The same fate befell David Lynch’s scripts—Ronnie Rocket and One Saliva Bubble. Due to his particular attachment to the former, Lynch didn’t want his idea to fall into the wrong hands and be realized without his involvement. This is why he left the editing room, where he had been working on the post-production of the first season of Twin Peaks, and began knocking on doors to regain the rights to his ideas. Looking back, we know that neither the story about a dwarf who becomes a rock star through an electric impulse, nor the madcap series about personality swaps, were ever made. Thus, by the end of 1989, Lynch had achieved a small victory—he prevented his ideas from being realized without his participation, though he wasn’t able to convince producers to fund them. Wild at Heart.

However, the last months of 1989 were especially intense for Lynch due to other commitments. The premiere of Twin Peaks was fast approaching, and the series was getting its final polish in the quiet editing rooms provided by ABC. Meanwhile, Propaganda Films, the studio with which Lynch had signed a contract for his next feature, had assigned him to work on the adaptation of a little-known 1940s noir novel. Lynch was about to begin the process of creating a screenplay when Monty Montgomery, one of the producers of Twin Peaks, entered the editing room where Lynch was working on the pilot. Montgomery brought a novel and asked Lynch to read it and consider working as a production supervisor if Montgomery could secure the rights to direct the film. The Twin Peaks creator smiled at the producer and asked what would happen if he liked the book so much that he decided to direct it himself. Montgomery replied that if it went that way, he wouldn’t mind. Lynch received an incomplete version of Barry Gifford’s Wild at Heart, missing the last two chapters, which were still in preparation. Lynch devoured the story of Sailor and Lula almost immediately. The author’s style greatly appealed to him, as did his fascinations and his way of looking at the world. Greg Olson points out that the main character of Blue Velvet, Jeffrey Beaumont, sums up the events in the film with words that are emblematic of Lynch’s entire body of work: ‘It’s a strange world.’ In Gifford’s novel, the characters say that ‘the world is wild at heart and weird on top.’ Is there anything more to say?

Immediately after reading Gifford’s book, Lynch contacted Montgomery to inform him that he wanted to make a film based on it. According to their agreement, the Twin Peaks producer dropped his own plans and allowed the text to be taken over by the American director. Montgomery even helped to persuade the people at Propaganda Films to remove Lynch from the project involving the noir adaptation and let him make an adaptation of Gifford’s prose instead. Once he got the green light from the people holding the money, Lynch contacted Gifford himself, who was enthusiastic about the news that Lynch would be working on a film based on his latest story. Gifford, known for exploring American subcultures far from the glitz of Beverly Hills, and recognized for his portrayal of the world of dirty streets and shady characters, even said that after watching Blue Velvet, he was surprised, stating that even he couldn’t come up with such a strange and perverse story. Considering that Lynch grew up in an almost idyllic environment of smiling neighbors and loving parents in a perfect 1950s home, while Gifford was the son of a local gangster who was a friend of Bugsy Siegel and Miss Texas, spending his childhood in Chicago hotel rooms, this is quite a thought-provoking statement. Despite their differing backgrounds, the two men got along very well before and after the creation of the film version of Wild at Heart. Even though Lynch made significant changes to the original novel, Gifford fully accepted his vision and often emphasized in interviews how pleased he was that alongside his Wild at Heart, Lynch’s version also existed.

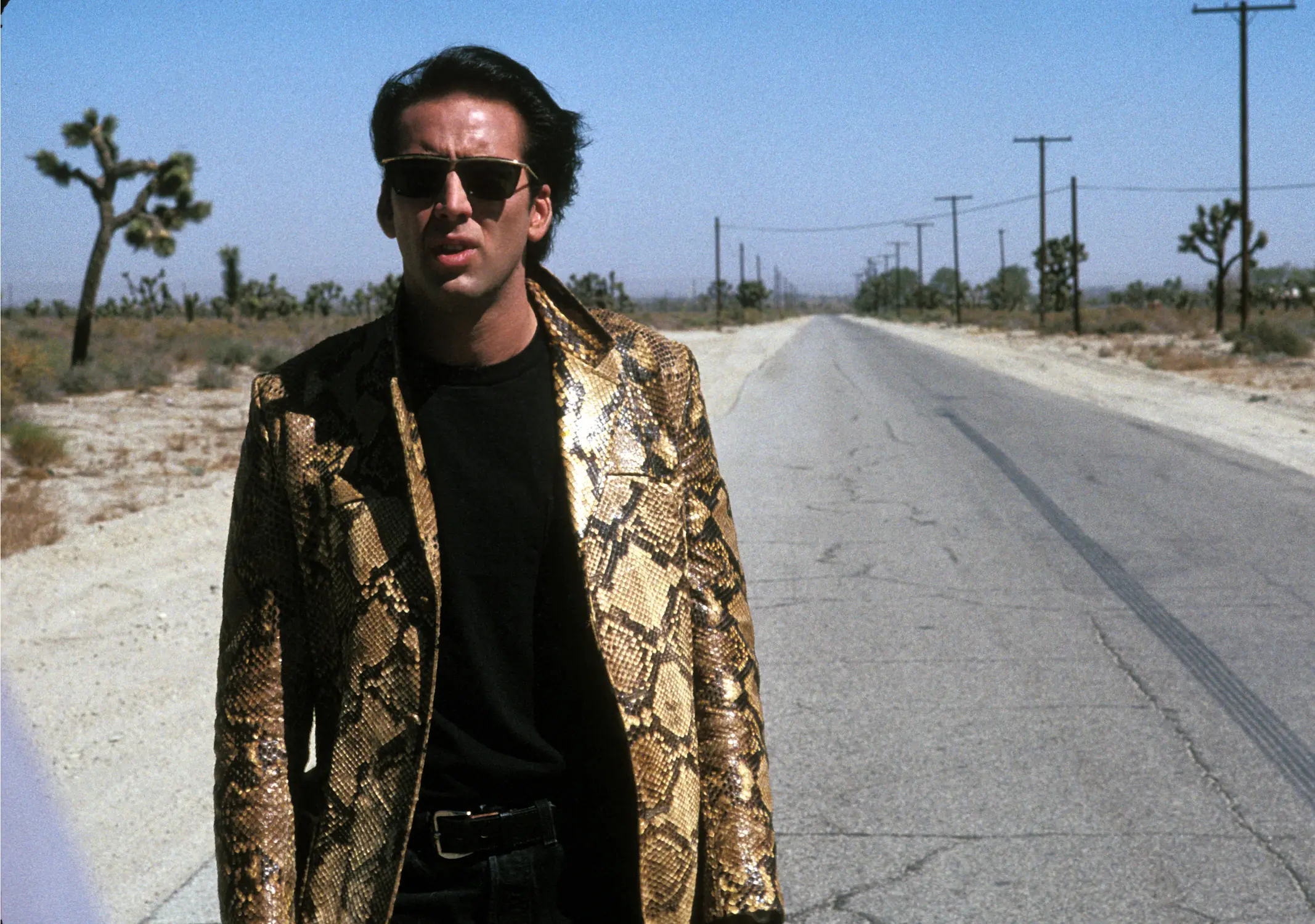

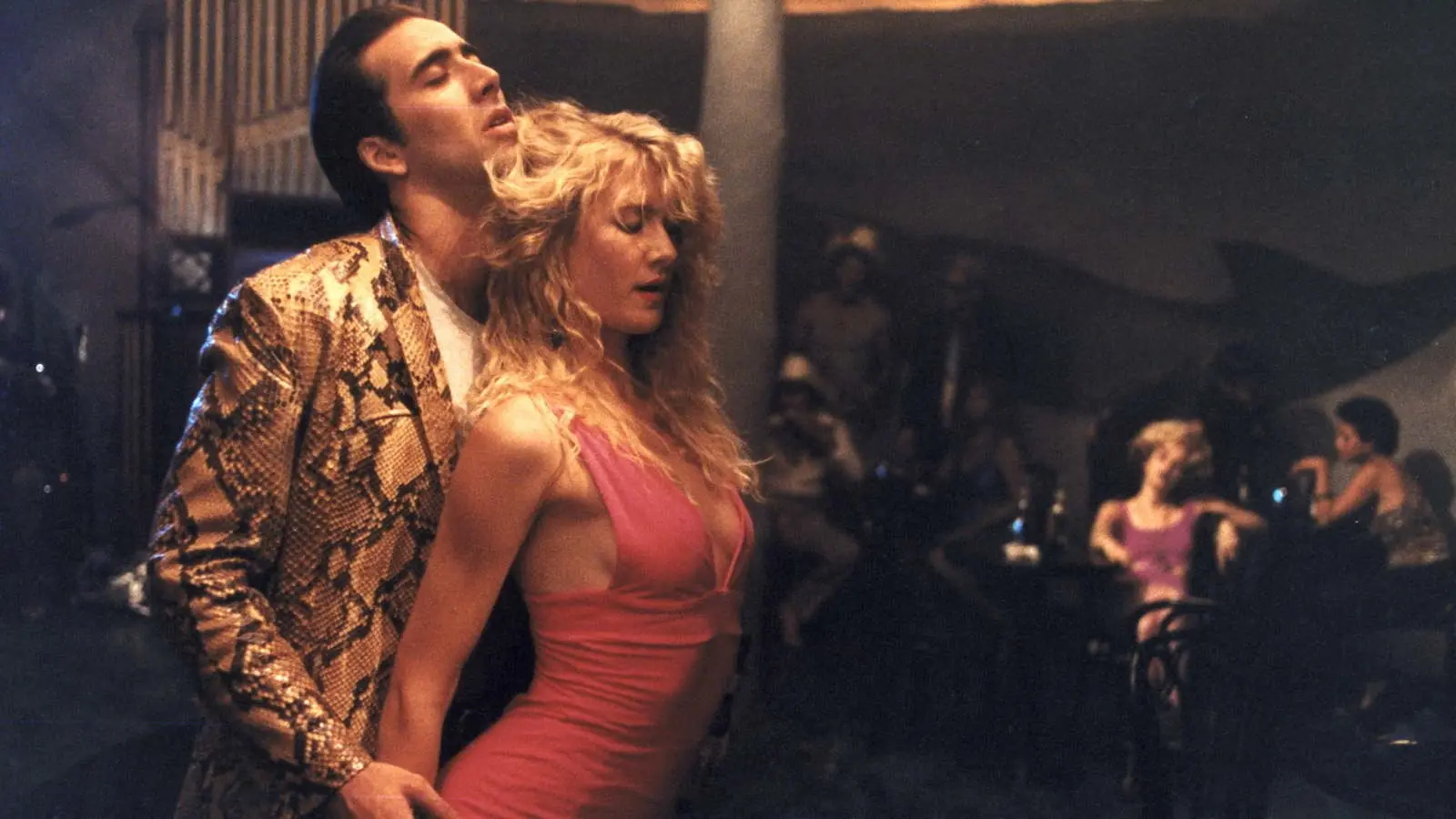

The first draft of the screenplay was written in just a week. Lynch was completely absorbed in the world Gifford had created, but he quickly began to see opportunities to develop the material in such a way that the adaptation could become a more personal, auteur project. Even at the early stage of writing the script, the idea emerged to weave loose connections between Wild at Heart and one of Lynch’s favorite films—Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz. Lynch saw parallels between the two stories, emphasizing that both were about a journey through a strange, even insane world. Additionally, Dorothy’s somewhat naive ideals suited Lynch’s vision of Lula’s worldview. According to Lynch, Lula’s sexual aggressiveness and freedom were just one very important part of her character. The second part brought her closer to a child who looks at the world with wonder and, like Jeffrey Beaumont, marvels at its strangeness. Sailor automatically reminded Lynch of one of his childhood heroes—Elvis Presley. Lula, on the other hand, was to resemble Marilyn Monroe, whose story had recently inspired the creation of the mysterious world of Twin Peaks. One could say that Lynch entered the 1990s hand-in-hand with icons from his childhood. Finally, the director decided to deepen the characters, add several new ones (most of the eccentric cast that parades through Wild at Heart), and change the ending. In Gifford’s version, the ending is rather bitter—Sailor leaves Lula, and their love doesn’t survive the trial they’ve been put through. Lynch hated this ending and completely disagreed with the idea that such a strong, almost primal bond between the characters could be broken. Hence, the magical ending, full of Presley and The Wizard of Oz.

Fire on Beverly Boulevard

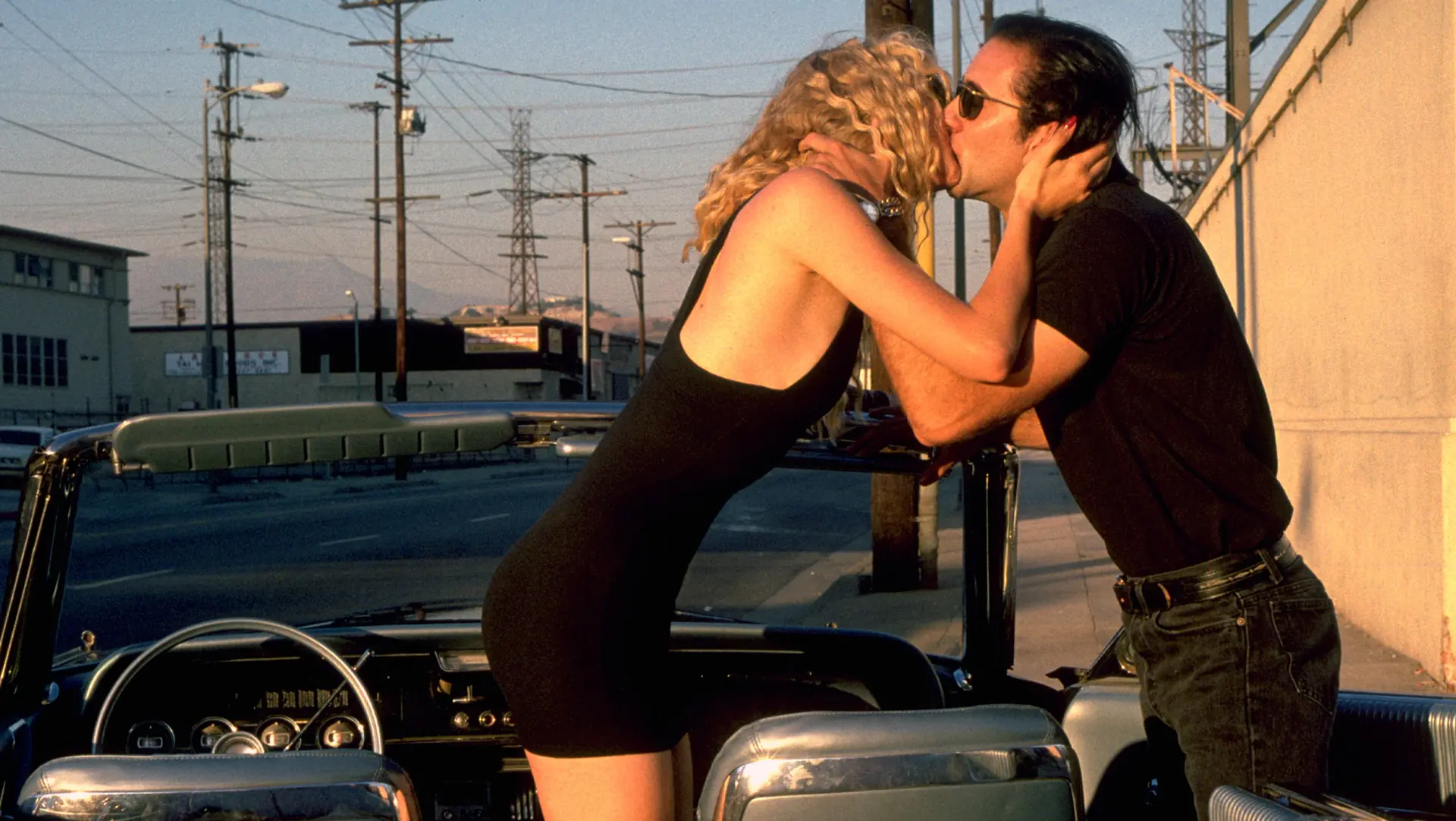

Lynch immediately envisioned Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern for the roles of Sailor and Lula. Cage’s roles throughout the 1980s, particularly in Norman Jewison’s Moonstruck, convinced Lynch that Cage was the right choice for Sailor. In one scene, Cage’s character delivers a passionate monologue about the nature of love—this confirmed for Lynch that he had found his Sailor. The situation with Laura Dern was a bit different. After Blue Velvet was completed, the young actress and the director became close friends. Dern would often visit Lynch at his home, sharing black coffee and music. On the surface, the role of Sandy in Blue Velvet, an innocent girl, seemed nothing like Lula, a sexy, high-energy character created by Gifford. Yet Lynch quickly realized that at some mysterious level, the two characters were quite similar. Sandy, an American princess dressed in frills and living in a pink room, believed in the power of love, just like Lula. Sandy’s faith in love is symbolized at the end of Blue Velvet by the robins that eat the insects crawling among the perfect green grass. Likewise, Lula’s deep belief in love and its transformative power was essential to her character. Underneath the makeup and sexual aggressiveness, Lula was a dreamer, much like Sandy, the girl from the pink room. That’s why Lynch decided that Laura Dern should play Lula in Wild at Heart. The actress didn’t hesitate for a moment, even though she knew that, because of Lula’s behavior, she would have to break many of the boundaries she had never approached on screen before.

The tension on-screen was heightened by Lynch’s decision to cast Diane Ladd—Laura Dern’s real mother—as Lula’s controlling mother, who tries to dominate her daughter’s life and destroy Sailor. By the time of filming, the two women had become good friends, as Laura’s rebellious phase had come to an end. However, just a few years earlier, Ladd and her daughter had had a significant conflict, primarily because Laura had decided to enter adulthood much faster than her mother would have liked. Some of the issues between Dern and Ladd during Laura’s adolescence had been worked through on the set of Joyce Chopra’s Smooth Talk, which tells the story of a fifteen-year-old girl who, during summer vacation, meets an older man and—against the will of her family—gets involved in a relationship. Wild at Heart, on the other hand, could be seen as a grotesque hyperbolization of the relationship between Dern and Ladd during Laura’s teenage years. It’s worth mentioning that Diane Ladd became pregnant with Laura while filming Roger Corman’s road movie The Wild Angels. She met Bruce Dern, Laura’s father, during a theater production of Tennessee Williams’ Orpheus Descending (Williams was a cousin of Ladd’s). So one might wonder whether, during the making of Wild at Heart, Ladd sometimes looked at her daughter with slight apprehension, wondering if she might follow in her footsteps and make her a grandmother.

It’s possible that there were reasons for such concerns. Lynch fondly recalls that during the first meeting he arranged for Cage and Dern, a massive fire broke out near the restaurant they were at, burning down the Cinematheque complex on Beverly Boulevard. Considering how important fire is in Wild at Heart, representing both Lula and Sailor’s passion and the destructive force that could ruin their relationship, this was quite an extraordinary coincidence. Additionally, before filming began, Dern and Cage took a road trip together to Las Vegas to bond and prepare for the film’s more intimate scenes. They packed a car full of candy, courtesy of Dern, lost money in casinos, and had a few drinks. After returning, Dern said that as they were nearing home, surrounded by candy wrappers and the smell of sun-baked skin, she knew exactly how Wild at Heart should feel.

Leaving Twin Peaks

The production of Wild at Heart was incredibly fast-paced. Even while the screenplay was being written, the producers were finalizing the organization of filming locations and gathering the necessary equipment. Lynch started shooting immediately after completing post-production on the first season of Twin Peaks, and as he recalls, he had the finished film ready before ABC even aired the fourth episode of his cult TV series, which was on April 26, 1990. Due to his intense focus on Wild at Heart, Lynch almost entirely distanced himself from the making of the second season of Twin Peaks, something he later regretted. However, in hindsight, he concluded that he wouldn’t have passed up the opportunity to adapt Gifford’s work for the sake of keeping close control over what was happening in the small TV town near the Canadian border.

Despite the rapid pace of the work, there were some issues on set. One of the biggest challenges was Laura Dern’s initial inability to fully embody the fierce, sexually charged Lula. The solution turned out to be chewing gum. Lynch noticed that when Dern was chewing gum to relieve stress, her expressions matched exactly how Lynch envisioned Lula. As a result, in many key scenes, Lula indulges in this habit. Another major problem involved the scenes requiring the use of camera-equipped vehicles. Lynch recalls that setting them up took hours. One day, he arrived on set at six in the morning, but it wasn’t until three in the afternoon that he could start shooting, which drove him mad. Throughout the filming, Lynch tried to convince the producers that he didn’t need the fancy safety measures to prevent him from falling off a moving vehicle. He suggested that they simply tie him to the car instead. The producers refused, fearing the consequences from insurers in case Lynch’s bindings failed.

Out of respect for Gifford, the director invited him to the set and showed him some scenes that had been filmed before his arrival. The author suggested a few ideas that eventually made their way into the movie, though from the moment he stepped into the studio, Gifford made it clear that he wasn’t an oracle and didn’t want to interfere in the final shape of the film, trusting the crew and their vision for Sailor and Lula’s story.

Industrial Symphony

Despite the sprint-like pace of Wild at Heart, during the shoot, Lynch also took on the preparation of a stage project titled Industrial Symphony No. 1: The Dream of the Brokenhearted. It was created as part of the annual Brooklyn Academy of Music event. In addition to Lynch, Angelo Badalamenti was responsible for creating the performance. The show was first performed on November 10, 1989, before the premieres of Wild at Heart and Twin Peaks. Lynch admits that due to the limited time, he and Badalamenti decided to use elements they already had, which is why the performance was built around songs by Julee Cruise. Michael J. Anderson appeared in it as The Man From Another Place (from Twin Peaks), and for the purpose of the show, Cage and Dern recorded a telephone conversation while they were working on Wild at Heart.

This was Lynch’s first stage production, so during its creation, many issues arose from his unfamiliarity with the workflow typical of a theater set. The lack of sufficient rehearsal time led to some parts of the performance taking on a life of their own. There were also technical problems—first with the lighting, which was intentionally dim but was eventually brightened for the video crew, and then with the sound, which had to be broadcast from two amateur cassette players connected to massive stage speakers. During the show, a man on nearly five-meter stilts, encased in a deerskin costume attached to medical stretchers, collapsed from lack of oxygen, heat from the incandescent lamps, and his awkward position. He fell toward the orchestra section but was saved by a musician, averting what could have been a serious accident. For subsequent performances, they stopped shining lamps directly on the performer, and he was stationed next to a large water tank so that, if necessary, he could fall into it rather than onto the stage.

Industrial Symphony No. 1 is particularly interesting in the context of Wild at Heart, as the story it tells could be seen as an alternative ending to Sailor and Lula’s story, more in line with Gifford’s novel. The plot revolves around a girl lamenting after a phone call in which her boyfriend tells her he’s leaving. Since the girl is played by Dern and the boy is voiced by Cage, it’s easy to interpret the performance as a kind of alternate ending to Wild at Heart, one that aligns more with Gifford’s original conclusion. It’s an experiment worth seeing, where the worlds of Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart collide, even before the TV series aired or the film hit cinemas worldwide.

Coffee and Cherry Pie on the French Riviera

The rapid production of Wild at Heart allowed it to qualify for the main competition at the 43rd Cannes Film Festival. Lynch would be competing for the Palme d’Or against the likes of Fellini, Godard, Tornatore, Eastwood, Zhang Yimou, Ken Loach, Alan Parker, and Ryszard Bugajski with his Interrogation. Lynch, always a bit eccentric, decided not to send the film in the traditional way but to personally deliver it to the French Riviera. Once in France, he wasn’t sure about his skills as a courier, so he asked the festival organizers to let him watch the film in one of the screening rooms to ensure everything was in order with the tape. The screening, which began around 1:30 AM, was attended by Lynch’s then-partner Isabella Rossellini, critic Gene Siskel and his wife, and Barry Gifford. Before the film began, Lynch asked Gifford to give him an honest opinion afterward. About eighty minutes into the film, Siskel’s wife left the room, unable to bear the violent scenes. When the lights came up nearly an hour later, Gifford leaned toward Lynch and uttered just one word—‘Blowtorch.’ Given the temperature a blowtorch reaches and the recurring fire motif throughout Wild at Heart, it’s safe to assume that Gifford was more than pleased.

At the festival, Lynch felt at home in France. Wild at Heart was received with enthusiasm, though, as always, there were voices of criticism. Additionally, every Thursday near the Palais des Festivals, they organized Twin Peaks Thursdays, where episodes of the series, airing for the first time on ABC, were screened. People who gathered around the red carpet were served hot black coffee and cherry pies. The only thing missing was the sound of Douglas firs. The jury, led by Bernardo Bertolucci, was kind to Lynch. To the dismay of Roger Ebert, who reportedly booed and hissed during the awards announcement, Wild at Heart left the French Riviera with the Palme d’Or. The festival dinner that followed went down in history when Nicolas Cage, sitting near the wife of Gilles Jacob, the Cannes Film Festival director, jumped onto the table and, like Sailor, sang Love Me Tender by Elvis Presley.

It’s a Strange World

Wild at Heart occupies a unique position on Lynch’s cinematic map. It contains a lot of the elements characteristic of Lynch’s work, but the way the story is told represents a significant departure from his other productions. The film’s world is constructed with grotesque, hyperbolic elements, which appear in more subtle forms in Lynch’s other works. Lynch’s films are typically filled with strange, surreal characters who move and speak in ways that seem almost physically distorted and unnerving. Usually, such characters are rooted in the narrative, and their appearance has some deeper meaning or understandable cause. But watching Wild at Heart, one can’t shake the feeling that some of the characters exist simply to add layers of strangeness and to shock the audience. In this context, the story of Sailor and Lula can sometimes feel a bit calculated, as though it were designed to test the boundaries of the film’s audience. Yet, in between the scenes and sequences, there’s something extraordinary and deeply sincere in this film. The titular wildness of the heart is present from the first minute to the last, at times literally spilling off the screen.

In adapting Gifford’s text, Lynch emphasized that the world in which Sailor and Lula lived should be black and white. Bad people had to be truly terrifying (like the brilliant Bobby Peru!), while the good had to be almost saintly. Some might see this as an oversimplification, but it is this constant contrast between extremes—hot and cold—that creates electric cinematic tension. These dichotomies are visible throughout the film, further emphasized by the loose connection to the fairy tale structure of The Wizard of Oz. The contrasts reach their peak in two iconic scenes from the film. In the first scene, Lula and Sailor are driving down a dark road and suddenly see the wreck of a car in front of them, with a body lying on the ground. As Sailor checks what happened, a bloodied woman with an angelic face, played by Sherilyn Fenn, approaches Lula. The left side of her skull is crushed, her brain malfunctioning, but she frantically searches for the purse she lost in the accident, unaware that she is dying. Lula and Sailor, however, know that the woman’s life is fading away and that they are witnessing her final moments.

The second scene is a direct contrast—a celebration of life. Sailor is asleep in the back seat of the car, which is speeding down a sunlit road. Lula listens to the radio, switching through stations filled with news about escalating violence, perversions, and rapes. Overwhelmed, she pulls the car over, runs to the side of the road, and screams at Sailor to find her some music. When they find a station playing Powermad’s high-energy guitar music, Lula erupts into a wild frenzy of expression, releasing all her negative emotions in an ecstatic dance. Suddenly, Powermad fades out, and the aggressive music is replaced by Richard Strauss’s Im Abendrot (In the Sunset). In the literal translation, the title of this song means ‘In the Setting Sun,’ and indeed, warm sunlight bathes the lovers as they stop their frenetic dance and find peace in each other’s arms. For this brief moment, nothing else matters. This moment is one of the brightest flashes of light in the dark world of David Lynch’s imagination, and in my opinion, one of the most beautiful scenes in cinematic history.

It is in this hyperbolic approach, in this constant oscillation between kitsch and excess, that the main strength of Wild at Heart lies. The film is like a ticking time bomb, ready to explode at any moment. The emotions of the characters are palpable, mixing love with hatred, fear with hope, aggression with compassion. The grotesque, often humorous interludes, where Lynch indulges his surreal fantasies, serve as a safety valve, releasing some of the tension from the overly inflated balloon of emotion. This production is undeniably a product of its time, perfectly capturing the mood of American society as it entered the 1990s. Just two years after the film’s release, the metaphorical balloon popped. Like Lula, who couldn’t bear to hear any more bad news on the radio, the people of Los Angeles left their homes and took to the streets, releasing years of pent-up emotions. This moment in history became known as the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

Thus, Wild at Heart is a strange, ambiguous film. On one hand, it’s much simpler and more straightforward than the films Lynch usually makes. On the other hand, hidden between the scenes and stops along the way, are incredibly deep emotions. Watching Wild at Heart sometimes makes you want to scream, to release all your negative emotions like Sailor and Lula, throw on a snakeskin jacket, and start life anew. This, ultimately, speaks to the film’s exceptional nature.