BE RIGHT BACK Explained. Black Mirror’s Best Episode?

However, I recently revisited Be Right Back episode (Season 2, Episode 1).

Naturally, the following text is intended only for those who have seen Be Right Back. I encourage everyone else to watch Black Mirror, which, as a colleague from the editorial team once noted, is one of the best things offered by those responsible for showing images on TV screens. It’s definitely worth indulging in a bit of “healthy masochism.”

Why Be Right Back specifically? Because it touches on a theme as old as culture itself, which in its various configurations will essentially be the main subject of this text. Trauma, grief, the desperate desire to regain a loved one who was with us for years but left suddenly, just like that, forever. This is the foundation of the episode. Ash, Martha’s husband, dies in a car accident. She was supposed to go with him, but work kept her permanently tied to a modern graphic station located in a rather old-fashioned looking room. This only intensifies her sense of guilt and hopelessness because she could have been with him, and they would have left together, showing a middle finger to the neat phrase “till death do us part.” But things turned out differently.

The world of Black Mirror, however, is a world of apparent possibilities. Technology replaces mythical gods and deities, angels, demons, and magical incantations. Orpheus descended into Hades thanks to the miraculous sound of his lyre, which charmed Charon, Cerberus, Persephone, and Hades. To bring a statue resembling a human to life, Pygmalion had to win the favor of Aphrodite. To create a Golem from clay, a rabbi had to bring it to life with the word “emet,” which means truth and differs from death (met) by just one letter. In Be Right Back, all Martha needs is a computer and a credit card.

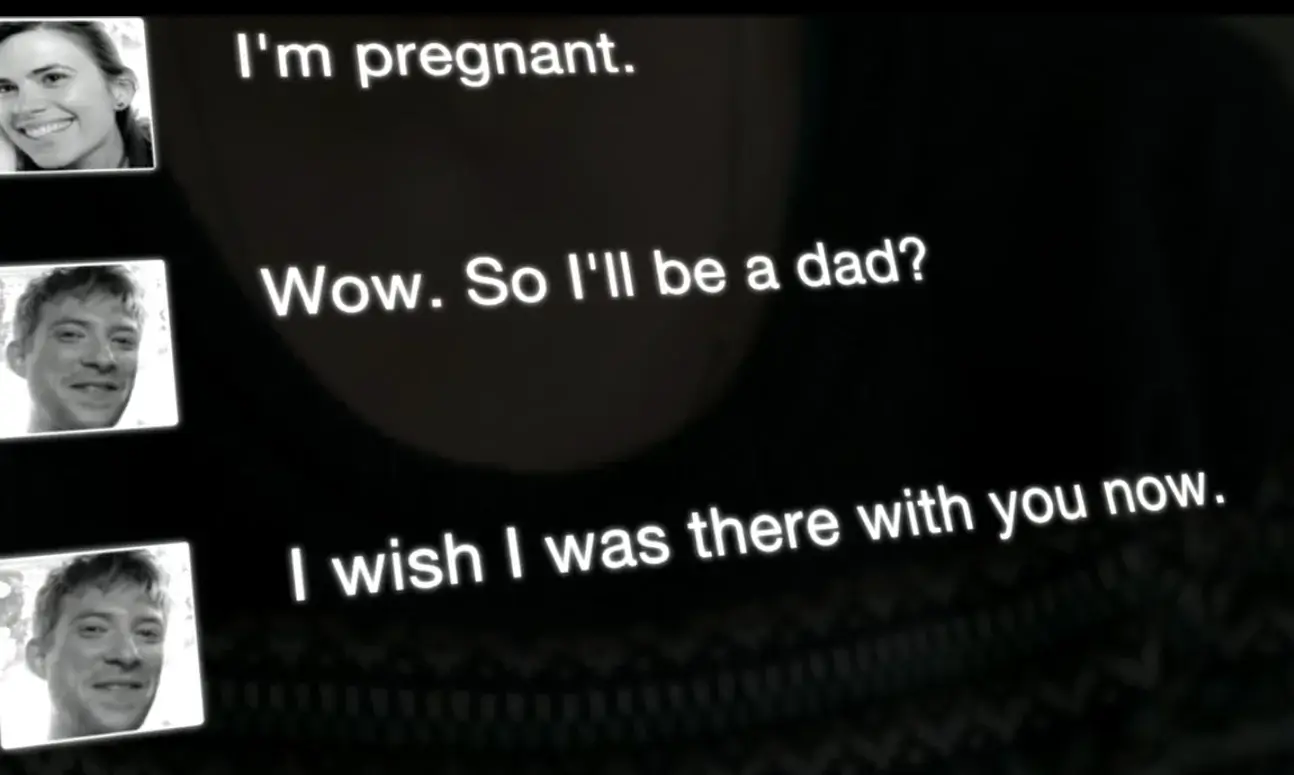

At first, Ash returns as text on a computer screen and a voice on the phone. Thanks to synchronizing data from Facebook, Twitter, email accounts, online forums, as well as private videos, conversations, and photos uploaded to the computer by Martha, the program can create an algorithm that thinks like Ash. Thanks to the magical power of a credit card and purchasing an additional subscription, a life-sized phantom arrives at Martha’s house (the program, of course using Ash’s gentle voice, persuades her to buy it). Initially, the woman is disappointed because the mannequin does not resemble her late husband at all. The voice from the phone says this is normal because the body is empty at the moment. Martha needs to activate it, putting a piece of parchment with the word “Emet” in its mouth. When the process of “filling” the empty body is complete, ash stands before her – and here I emphasize that I intentionally write his name in lowercase letters. After all, he’s more of an object or ash than a person.

The new Ash is born in a bathtub, where – thanks to a mixture of water, a mysterious electrolyte, and the program’s activity – the phantom’s body is “filled.” Martha acts like a medieval alchemist trying to create a homunculus. Paracelsus, now considered one of the fathers of modern medicine, even developed a potion intended to create an artificial human. It was supposed to consist of urine, semen, and blood, acting as “transmitters of spiritual material.” In Martha’s case, this transmitter is the electrolyte “that looks like fish food.” But who knows what is really in that unassuming packet?

Desperate for Ash’s presence, Martha doesn’t try to figure out what really happened. We could attribute this to the series’ convention, which transports us to an unspecified future. In Martha’s world, such phenomena might be normal, and the viewer gets to know it only within the narrow confines of the area surrounding the protagonist’s home. On the other hand, the further development of events rather negates this possibility. The woman’s growing surprise and disappointment indicate that she didn’t fully understand what she was getting into. It’s also significant that before beginning the second (bodily) phase of Ash’s return, Martha was informed that this stage of the project’s development was still experimental. Thus, the protagonist wasn’t acting rationally. She indeed behaved like an alchemist trying to find a loose brick in the wall separating life from death. However, culture teaches us that such pursuits are usually exceedingly dangerous.

At first, Martha is thrilled with Ash’s return. She succeeded, repeating the act of creation and achieving the result she desired. The most terrifying thing about Black Mirror, however, is that such things happen without cemetery visits or Frankenstein’s lightning bolts. A bathtub, money, and a few bars of signal are enough. You don’t even need to read the instructions because the voice on the phone will tell you what to do. Returning to Martha, her first night with Ash is amazing. His slight incompetence in some aspects is something new and charming for her. For example, the new Ash doesn’t know how to behave in bed because the deceased man didn’t share such information online, and Martha didn’t upload any materials related to that part of their relationship to the program’s database. But all of this pales in comparison to the fact that the lost man has returned. What’s more, Martha, with undisguised enthusiasm, exploits the algorithm’s minor weaknesses and enjoys when she can improve her creation: at one point, she notices that the new Ash is missing a mole, and the program creates it within seconds. The man is in her hands, a malleable material that (with some limitations due to his programmed nature) she can modify according to her needs. The new Ash is thus a submissive being. And this is where the trouble begins.

Martha’s initial enthusiasm is reminiscent of the case of Nathanael from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Sandman. The 1817 short story perfectly highlights the aspect of personality awakening in the woman happy with her husband’s return. Hoffmann’s main character falls in love with a mysterious beauty named Olympia. His obsession with her gradually alienates him from his sincere friend and former partner, who starts to seem overly critical and thus less attractive. Nathanael ultimately decides to break off old relationships and start a new life with Olympia. This decision is cemented at a ball where the woman reacts to his every word with a soft, approving sigh. Shortly after proposing, however, the protagonist witnesses a situation revealing that Olympia is a human-like automaton. During a quarrel between the constructors, the machine loses its sight. It is the sight of the bloodied eyeballs lying on the floor that drives Nathanael mad.

Martha shares with Hoffmann’s protagonist the infatuation with the machine’s submissiveness, confusing its greatest weakness compared to a human with a trait that would make it better than a real partner. Nathanael is deceived and chooses Olympia, who agrees with his every word, instead of Clara, who begins to seem problematic, disagreeable, and therefore seemingly mismatched with him. Martha, on the other hand, is satisfied with the new Ash. The first evening in his company is happy, even ecstatic. However, this state of affairs indicates that his appearance interrupted a mourning process that definitely hasn’t been completed yet. When the woman, despite being fully aware of the artificiality of her partner, decides to lose herself in his arms, she forgets why she brought him to “life.” Just as Nathanael forgot about Clara, Martha forgets about Ash. Sobering up comes in the morning, but by then it’s too late.

What happens to Orpheus trying to retrieve his Eurydice, Frankenstein creating the Monster, various golems, homunculi, or automata simulating life? Most often, death lurks behind them, fully aware that someone dared to challenge it. Orpheus goes mad from his loss and is torn apart by the Maenads, Frankenstein’s Monster kills the creator’s family, while also contributing to Victor’s death. Golem stories often involve mass murders and immense destruction, and even alchemists used to call imaginary homunculi “man’s demonic servants,” while automata are sad representations of the deformity of the act of human creation.

The morning after a passionate night with the new Ash awakens Martha from the “Nathanael’s stupor.” The woman starts to realize that her tortured mind and senses have deceived her. Each passing day only confirms this, but it’s not easy to get rid of something that so perfectly imitates a living being. The new Ash is, in fact, an accident, a specter that arises because, at some point during Martha’s intimate requiem, the orchestra rebels. A failed ritual results in the appearance of a demon. Building on the thought in Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia, Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok describe the process of “incorporation,” which is a neurotic obstacle to introjection (a properly conducted mourning process), a response steeped in melancholy. The subject doesn’t accept the loss because the lost object served as a mediator in their relationship with their inner world. So, they try to fantasmagorically, magically, possess the desired object, which – enclosed in a crypt – becomes a “living dead,” and as Jacques Derrida says, the inhabitant of the crypt is the deceased whom one wants to keep alive, but as deceased; whom one wants to preserve even as dead, but on the condition of preservation, and thus whole, intact, healthy, and thus alive. (After: Wojciech Michera, Beauty as the Beast, Warsaw 2010).

The desire to physically bring Ash back reveals this very paradox. Marta tries to come to terms with his death, to keep him in her memory as deceased, understanding that the memories in which he participates ensure that he remains a symbolic part of her, thus preventing him from being entirely gone. Unfortunately, the rationalization of grief fails. The protagonist breaks down when a well-meaning friend registers her in a program simulating the deceased man. A single email from the “crypt” is enough to draw her into a dangerous game. From that moment on, Marta desires to preserve the memory of the deceased as much as to keep him alive. This is evident through her increasing dependency on the program simulating the lost man. The lid of the crypt is lifted, and into her life enters a “living corpse,” the New Ash, whom, paraphrasing Fritz Lang’s classic Metropolis, should rather be called the False Ash.

His presence prevents the completion of the grieving process and the return to normal life. In the context of the Orpheus myth, Maurice Blanchot wrote that Eurydice, who would have returned from the underworld, would be only her own image, linked to the world where she appeared only as an image—a dark possibility, a shadow always present behind the living form, an image that now, far from separating from it, transforms it into a shadow. (From Maurice Blanchot, The Instant of My Death, translated by Elizabeth Rottenberg). The False Ash is the fulfillment of this eerie prophecy, meaning that every, even the briefest, glance in his direction reminds Marta that her beloved is dead (I mentioned this paradox once in the context of Tarkovsky’s Melancholia and Solaris). The reminder of death is not the same as bringing someone back to life; quite the opposite. The False Ash is merely an image composed of Facebook and Twitter posts, vacation photos, or email conversations. He is a shell detached from essence. He lacks what alchemists would call the spiritual material, what we commonly refer to as a soul. It is life without life, which is death.

Be Right Back, like the entirety of Black Mirror, is perhaps the first television creation that so strongly warns us against placing too much trust in images, which are, after all, the foundation of this medium. The most powerful aspect of this series, however, is that it doesn’t venture too far into fantasy. Despite setting the action in the future, it fits perfectly into discourses present in the humanities for many years, remaining very close to contemporary issues. In the finale of Marta’s story, I was only waiting for some form of her symbolic blindness (something akin to the torn-out eyes from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story). I expected dark glasses, but that empty, prominently displayed gaze is perhaps even better. It is proof that one can look and not see, just like Nathanael.