The sandworms are dragons, and DUNE is not SCIENCE FICTION, but rather FANTASY

Regarding the fact that Dune is not science fiction but rather retrofuturistic fantasy, I am much more convinced than in the case of Star Wars, which at least create pseudoscientific appearances explaining the technological achievements used by individual civilizations, including humans. Isaac Asimov in the 1950s defined the genre boundaries of science fiction as a literary expression that explains the “impact of scientific achievements on human life.” Dune does not do that. Dune explains the influence of court intrigues and the mystical spice on human life. Herbert does not engage in scientific discourse, does not adhere to the principles of probability and empiricism, even in futuristic visions, but rather bases his narrative on the description of political and social transformations, which are a copy of our medieval world. For better reception, it has been enriched with a pan-anthropomorphic cosmos, interstellar travel, some mutations, religious metaphysics seasoned with the psychotic effect of melange, and a bit of technology, albeit stylized as retrofuturism. However, the principles remain the same as in the 15th and 16th centuries. There is no science fiction here, although perhaps there was still some in the 1980s, during David Lynch’s time, at least aesthetically. It disappeared in Denis Villeneuve‘s era because it became ascetic.

However, what links Star Wars with Dune and the genre of space opera are the so-called Force, equivalent to spice, although spice does not operate on such a scale, does not permeate the world with its force, and connections with invisible to the naked eye matter. The spice only activates these “psychomagical” connections in the universe, the basis of which in Star Wars is the Force. Lucas therefore went deeper, and perhaps even more scientifically explained through specific events, the midichlorian construction of the universe, which again brought him closer to science fiction, something Herbert did not do in Dune because he had a different narrative goal, and also constructed the genesis of the world differently, which had enormous consequences for the genre affiliation of the entire universe.

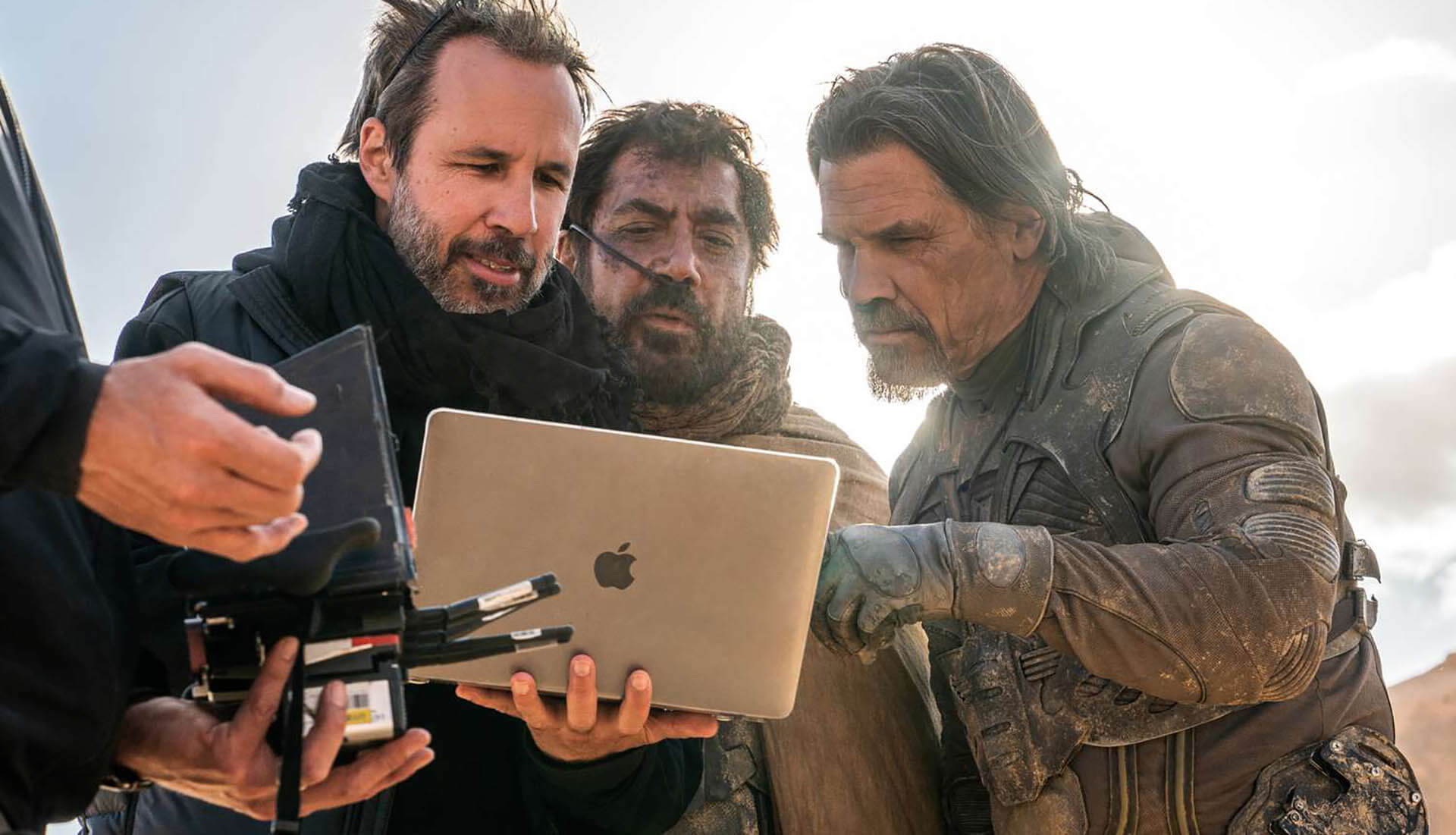

Of course, it is no reproach that Dune is more fantasy with retrofuturistic elements than science fiction – objectively none. Subjectively, however, for many hardcore sci-fi fans, it will likely be a devaluation because within their worlds, science fiction stands higher than tales of magic, swords, princesses, and court intrigues, albeit set in space, creating something akin to space opera. Similarly, science fiction in the perspectives of fans exceptionally grounded in earthly and contemporary psychological dramas will be a genre too full of unreal inventions to be mature. Genre classifications influence valuation, which they shouldn’t. However, it’s difficult to apply measurement using analytical arguments to emotional reactions. In the case of Dune, it’s probably the same, except I’m writing about it because for me, it’s not emotions when I assign Frank Herbert’s universe more to fantasy than to science fiction. This is a statement of fact, a complement to classification, a purely logical process, not an emotional one. The film adaptation of Dune as both fantasy and science fiction will remain equally valuable worlds belonging to the broadly understood fantasy genre for me, which finally saw the light of the film through the talent of Denis Villeneuve, despite numerous differences from the literary original. I’m referring to changes in chronology and consequently the roles of Alia and Paul in the killing of Vladimir Harkonnen, as well as the resolution of the final scene in the film and the book. In the film, Chani escapes with the help of a sandworm to the desert, showing that her position is much stronger than Jessica, Irulan, and the Bene Gesserit order presume. In the book, she is much more passive. She is to fulfill the will of her “Messiah” – to be in the shadow of Paul, who sets out to conquer the universe, incidentally a very authoritarian and monocultural conquest, and wait until the kind history calls her “wife.” These, as well as other changes, do not affect my assessment of the adaptation because Villeneuve had the right to emphasize certain threads and weaken others. Genre affiliation does not matter in assessing quality but does matter in the context of changes made by the Canadian director.

The ending of Dune, both in the book and the film, is purely fantasy, but Villeneuve emphasized this belonging to the world of magic and swords even more precisely by the presence of the sandworm. This brings to mind a common technique used by characters in RPG games when they summon their mounts – not only horses but also other typically magical creatures – which allow them to escape from deadly situations. This is exactly how Chani evacuated, returning to the place she believed she belonged to, while Paul wanted to uproot her from there almost by force. Not particularly, but Villeneuve brought his story closer to fantasy in the finale. However, not only the conclusion of the story in his interpretation matters, but also the development and the middle, although the director had less influence on their genre affiliation.

Let’s start with the key confrontation between Paul Atreides and Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen. It’s a classic duel of medieval knights for honor, domination, and women. And most importantly, it takes place using melee weapons. Generally, melee weapons dominate in battles. Battles are fought hand-to-hand, as knights in armor once did. Moreover, specific shields mostly protect against quick sword strikes but do not protect against prolonged pressure from a blade. It’s like cutting hard, mature cheese like Parmesan with a knife, if someone ever comes up with such an idea, instead of grating it with a grater. Shields in Dune succumb to blades, but it takes time and strength to drive them in, similar to steel armor, which protected against cuts but coped much worse with heavy sword strikes, axe blows, crossbow bolts, and stabs, especially supplemented by the momentum of the whole body. In Dune, the role of machines has been minimized. This was justified by the consequences of the Butlerian Jihad when humans won the war against machines but never returned to using artificial intelligence. The action of the spice enabled travel over vast distances in the Galaxy, but it is still difficult to believe that without microprocessor technology, it was possible to build spaceships and move in space. This technological regression of the universe to an almost analog era largely determines the genre affiliation of Dune. Translating all achievements with the spice is exceptionally illogical. Lasers, atomic weapons, navigation, even over small, interplanetary distances cannot occur without automation. As for the entire process, the world cannot persist for thousands of years without development, which is the natural dynamics of any thinking civilization, and that is exactly how it is after the Jihad in Dune. The world persists, guided by the indescribable magic of the spice, enchanting all people, but strangely hampering their technological dynamism. Such persistence of the world in one stage of civilizational development is CHARACTERISTIC OF A FANTASY WORLD, where millennia pass, and battles are still fought with swords and spells, so-called voice.

Other elements that determine the fantastical-magical character of Dune are the totemic relationship with animals, specifically the sandworms on Arrakis, which is connected with the expanded metaphysical sphere of the relationship with religion, tradition, ritualism, and generally social phenomena in the universe. It could not be otherwise if humanity had access to advanced technology. Feudalism, patrimonial monarchy, and class-based society stylized in the customs of ancient great dynasties such as the Tudors, Angevins, Plantagenets, and even the Ottomans could not exist. In the world of science fiction, there is no place for such a developed non-empirical, folk, and traditional element. I’m thinking here of the activities of the Bene Gesserit order and the evolution of the spice that Paul Atreides undergoes, transforming into the future-seeing leader of the Fremen, which is actually synonymous with being their Messiah, and then Adolf Hitler of the entire Galaxy, who during the 12 years of war contributed to the deaths of over 60 billion people and the devastation of hundreds of planets, after which he himself became the Emperor, maintaining the status quo built on the principles of the Corrino dynasty, namely Shaddam IV. Science fiction eliminates from its content all such miraculous elements, replacing them with empirical verification and scientific description, at least attempting to base it on the theory of probability. Considering Dune from this perspective, attempts to classify it as science fiction can be compared to desperate attempts, caused by emotional fear, and therefore a desire to throw vegetable peelings at mosquitoes. That’s why the walls of our houses in the spring will be covered with the remains of the long legs of these useful and completely harmless insects to us. Yes, they’re flies too, but just not blood-sucking mosquitoes. So, before you repeat the narrative of science fiction fans frightened by the thought that Dune could be found in a group of infantile tales about princesses, dragons (the sandworms are kind of dragons, except they don’t speak human), and the search for life-giving artifacts, think whether it might already be there due to its most Dune-like, characteristic features; and whether it really takes away any value from it.