THE LAWNMOWER MAN. The very first cyberpunk sci-fi

… (while also representing the teeth of a demonic character). It’s somewhat like an endlessly looping screensaver that turns the victim into a complete vegetable. I couldn’t help but get the impression that the The Lawnmower Man is doing something similar to its audience. One might think that it should be turned off while it’s still possible. Well, not necessarily, because then you’ll miss out on a truly wild ride on the back of a crazed lawnmower from the ’90s. Many of us are familiar with this title. Many have seen it. Somewhere. Sometime. Often in childhood. I believe that all those who have forgotten about it or simply prefer contact with the titans of the sci-fi world (such as Alien, Robocop) should give it a second chance. Watch a film that suggested computers would change our lives, turning us into IT tough guys—binary heroes packed with megabytes of muscles, large brains, and unlimited development possibilities. Now that we are all connected to the network, let’s explore how Hollywood visions of our interactions with electronic reality evolved. It will be a journey into the past—bumpy but extraordinary. Here is a film from a time when the whistling and crackling sounds of a modem gave people shivers and brought to mind an expedition into unknown, exciting territories.

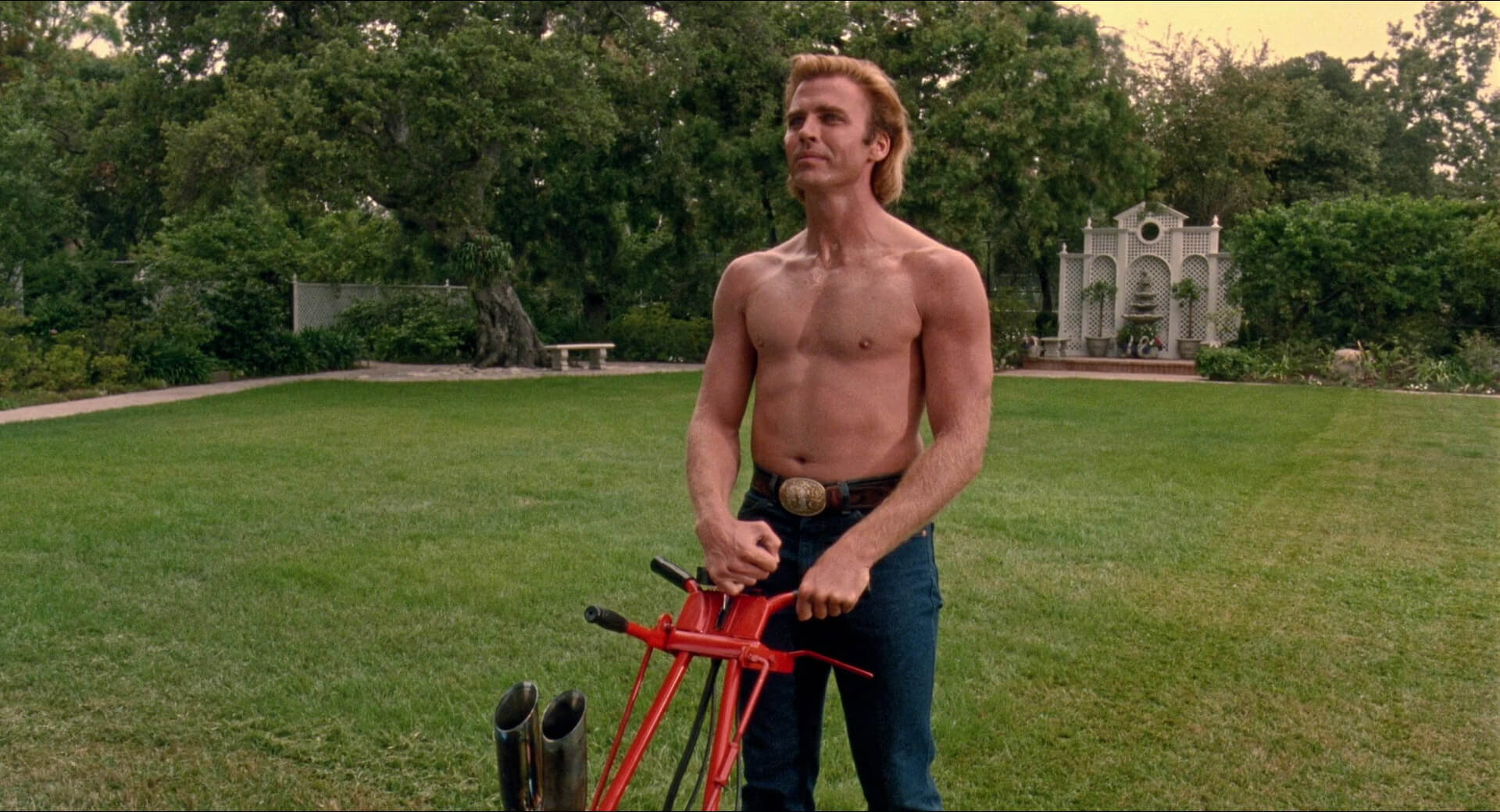

In The Lawnmower Man Dr. Angelo conducts research for a government agency on the impact of information technology on living organisms. After a failed experiment with monkeys (they became dangerous, so they had to be destroyed), he finds a new subject. It’s Jobe – a developmentally delayed young man mowing lawns in the area. A gentle and good-natured guy with a halo of straw-blond hair, who always looks as if birds are chirping above his head, doesn’t have an easy life. He is bullied by a twisted priest (in a scorching exaggeration; the character of the clergyman may be reminiscent of a similar figure from Braindead) and a dim-witted beefy guy from the gas station. Angelo decides to upgrade Jobe by offering him an accelerated course in cyberspace, vitamin and hormone injections. The young man gradually begins to change. He becomes more robust, dons cowboy boots, confidently enters a neighbor’s house offering lemonade (she previously declared that her overgrown lawn needs a quick trim). Soon, he also learns to say “no” with a resolute voice and is ready to settle scores with the world. The question is whether Angelo will retain any control over the direction of his ward’s transformation.

The Lawnmower Man is a cheesy film, full of eye-catching scenes and surprisingly bubbly. However, if you abandon the expectations set for good cinema, you can at least have some fun. Let’s start with the fact that the movie is not an adaptation of Stephen King’s novel. New Line Cinema used the rights it had to the author’s story, borrowing only the character’s name and then advertised its film as an adaptation of the master of horror’s prose. It was a successful marketing ploy, but also a plain deception. King demanded the removal of his name from promotional materials. I don’t blame him. Firstly, we have an unsuccessful film here. Secondly, how do the cyber attractions, full of computer animations, relate to the spirit of King’s analog, old-school creativity, as seen in The Shining? I can already imagine King’s expression trying to somehow digest these cyber-bits of the film…

Everything here is either perplexing or amusing. Take the main character, for example. Jeff Fahey played him, specializing in secondary thrillers and action movies, often made for television or directly for the DVD market. This actor—rather stiff, with limited skills—played a mentally challenged person with exaggerated ostentation, a thick line, and a lack of moderation in the dosage of role components (lots of silly expressions, showcasing unnaturally large teeth, etc.). Pierce Brosnan—still before his role as Bond and his biggest successes—has more charisma and class, but in this film, he can only put on a good face for a bad game and display his chest under an unbuttoned shirt. Austin O’Brien also makes a brief appearance, known for My Girl 2 and Last Action Hero, but doesn’t have much to show. Certainly, the cast doesn’t deliver an acting masterpiece here, but it gives the film a very ’90s style.

However, there’s no hiding the fact that the real star and attraction here was VR (virtual reality). It appears on the screen for a whopping eight minutes, consuming a considerable part of The Lawnmower Man ‘s budget. How did the first extended and elaborate scenes of exploring digital reality fare? With the help of gloves, goggles, and a metal harness supporting the body of a cyber-diver, the characters jump into another, colorful world, where fountains of data, streams of information, and new, unknown paths of development await them. From today’s perspective, however, we have a visual nightmare. The cyberspace in The Lawnmower Man is flat, garish, tasteless, devoid of atmosphere, and devoid of the ambition to be anything more than game snippets. It’s some strange bubbles, colors straight from Paint, and angularity you never dreamed of. The exploration is further discouraged by the pathetic dialogues during the characters’ “surfing” and the stiff pseudo-mystical music. The pinnacle of imagination is floating among pixelated, multicolored jelly or the sex of two blobs over an exceptionally ugly sea—everything trying to pretend to be a transcendental immersion in unimaginable beauty.

To give credit to the film’s creators, the VR of that time often looked just as cheap, but it cannot be denied that transferred to the cinema, it boycotted all attempts to build an atmosphere or seriousness. No problem. As it turns out, the “ordinary” scenes also attacked the viewer directly under the banner of cheapness. Here’s the whole transformation of the protagonist looking like the squeezed-out “want” of some teenage screenwriter from the deepest recesses. Jobe sits in the network for a while, absorbs new data, and then, with his hair tousled, becomes something like a likable cowboy—sharper and less awkward, with a slick hairstyle. Then, he evolves further to finally become the Darth Vader of the cyberworld: reading people’s minds (even Brosnan, who tries to reject this brain intervention with spread fingers, a sad face, and a pained voice), and imposing his will on them. He mows lawns, controlling the lawnmower with his gaze, and uses mind power to squeeze toothpaste. At some point, he transforms into the punishing hand of digital justice. Standing in the dark of night, with disheveled hair, illuminated by beams of light in a tight cyber-astronaut suit, with his gasoline lawnmower, which will now become his sword—Jobe looks grotesque. His revenge on bad people will make you burst into laughter more than once. There are plenty of religious motifs in The Lawnmower Man: the virtually crucified Brosnan, the burning of the priest in the fire of pixels, the use of a low-resolution locust. Not entirely religious, but very impressive is the breaking of people into… flying dragees. Eventually, Jobe also becomes a god. Or thinks he is.

The government organization is also grotesque, ready to do anything to maintain control over the “upgrading” project of Jobe and eager to obtain a new type of human weapon. The big, menacing face of the head of this organization during a teleconference, shattering a cathode-ray tube screen; dark, cool, super-secret laboratories; guys in black with guns. How much finesse and originality in this! Everything in Brett Leonard’s film smells like a cheap comic book.

Surprisingly, just a year earlier, Terminator 2: Judgment Day premiered—the holy grail of action cinema, which still amazes with its precision, scope, and fantastic special effects. By the way, it also confronts the viewer with the theme of technological threats. On the other hand, The Lawnmower Man was, in a way, a precursor to films about people plugging into devices of modern technology. Strange Days, The Thirteenth Floor, or Johnny Mnemonic—also not entirely successful but more digestible—were yet to come. So maybe filmmakers just had to wander before they could reach the level of The Matrix or eXistenZ? The Lawnmower Man wanders like a drunkard in a room full of mirrors. And yet today, a quarter of a century after its premiere, it reveals its unusually comedic potential. It’s so bad that it’s good. It also earned $150 million and spawned a sequel so bad that it’s unwatchable.

The Lawnmower Man is the Maverick among VR movies. It’s worth a laugh. It’s also worth checking out how perceptions of the development of this technology were once shaped and comparing them with the current state of affairs. It turns out that the network—according to Dr. Angelo’s prophecy—has indeed encompassed everyone. Just gloves or goggles turned out to be unnecessary. We don’t need fancy devices or unreal animations to surf. VR still comes in handy—for simple entertainment but also to train soldiers or help autistic individuals cope with their condition. However, it did not turn society into people locked in basements, onanists, or game-addicted maniacs. I’ll say it again: it turned out that we can be them without unnecessary entourage. So turn off Facebook and like this movie. Not by clicking on some icon but straight from the heart.