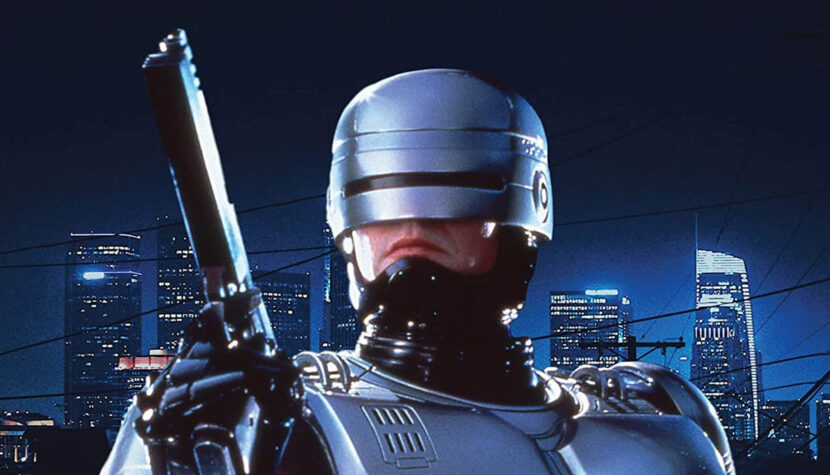

ROBOCOP. They don’t make movies like it any more

Have you ever wondered why the history of art only conveys what is good? Why does it only unearth extraordinary things worth repeated viewing from the past? Where are the hideously constructed cathedrals? Show me just one cathedral vault that’s grotesquely adorned. Where are the tacky Roman circuses? Horribly botched frescoes from ancient times? Where are the Egyptian botches, Babylonian eyesores? Why could some Renaissance Pope be a patron, but contemporary ministers of culture and art can’t? Why don’t we find repulsive ornamental trash, nauseating imitations, monumental kitsch in archaeological excavations? How the devil did it happen that even monuments erected to various leaders and rulers were so exquisite in the past, but today, if someone puts a bust on a pedestal, not even a drunkard will resist it, he’ll just urinate and cross himself for the road?

They don’t make films like RoboCop any more

Why is it today that what worked so well “back then” let’s say, 30+ years ago, in the days when Verhoeven and Bottin put together RoboCop, can’t seem to be replicated? Creative indolence? Or perhaps, at the twilight of the era of carefree Reagan-era militarism, the California streets suddenly swarmed with enlightened, sensitive, and intelligent people, and now only masses of uneducated, impoverished plebeians spill into the movie theaters? I myself have sighed with nostalgia at the thought of the analog era many times and repeated like an incantation, “those were the days, and now it’s just a mess.” Is it nostalgic whining of the perpetually disappointed individual or something more collective?

Whatever it may be, one thing is certain beyond any doubt: they don’t make films like RoboCop today. Even after a million viewings, I am still fascinated by the classic clarity of the plot, perpetually amazed by the timeless sound of Poledouris’s music, and while watching Boddicker, with the help of his deviant gang of thugs, tear apart Murphy’s body, I still feel the same anger as when I was a kid, sitting in front of the TV for the first time to watch RoboCop on a worn-out VHS tape.

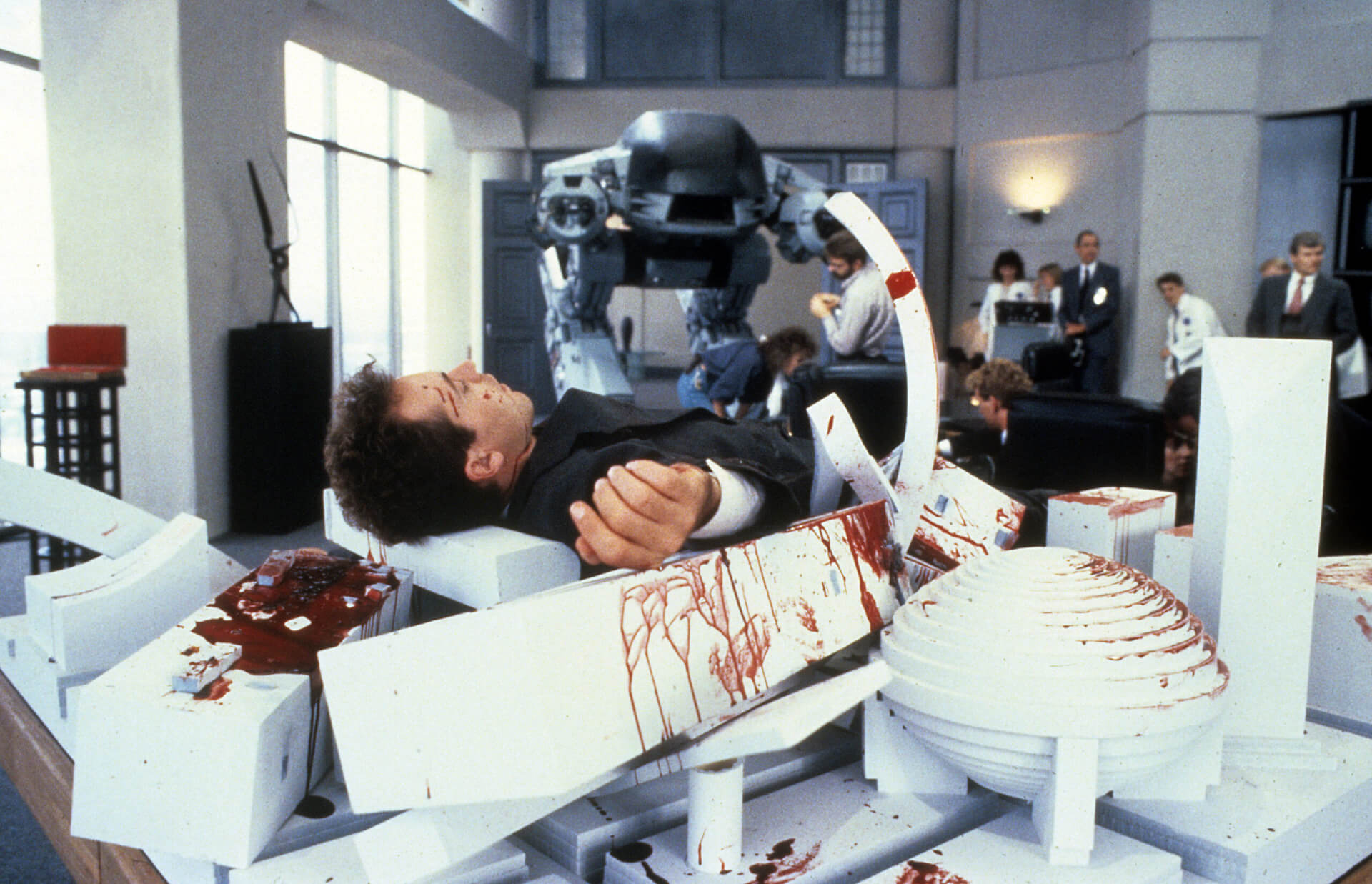

Murphy’s execution

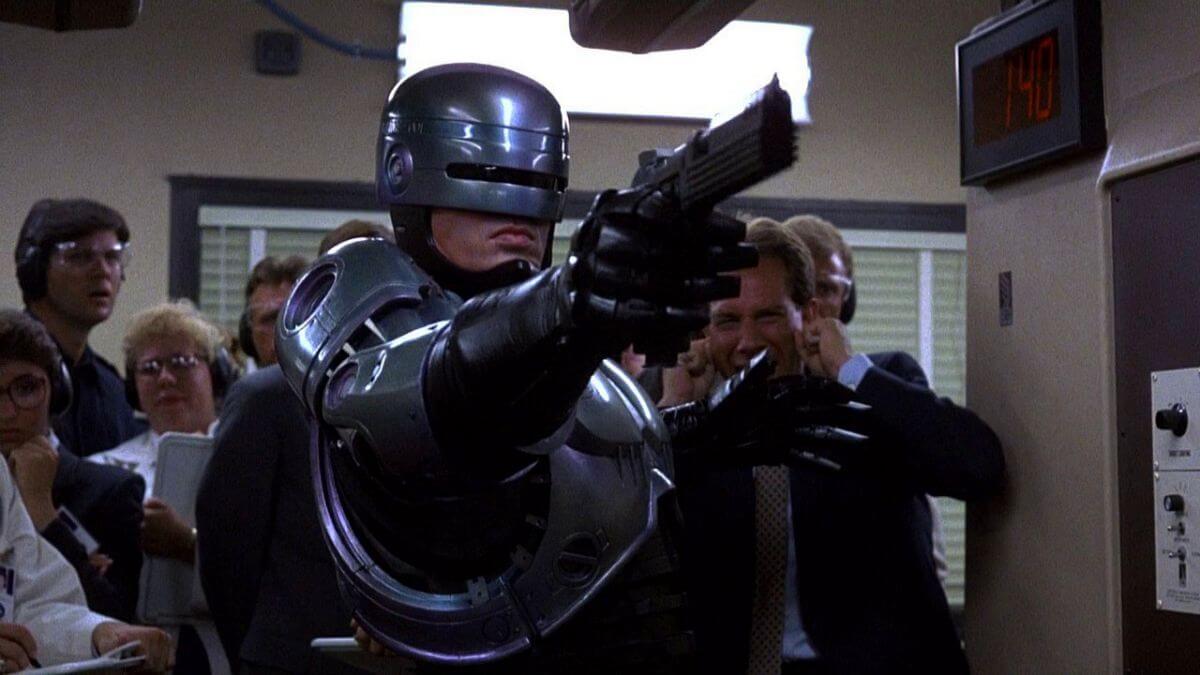

The execution of Murphy – shown frontally, without any retouching – has lost absolutely none of its barbaric cruelty over the years. In the flood of various Saws and other teenage “horror” films, the brutality of movie degenerates is often trivialized. But not in Verhoeven’s case. He plays with the audience’s emotions with masterful ruthlessness. Before his character dies with a bullet in the brain, he takes a massive enemy onslaught to his Kevlar-clad body. His partner watches the event from behind a grating. I genuinely feel sorry for that girl. A related motif, passive witnessing of a partner’s execution and the infuriating inability to make any gesture, will return later in Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, but with slightly less impetus – without Verhoeven’s typical sadistic literalism in violence portrayal. Both sequences taking place in the deserted steel mill – both the initial one and the final one with the guy dissolved in acid – have permanently entered the canon of the most brutal scenes ever.

Take anyone you randomly encounter and ask them if they’ve seen RoboCop. If they answer that they have, ask them what they remember. I bet dollars to donuts they’ll remember the execution scene. The older crowd often reminisces that RoboCop was one of those 18+ films you couldn’t get into with a school ID for anything in the world. You had to do some serious gymnastics to bypass the regime inspection at the ticket booth.

But let’s leave the memories behind and get back to the point: the movie also sticks in your memory thanks to the optimally demoralized gang of psychos. The figures of hooligans ooze such unimaginable vulgarity that while I was previously ready to justify their criminal actions with their thug profession and the will to survive in clashes with the police, from the moment Murphy was dismembered, I hated Boddicker without reserve. All criminal ideology evaporated, turned into nothingness. Hence the constant rush towards the finale, which accompanied me during each subsequent viewing. I wanted to see Robo crushing his tormentors, rolling over them like a tank. I wanted spectacular revenge, and that’s what I got. But wait… what are we even talking about? Revenge? The machine is seeking revenge? Something doesn’t add up here – since when does individual sense of justice override commands typed on a keyboard?

A man who becomes a machine

Sometimes I get the feeling that Verhoeven is clinically incapable of making a lousy film. In RoboCop, he occasionally puts in such zest that it’s mind-blowing. Because from this story emerges a cool and quite intelligent humanistic thought. Its glimpses can be seen even despite the lamentable condition of the world, over which the chrome-plated OCP behemoth reigns supreme. Englishman Scott (the older and wiser one), Canadian Cameron, and Japanese Oshii have brilliantly translated this idea into the language of epic cinema. It’s time to see what the Dutchman has to say about it. Here’s how I see it: the first part of the film tells the story of a man who becomes a machine, the second part tells the story of a machine that remains human. That’s what I say, and now I’ll try to prove this childishly simple thesis.

On one hand, Verhoeven piles up Murphy’s characteristics in the robot, all these sad details of his robotic existence. On the other hand, he places the living and inevitably human nature of the character in front of the audience. The result is that this character, as if cut straight from comic book literature, mentally outclasses all the currently promoted pumped-up icons of comic book heroes. The issue of blind obedience, accepting the degrading compulsion to consume baby food, and the struggle with memories swirling around in his head (the stroll through the deserted house is another proof of the director’s exceptional intuition) – these and other seemingly trivial matters play a role in the film no less important than the sensational plot of the police’s unequal struggle with the thugs running rampant in Detroit.

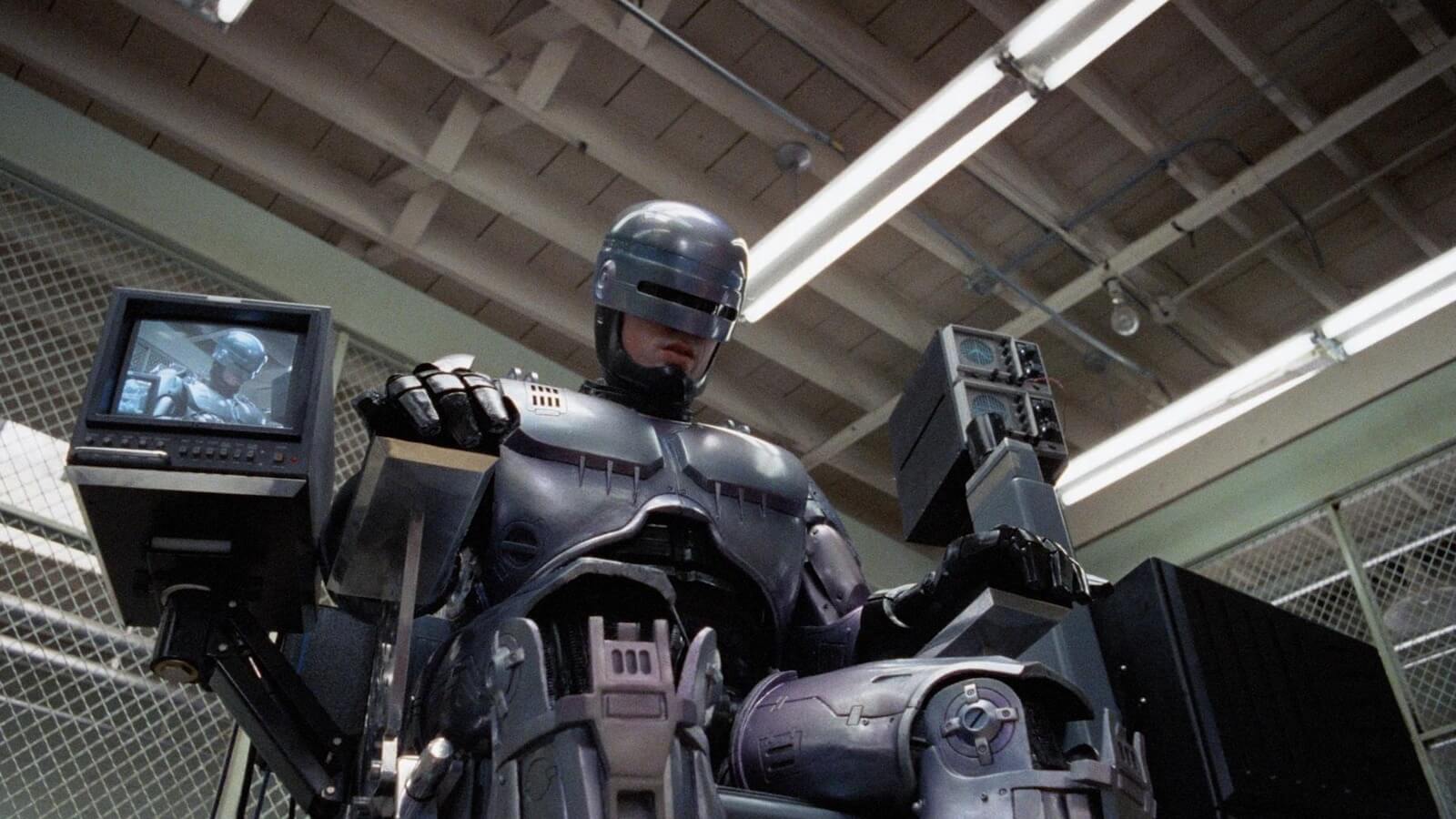

And so, at the dawn of his police career, Murphy will carry out his assigned tasks flawlessly: now he’ll participate in a few action-packed shows, then he’ll save a girl from rape, another time he’ll arrest a mentally unstable bureaucrat… In the end, he’ll be closer to a Zelmer kitchen appliance than a living being with a sovereign decision-making system. However, nothing lasts forever: the mission of a docile puppet in the service of OCP’s boys quickly turns the cyborg into something mundane. This, in turn, signifies a new developmental stage on the path to full self-awareness – a phase of rebellion and breaking the constraints of directives.

A machine that remains human

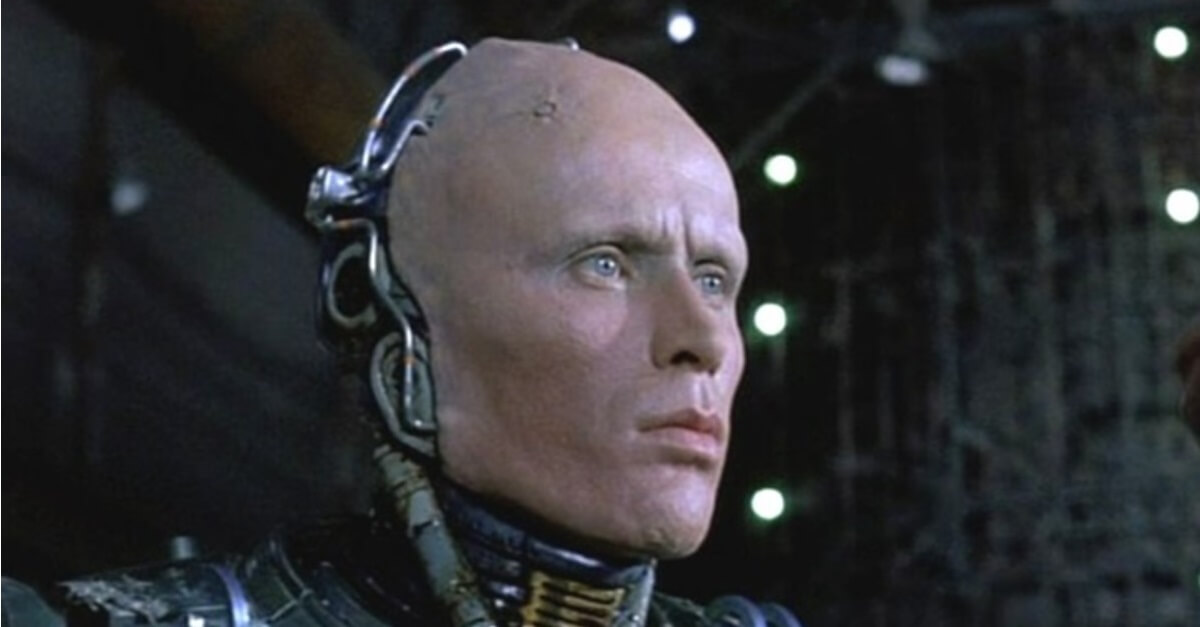

This stage of Robo’s adventures will become the domain of the second part of the film. The situation will clarify enough that only the brave Lieutenant Lewis will remain at Murphy’s side. This is perhaps the only downside of the film – a relatively small number of scenes with Nancy Allen. Her cheeky way of chewing gum is simply fantastic – I could fall in love with that. Anyway, after the incident in the underground parking lot involving the police brigade, both Murphy and Lewis will hide outside the city… in an old steel mill. The story will neatly come full circle. It is here that the best scene in the whole film will take place. In terms of the intimacy of the message, only the dying Batty’s monologue and Arnold’s conversation with young Connor about the human tendency to cry can compare with what will happen next. Robo will ask Lewis to find him a set of tools because the mechanism, battered in the clash with the execution squad, requires repair (a reference to the opening parts of the story). As he begins to unscrew the screws from his helmet, the cyborg will not forget to warn his partner (I love the emotionless voice of Weller delivering this line) that the sight she is about to see may not please her. The sight will be the entirely real human face of Murphy, the only organic element of the mechanical construction, the result of the stunning makeup work of Rob Bottin. But that’s not all. When Lewis holds up a piece of mirror to Murphy, he will again ask her for something – this time he will ask her to leave him alone with his own reflection.

Classic, ladies and gentlemen, pure classic.

In the mentioned scene of recognizing the human within, there will be an unusual absence of Verhoeven’s ubiquitous mockery. I wrote “unusual” because the vast majority of RoboCop’s scenes bend under the weight of the directorial satire, just as a leaf bends under the pressure of raindrops. The final part of the final battle with the head of the villains, when Murphy lies crushed under the debris and Lewis, seriously wounded, tries to crawl out of the swamp, is shattered by its ironic simplicity. Of course, I’m talking about Robo’s memorable one-liner, in response to Lewis’s complaints, he casually says, “They’ll fix you. They fix everything.”

RoboCop ‘s Irony

Verhoeven likes to play with irony. After all, he created a joyful mix of Hollywood clichés – a story about a group of soldiers battling it out with an interstellar bug infestation. But he does it differently than most filmmakers. He doesn’t treat irony as a rhetorical device. He only “seasons” the plot with satire, pushes it to the very bottom, and thereby doesn’t directly amuse the audience but acts secretly like a herbal remedy. Personally, I have trouble deciphering the humor in Starship Troopers. It’s a problem serious enough that I still don’t know if Verhoeven is “mocking” or simply asking questions through his work. The dose of irony in his films is so minimal (or, to put it differently, so precisely camouflaged within individual scenes) that it raises doubts about its presence in the film itself; it’s almost subliminal – it no longer comes from the director but is part of the depicted world, like the air. Do you remember when ED-209, that disabled combat robot with a limp in its right leg, tumbled down the stairs because it couldn’t step over a step? Or when one of the OCP board members, designated to assist in a simulated arrest, was literally torn to shreds by a hail of bullets because the procedure of revoking the order malfunctioned at that very moment?

Now show me a school that teaches how to shoot such scenes, or better yet, show me how to seamlessly integrate them into the overall story without causing its self-destruction. The sarcastic depiction of the not-so-distant future dominated by rapacious corporations is complemented by bizarre TV commercials and snippets of news, from which we learn, for example, about the tragic consequences of redirecting an orbital laser, which incinerated two US vice presidents. To make it funnier, these ad-news segments were hastily recorded and were originally not supposed to be included at all. Providence watched over the film’s production to the very end.

Allow me to summarize my thoughts succinctly: RoboCop is one hell of a film! Pay attention to the clarity and necessity of all the components of the plot, its beautiful intonation contrasting with the grim subject matter of the story. After all, RoboCop is largely the poignant story of a police officer who was murdered in the line of duty, a husband, and ultimately a father – a fact not to be underestimated! Verhoeven’s clear style enhances the dark richness of his imagination: contrast and harmony, style and substance, form and plot – everything is perfectly intertwined. Try to remove any fragment from the film, and the whole structure will fall apart. Verhoeven’s vision cannot be tampered with. With this peculiar statement, I conclude my review, hoping that when you reflect on your life through the lens of cinema (as I already do), you won’t forget the tin man with a gun in his thigh.

Films like this are no longer made today!