THE KILLER SHREWS. Guilty pleasure for the ages

The 1950s were marked by the looming specter of atomic annihilation hanging over the world, born from the Cold War arms race between the world’s superpowers. The Soviet Union and the United States engaged in various confrontations, the Red Scare consumed more nations, and fear deeply entrenched itself in the minds of people already weary from conflicts.

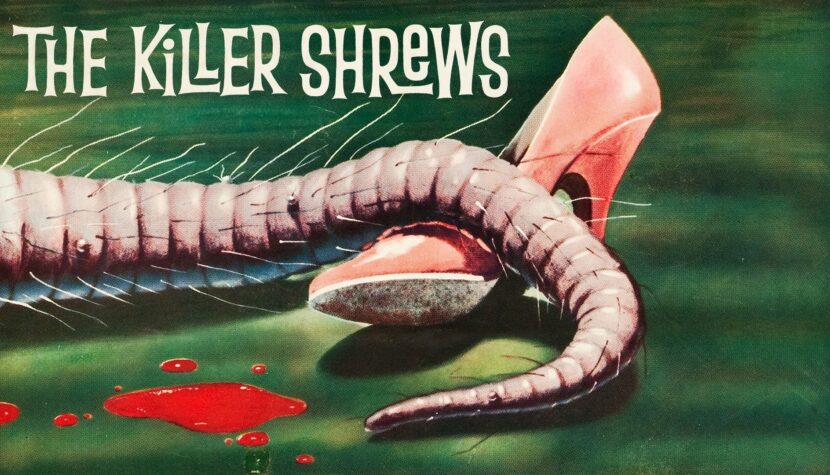

However, there were also a few positive aspects to this devastating clash. The rivalry between the competing nations led to remarkable achievements such as landing on the Moon, and the arms race facilitated revolutionary discoveries in various fields of science. Somewhere on the cultural fringes, but significantly to us film enthusiasts, this era brought forth various atomic monsters and space invaders onto the screens. The symbolism and message of these stories were meant to straightforwardly convey important issues (aliens often symbolizing communists pretending to be Americans, emphasizing the necessity of human cooperation against a common enemy, the dangers of playing with nuclear energy, etc.). Numerous films were made during this period (The Killer Shrews among them), most of them produced on a shoestring budget, aiming to capitalize on the popular trend and attract an audience with bizarre titles and extraordinary posters, which were often more impressive than the films themselves.

Of course, during that time, some true masterpieces of science fiction were created – The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) by Robert Wise, The Thing from Another World (1951) directed by Christian Nyby (although the legendary Howard Hawks oversaw the entire production; John Carpenter based The Thing on it), The War of the Worlds (1953) by Byron Haskin, Them! (1954) by Gordon Douglas (featuring a deadly ant attack, with elements of its skeleton and a few scenes borrowed by James Cameron for Aliens – the climactic battle), Godzilla (1954) by Ishiro Honda, and Forbidden Planet (1956) by Fred M. Wilcox. However, there were also some ideas that, especially at the extreme peak of the genre’s popularity, had been stretched to its limits, and films were made with extremely low budgets, particularly those featuring attacks by mutated creatures of all kinds. It was during this time that Ed Wood presented his magnum opus to the world, Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) – where everything but money from the producers and audiences was thrown in – and on screens, giant killer birds, leeches, praying mantises, crabs, and enormous eyeballs with octopus-like arms roamed (I recommend The Crawling Eye from 1958).

And that brings us to The Killer Shrews. It’s one of those films that owe their cult status primarily to the catchy title, promising something truly bizarre, but in a different way than today’s productions from studios like Asylum – from which we’ll remember only the extremely twisted titles in the future, like MegaShark vs. Giant Octopus or Three-Headed Shark Attack, but not the films themselves. Asylum lures viewers with promises of battles between the deadliest animals – sharks, octopuses, some dinosaur hybrids. Meanwhile, the people behind the 1959 film decided to scare us with shrews, which normally look like this:

Of course, for the purposes of the film, something had to be invented to turn one of the most charming creatures on the planet into The Killer Shrews. And it was done in a way that was decidedly too weird from a scientific standpoint (even taking into account that we’re dealing with killer rodents). The overall message of the film is a warning about the planet’s increasing overpopulation and the resulting specter of deadly famine. For this reason, scientist Marlowe Cragis came up with a not-so-brilliant idea to save the world. Since humans are the main component of the problem, it’s clear that reducing the amount of food consumed and the planet’s exploitation would be possible if the planet’s dominant inhabitants… were about half the size. So he decided to develop a scientific formula that would miniaturize the human species. He secluded himself on an island with his assistant Radford Baines, Ann’s daughter, her fiancé Jerry Farrell, and a Latino handyman, Mario – yes, it’s the full-blown 1950s.

However, these events occurred before the start of the The Killer Shrews narrative, as it begins with the arrival of Captain Thorne Sherman, responsible for supplies, to the island – a tough guy with a square jaw who was rather accidentally cast as the lead. On arrival, he learns that a serious hurricane is about to hit, and to the scientist’s displeasure, the hero will have to stay on the island for the night (with his African American helper – I don’t want to spoil it, but you can guess who will die first). The brave American quickly learns that the scientist’s experiments on animals (yes, those involving the miniaturization of humans) have led to the creation of dog-sized killer shrews that reproduce rapidly and are meant to simulate a sudden growth of the human race. However, they have already eaten almost everything on the island, so now they must wait until they devour each other. The characters have to barricade themselves in the building every night (of course, they don’t flee to safety for the sake of research) because the monsters come out to feed at night. But now is the moment when the KILLER SHREWS FIND THEIR WAY INSIDE THE BUILDING! <THUNDER>

Exactly! I mentioned earlier that the mutated creatures also have super-toxic saliva because they assimilated one of the doctor’s super-traps through their gums? (The guy consistently competes for the title of the worst scientist of the year).

On paper, it all sounds quite engaging and strongly resembles The Island of Doctor Moreau, but in execution, it looks much worse. The Killer Shrews suffers from the syndrome that afflicts the lion’s share of similar low-budget SF films from that era, where directorial finesse and ideas ended with the invention of the title and poster. The first half-hour of this barely one-hour production is hindered by a festival of talking heads and a pedantic explanation of this whole bizarre idea to combat world hunger, adorned with substantial anti-acting. Additionally, a stiff romantic subplot is woven into it, indispensable in such cinema, and unfortunately, the attacks of the killer shrews are marginal (the director, unfortunately, can’t create tension without them; and yet, almost two decades earlier, Jacques Tourneur had turned the art of suggestion into an art form in Cat People). You could easily skip the viewing and sweep the whole cult appeal under the rug if it weren’t for two things:

Firstly, it’s the way the bloodthirsty shrews are portrayed on screen. The film marked the directorial debut of Ray Kellogg, who worked on special effects for 20th Century Fox films after World War II and even became the head of the department responsible for them in the 1950s. He was concurrently working on The Killer Shrews and The Giant Gila Monster, both debuting in the same year (the latter being a clear Godzilla rip-off). So, he had some knowledge of creating unusual things on screen. However, his foray into directing didn’t go so well, as he only managed to direct one more independent film after this and assist John Wayne with The Green Berets. Yet, his vision of The Killer Shrews is a perfect example of do-it-yourself filmmaking with whatever is at hand. There wasn’t enough money for anything else, so in scenes where the oversized shrews were supposed to run and attack, they simply placed cardboard costumes with fur on German Shepherds. While this extended their snouts somewhat, the final results look more like severely emaciated dogs with rabies rather than shrews. The animals run freely, and the costumes fall apart as they move, requiring clever editing or the use of fence pieces to hide the flaws. For close-ups, puppetry was used, and these look fairly decent for their time, although the shrews only appear in the title. However, it must be admitted that the overall effect is charming (which isn’t necessarily good for a horror film) and if there were professional making-of documentaries for this kind of low-budget cinema back then, we would have one of the most interesting film documentaries.

Secondly, it’s the final idea to avoid a confrontation with the monsters and its execution. Without giving away any spoilers, the final fifteen minutes of the film introduce some inventive concepts and dynamic storytelling, which is a departure from the aimless gloom and peculiar concepts that dominate the rest of the film.

No wonder The Killer Shrews appears at various B-movie film festivals. It’s certainly not as good as Them! or It! The Terror from Beyond Space (without which there would be no Alien), as Kellogg’s work is rather haphazard and sluggish storytelling, a trait shared by many atomic-age SF films. However, it stands out due to its bizarre choice of monsters and their on-screen appearance. Plus, it’s in the public domain, so it goes well with a few beers and a group of friends without any pain.

Interestingly, in 2012, a sequel to the film was made, titled Return of the Killer Shrews, capitalizing on the catchy title from years ago. It looks like a trainwreck, and it’s not worth bothering with. Even the killer shrews in it actually look like shrews.