THE ABYSS: Still a Stunning Piece of Science Fiction

One could even say that the deeper we dive into the endless expanse of water, the more we desire to uncover all its secrets, the more we will be left breathless. And here a certain analogy is born. The similarity between space and the depths of the sea is quite perceptible in science fiction cinema. Both spaces overwhelm the human with their vastness. In both, breathing requires the right kind of suit. And finally – both realms are still so mysterious to humanity that they beg for the development of fantastic visions about how undiscovered organisms look and behave. James Cameron once embraced this idea in The Abyss.

After the cosmic adventure he provided for himself and viewers in Aliens, he decided in his next film not so much to come down to Earth, but to reach its deepest depths. The idea for an underwater film came to him while he was still in high school, during a lecture on deep-sea diving. It was there that he first heard about breathing using a liquid, more specifically, perfluorinated liquids, developed analogously to the amniotic fluid in which a fetus breathes. This led to a short story about a group of scientists working in a laboratory set on the ocean floor. Cameron, however, feared that scientists did not have enough commercial potential, so he replaced them with manual workers – crew members of an underwater drilling platform. This is how The Abyss was born.

Known for his perfectionism, Cameron was dissatisfied with the early version of the script, so he asked science fiction writer Orson Scott Card for help. Card was to create a novel that would deepen the themes presented in the script. Although initially reluctant to collaborate, as he himself said, he was not in the habit of taking part in adaptations, Cameron’s name had an impact. After meeting with the director, he wrote the first three chapters of the book, which dealt with the marriage of the main characters. This story could help the actors better immerse themselves in their roles.

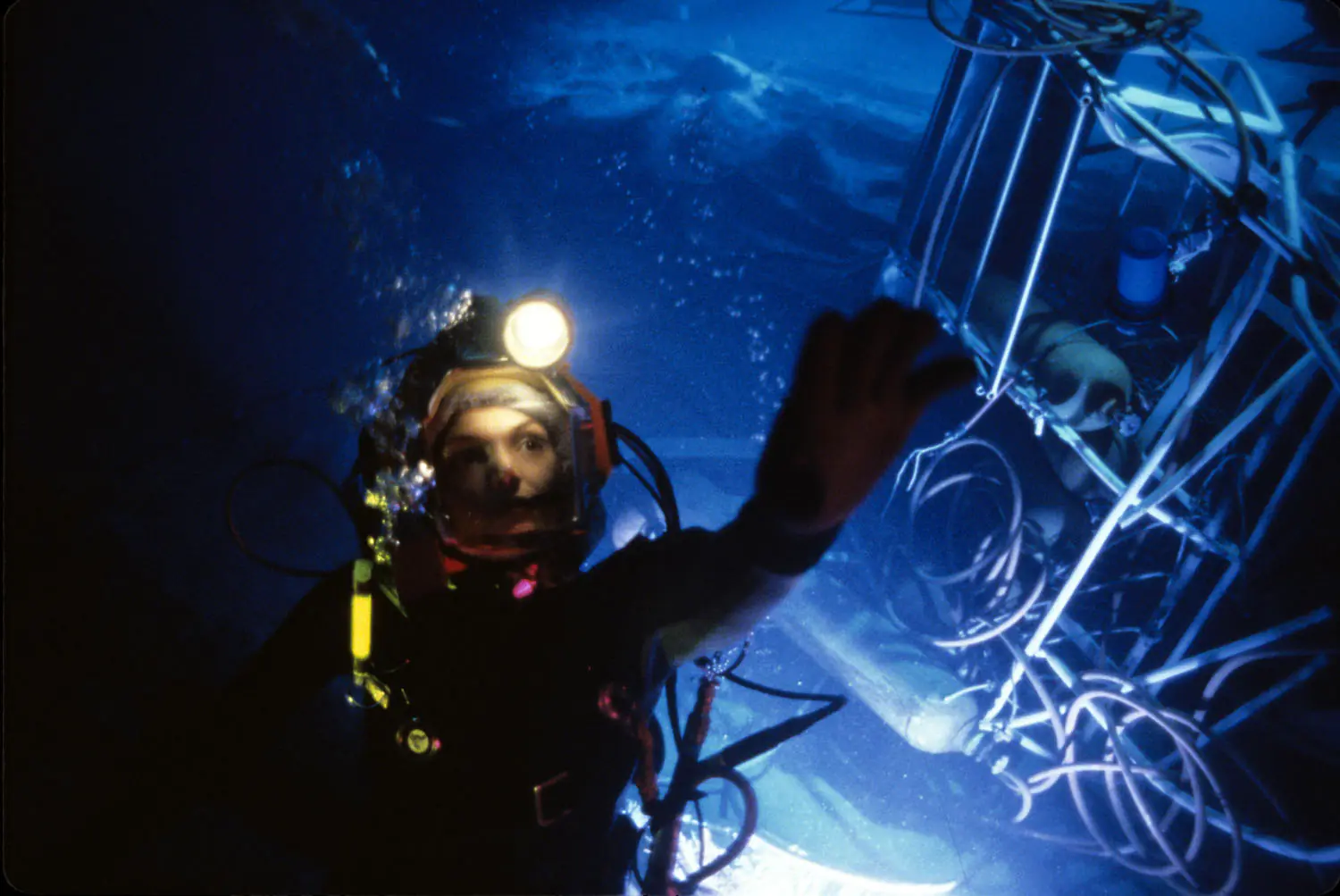

The director’s stamp of perfectionism and megalomania was evident in the realization of the scenes. Cameron was determined to give the underwater scenes the maximum realism. However, the conventional way of filming such scenes (like shooting in slow motion on a set filled with smoke or using stunt divers) didn’t convince him. Cameron had to have his own ocean and his own abyss, where his actors, after obtaining diving licenses, could swim at his discretion. He eventually succeeded when he found an unfinished nuclear power plant in Gaffney, South Carolina. In its two tanks, underwater sets were built in 1988 (which, interestingly, can still be visited today).

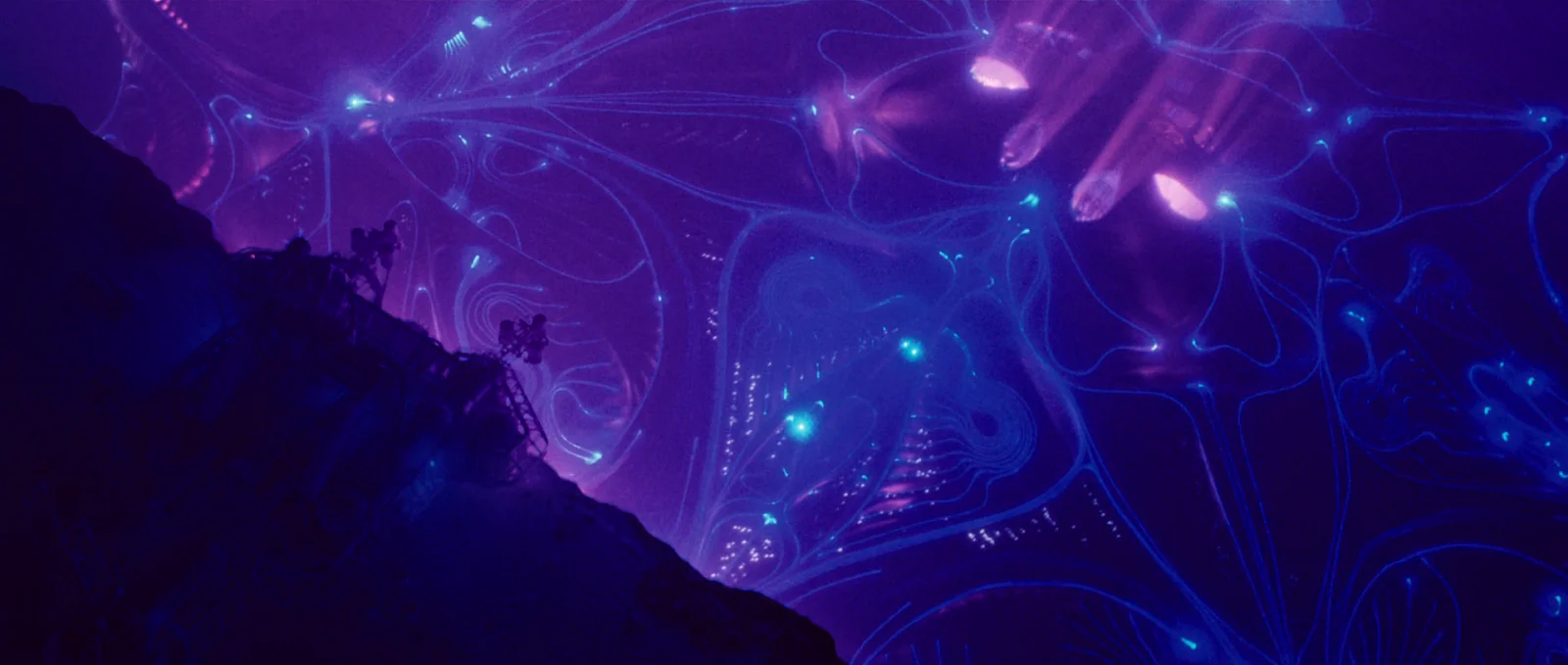

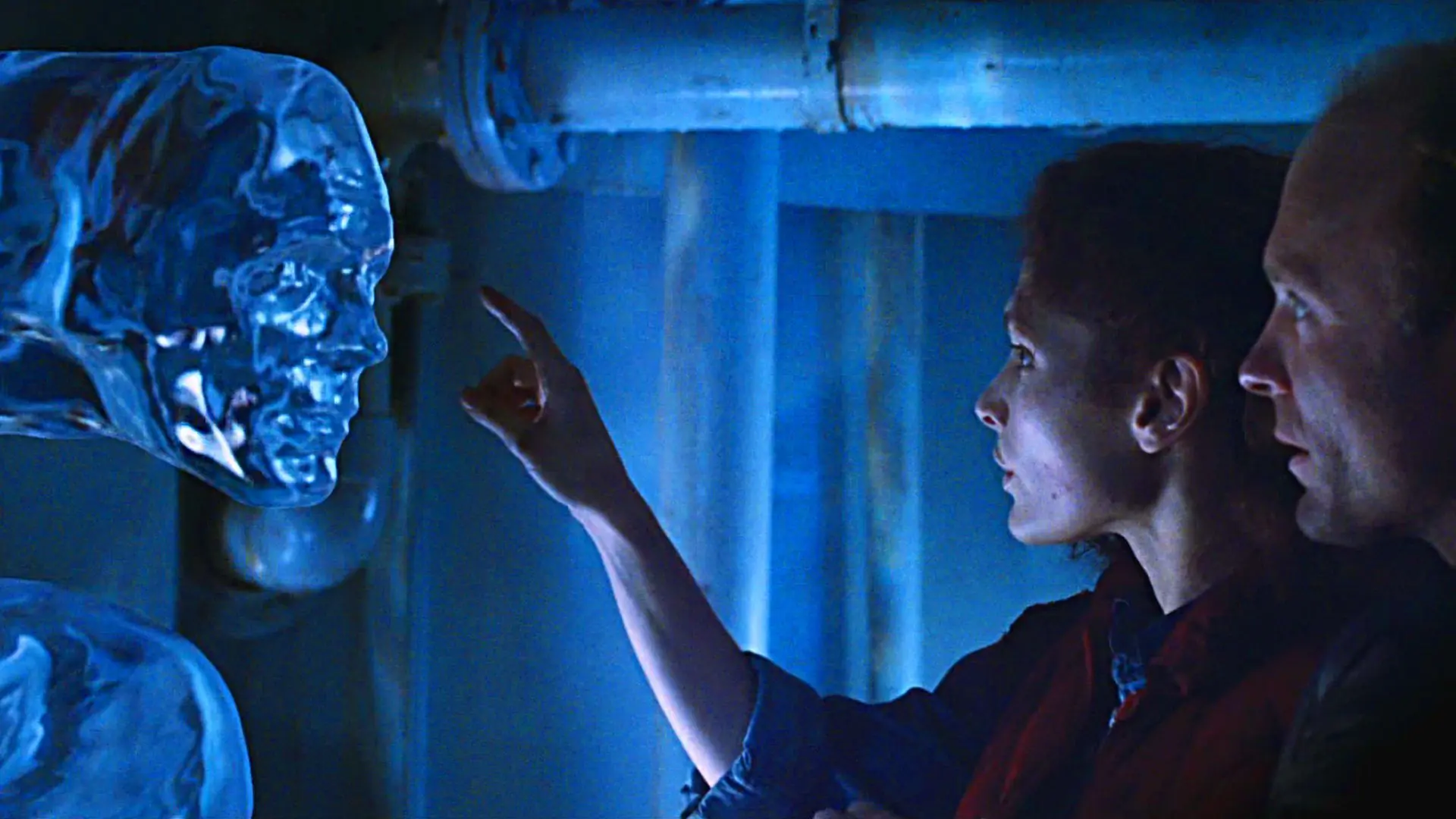

The risk paid off. Looking at the technical aspect of The Abyss, it’s hard to find any weak point, even almost forty years after its premiere. The set of the underwater drilling station and the design of the diving suits evoke a sense of realism – and that was the goal. Meanwhile, the amazing special effects for the time, some of the first CGI in history (with the participation of George Lucas’s famous company, Industrial Light & Magic), still take the breath away – especially the famous scene with the water ribbon, somewhat repeated years later (in a slightly different version) in Terminator 2. Looking at the Oscar nominations and awards received in almost all technical categories, one might say that while The Abyss works visually, it might not captivate the viewer with its plot or acting. Fortunately, this is a mistaken conclusion.

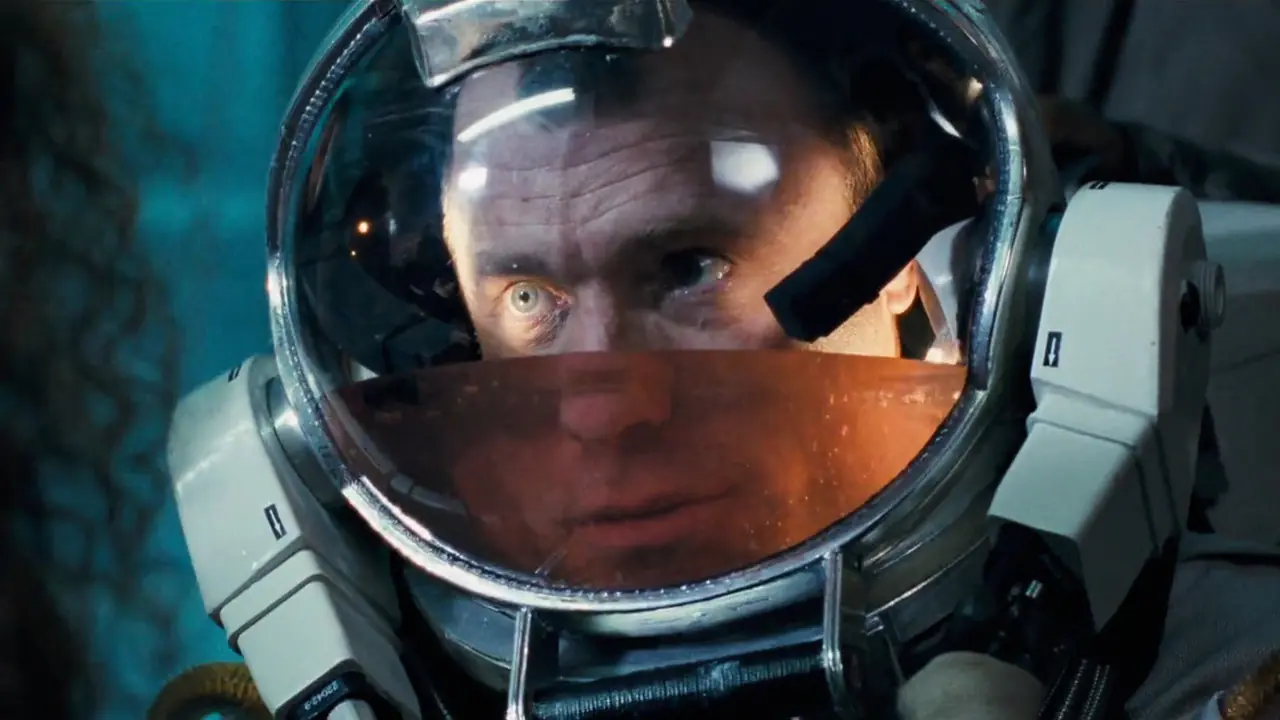

Both Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, as well as Michael Biehn, Cameron’s favorite, created full-blooded, credible, and memorable performances. I would even dare to say that some of their best roles. The paradox of their creations is that years later, they are not grateful to fate for being on the set of The Abyss. That’s because their involvement in the film nearly cost them their lives. Ed Harris, for instance, almost drowned while filming one of the scenes, and to this day, he refuses to publicly discuss the production process with Cameron.

Not only did the director refuse to use stuntmen, but he also didn’t rely on mannequins, which meant even the corpses were played by actors holding their breath – something that today might be seen as a sign of madness. In the scene where Bud drags Lindsey’s body underwater, it is Harris and Mastrantonio performing, not a stuntman and a mannequin, as one might expect. This constant flirting with fate and walking the line of human endurance led the crew working on The Abyss to quickly dub the work “The Abuse”. However, significantly, years later, Cameron himself recalls filming The Abyss as a nightmare, partly because… he too was at risk of drowning.

One could criticize Cameron for, while striving for staging realism, simultaneously neglecting some scientific aspects. These are issues that might not trouble the average popcorn eater but would certainly bother the discerning fan of science fiction. I’m talking about situations related to a water pressure, which in one moment crushes the bathyscaphe like a can, and in another, allows a diver to break the Guinness deep-sea record. However, one can overlook this if we consider that we are still dealing with science fiction, moreover taking on the first contact between humans and an alien race from space. A race for which this kind of pressure seems to serve exceptionally well.

The tone of the encounter between humans and aliens here is entirely different from what Cameron suggested in his previous film. While Aliens expresses concerns that contact with aliens harbors many mortal dangers, in The Abyss, an optimistic result of meeting other forms of life is promoted. Cameron, therefore, went in a similar direction as his colleague Steven Spielberg in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Although the director’s cut of The Abyss, with its extended climax, significantly broadens the theme of contact with aliens with a humanitarian and pacifist message, I remain among the supporters of the theatrical version, much subtler in its message, using ambiguity as a tool to build an aura of mystery around the central theme.

It is worth dispelling one myth at this point. It might seem that the 20th Century Fox studio pressured Cameron to shorten the film, fearing that the audience would not want to watch a nearly three-hour underwater spectacle in the cinema. This could put the high, for those times, $50 million budget at risk of a financial flop. However, it turns out that Cameron had final cut rights, meaning he had the right to make the final decision on the film’s cut, and it was he who decided that the famous alternative ending would be available only in the extended version. That was a good decision.

Alan Silvestri, who composed the music for the film, was able to give the story the proper weight and grandeur. What still delights in The Abyss after all these years and encourages a repeat viewing is mainly its unique underwater atmosphere. For me, it is above all a fascinating adventure to the deepest, darkest ocean depths, a creative combination of the ideas in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and the ambitions of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Here, man is, as often happens in Cameron’s work, once again pitted against technology, which, on one hand – like a true element – brings opportunity, and on the other, leads to destruction.

But The Abyss is also a small drama in a vast ocean. It is primarily a story about making up for lost time, reworking a marriage headed for inevitable collapse. The oceanic depths seem to be the best metaphor for the relationship between Bud and Lindsey. Yet, somehow, they both find a chance for themselves; they wake up to life, filling their lungs with air and love. Yes, I want to emphasize this – with all its incredibly impressive visuals, The Abyss is also one of the most touching science fiction films I have ever seen.

Paraphrasing Nietzsche’s quote, I can say that when I look into The Abyss years later, it is this very Abyss that looks even more deeply into me.