SALTO. A Cult Classic, Neither Simple Nor Straightforward

It is not a simple or straightforward film, and to understand the message of the filmmakers of the 1960s, one must delve into the history of the Polish Film School.

The cinema of Wojciech Jerzy Has, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, Andrzej Wajda, and finally Tadeusz Konwicki decisively broke away from the socialist realism style, introducing new generational, aesthetic, and ideological content into Polish films. They focused mainly on analyzing the consequences of war and debating national attitudes and myths. This approach was also applied using Konwicki’s literary achievements, creating a romantic and individualistic character, Kowalski/Malinowski, a small town as a miniature of Poland, while breaking taboos and the propaganda-driven one-sided interpretation of World War II. Salto

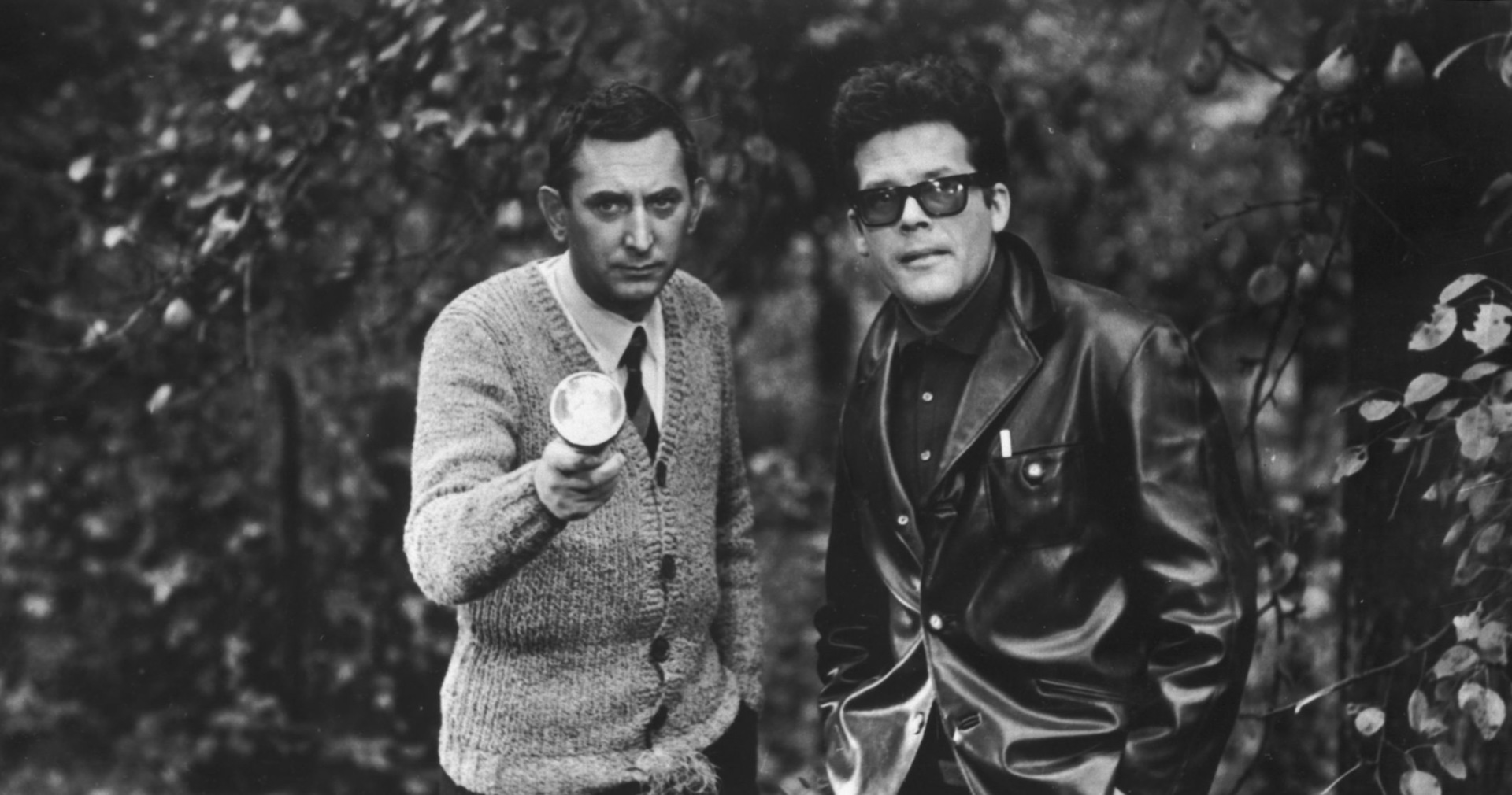

Salto opens with a scene of a man jumping from a speeding train somewhere in the wilderness of the Polish countryside. A rebellious, mysterious hero with the face of Zbigniew Cybulski flees to a provincial, idyllic town in the middle of nowhere. The newcomer alternately introduces himself as Kowalski and Malinowski. He is escaping from “bad people” and seeking refuge in a place where he allegedly spent the years of the occupation. The man begins to tell the townspeople incredible stories of his life. Though they sound unbelievable, it is suspected they contain a grain of truth. The setting itself, which seems both real and dreamlike, supports this.

All the residents are like puppets merely playing their assigned roles. Consequently, Kowalski, who carries an air of deception, appears to be the only real person. He freely manipulates emotions, easily reading thoughts and worries from the townspeople’s faces, exposing them. The mystifying, seeking pity and death stranger, however, has something to convey to the townspeople. He heals sick children like Christ, predicts people’s futures, and most importantly, can make them dance to his tune. Opinions are divided. Is the mysterious stranger a mere common liar, or a Messiah who has come to awaken a town mired in stagnation?

The town is bathed in an oneiric vision, similar to the town from Konwicki’s novel A Dreambook for Our Time. The presence of the new guest awakens the local community, once full of somnambulists, anemics, and lackluster people. His words fall on fertile ground. Each resident is a grotesque embodiment of Polish stereotypes. Stepping forward is the envious, proud artist and poet. There is also a widow fortune-teller, a proud veteran of wartime exploits, a reclusive Jew Blumenfeld, the enigmatic Helena, and the good-hearted Host. All these people gather for an anniversary celebration.

There, inspired by the presence of the mysterious liar-savior, they remove their blinders and cut their strings. They learn the truth about themselves, open up to each other, and awaken from a deep sleep. Kowalski/Malinowski takes control of the souls of the townspeople, making them dance. The association is clear. Konwicki revives the motif from Stanisław Wyspiański’s The Wedding, dancing to the music of Wojciech Kilar and stirring the characters into a new, frenzied dance. The townspeople, like in a trance, once again lulled, dance to the choreography of Kowalski/Malinowski. The time for redemption has come. It is an attempt to exorcise the nation, represented by the gray inhabitants of the small town. The savior himself satisfies all his senses, all his desires. He promises more than he can deliver, and through his confusion and inability to reveal himself clearly, he destroys his own mystification.

How will the nation, upon awakening, treat the new savior? Will they accept his gifts, salvation from stagnation, or stone him for his lies and for being as flawed as they are? Perhaps there was never a savior, only a fraud and a fugitive. Is Salto an attempt to awaken the Polish nation trapped in a fatal dream, seduced by socialism? Perhaps it is a polemic with idealized Polish myths, legends of romantic individualist-saviors. It is also possible that spirits hover over the village. Soldiers who have long captured and killed the main character, Blumenfeld is an actor who has long since passed away. All the inhabitants are phantoms, trying desperately to rise from their dead knees, unable to find rest and peace. Konwicki does not provide clear answers. He leaves many ambiguities and open fields for personal interpretation.

The film is a deeply allegorical story, but also a rich sociological observation of the nation. Great symbols freely intertwine with the commonplace reality of the village. Salto is closest to poetic cinema, rich in puzzles and ambiguities. The action moves slowly, and the word carries the most weight.