Dickens’s A CHRISTMAS CAROL: An Iconic Story Scrutinized

For some, Christmas with family is the most awaited moment of the year, while for others, it is a few-day nightmare that intensifies in direct proportion to the number of glasses of grandma’s liqueur emptied by the household members. However, while family gatherings are somewhat unpredictable, because you never know in which direction the verbal chess match over the table will go, media during Christmas are like a rock or a solid foundation on which we can build our Christmas experience. Home Alone, Santa Claus Is Coming to Town, Last Christmas, and All I Want For Christmas Is You have over the years become artifacts as important as Christmas paty. We may cringe at such a statement, swear that it doesn’t concern us, but after a short soul-searching, most of us will probably come to the conclusion that without this whole Christmas pop culture routine, it would be a little sad, uneasy, strange. A Christmas Carol

The celebration of Christmas is a form of ritual, and rituals require repetition. This is manifested both in the sacred sphere and in the commercial and entertainment atmosphere created around one of the most important moments in the Christian calendar. It is for this reason that many cultural creations made with Christmas in mind easily permeate the consciousness of the mass audience. Their schematism is not a flaw this time but the fulfillment of certain specific needs that fit into the broad ethos of Christmas as a time when it is worth stopping to find time for oneself and others. One of the iconic stories that has significantly contributed to the creation of the modern image of Christmas is undoubtedly A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. The story, published in 1843, remains one of the most frequently quoted and adapted Christmas narratives to this day. For this reason alone, it is worth tracking how it has moved through the world of cinema.

From the Lumières to World War II

The first public screening of the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph took place on December 28, 1895, in the Indian Salon. This date is commonly considered the beginning of cinema. By the time the workers from their Lyon factory appeared on screen for the first time, Charles Dickens had been dead for twenty-five years, and A Christmas Carol was celebrating its fifty-second anniversary. The text of the English author had already been successfully staged on theater stages for years, but cinema in the 19th century was not yet ready to tell complex stories. Of course, the early 20th century did not change much in this regard, but as the new century began, filmmakers gradually began to move away from documentary conventions and experiment with narratives. Cinema sought to create its own language that could reach audiences as effectively as literature and theater, which required a confrontation with these media and the classic stories within them.

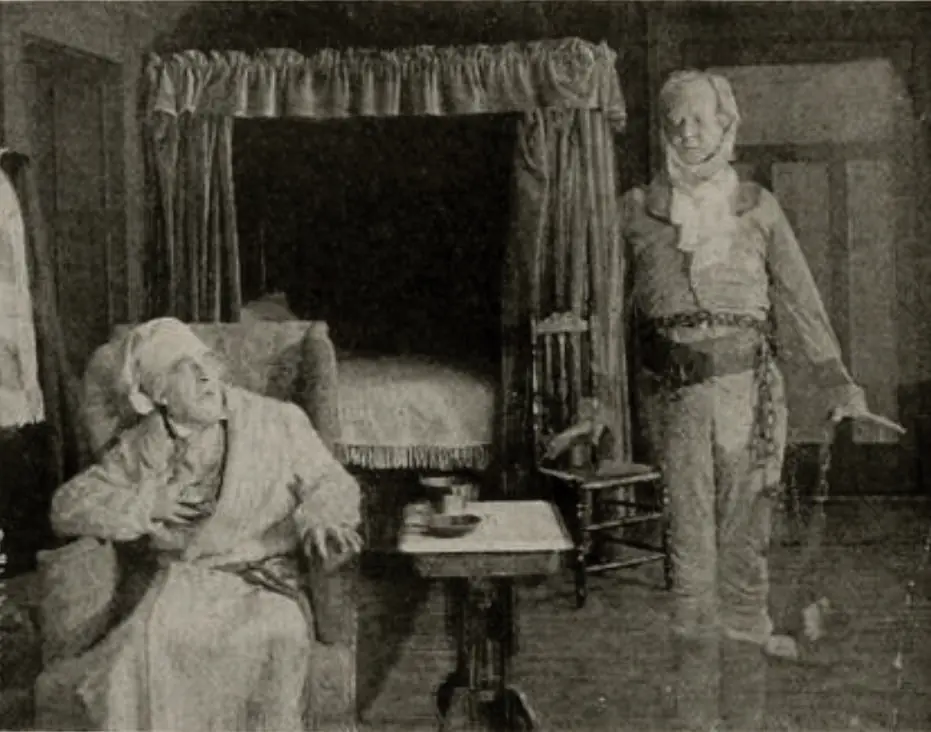

The first romance between A Christmas Carol and cinema took place as early as 1901, when Walter R. Booth, a specialist in magic tricks, decided to present Dickens’ text in under five minutes. Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost was considered a lost film for many years. However, after years, fragments were found in a box containing a professional collection of film reels belonging to a wealthy family. Thanks to this discovery, viewers can now watch exactly three minutes and twenty-seven seconds of the first adaptation of A Christmas Carol. Fortunately, among these fragments, the technical tricks of Walter R. Booth were preserved, including the appearance of Marley’s Ghost in place of the door knocker on Scrooge’s door. Although such effects may seem amusing today, it is important to remember that only a few years earlier, people were fleeing the cinema in fear of being run over by the train filmed by the Lumière brothers. Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost was primarily based on the play by John Copeland Buckstone, which, in the early 20th century, was the most popular stage adaptation of Dickens’ text. Unfortunately, the names of the first actors to portray Ebenezer Scrooge on film have been lost to history. It is also worth mentioning that Walter R. Booth, the film’s director, five years after this film’s release, created the first British animation titled The Hand of the Artist (1906).

In 1908, Scrooge crossed the Atlantic to reach the Essanay Studios in Chicago. The American studio is mainly remembered in film history for having taken in a young Charlie Chaplin at the time when he left Keystone Studios, managed by the legendary comedian Mack Sennett. In 1908, however, the studio was still in its infancy, and A Christmas Carol was meant to be a hit that would help expand its operations. Thanks to it, Tom Ricketts became the first film Scrooge known by name. Unfortunately, the film itself has been considered lost, and all information about it comes from the contemporary magazine The Moving Picture World, which published a note about the cast and a detailed description of the film’s scenes upon its release. The same magazine praised the adaptation of A Christmas Carol to the heavens, which raises the question of whether the first American adaptation of Dickens’ text also contributed to the creation of one of the first sponsored articles in film trade magazines.

As early as 1910, Thomas Edison saw the potential of the Christmas classic and, in between filing patent applications and lighting bulbs, decided to shake up the film business as well. The interpretation of the story of Scrooge’s transformation created at his request is the first full-length screen adaptation of A Christmas Carol that has been preserved. The film, directed by J. Searle Dawley and starring Australian Broadway actor Marcus McDermott, lasts just under fourteen minutes.

The 1913 Scrooge and the 1914 A Christmas Carol perfectly highlight how dynamically cinema evolved over nearly two decades. In both films, the roles of the bitter old men who experience the horror and magic of Christmas are played by established theater actors. In the first film, it is Seymour Hicks, and in the second, it is Charles Rock. Just a few years earlier, it was considered impossible to reconcile the world of theater and cinema from an actor’s perspective. Those who performed on stage considered film to be carnival entertainment, suitable only for poorly educated crowds. Acting before a camera was regarded as a low-level craft, good for amateurs and people interested only in earning a few pennies. A dramatic transformation also took place in terms of technique and the skills required to use moving images. The 1914 film lasted about twenty minutes, while the 1913 one was nearly forty minutes long, which, compared to the barely five-minute Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost from 1901, must have been impressive. The creation of film reality (sets, lighting, etc.) in these two films went far beyond the level of their predecessors.

All the known adaptations of A Christmas Carol made between 1901 and 1914 came from English-speaking countries (the United States or the United Kingdom), so it is easy to understand why the outbreak of World War I temporarily halted the slowly spinning carousel of new adaptations of Dickens’ text. The costs associated with waging war and the departure of men, who at that time had a monopoly on the film business, must have had an impact on its condition. Between 1914 and 1922, only one version of A Christmas Carol was made. In 1916, it was shown under the title The Right to Be Happy, which, in the context of the situation in the world at the time, became quite a poignant manifestation.

In 1922, the first post-war adaptation of A Christmas Carol was made, which is now considered lost. Just a year after this adaptation, the cast of actors portraying Scrooge was joined by World War I veteran Russell Thorndike, who is better known in history as the author of the popular (in the UK) series of novels about Dr. Syn. The 1923 version, despite the decade separating it from the 1913 and 1914 adaptations, did not offer much innovation. It wasn’t until 1928 that a real novelty appeared with Scrooge, which was shown with a soundtrack synchronized with the film through Phonofilm technology, marking a symbolic moment of saying goodbye to the silent film era and entering the world of sound cinema. Unfortunately, the film met the same fate as Dickens’ ghosts — it disappeared.

The first fully sound film adaptation was Scrooge from 1935. Interestingly, in this version, Seymour Hicks, who had played Scrooge in the 1913 version, reprised the title role after a gap of twenty-two years. Hicks, who could likely hold a Guinness World Record for playing Ebenezer Scrooge more than any other actor, spent a significant part of his career performing the role on British theater stages. Moreover, Hicks portrays both the old and young Scrooge in the film, which is a rare occurrence in the history of adaptations of Dickens’ text (it is said to have happened only three times, but who’s counting!).

In 1938, the last pre-World War II adaptation of A Christmas Carol was produced. This film, made by MGM, is today considered one of the most recognizable adaptations of Dickens’ work from the pre-war era, largely due to its status as a Christmas classic in the United States, upon which many later creators based their versions. The film was marketed as an example of family cinema, perfectly in line with the studio’s intentions for the production. As such, the 1938 version omits many elements that might scare, bore, or be too difficult for younger viewers to understand. Even the ghosts are reduced to brief appearances, with most of their presence limited to their voices. The role of Scrooge was played by Reginald Owen, who replaced the first choice, Lionel Barrymore, due to the latter’s worsening arthritis. However, Barrymore still contributed to the production, lending his voice to the official trailer for the film, directed by Edwin L. Marin.

The Path to Modernity

Jerzy Płażewski once said that silent cinema is a mystery we will likely never fully understand. The number of lost films or productions we only know from brief mentions in the press or notes found in archives is immense. If we were to recover even a fraction of the films that have vanished in the tumultuous currents of history, we might have to rewrite film history altogether. In the case of A Christmas Carol, we see just how many versions have not survived to this day. Many others, no doubt, are only known to those who will never have the chance to share their memories of watching them. This situation, however, makes it easier to systematically organize the existing material, which is why the section of the text dedicated to pre-1939 productions is so precise

After World War II, cinema began to grow at lightning speed, with the help of its younger sibling—television. Initially, there was no technology to record signals broadcast over the airwaves, meaning live TV programs were lost forever. This fate befell, for example, the early televised theater, which included a 1943 adaptation of A Christmas Carol, aired by an American TV station.

Contrary to what one might expect, Dickens’ story didn’t appear in theaters too often. After 1945, with the rapid growth of interest in television sets, most productions focusing on Ebenezer Scrooge’s Christmas transformation were made for that medium. As a result, it’s impossible to count all the versions of the story that have emerged on the global film map since then. Even if it were possible, it would be pointless to do so, as much of the television content produced for Christmas was made hastily, primarily to fill the holiday TV schedule and make money from advertisements. Therefore, in this part of the text, I will present only a subjective selection of the most interesting (for various reasons) productions that have brought Dickens’ A Christmas Carol into the modern era

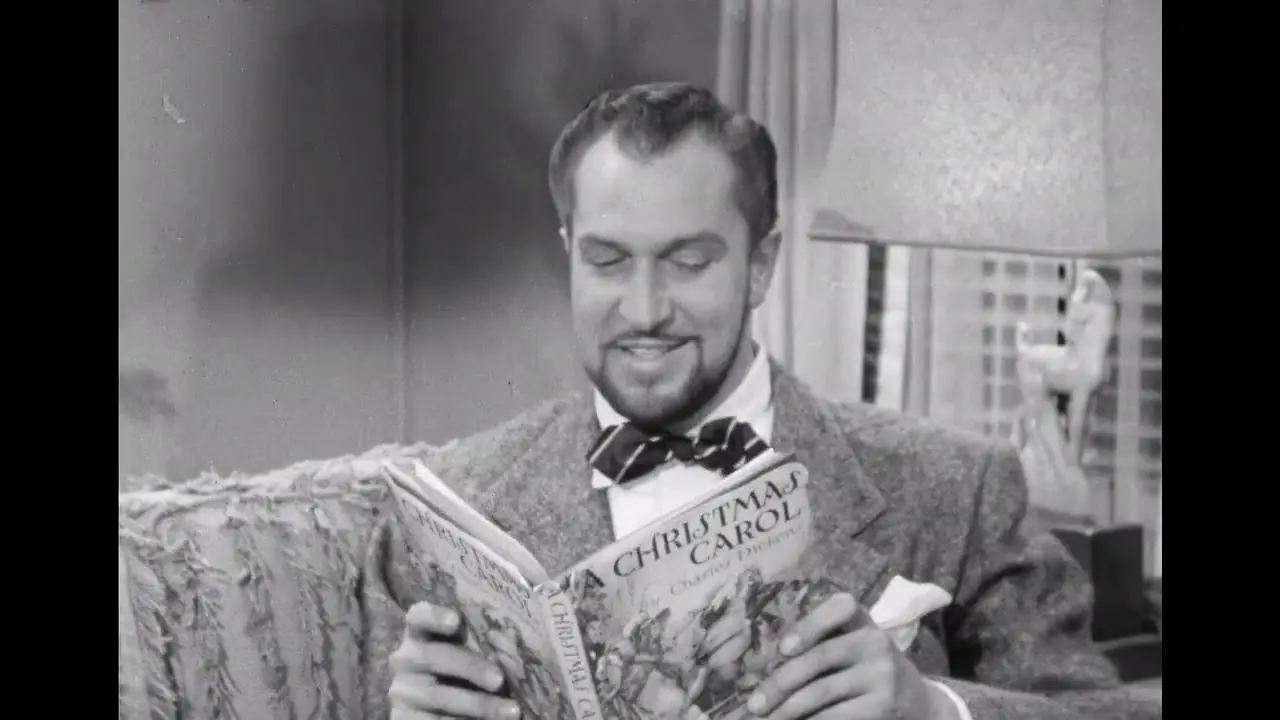

The 1947 version of A Christmas Carol is notable primarily for one reason: it marks the screen debut of David Carradine, who was eleven years old at the time, alongside his father, John Carradine. This is charming considering his later film career. A bit more can be said about the half-hour television version from 1949. Sponsored by Magnavox, a major player in the American RTV market at the time, this production was designed to promote their television sets. As a result, it became one of the first such advertising efforts. The 1949 version may also interest James Bond fans, as a nine-year-old Jill St. John, who would later play the girlfriend of Agent 007 in Diamonds Are Forever, made her acting debut as one of Scrooge’s clerk’s daughters.

In 1951, Brian Desmond Hurst directed Scrooge, based on A Christmas Carol. Among many critics, it is considered by some to be the best film adaptation of Dickens’ story. Although it achieved status as a Christmas classic in the United States, where it was repeatedly aired on TV, released on VHS and DVD, and even colorized in 1989, the film initially provoked strong reactions and faced difficulties in distribution. This was mainly due to the filmmakers’ decision to create a more serious version of the story, in stark contrast to the lighthearted, family-friendly MGM version from 1938. After the success of the 1938 adaptation, Universal Pictures saw the purchase of the British version as a cost-effective move. The film was initially planned for screening at a Christmas party at Radio City Music Hall in New York, but the organizers rejected it, deeming it unsuitable for the festive atmosphere. Universal agreed with this opinion, and A Christmas Carol by Hurst was ultimately released in American cinemas during Halloween instead.

One of the most interesting and unusual variations of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is undoubtedly the 1964 television adaptation A Carol for Another Christmas. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, this is the only production made by the director for the small screen. Moreover, it carries all the hallmarks of propaganda cinema. The funds for the adaptation were provided by the United Nations, which in the 1960s launched a program to educate and persuade people of the importance of the organization’s ideals. In this version, Scrooge is a cynical American capitalist who uses his influence to try to convince the United States to abandon policies aligned with the principles of the United Nations. He argues that the U.S. should not be involved in the problems of other nations, that taxpayer money should fund the atomic program, and that any signs of tolerance towards other cultures are harmful, as evidenced by his attempt to prevent cooperation between Polish and American universities. In his journey, Scrooge is confronted with a vision of the world that has rejected the ideals of the UN. Naturally, the images presented to him during his travels lead to his transformation. Sterling Hayden plays the role of Ebenezer in the film, but the most intriguing casting choice is Peter Sellers, who portrays the leader of one of the worlds visited by Scrooge. This marked Sellers’ first film after a near-fatal overdose of vasodilator medication before a planned romantic evening with his partner, which caused him to suffer eight heart attacks within three hours.

In 1970, the British musical Scrooge received four Oscar nominations, and Albert Finney, who played the title character, won a Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Comedy or Musical. In 1984, George C. Scott, known for his iconic role as General Patton in Franklin J. Schaffner’s Patton, took on the role of the bitter old man for a television production. Interestingly, the director of this film, Clive Donner, had been the editor of the 1951 adaptation (with Alastair Sim in the lead role). The television production was a major success, which prompted distributors to release the film in cinemas in the UK.

The year 1988 brought one of the most popular variations of A Christmas Carol, Scrooged, directed by Richard Donner, with Bill Murray playing a film version of Scrooge. Scrooged transposes Dickens’ classic tale into the cutthroat world of television, where the only thing that matters is money. However, the magical atmosphere of Dickens’ story didn’t quite resonate with Murray and Donner, who, to put it mildly, struggled to communicate with each other. In interviews after the film’s release, Murray openly expressed his frustration with the fact that the director didn’t allow him much creative freedom and wouldn’t let him develop his character in the way he had hoped. Despite these tensions and the mixed critical reception, Scrooged remains a highly recommended film. After all, it’s Donner, Murray, and the 1980s—what more could you want?

In terms of live-action adaptations, another noteworthy version of A Christmas Carol premiered in 1999. In this adaptation, Patrick Stewart not only played the lead role of Scrooge but also served as the producer. The television film received an Emmy nomination for Best Cinematography. Its style and script are heavily inspired by the 1951 adaptation, with a modern take on the timeless Dickensian themes.

A Christmas Carol in the World of Animation

Given its family-friendly nature, A Christmas Carol has also found its place in the world of animation. However, many of the animated adaptations of Dickens’ tale are not of high artistic quality, often being simple, quick cartoons filling the slots of Christmas programming aimed at children. The story of A Christmas Carol in animation begins around the 1960s, with a notable adaptation featuring Mr. Magoo, a character from the series created by United Productions of America (UPA) in 1949. Mr. Magoo, who suffers from severe myopia, became a precursor for many other animated characters to take on the role of Scrooge. By 1979, the Looney Tunes gang, led by Bugs Bunny, created their own version, followed by Mickey Mouse and his friends in 1983. Over the years, other beloved animated characters, such as the Flintstones, the Jetsons, and even the Muppets and the Sesame Street characters, have joined in the tradition. Of these adaptations, the Disney version and the one with Kermit the Frog and the Muppets stand out.

In terms of original animated adaptations, there are a couple worth mentioning, particularly the 1971 and 2009 versions. The 1971 version, directed by Richard Williams, is notable for its high-quality animation and distinctive style. Williams, who would later go on to direct animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), learned the craft by observing animation legend Ken Harris, who worked on iconic pieces like the opening credits of The Pink Panther (1963) and the 1966 How the Grinch Stole Christmas. Interestingly, the voices of both the Ghost of Marley and Scrooge in the 1971 film were provided by the same actors who had voiced them in the 1951 live-action version of Scrooge.

The 2009 adaptation, directed by Robert Zemeckis, is a computer-generated animation that remains the most expensive film version of A Christmas Carol to date (maybe next to Spirited, 2022). Known for its cutting-edge motion capture technology, the film features Jim Carrey as Scrooge, as well as several of the ghosts, showcasing a highly detailed and visually striking approach to Dickens’ classic story.

The text describes only a fraction of A Christmas Carol ‘s presence on both the small and big screens, but it is a fairly representative segment. Some works, such as Scrooge in the Hood (2011), in which the titular character struggles not only with ghosts but also with a Jewish mafia who stole the prostitutes he oversees, have been omitted from this discussion. However, such “gems” are a topic for another article. Merry Christmas!