PHARAOH. A masterpiece in the shadow of the pyramids

The intelligent exploration of national myths, the departure from socialist realism, and the relentless struggle with the demons haunting the imaginations of those who remembered the hell of World War II ceased to appeal to the members of the Polish United Workers’ Party. The 1960 Central Committee resolution defined the kind of films that should be made in a country that supported the only correct Soviet idea of the brotherhood of Eastern Bloc nations. Of course, no self-respecting Polish filmmaker took these guidelines seriously, but struggles with censorship necessitated a change in tactics.

They dealt with it in various ways. The first was to stop looking back and focus on contemporary problems. Films emerged that, following the literary trend of small realism developed in the 1960s, began to abandon deep psychological portraits and metaphorical rebellion against life under the yoke of communism. Not all productions stemming from this trend were automatically artistic failures. Films like See You on Sunday by Stanisław Lenartowicz, Who Knows by Kazimierz Kutz, and the excellent Parting by Wojciech Jerzy Has demonstrated that it was possible to create in this manner without a significant loss of film value. The second path circumventing censorship traps led through the intimate experiences of creators who crafted thoroughly auteur and personal cinema. The greatest achievement in this area was perhaps Tadeusz Konwicki with his Salto. Neorealism inspired Wajda and his Innocent Sorcerers, and with originality and consistency in building a psychological drama, at times reaching the intensity of a thriller, young Roman Polański amazed everyone with his Knife in the Water. Thanks to the development of production and technical capabilities, Polish cinemas also found space for grand historical spectacles, which were intended to compete with the relatively new yet rapidly developing medium of television. Pharaoh

However, Poles did not treat history the same way as many of their Western colleagues. Their films meticulously characterized the times they depicted. Even when the ultimate tone of the film was far from grave seriousness, and highly adventurous characters like Wołodyjowski were meant more to entertain viewers than provoke deep reflection, the meticulousness of epoch representation was very high. Films like Knights of the Teutonic Order, The Saragossa Manuscript,” and Ashes clearly stood out against American or Italian films made with similar grandeur. The convention of the grand historical spectacle, based on a respected literary work, was also embraced by one of the most outstanding and, in my humble opinion, still insufficiently appreciated creators in the history of Polish cinema – Jerzy Kawalerowicz. His Pharaoh, based on the prose of Bolesław Prus, transported viewers to ancient Egypt. However, it did not aim to awe them with the smooth visage of Cleopatra or dazzle them with the glittering treasures of the priests, although these elements appeared in Kawalerowicz’s film. In the director’s and his screenwriter Tadeusz Konwicki’s interpretation, Prus’s novel turned into a universal tale about power, comparable to works like Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood.

Walking on scorching sand

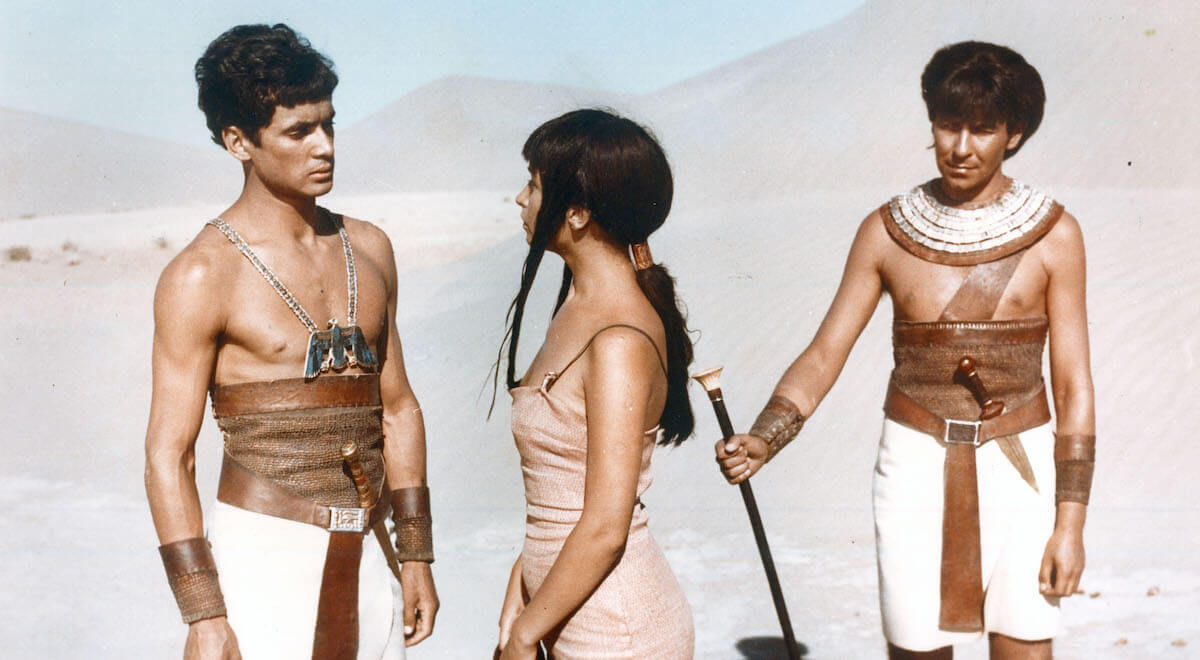

The production of Pharaoh lasted three years and was an enormous undertaking for its time. Filming took place on three continents – Europe, Asia, and Africa. Almost all desert scenes were shot in today’s Uzbekistan, on the Kyzyl-Kum Desert. The sequences where the characters are against the backdrop of Egyptian pyramids were filmed in Giza, and there are no post-production tricks to merely imitate the characters’ presence in the land of the pharaohs. The interiors of palaces, temples, and the priests’ labyrinth were built from scratch in the halls of the Łódź Film Studio. For the production, an artificial island was created on Lake Kirsajty near Giżycko, decorated with exotic vegetation to become the setting for the scene of sailing down the Nile. Filmmakers also worked in the Błędów Desert.

The most colorful stories about the production naturally come from the five-month stay on the Uzbek desert. The tales of bloodthirsty phalanx spiders that attacked people with aggressive jumps from up to five meters away are legendary. These desert arachnids, called solpugids, are rather timid towards humans and not very pleasant-looking creatures, usually measuring no more than a few centimeters, although some can reach up to several centimeters. A few of them may indeed have gotten among the masses of extras, but stories of terror and their venomousness can be attributed more to campfire tales. Vipers posed a greater threat, but the most serious adversary was not any living organism. Kyzyl-Kum devastated people due to high temperatures, which could heat the sand to between 60 and 80 degrees Celsius. Considering that a large part of the cast, due to historical accuracy, was forced to move barefoot on the desert, the sun indeed became a formidable opponent. Not only people but also film tapes had to be protected from its rays and the temperature they generated. The filmed material had to be stored in constantly cooled boxes, as it would be destroyed in regular containers.

During the premiere of the digital reconstruction of Pharaoh, Witold Sobociński, who served as the camera operator, spoke about the truly stunt-like feats forced by the situation during filming. The lack of advanced technical equipment and all kinds of image stabilizers forced the crew to creatively handle the sophisticated shots in the film. Sobociński recalls that he often replaced cranes and platforms with the help of obliging Soviet soldiers, who sometimes agreed to let him onto the open back of a truck and, with a heavy camera, drive him across the desert at speeds of several dozen kilometers per hour, facing backward. Speaking of Soviet soldiers, it’s worth mentioning that they played the role of extras populating Ramses’s army. They are also likely the authors of the solpugid myth, as in travel reports, it turns out that Russians stationed in areas inhabited by these creatures often called them phalanxes.

All the hardships were worth the final effect. Despite the passage of years, Pharaoh still stands out in terms of both technical and artistic achievement, being one of the most accurate film renditions of ancient Egypt. Years after its premiere, Kawalerowicz joked that he was almost sure he could write a doctoral dissertation in Egyptology without much trouble. The collaboration of Professor Kazimierz Michałowski and the Arab art historian and filmmaker Shadi Abdel Salam, who was one of Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s consultants on the 1963 production of Cleopatra, did not go to waste. Kawalerowicz and Konwicki’s meticulousness led not only to the perfect recreation of costumes, textures, and all the ornamentation related to the times of the pharaohs but also to somewhat more unusual undertakings, such as the Warsaw River Shipyard’s construction of a replica of an Egyptian ship based on sketches over four thousand years old.

In the shadow of the pyramids

Pharaoh is a unique position on the long list of texts created by Bolesław Prus. Throughout almost all his work, the author referred to contemporary issues, being a chronicler of the changes occurring during the era in which he lived. The story of Ramses XIII and his conflict with the priests is the only monumental historical tale in his repertoire, which for many years posed a challenge to Prus’s chroniclers. They tried to interpret it in many ways, but over time it came to be considered that through the example of Egypt during the pharaohs’ era, Prus wanted to tell a universal story about the problematic nature of power, thus addressing an almost Shakespearean theme. This interpretative thread inspired Kawalerowicz and Konwicki. Their film is not a literal translation of the literary language onto celluloid. The director and screenwriter managed to tell Prus’s story in such a way that it operates both as a minimalist, very personal drama of individuals and as a political metaphor provoking reflection on the historical mechanisms of power and the fact that over millennia, its nature does not significantly change.

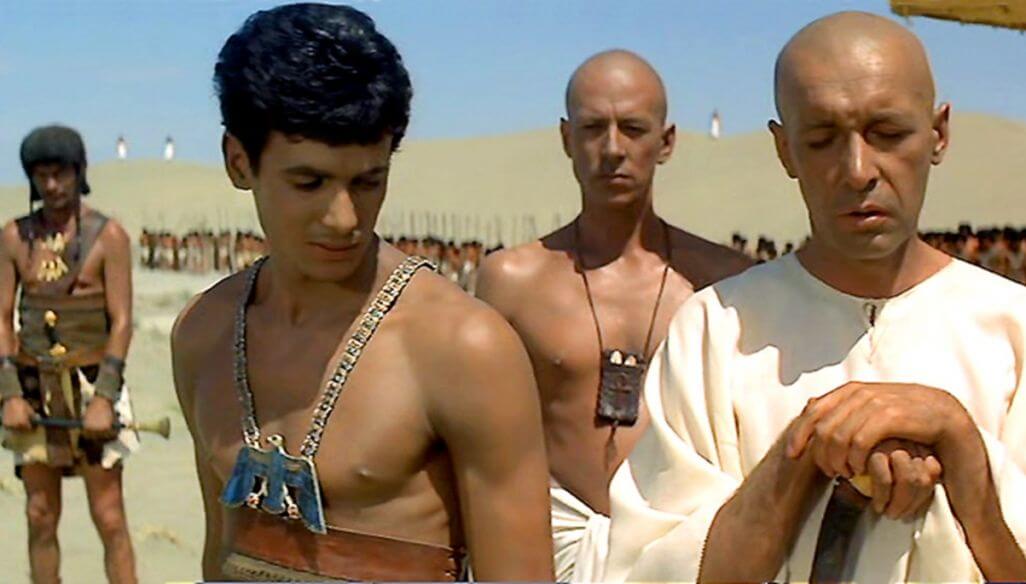

The clash between the idealistic Ramses XIII and the worldly-wise Herhor is a model situation of the collision between a new and old order. The curse of the former is the lack of knowledge about the processes that realistically underpin the state’s construction and social order. The flaw of the experienced elites is the cynicism associated with excessive faith in the established order. Konwicki and Kawalerowicz handle the novel material in such a way as to constantly confront conflicting views and force the viewer to choose a side in the conflict.

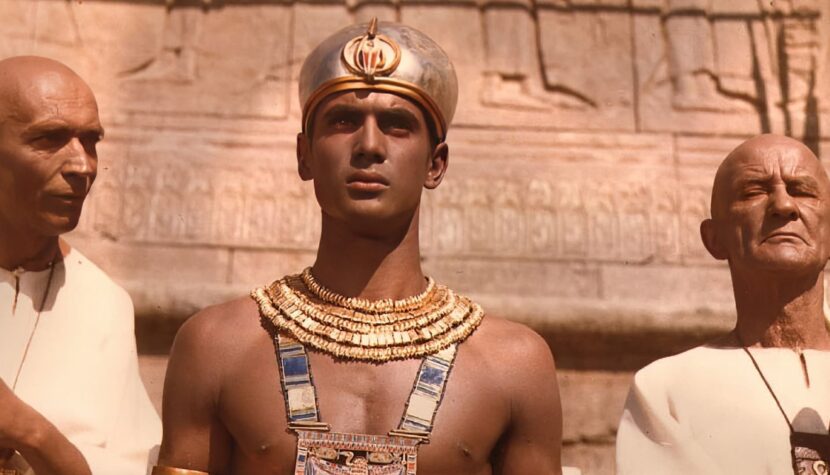

Theoretically, the matter seems simple. The unappealing appearance of the priests, exacerbated by their almost ascetic lifestyle, manifesting in a complete lack of emotions, facial expressions, and limiting themselves to uttering only the most important matters, makes them immediately suspect. Played by Jerzy Zelnik, the young Ramses XIII, full of vigor and eager to implement changes beneficial to the Egyptian people, is the clear antithesis of the clergy. Against the hierarchical world of palaces and temples, he appears as a source of life, the only element of normality. However, with each minute of the film, we realize that ideals and the motivation to overthrow the existing order and recreate the social structure anew cannot suffice to bring about a valuable revolution. The guiding principle of Ramses’s philosophy is the slogan that “there are no treaties for the weaker.” Enemies must be destroyed or intimidated, and power introduced through a military coup emphasizing the leader’s strength.

History teaches us that revolutions based on similar principles sooner or later transform into blood-drenched nightmares and lead to a new form of enslavement. The common people, subjected to pressure from opposing camps and the destructive whims of their leaders, are, as always, most disadvantaged. On the one hand, we have the priests aware of the destructive influence of wars and respecting cultural achievements, who, however, cannot distance themselves from their power-oriented attitude. On the other hand, a leader without knowledge and social awareness but brimming with youthful enthusiasm is ready to enforce his vision of the state, even at the cost of those he wants to rule. Kawalerowicz does not provide a simple answer, nor does he hand the viewer clear interpretative cues. We must make this decision on our own, knowing that it is impossible to do so without hesitation.

A highly intelligent script, enhanced by the extraordinary visual elements, has ensured that Pharaoh remains one of the best Polish blockbusters to this day. Thanks to the original use of the camera, often simulating the viewer’s participation in the events on screen (for example, a battle scene shown through the protagonist’s eyes), and a highly restrained color palette accentuated by the actors’ makeup, the filmmakers succeeded in making Pharaoh feel like an ancient tragedy.

All the lavish set designs take a back seat, while the labyrinths full of gold draw less attention than the emotional battles played out on the characters’ faces, which for some reason resemble masks. The culmination of this unique atmosphere is, of course, the final eclipse, during which the people gathered in front of the temple transform, due to the light—or rather its absence—into a faceless, terrified mass of creatures writhing in the sand. Such a suggestive visual metaphor for people’s dependence on power is unlikely to be found elsewhere in the history of cinema.