REPULSION. Polanski’s Claustrophobic Descent Into Madness

The eye does see, however, and in doing so it increasingly deviates from the gaze considered proper, healthy, and survival-oriented by the majority. Life seems to be the greatest value, and denying it an unforgivable crime.

Yet the dead rabbit neither looks nor sees, but it fulfills its function perfectly. It measures time for Polanski. It is a measure of growing disgust, guiding the viewer through a sparsely told story, gradually fueling emotions until the ultimate decay. Only Bergman in black and white could construct a film in such a way that the viewer felt a particular kind of existential disgust off-screen. Polanski in Repulsion has perfectly learned the master’s lesson.

It’s a somewhat distant association, but I remember the eye from Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, which similarly looked meaningfully at the viewer. In that gaze, there was a silent reproach that the replicants were given too little time, though even that was enough for them to look further than humans could in a lifetime. Yet, fireworks flashed in the pupil, suggesting that this way of seeing could be purified in humans. This dualistic ocularcentrism is absent in Polanski’s Repulsion. In his eye, only dry, formally planned credits roll – title, cast, photography, direction. The gaze is murky, the eyeball trembles, and only the subjective measure of time separates the eye’s owner from the planned explosion. The world will allow it, although it does not have to. But why shouldn’t it, since it is amoral, and humans mistakenly ascribe ethical value, personal traits, and supernatural abilities to it. This seemingly soulless reality is what Polanski will like to show throughout his filmography, continually entangling himself in considerations of how to find oneself in an environment where ‘there is emptiness beside the moon.’ How to fit one’s story, felt so vividly and passionately, into this empty space. The answer to what to do when it can’t be done remains open. Not withstand the disgust, go mad and attack, or, half-satisfied (or maybe not at all), wait for natural death with clenched teeth and humility?

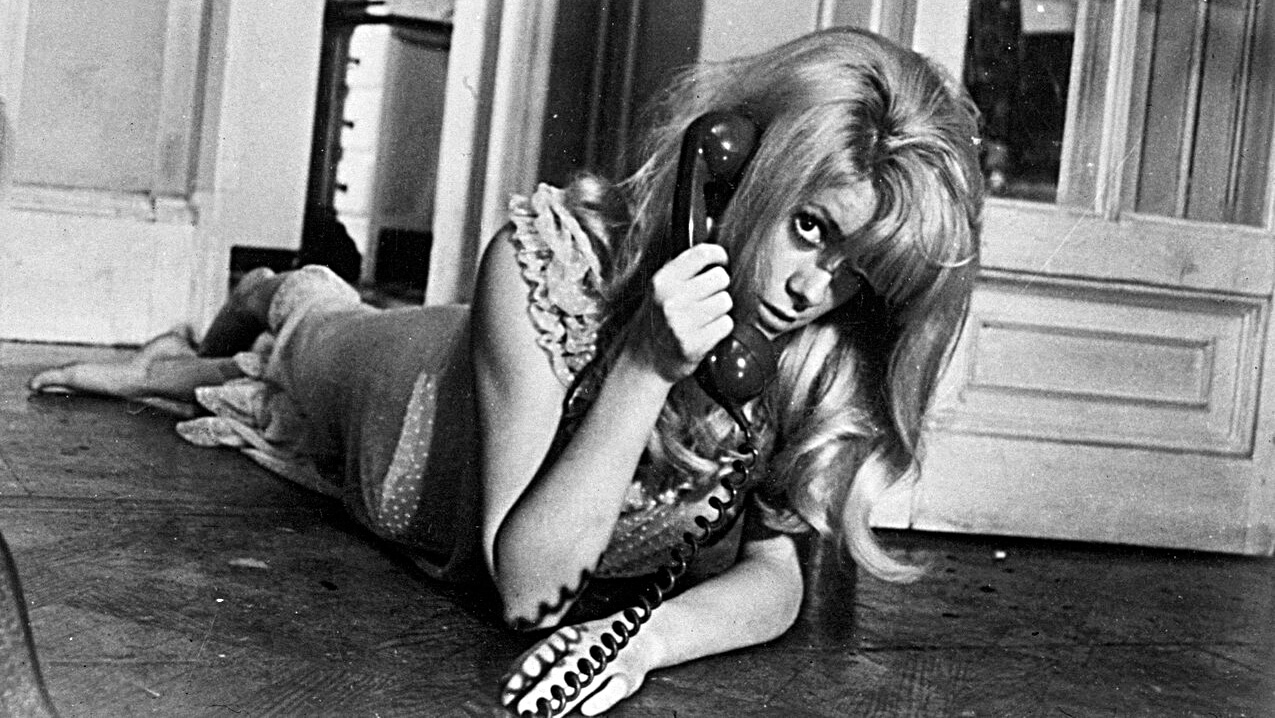

This gap between one’s own experience and the objectively existing reality had to be played by Catherine Deneuve, inexperienced in such a style of acting – cold and psychotic. Only seemingly, this innocent blonde with exceptionally angelic beauty does not fit the role of a mad murderess. Polanski in Repulsion aptly combined traits considered in popular culture as symbols of innocence (youth, long blonde hair, shyness) with the way of perceiving the surroundings characteristic of Norman Bates (Psycho). This combination can even irritate because it is not intuitive. From the beginning, it is clear that something is wrong with the main character, Carol Ledoux. Her long musings, almost suspensions, especially with clients in the beauty salon, cannot be interpreted as mere job dissatisfaction or temporary sadness due to loneliness and problematic relationships with her sister Helen (Yvonne Furneaux) and her lover, the mysterious Michael (Ian Hendry), who is always around their house.

Polanski does not hide the cause of Carol’s state at all. The answer is shown in a long shot already in the seventeenth minute of the film, when the camera stops at a family photo. In the idyllic photograph, you can see several generations and even a dog. Everyone is laughing, except for the long-haired blonde standing in the background. She looks at the man sitting on the right with eyes full of hatred. It is easy to guess that this is her father. It is also easy to link her disgust towards everything male with the relationship shown in the photograph, starting from undershirts, shaving creams, brushes, to dinner in male company. Carol’s father sexually abused her. He taught her to feel disgust and, at the same time, to humbly adore his smell as an irreplaceable part of existence, a prosthesis simulating authentic relationships with people, a macabre union of parental and lover’s roles.

And here Polanski could have faced the difficulty of how to present the process of such sick persistence visually, using very indirect means. And above all, how to suggestively present the process of descending into madness, not in the didactic way of Hitchcock’s Psycho. Bergman liked to go for philosophical conversations and monologues breaking the fourth wall in such situations. For Polanski, the ideal solution turned out to be limiting dialogues in favor of pantomime conveyed to the viewer in long shots, close-ups of the face, and stopping the camera on objects important to the plot (the photo, the decaying rabbit, the razor). And, of course, an open ending. Polanski’s implication does not have to be articulated at every possible occasion. It is enough for the lens to gently suggest where to look. All this, however, would not work if not for the suspense.

In the first half of Repulsion, seemingly nothing happens. Only fragments of unease reach the viewer, especially those expecting a clearly explained action. Time flows at a leisurely, weekend pace, and the main character, Carol Ledoux (Catherine Deneuve), performs the routine tasks of her daily life until boredom and later hatred. Because what has life really given her? A poor job in a beauty salon, where she deals with someone else’s nails, struggles with elderly clients who think another algae mask will save them from old age? Loneliness next to an extroverted sister who loudly has sex behind the wall? But if Carol wanted to change something, she certainly could. Instead, she prefers to lock herself in her malaise, disgust with the perceived world around her, which of itself has given and will give her nothing good. One would have to take it by force, try hard, often hiding one’s true opinion about it. Carol, however, cannot. She is uncompromising, so she must eventually lose. She is still trapped in her childish perception. Is that bad? If she hadn’t murdered Colin, locked herself in the house, or cut a client during a manicure, her madness could surely be considered a kind of extended perception of the environment, while onlookers would see her as a harmless social melancholic. But as it is, she is a classic lunatic with murderous instincts leading to emotional anarchy, which offers no chance for a normal life.

The claustrophobic space of events in Repulsion never brings relief to the viewer. It gets worse and worse. The rabbit rots, flies swarm over it. One corpse bleeds out in the water-filled bathtub, another lies under an overturned couch; after all, it was hard to treat the owner of the apartment (played by Patrick Wymark) any other way in defense against rape. Few people, however, notice one of the last scenes when Helen returns with her lover to the ruined house, and he carries Carol out in his arms. The gathered neighbors can only stare, as if watching a rare specimen of a wild animal carcass in a museum. They are a metaphor for the environment in which Carol lives, gargoyle masks filmed up close, slightly from below, to suggestively distort the perspective – a very common technique today. It is natural, then, Polanski seems to say, that in such a world one can only hide under the bed, and in special situations defend oneself, even through murder. This moral ambiguity in assessing Carol’s actions and state is deepened by Michael’s behavior. He is the only one brave enough to carry her in his arms, the only one who does not turn his gaze away from the corpse in the bathtub, but quite the opposite – besides natural disgust, his face shows a kind of shameful pride, while he looks at the semi-conscious Carol with concern. Perhaps in a twisted way, he envies her because he too wants to let go and be free. Perhaps it’s a director’s sneer, and his arms mean that Carol will never be free from sexually and mentally exploiting men, and Michael has already deemed himself a worthy successor to her perverted father? Or maybe Carol, not her sister, was always more attractive to Michael, and now he finally has her, defenseless, just for himself? Either way, Carol is once again at the mercy of male strength.

It’s hard to piece together this perfectly filmed puzzle by Gilbert Taylor. Polanski in Repulsion provides the code but not the key to deciphering it. Perhaps that is what we call madness. We see the symptoms when it has already progressed too far. The art is to enter someone’s mind and reach the source before someone beheads a rabbit and starts carrying it in a purse. The art is also to leave someone alone and risk that they will manage because the line between otherness and madness can be thin.

Polanski did not show just one aspect of Carol’s life in Repulsion. He consistently presented her whole life, including the vivisected process of descending into catatonic madness. There isn’t much of it because Carol lives frugally. One could assume she is still a virgin, and in her dreams or sick hallucinations, this brutally torments her. On one hand, in her delusions, she is raped; on the other, when hands emerging from the walls grab her breast, she feels aroused. She constantly wants to be close to ugliness and decay, hence the rabbit left out in the open, and later the desire to carry its severed head in her purse. The final stage is barricading herself in the apartment, completely succumbing to fear, and desperately defending herself from the advancing world by murdering Colin, who breaks down the door in his love-struck state. Repulsion

The time when Polanski went to the mythical West came when we already had the skillfully made Knife in the Water. It is maintained in a very similar rhythm to Repulsion, although the open space of the frames creates the impression of faster action. Nothing could be further from the truth. Polanski practiced psychodramatic suspense in Poland, so that in his first foreign film he could burden only one person with it – Carol (Catherine Deneuve), a depressive and psychopathic manicurist. Knife in the Water doesn’t have a dramatic ending. No one dies; only the car standing in the final scene at a deserted crossroads testifies to a deep-seated doubt about any sense, captured as a minimum of concern for the fate of others. It’s only about the primal struggle to survive, but that crossroads is stronger. Having everything, from the perspective of Andrzej and Krystyna (Jolanta Umecka, Leon Niemczyk), you can continue, hiding behind things. But from the perspective of the Boy (Zygmunt Malanowicz), you can’t. He is full of life, ready for crazy action, and sharp like that knife in the water, which for both men is a symbol of everything desired and, with time, lost in the depths of the lake, untempered and therefore weak, but once having the chance to be like rock. The Boy wants to be someone at all costs, wants to be Andrzej. However, he must disappear in confrontation with the hard, practical reality or wait, which he is too impatient to do. And Andrzej? He envies the Boy’s primal freedom, when nothing, no feeling, obligation, or thing stands in the way. Then opposition to the surroundings has the unique taste of madness experienced alone.

These boundaries of existential absurdity were clearly articulated only in Repulsion. Knife in the Water is merely a forerunner of the madness that Polanski will consider in his films many more times and will tangibly experience in his personal life in a few years. Carol also does not want to wait or do anything rational. The reality of objects and feelings for others overwhelms her so much that the only way out seems to be to kill Colin (John Fraser), as if in defiance of the fact that it could be a chance for something new. Carol’s desire for change has long since turned into its opposite. Her disgust with stagnation has provoked an attachment to it, an addiction to feeling unfulfilled. Breaking this vicious circle would mean giving up the exciting feeling of lack, hence the contestation of the world regardless of what it is like, whether it really offers a chance or just torments with the crude advances of a simple worker from the street or shakes with visions of paternal rape.

Looking back destroys because it makes us dependent on the experienced disgust, loneliness, and despair. The rabbit’s eyes are dead unless we look through them, pretending to be another creature. It’s just a symbol, just as events from the past become symbols. In essence, neither the rabbit nor the past mean anything except what we tell ourselves about them, what narrative we assign to them for the rest of time. The rabbit’s eyes are not dead, only if we think so. But will we have the courage to throw its rotting carcass into the trash? Repulsion