PILOT PIRX’S INQUEST. Surprisingly good adaptation of Stanislaw Lem

Is it the sum of our capacities to love, forgive, show loyalty, or curiosity, in other words, the ability to make morally difficult choices, laden with consequences and responsible for our own and our loved ones’ destinies? Is this where the strength lies that makes us feel human? Certainly, many people would sign under this declaration. But is there a situation where the affirmation of humanity would manifest with altogether different factors?

One of the greatest creators of science fiction literature, Stanislaw Lem, presented the realization of such an idea in the story The Trial from the collection Tales of Pirx the Pilot from 1968 turned later into a movie as Pilot Pirx’s Inquest.

Lem’s works, due to their complex moral themes, have always been a thorn in the side of filmmakers, tempted by the practical realization of the spectacular and narrative values of his books. Therefore, the results of transferring the novels and short stories of the brilliant writer to the screen, in his own opinion, were not satisfactory. Already in 1960, in a Polish-East Germany co-production (there was once such a country…), The Silent Star was made by Kurt Maetzig, based on Lem’s The Astronauts. In 1963, our southern neighbors realized Ikaria XB 1, a story about an interstellar expedition. Director Jindrich Polak didn’t even hide that the film was partly a camouflaged adaptation of Lem’s The Magellanic Cloud. Two years later, Marek Nowicki and Jerzy Stawicki made two half-hour television films, The Friend (based on the story of the same title) and Professor Zazul (based on the third story from the cycle From the Memoirs of Ijon Tichy, which in turn is part of the collection The Star Diaries).

In 1969, unexpectedly, Andrzej Wajda, wanting to take a break after the hardships associated with filming Everything for Sale, directed Layer Cake for television (based on the story Does Mr. Jones Exist?). Lem personally wrote the screenplay for this comedy starring Bogumil Kobiela in the lead role of a rally driver whose gradual transplanting of body parts increasingly erodes his own identity. In the 1970s, it was time for Stanislaw Lem’s most outstanding work. Solaris was filmed twice in the Soviet Union. In 1970, Nikolai Nirenburg directed a two-part TV film, and two years later, the great Andrei Tarkovsky presented his version of Kris Kelvin’s struggles with the phantoms generated by the thinking ocean to the world. Finally, in 1974, Marek Piestrak made a television adaptation of Lem’s detective novel, The Investigation. A few years later, the same director attempted to film the best story from the Tales of Pirx the Pilot cycle. Thus, the literary Trial became, in 1979, the film Pilot Pirx’s Inquest.

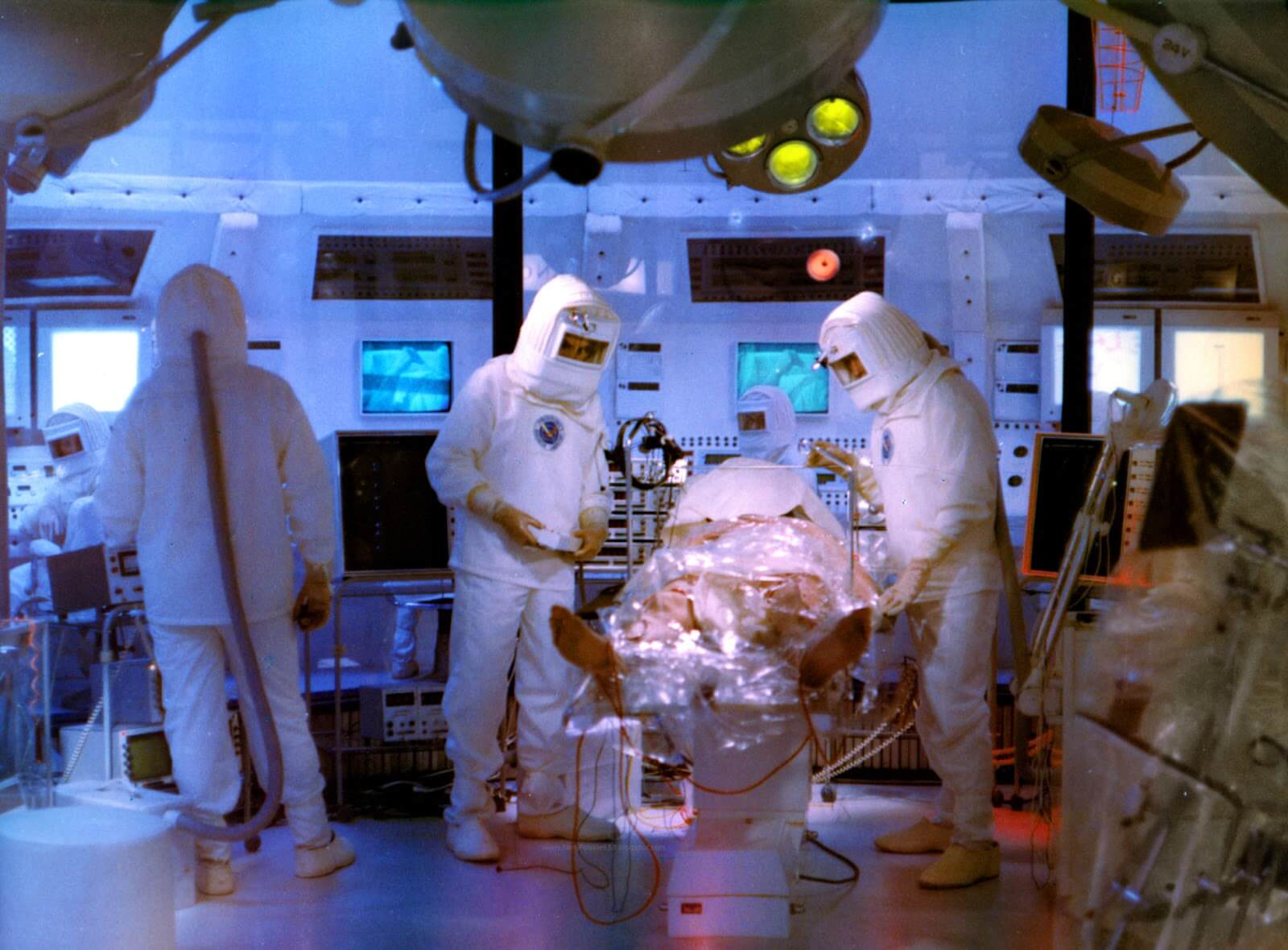

In the Cybertronics laboratory, scientists construct an artificial human (at a decisive moment, even electrical discharges are visible, reminiscent of the film Frankenstein…). At a secret session of the UNESCO committee, a decision is made to entrust Commander Pirx with an extremely important task. Pirx takes on the responsibility of commanding a spacecraft crew, which, sent towards the rings of Saturn, is to place an observation probe in the so-called Cassini Gap, a narrow strip of space between the rings. The mission’s goal is purely pretextual. The commissioning party is only interested in comprehensive testing of the crew, among whom there will also be a model robot, a so-called finite non-linear. The problem is that Pirx cannot know who, or how many, of his subordinates are not human. The flight begins…

WARNING – SPOILERS !!!

After just a few days of travel, the second pilot, Harry Brown, confesses to the commander that… he is human, at the same time casting suspicion about the robotic origin towards the electronics technician, Jan Otis. For the surprised Pirx, this is just the beginning of inquiries, suspicions, and revising the assumptions of his subordinates. Neurologist and cyberneticist Tom Novak goes even further – he tells Pirx that he is a robot, while explaining what prompted him to make this confession, prohibited by the agreement. Another candid crew member of the Goliath is the nuclear engineer Kurt Weber, who, while not revealing his own identity, casts suspicion towards… Brown. Bewildered Pirx, having no basis to trust anyone anymore, begins to believe that all members of the crew may be non-linear, triggering in him an unmistakable aversion to his subordinates. Only the first pilot, John Calder, personally invited to Pirx’s cabin, demonstrates a purely professional approach, without any personal jabs at his colleagues. And simultaneously with Pirx’s investigation, someone manipulates the onboard probe launcher, someone asks the computer to execute a forbidden orbital maneuver, someone sabotages the onboard equipment, and finally, someone hands Pirx a video cassette with a robotic warning…

Finally, the moment of placing the probes in the Cassini Gap arrives. The sabotaged launcher doesn’t work. Pirx is silent. Calder, planning to “lose” the probe at its target, decides to direct Goliath on a suicidal trajectory towards the Gap. Pirx is silent. Acceleration increases. The crew, pinned by G-forces to their seats, can no longer do anything. The ship enters the Cassini Gap. Pirx is silent. And Calder… gets up to pull out the overload fuses. Pirx orders acceleration. Calder, with the remnants of his strength, grabs the control panel with the overload fuses, but the G-forces tear him away from it, leaving only his hands, from which protrude jagged steel and cables… But Pirx is mistaken in thinking that John Calder was the only non-linear among the Goliath crew. Several weeks later, on Earth, during a meeting with the alleged robot Novak, Pirx notices a scar on his hand, which was part of Novak’s robotic story aboard the ship…

END OF SPOILERS

Lem, and after him Marek Piestrak, presented a situation in which the perfection of a robot, its belief in its superiority over the fallible human, was overcome precisely by human sluggishness, human ignorance, doubts, and fear. The precise, cold logic of the non-linear, confronted with humanity, manifesting as a sum of weaknesses, defects, and flaws, suffered defeat. The robot could not hesitate or have a bad day. Pirx, hearing contemptuous judgment of humanity on the video cassette, even though made by the creation itself, decided to fight the non-linear on the plane that the machine did not comprehend. The strength of the human became that which humans usually struggle against within themselves. The director convincingly portrayed this paradox on screen.

The visual aspect, however, was much worse. Marek Piestrak is a director who seems like a man who wants a lot but can do little, and as a result, always falls off the high horse. And sometimes, unfortunately, it glaringly stands out, especially in Pilot Pirx’s Inquest. Budgetary constraints contributed to this, as did the peculiarities of cinematic SF “museum of imagination,” largely manifested in scenic anachronisms resulting from the current state of technology. Simply put, screen gadgets are a futuristic version of the objects surrounding the creators. Even the “wonderful” equipment of the laboratory from the beginning of the film now looks like a depot of ancient oscilloscopes made in the Soviet Union.

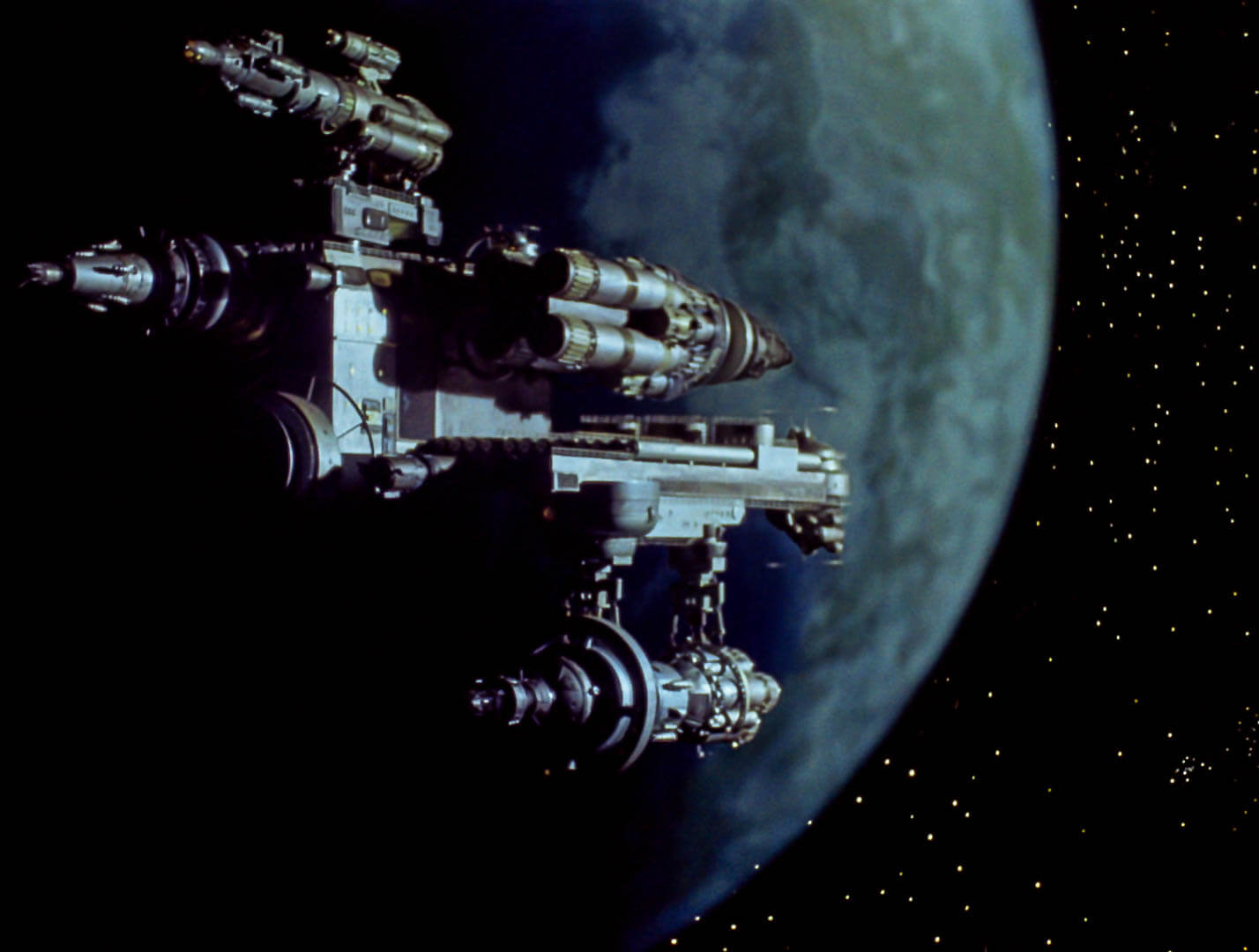

The same goes for the controls of the Goliath. The computer screens at the pilot’s stations look like illuminated boards of pinball machines and arcade games from the 80s. Meanwhile, real screens serve as televisions coupled with cameras. Following 2001: A Space Odyssey, the central computer speaks with a male voice. In homage to the literary source material, Calder commands the computer: “give me the approach area to Saturn according to Stanlem’s celestial navigation.” The most spectacular element of the ship’s scenery is the large window-screen, probably inspired by Star Trek. From this series, the naive patent of moving stars, simulating movement in space, was also borrowed. The thrust levers, resembling railway switch levers, are amusing. The model of the ship in space emits flames from the nozzle like a burner, and the rings of Saturn up close resemble a sponge.

The film also features such attractions as shooting with a disintegrating laser at a swarm of meteorites – after dealing with one, suddenly four more appear, even though they weren’t there before… And with the zeal of a maniac, Marek Piestrak insisted on adding annoying sound effects by Eugeniusz Rudnik to every technological gadget. It’s as if every device had to buzz before it could work. I understand that in this way the director wanted to achieve the so-called “science fiction effect for the mass audience,” meaning the weirder, the better. But years later, this effect is embarrassing.

The Earth sequences are also a catalogue of shortcomings. The futuristic artery, along which the non-linear was transported from the laboratory, is the famous Wrocław “concrete highway,” where advertisements for the late Pan-Am airline were placed (an interesting paradox – socialist cinema showing that in the future only imperialist corporations will remain). The view of New York from an airplane looks to me like a shot stolen from the film Love or Leave, although I wouldn’t swear to it. The problem of showing several New York skyscrapers in the film was solved by the crew’s visit to Paris, where such buildings are not lacking. Unfortunately, the cameraman accidentally captured the streets where, instead of American vehicles, Citroëns, Peugeots, and Renaults were happily driving. Instead, we could admire Pirx’s visit to the exotic for us then McDonald’s. On the other hand, the spectacular scenery of the Moscow airport terminal was probably used on the principle of “since it’s standing, let’s shoot”. Therefore, during the screening, we are treated to the absolutely unnecessary scene of Commander Pirx traveling among conveyor belt-like, glass-covered corridors of the arrivals hall.

Nevertheless, the film is quite watchable. This is largely due to the absolutely serious treatment of the subject matter by the director. We know – cosmic science fiction works best in English, and it’s easy to fall into the trap of unintended hilarity when a local character boasts about being at the helm of his domestically produced spacecraft and then rattles off some technological gibberish in Polish, reserved for the Enterprise crew. But when Zbigniew Lesien, as John Calder, reports to Pirx on the progress of his service, during which he made two landings on Mars and Venus, somehow this bragging is credible. And the whole charade on the Goliath is simply excellent. With dialogues, lighting, and music, Piestrak demonstrated great talent in creating an atmosphere of danger and otherness.

Speaking of music – in the film, we hear two different aspects of it. In the first half of the film, a heavy, symphonic score by contemporary Estonian composer Arvo Pärt dominates, giving way in the space section to unsettling, electronic sounds by Eugeniusz Rudnik. Also noteworthy is Piestrak’s pioneering work. Perhaps for the first time, spacecraft and interplanetary space were shown in a Polish film (or rather Polish-Ukrainian-Estonian). So far, Polish directors had tackled these aspects only twice, and at most in a fairytale context: in Antoni Bohdziewicz’s Galoshes of Happiness (a scene with a UFO) and in Anna Sokolowska’s The Big, Bigger, and Biggest (Groszek and Ika’s visit to an alien planet). The cosmos on screen was the work of Russian special effects experts from the Dovzhenko Film Studios in Kiev. Taking into account the hardware poverty and the lack of experience of our cinematography in mass-producing screen wonders, the effect is at least intriguing.

It’s a pity that Piestrak trivialized and oversimplified the ending of the film. The final statement of the commander regarding the non-linear, which lost because it so contemptuously scorned “human decency,” in the book’s original version made a greater impression, serving as an excellent summary of Pirx’s struggle with the machine. Meanwhile, on the screen, this strong statement is just casually uttered by a resting Pirx. And to top it off, the director serves us a riddle: “how many are there still?” Cinematically, it’s effective, but is it necessary? I doubt it.