NIGHT TRAIN. A hope that someone is waiting at the end of the journey

…, showing its consequences for the entire nation and the psyche of the individual. Almost immediately, Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds is mentioned, along with the other two films in his trilogy (also A Generation and Kanal), as well as the grotesque cinema of Andrzej Munk (Eroica, Bad Luck). Although not all titles revolved around the theme of war, its impact was felt in almost every production.

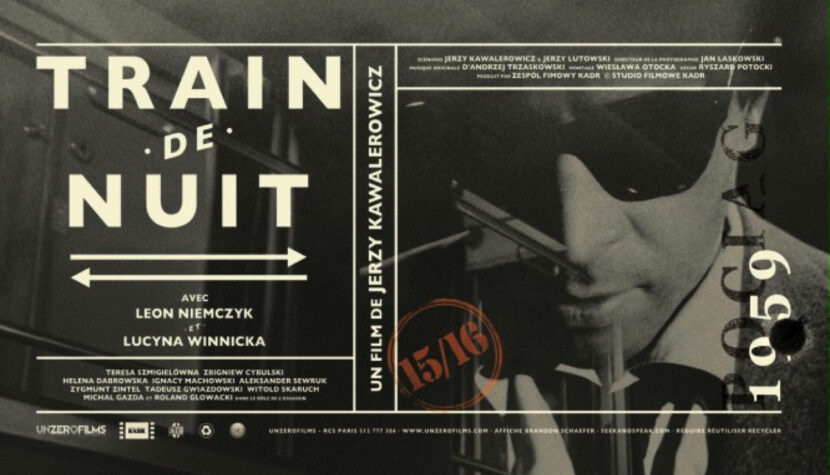

The filmmakers of that era were interested in characters who had experienced trauma, though these experiences began to be defined differently. Poland was a country in perpetual captivity – we traded one oppressor for another, and although the October Thaw gave us the opportunity to speak about certain things openly (though not always directly), complete freedom of speech and thought was still a luxury. Directors increasingly turned away from war memories, noticing dramas in entirely new situations and conditions. Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s Night Train (1959) escapes the reckoning with history and contemporary politics in favor of a story closest in genre to a thriller and melodrama, though avoiding simple categorization.

The film’s action takes place almost entirely on the titular train, on the route from Warsaw to Hel. People populate the various compartments, among them Jerzy (Leon Niemczyk), who is forced to buy a second ticket because he forgot the first one at home. Hearing that the entire compartment is empty, he wants to also buy the adjacent berth, but it has already been taken by Marta (Lucyna Winnicka). The woman refuses to leave, and after an argument with the conductor, the man agrees for them to travel together. They don’t speak much, admitting that they wanted to spend the journey in solitude. However, prompted by a series of events that force them to interact, they begin to grow closer.

Kawalerowicz does not focus solely on these two characters, though he pays them the most attention. He sketches portraits of other passengers, flawlessly giving them depth with just a few words or images. Among them is a lawyer’s wife (Teresa Szmigielówna), clearly interested in forming a close acquaintance with Jerzy; a young man, Staszek (Zbigniew Cybulski, without his iconic dark glasses), desperately trying to find a moment alone with Marta; a former concentration camp prisoner who cannot sleep because the sleeping compartment reminds him too much of that place; a sailor who does not utter a single word but keeps staring at a beautiful young girl who, although embarrassed by the situation, does not stop smiling. Everyone seems to be searching for happiness in their own way.

But there are also men interested in a newspaper note about a murder committed the day before, suspected to have been done by the victim’s husband, who is now on the run. Though this subplot adds some dynamism to the story, suggesting a turn towards genre cinema, the director resists this temptation. Instead of delving into who among the passengers might be responsible for the heinous act, he prefers discussions about the difference between murder and manslaughter and asks the young priest whether confession can secure a criminal’s place in heaven. The criminal situation becomes a pretext to show different ways of perceiving and explaining crime. Until the end, we do not learn the reasons behind the murder. Thus, the act itself is described in a few words in the newspaper, and the passengers’ unfulfilled curiosity finds an outlet when the police board the train.

Jerzy becomes the main suspect, but it’s hard to believe he is the wanted criminal. At no point do we feel threatened by him; he does not create the impression of someone capable of violence. Marta also does not fear him, even though she tells him at one point that he looks at her as if he wanted to kill her. She quickly recognizes in him someone similar to herself – a victim, not an executioner. Both hide their pain behind a mask of aloofness and laconic dialogues, carefully observing the other without expecting anything. Or maybe they do? The woman at one point states that no one loves anymore, but everyone wants to be loved. This thought perhaps best sums up Kawalerowicz’s timeless masterpiece.

Night Train is, above all, a film about the need for connection, not necessarily love, but closeness with another person. This cannot happen without understanding the partner’s needs and a certain harmony of characters. Therefore, the sadness and unfulfillment shared by Jerzy and Marta allow them a moment of truth that would be impossible to find in the arms of those who intrusively impose themselves into their lives. Both the lawyer’s wife and Staszek must fail in their desperate attempts to attract the main characters, as their own needs obscure the true nature of the situation. Both eventually capitulate, helpless in the face of the utter indifference of the other side, although Marta will not lack admirers. The director observes all the passengers with empathy and understanding, without seeking to find fault or punish any of them.

Even the murderer, whose identity we learn, does not appear dangerous but ultimately defenseless. The chase scene in the light of the rising day still impresses with its staging, beautiful cinematography, and above all, the slightly unreal atmosphere of the entire sequence. At the junction of night and morning, the men run out of the train, which the criminal had stopped in the middle of a field to escape. They seem to participate in a hunt – each wanting to capture the murderer first and mete out justice as they see fit. The end of this sequence confirms Kawalerowicz’s intentions, who strips even the criminal story of cheap sensationalism, opting instead for a resignation full of helplessness and compassion. The participants of the chase return to their compartments and continue their journey, remembering the recent events but already thinking about the rest awaiting them at the end of the route.

Amidst other films of the Polish Film School, the subtle Night Train may seem like a less significant work compared to the more famous and representative films of that period. It does not touch on the war and social issues so prominent in the works of Andrzej Wajda and Kazimierz Kutz, nor does it render the screen reality surreal as Wojciech J. Has or Andrzej Munk did. It uses elements of genre cinema but does not conform to the requirements of melodrama or crime fiction.

Unfulfillment becomes not only the film’s theme but also Kawalerowicz’s creative premise, whose existential drama makes us yearn for something unattainable, just like the characters. We convince ourselves that we are happy in our loneliness, like Marta, but an opportunity for closeness awakens hope for true affection. However, it does not come, and we close ourselves off again, distrustful of the world and the other person. In Lucyna Winnicka’s eyes, we see disappointment, resignation, and fatigue, but the director also turns the camera on other passengers, content and full of life, implying that a person is never truly alone. Even if they want to be.

Despite Kawalerowicz avoiding pessimism in the finale, he leaves the viewer in a state of sadness that does not, however, feel depressing. So when I return to this film, I do so for the passengers, their small and larger dramas, the jazz music with the unforgettable vocals of Wanda Warska, and precisely for that overwhelming feeling of sadness and nostalgia. And every time, I hope that at the end of the journey, someone is waiting for Marta.