HOUR OF THE WOLF. Psychological horror by Ingmar Bergman

In mythological tradition, it is the moment of release of destructive forces, preceding the destruction and rebirth of the world. Carrying strong apocalyptic and infernal, pagan connotations, the term served as the title of one of Ingmar Bergman’s most predatory and dark films. Although Hour of the Wolf is relatively rarely mentioned among the Swede’s greatest achievements, it is one of his most original and visionary films, combining his typical psychological and metaphysical tropes with the aesthetics of gothic horror.

Filmed in 1968, the movie was based on an unrealized script abandoned in 1966 in favor of the memorable Persona. Inspired by authentic nightmares and childhood traumas of the creators, Hour of the Wolf tells the story of Johan Borg, a renowned painter living with his pregnant wife Alma on a small Swedish island. Suffering from insomnia, Johan is haunted by disturbing visions of monstrous creatures and his former lover, Veronica Vogler. The delirium of the man somehow connects with the inhabitants of the island’s palace owned by Baron von Merkens, and Alma begins to fear more and more for her husband. Borg’s advancing neurosis increasingly blurs the boundaries between reality and his nightmare fantasies, ultimately leading to extraordinary and tragic events.

In Hour of the Wolf, Bergman employed a characteristic narrative scheme of intermediate storytelling, in which the action we see is a reconstruction of events by Johan’s missing wife. By utilizing this narrative frame, where Alma introduces and comments on the main action, Bergman brackets the fantastic dimension of the plot without weakening its realism. What we see on the screen is the reality of Johan’s visions and paranoia, replayed with sad tenderness by his abandoned wife. In this doubly subjective perspective, the island and its inhabitants undergo a demonic distortion, and the anxiety materializing in von Merkens’ sinister mansion permeates their summer idyll. Tormented by visions bordering between waking and dreaming, deceived by cultural refinement and reminiscent of past aristocratic passions, Borg consistently heads towards compulsive self-destruction by succumbing to the dark forces surrounding him in his sense of isolation. The horror here is based on the fusion of erotic desire and a drive towards death – breaking Johan’s mental integrity, which opens the way to directly depicting dreadful visions.

Sexuality in Hour of the Wolf shines with a turpistic glow of pervasively enticing, subconscious desire for self-destruction. The intertwining of horror and perversion in Bergman’s film creates a surrealist aberration of reality, surpassing the boundaries of realism and sinking into dark phantasmagoria. The initial psychological tension and misanthropy of Borg gradually give way to terrifying visions. Two women play a crucial role in Johan’s dynamics – the loving and tender Alma and the debauched, erotically charged Veronica Vogler. They embody opposing ideals, between which the male hero is torn – the gentle caregiver of the hearth and the ambivalent, unrestrained lover. The domains of both women are visualized topographically by the idyllic summer space and the gothic mansion and dark marshes. At the core of the film is the sexual-emotional tension in the triangle of Alma–Johan–Veronica, representing the paradoxical feelings of the protagonist, whose life seems barren and whose death is seductively illuminated by disturbing eroticism, also indicating his distancing from the tangible towards illusion and fantasy.

The essential concept of Hour of the Wolf is encapsulated in Johan’s completed sentence uttered by Alma: “It’s in this hour that the nightmares come to us… and if we don’t sleep, we’re afraid.” It is a vision of the deepest, most stirring nightmares tormenting the soul of a sensitive artist. The subtly manipulating light and shadow by Sven Nykvist become an emanation of fundamental fear and disorientation, revealing the dark lining of existence. Bergman creates a surrealist experience of the main character, suspended between life stability and fulfillment (symbolized by the summer house where Borg lives with his sympathetic, loving wife) and a demonic space of erotic temptations, elite decadence, and instincts of destruction (manifested in the castle). Thus, the filmic expression of the subjective experience of the titular “hour of the wolf,” a cruel nightmare, serves as a starting point for a nuanced psychological portrait of the main character and the woman trying to save him.

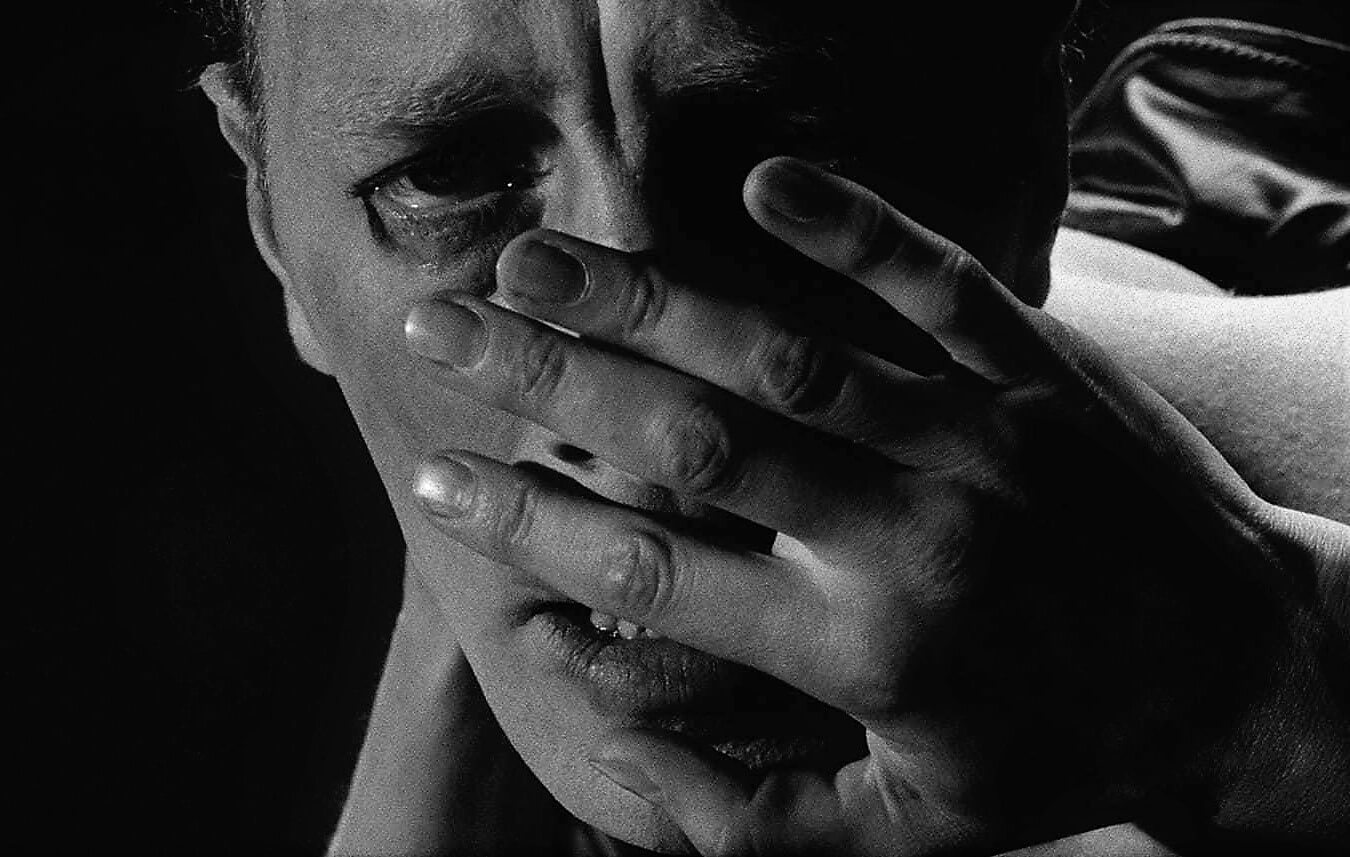

This vision would be incomplete without the outstanding performances of Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann. In one of his most outstanding roles, von Sydow embodies the neurotic tension of his character, perfectly conveying with his restrained but expressive emotional expression the stretched emotions of Borg between the material world and the reality of nightmares and erotic desires. His stony face vividly illustrates alienation from his loving wife and family peace, while his desperately widened eyes express all the ambivalence of fascination with the demonic charm of demons and apparitions. Equally important, in the final analysis, is Liv Ullmann – in her typical, nervous way visualizing Alma’s despair, trying to understand her husband and protect him from his own death instinct. This duet, counterpointed by exaggerated, demonic roles of Ingrid Thulin (as Veronica), Erland Josephson, Gertrud Fridh, Georg Rydeberg, Ulf Johansson, and Gudrun Brost (as inhabitants of the palace), gives Hour of the Wolf a realistic tragedy that resonates perfectly with its incredible, horrific setting.

In the past, Bergman often reached for a turpistic, pessimistic aesthetic, but never before or after did he create a film as organically suffused with horror as Hour of the Wolf. The suggestive, almost gothic visual layer generates an incredible, fascinating, and terrifying atmosphere in the 1968 film, corresponding to the tragic struggles of a character lost in the abyss of spectral dreams, internal demons, and a sense of existential emptiness. Formally, Hour of the Wolf is a full-fledged horror – subordinate to Bergman’s poetics and themes but still horror. The Swedish master achieved a truly virtuosic harmony between his characteristic psychologism and introverted metaphysics and Strindbergian imagery of anxiety and decline.

Hour of the Wolf emerged in perhaps the most intriguing and refined phase of Ingmar Bergman’s career. After creating a clear, authorial language of cinematic metaphysics and artistic fulfillment in films like The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, or Persona in the 1960s, the Swede began to create openly intimate films. Incredibly aware of cinematic form, Bergman brilliantly utilized his combination of severity and poetics, creating ambiguous, interpretively evasive film visions, oscillating between the creator’s inner phobias and sophisticated reflections on philosophical and psychological matters. Particularly noteworthy in Hour of the Wolf is how the violent exteriorization gains strength through the transgression of man struggling with inner demons. Due to its aggressively plastic convention, it may be the most direct – albeit openly fantastic – film by Bergman.

Hour of the Wolf is another indirectly autobiographical statement from Bergman about the sense of disintegration and loss in life, a sense of impasse and loneliness of the world-renowned artist who feels that no one really listens to him. Bergman thus creates his own alter ego, realizing self-destructive tendencies, projecting onto Liv Ullmann (his then-partner) the figure of a caring mother, a compassionate caregiver who transforms into a tragic character unable to help her beloved. The trajectory of presenting Alma is perhaps the best (even better than those used in films focused on female characters) illustration of Bergman’s approach to femininity – simultaneously demanding, essentially patriarchal in expecting unconditional love and subordination, and deeply empathetic and proto-feminist in building reflective portraits of trapped, seeking autonomous exits from existential traps of heroines.

For Bergman, The Hour of the Wolf could be a form of self-therapy during his private “hour of the wolf.” Paraphrasing folk motifs and intertwining them with Mozartian phantasms from The Magic Flute, he creates a fascinating dramaturgy of conflict between reason and instincts, reflecting the fundamental themes of his work – struggles with childhood trauma, sexuality, and a sense of alienation and loneliness. As a result of filtering inspiration through the director’s individual perspective, a visionary, thoroughly authorial psychological horror film was created, which to this day continues to intrigue and frighten with its cruel subtexts.

Bergman experimented with cinematic form in a brilliant way, perhaps most radically in his career, pushing the aesthetic visualizations of his authorial obsessions. The result is a unique, refined film that is also an incredibly complex example of blurring genre boundaries and a polyphonic dialogue of modernist cinema with cultural tradition. The ambiguity and depth of Hour of the Wolf are perhaps best punctuated by the words of Johan Borg himself: “The mirror has been shattered – but what is reflected in its shards?”