KNIGHTS OF THE TEUTONIC ORDER. Polish blockbuster for the ages

Scholars might criticize its simple plot, naivety, and lack of sophistication. Andrzej Wajda might have despised it, believing it distracted from the more valuable achievements of the Polish Film School. Nevertheless, Knights of the Teutonic Order from 1960 remains a spectacular production. To not see this, one would have to be a bored fourteen-year-old watching it the day before a test.

Ignoring the elements that have clearly aged, such as costumes seemingly taken from a school play, Knights of the Teutonic Order still withstands the test of time. It transports viewers to another era, as the atmospheric songs, shots of wild animals, and the beautiful back velar “ł” spoken by the actors enhance the magical impression of interacting with a long-gone world. Kazimierz Serocki’s beautiful soundtrack, reminiscent of 15th-century scores, completes the atmosphere.

The most famous segment of the film is, of course, the battle sequence: a 15-minute segment constructed from 152 short, dynamic shots. Today, it may not impress as much as it once did; the chaotic charge of Polish knights is no charge of Rohan, but the build-up to the fight is an example of masterful tension building. It is foreshadowed from the very beginning with a sneak peek of two naked swords, suggesting that the entire plot will lead to this great event. The two pre-battle speeches by King Władysław Jagiełło and Ulrich von Jungingen, shown in parallel montage, effectively highlight the differences between the “good” Poles and Lithuanians and the “bad” Teutonic Knights. And then there are those two naked swords with which the German knights diss the Poles hiding in the forest. And Bogurodzica sung by Polish knights, which always gives me chills. However, my favorite fight scene is the duel between Zbyszko and Rotgier. That moment when the camera moves “behind the visor” of Rotgier, who realizes his companion is dead and thus he too will soon die, is chilling and moving. It is also one of those rare moments in Knights of the Teutonic Order where Ford rises above Sienkiewicz’s partisan narrative and the anti-German propaganda of the communist Poland, recognizing the humanity on the other side.

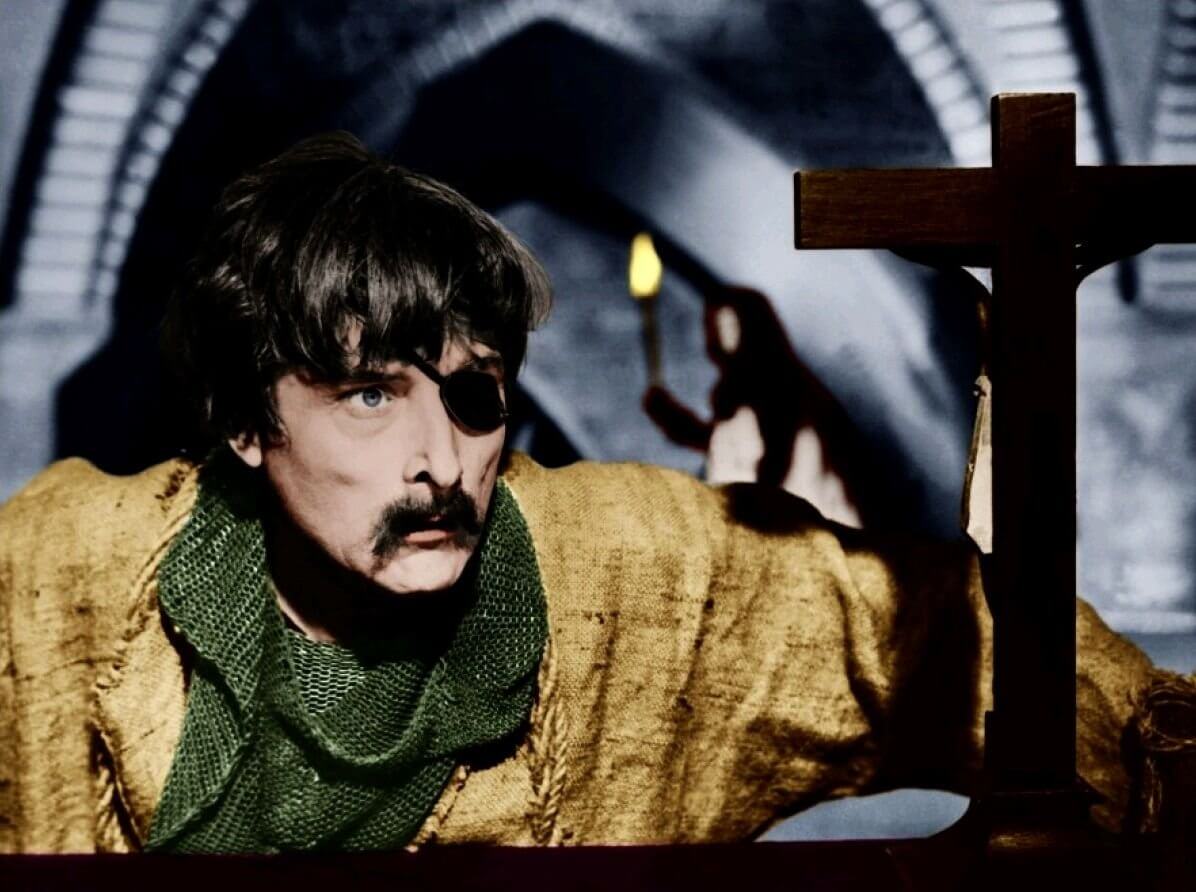

This is not just a story about men. Women also drive the events. Urszula Modrzyńska as Jagienka is the embodiment of charm, and I truly do not understand how one can watch her performance and not fall in love with this lively, sincere, and roguish girl. A wonderful, passionate acting performance. But I equally like the other, less distinct character, often dismissed contemptuously as a “bland mimosa.” Subtle, sensitive, artistic Danusia, played by Grażyna Staniszewska, may not fit our times, but she evokes tenderness in me. Despite her shyness, she saves her chosen one from death by shouting “he is mine” in one of the most iconic scenes. She also breaks our hearts when she dies shortly after being rescued from the Teutonic Knights’ hands—exhausted, terrified, insane, and most likely after numerous rapes. The scriptwriters, Aleksander Ford and Jerzy Stefan Stawiński, wisely decided to devote a large portion of the film to the subplot of Jurand of Spychow. His search for Danusia, humiliation, and mutilation is the most dramatic part of the book. In the film, it is equally moving, thanks to the appropriate amount of time allocated to it, and Andrzej Szalawski’s charismatic portrayal of Jurand.

How did it all come about?

Of all Sienkiewicz’s bestsellers, Knights of the Teutonic Order best fit the rhetoric of the communist Poland era. Władysław Gomułka’s politics were clearly anti-German, and the 550th anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald was approaching—so it is no surprise that the authorities spared no expense for the first Polish superproduction. The film’s budget is estimated at 33 million złoty, a staggering amount at the time, putting Knights of the Teutonic Order on par with Hollywood hits. Selecting Aleksander Ford as the director was not accidental. He was entrusted with Knights of the Teutonic Order as a form of rehabilitation after his adaptation of Marek Hłasko’s The Eighth Day of the Week was shelved. Ford himself wanted to regain the authorities’ favor and once again become Poland’s most important director, a position taken from him by Andrzej Wajda.

It was to be the first Polish film shot on panoramic tape and the second in color. The monumental historical fresco entailed equally monumental work and costs. Without the support of the communist authorities, such a film would have been impossible to make in the conditions of the then Polish cinematography. The best color tape, Eastman Color, was used for the filming, not the previously used Agfa from East Germany. Panoramic lenses were used for the first time in Polish history, the real army was engaged for battle scenes, nearly 30,000 costumes were sewn, and the final recording was sent to Paris for laboratory processing. In this advanced technology, there was also room for artistry: cinematographer Mieczysław Jahoda was inspired by Gothic art and colors. The grand set design was created by Zdzisław Kielanowski, Roman Mann, and Tadeusz Wybulta.

In those times, stuntmen were not used on film sets, so there were numerous accidents during filming. For example, Mieczysław Kalenik, who played Zbyszko, was mauled by a bear. Other problems were caused by extras who could not resist eating the appetizing food from the tables during feast scenes. It took the threat of docking their pay to stop the gluttons, but the food problem did not end there. When it came time to shoot scenes where the extras could finally eat, the meats had spoiled from standing too long under the lights. Forced to eat spoiled food, the extras revolted and refused to work: the meat had to be cooked again. For the next feast scene, the crew came up with a better solution—artificial food was placed on the tables. Only Emil Karewicz, playing the king, got a real chicken: actually, several chickens, as there were many takes. The other actors, hungry after many hours of shooting, looked at him jealously. Finally, one of the Teutonic knights begged: “You, Jagiełło, be a man, throw at least a wing!”.

All these efforts were wrapped up within about a year: after all, they had to meet the deadline, and no one wanted to upset comrade Gomułka. The first, ceremonial screening of the film took place on July 15, 1960, the anniversary of the battle, as part of the Millennium of the Polish State celebrations. The film went into general cinematic distribution on September 2, 1960. In Polish screening rooms in large cities, villages, and towns, Knights of the Teutonic Order was seen by nearly 33 million delighted viewers. I imagine it must have been three hours of absolute magic, a brief escape from the harsh reality of communism into a simpler world. This attendance record was built up over years, but it does not diminish the achievement. It should be remembered that distribution used to be much slower than today, premieres reached smaller towns with a delay, films were shown longer and more frequently repeated. Knights of the Teutonic Order was also sold to 45 other countries.

Was I biased in this article? Of course. I love this film. Knights of the Teutonic Order is my childhood, and like everything from the old days, I look at them through the eyes of nostalgia.