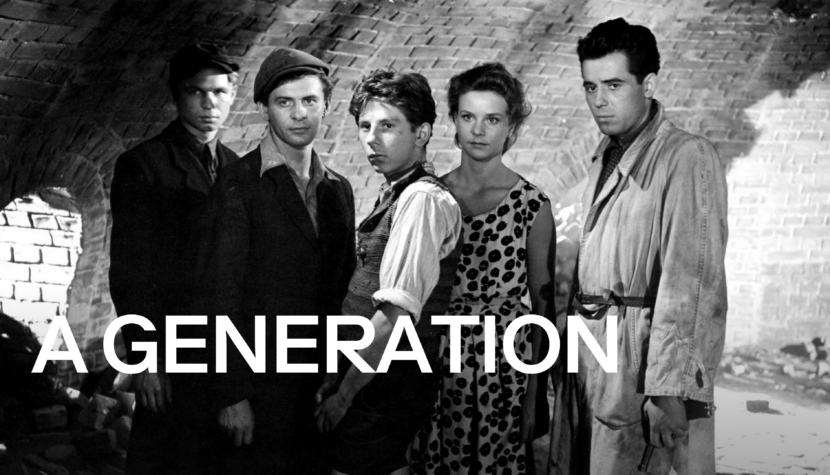

A GENERATION. Andrzej Wajda’s Controversial Debut

…or even that post-war Poland did not exist at all. It undoubtedly did exist, and valuable creators lived there, who did not necessarily have to act against the people’s regime to create beautiful and valuable things. Moreover, they could support and honor it while still being great artists.

In this context, the young Andrzej Wajda debuted ambivalently and controversially, but most importantly, in line with the party’s line. A Generation is a tribute to the People’s Guard – could this statement only be made by today’s right-wingers or nationalists, who are allergic to all manifestations of leftism? Or is this moral opposition of the People’s Guard to the Home Army and the National Armed Forces simply a historical ideologization, normal for changing political interests and the passage of time? Perhaps Wajda indeed made a film about people whose ethical decisions cannot be verified without the Nazis behind them and the hundreds of thousands of presumed saviors from the Red Army ahead of them?

First, let us clarify something clearly and rationally, as it is reflected in the plot of A Generation. Regardless of one’s ideological stance, if judged solely on the merits, Wajda’s debut is not only a praise of the People’s Guard but also of communism in general. I am well aware that both right-wingers and capitalists sometimes suffer from something like a “red fever” against rational facts, which most often manifests itself in equating leftism with socialism and communism. In the case of A Generation, regardless of what one believes, if one wants to be objective, it must be stated that this film is steeped in red color and praise for the oppressed working class. This is not accidental, meaning the entire core of the plot is based on the idea of socialist distribution of the means of production and is not just a necessary compromise in a few plot points to push the film through censorship to distribution. Maybe during Stalinism, no discussions were possible? Fortunately, the red color of the film neither diminishes the tragedy of the characters nor devalues the question I posed at the beginning: in those times, times of the collapse of all ethics, could young people decide which organization would be best to fight the enemy, and who, besides the Nazis, was also an enemy at that time?

They could not, as clearly shown in the scene where Stach (Tadeusz Łomnicki) and Sekuła (Janusz Paluszkiewicz) talk. Wouldn’t such an argument presented by a much older and more experienced person resonate with a young, poor, and uneducated boy looking for his place in the wartime reality? Sekuła mercilessly listed only the facts. He practically illustrated the owner’s profits from the carpenter’s shop and their relation to Stach’s daily wage. He presented the real situation of the owners of the means of production even during the war. The war would end someday. Even if the Germans won, the worker’s situation would not change because, as a certain bearded man (Marx) once wisely said, “A worker is paid only enough to regenerate their strength for the next day’s work. Nothing more.” This was done by the Nazis, capitalists, nationalists, monarchists, that is, all those who wanted to maintain the class structure of society.

Abstracting from the communist overtone of the arguments, it is hard to deny their logic. Now, during the war, the old MASTERS either fled or were exterminated by the occupiers. Only those who were so far considered trash, an oppressed mass to increase the wealth of the higher-born, remained. Those who call themselves YOU remained. So, how could they not want to take something for themselves under occupation, especially since the idea of destroying the intelligentsia in the Polish nation by the Germans was, in some inhuman sense, very favorable to them. The emergence of the communist People’s Guard in such an environment turned out to be paradoxically quite natural because a thoroughly ideological war was happening around. The idea of racial purity confronted the class reconquest.

In both these cases, the group that felt strong and valuable enough wanted to subordinate its own or conquered state. Communist ideologists knew perfectly well that the war period was the best time to sow social unrest. They also realized that in the history of earthly societies and their conquests, it has never yet been possible for invaders to completely annihilate the intellectual elite. It always regenerated, if not from the noble or bourgeois root, then, ironically, from the so-called peasants. Therefore, working on the living tissue of a war-degraded nation gave the greatest chances to implant the idea of socialist freedom in the young, who would bear their children in a completely different, communist-subjugated reality. However, the communists did not realize that achieving a state of full equality is impossible because, just before that, an elite would first form within the communist community and then both its rebellion and the grey nation’s opposition to its actions would occur. Thus, communism will transform into an authoritarian state form by itself, striving from within towards a revolution, similar to the one that happened in bourgeois society and led to the birth of communism.

So how to break free from this redundant circle of uprising? Wajda did not give an answer because he could not. After all, he made the film during the period of Polish Stalinism. Maybe he believed in what he was doing, or maybe he calculated like a clever young man. Maybe he also deliberately hired Tadeusz Łomnicki for the main role, who first belonged to the Home Army and then, for several decades, to the Polish United Workers’ Party. What a contradiction. According to Wajda, the People’s Guard are true saviors compared to other organizations like the Home Army or the National Armed Forces, which is clearly evident when Master Ziarno (Zygmunt Zintel) and a richly dressed man, describing himself as a member of the Underground Army (presumably the Home Army), come to look for Stach in his house. They behave like bandits. They are haughty, determined, and aggressive. They are only stopped by the opposition of the neighbors called to help Stach. In this scene, Wajda unequivocally presents the differences between the people and the two speculators. The people are ragged, dirty, and smelly, but united. Mr. Ziarno and his guest look like businessmen capable of anything. They have money, which in times when people are dying of hunger is unthinkable. However, the truth is not as black and white as Wajda presented it. There were plenty of businessmen and degenerates in the Home Army, but the People’s Guard was no less anti-Semitic and humanly vile, not to mention what happened in the ranks of the National Armed Forces. And in the film A Generation, some are simply bad, while others are exclusively good, almost like in an American superhero movie. In politics and war stories, such morally simplistic tales rarely happen, though let’s not lament too much over their moral naivety, since our contemporary national right-wing uses similarly simplified narratives to speak to the people almost like Sekuła to the young and eager-to-fight Stach.

Red as a brick, Wajda chisels our capitalist skull with the one-dimensional character of Stach like a powerful dose of psychotropic drugs numbing the senselessness of the world. However, in the background, there is someone who overshadows Łomnicki with his ambiguity – Tadeusz Janczar as Jasio Krone. In him, the director hid all his rebellion against the system, unnoticed by the monolithic censorship. Jasio didn’t need ideology to fight. He didn’t have to kill Nazis under any specific banner. It was enough that he felt Polish. At first, he didn’t want to get close to the People’s Guard cell because he cared about his old father. Later, he realized that he wouldn’t sit out the war, hiding from confrontation and pretending to work peacefully. In his situation, the simplest thing was to join the group formed by Stach, regardless of whom its members served. The magnificent Tadeusz Janczar in the role of Jaśko proves that there is no need to ideologize the fight. One can fight for oneself, to save oneself, and still rise much higher than any red, black, green, pink, or whatever other banners.

As Kazimierz Kutz wrote many years later in his autobiography There Will Be Scandal, Tadeusz Janczar was not only one of the most interesting characters in the film due to his acting personality, but special effects were also experimented on him. Condoms filled with paint were used for this. This was invented by the assistant director, who was Kutz himself. Small explosive charges burst the latex along with the fake blood, which for the first time in Polish cinema realistically depicted multiple hits from a machine gun. Kutz did not speak as warmly about Wajda. His greatest complaints were especially about Wajda’s way of working. He accused him of laziness, lack of ideas, and relying on other people. Wajda himself did not have the film in mind, he did not see it, so others shot his productions, and he only came to judge if such a vision suited him.

Maybe Wajda wasn’t so red after all, but only pretended to be someone else out of necessity? Maybe, as Kutz accused, he pretended to be a director throughout his life, cleverly relying on the skills of others. I leave the answer to these questions to the viewers, unequivocally still stating that A Generation is a propaganda film of an exceptionally scarlet color. Nonetheless, it is a surprisingly modern film stylistically, excellently shot aesthetically, and artistically refined. The noir atmosphere mixes with psychological drama and war film. These three genre components coexist, creating a great, albeit propaganda, cinema of a young creator who intends to say much more to both the authorities and the audience.

It may seem that Wajda’s approach to the search for identity among the young had to involve ideological belonging of some kind, as long as it had some ladder of concretely named principles. Jasio didn’t have them – he was a civilian, a “bare” human, yet he was capable of going to his death. For all ideologies, he was like a traitor, a sore, a punch in the face for loyalty to authorities. As it turns out, Wajda in A Generation is not just red like the titular brick. He is a flesh-and-blood cunning anarchist because sometimes you have to go with a certain wave to find your own and ultimately go against the current, return to the source where there is nothing but untamed humanity. We come into this world with nothing. We leave it with a similar burden. Ideologies, values, and beliefs are unnecessary add-ons for which we senselessly die, unless like Jasio Krone, we fight for something essential to our existence – freedom broader than a few square meters of our sleeping space.

It is necessary to adopt colors because sometimes we have to deceive the world to protect our own still fragile identity, but it also means that we can never lie to ourselves.