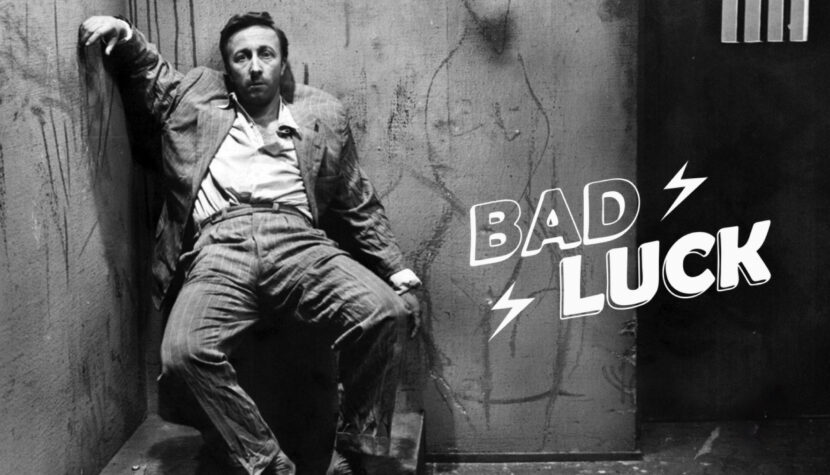

BAD LUCK. Hilarious, but a Masterpiece Nonetheless

The adventures of Jan Piszczyk are usually treated as a comedy of errors, mistakes, and the satirical acrobatics of a fool and a naive person seeking solace in superficial values.

However, the fate of the hapless protagonist is not merely an ordinary farce meant to entertain audiences looking for relaxation, fun, and a break from the real world. Munk is rightly called a creator of the Polish Film School, which had much to say about history, politics, and humanity. Bad luck

MUNK vs. WAJDA

Together with Andrzej Wajda, Munk initiated a new trend in Polish cinema, a kind of reckoning with both the past and the present – pre-war Poland, Nazi occupation, and the birth of the Communist People’s Republic of Poland. Boldly engaging in a dialogue with history, Wajda’s and Munk’s temperaments revived collective memory and refreshed the stagnant poetics of Polish film in the first decade after the war. The years 1939-1945 were the most profound experiences for both directors, prompting the then thirty-something creators to revisit Poland’s recent history, especially since post-war cinematography nearly ignored wartime and occupation themes. When they did tackle these topics (like The Last Stage about the Auschwitz camp or Border Street about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising), they often sidestepped Polish issues, particularly those requiring an accounting. Audaciously, Andrzej Munk presented his Man on the Tracks in 1957, while Andrzej Wajda reminisced in 1955 with A Generation. They slightly irritated still fresh wounds and agitated the political class: audacious and magnificent!

However, the two creators differ significantly, possessing different sensitivities, viewing their characters differently, and imposing different forms on their films. Wajda loves metaphors, lyrical tones, romantic and heroic inspirations; when Maciek dies in Ashes and Diamonds, it is a heroic death, a defeat after fierce battle, a tragedy of mythological proportions. The same applies to A Generation, Kanal, and other reckoning works by Wajda, filled with romanticism rooted in national tradition and insurgent history.

Munk is different. He stays closer to contemporary times and employs the language of documentary film, which is simple, loose, often ironic, and satirical, though ideologically serious. We won’t find grand stylistic metaphors or romantic lyricism and tragedy in his films. We won’t encounter internally torn heroes suffering on screen. Munk doesn’t detach from reality, nor does he use metaphorical language to tell his cinematic stories. Why present meanings when they can simply be suggested? Munk’s camera observes human fate authentically, reflecting the complexity of reality created by the forces controlling it without resorting to clear symbolism. Interpretation is left to the viewer, who sees the world somewhat “pure,” unencumbered by patriotic, historical, and literary values, as well as romantic tradition. The world through Munk’s camera is unique, having no counterpart in post-war Poland – its fabric is reality, and if allegory sneaks in, it’s more in the spirit of Chaplin than Italian neorealism or Buñuel, whose representatives were Wajda, Kawalerowicz, or Has.

With this extended introduction, I intended to present the figure of Andrzej Munk, who passed away half a century ago, now somewhat forgotten, especially since the throne of the King of Polish cinema is eternally held by the Oscar-winning Andrzej Wajda – a paragon of all film virtues, as is commonly believed. Besides, there is nothing about him – yet – on this website, so the above text shall serve as a modest introduction to the work of this outstanding director.

But let’s return to Bad Luck, which I personally consider the most daring and best film by Andrzej Munk. Some prefer to elevate the earlier Eroica from a year before, while many regard Passenger from 1962 as Munk’s crowning achievement. It’s hard to deny that Munk’s oeuvre consists of only excellent works, but the embodiments of Jan Piszczyk fully showcase the genius, originality, and bravery of the young creator. He created not only a pleasant comedy with a funny protagonist but also brilliantly examined, through Piszczyk’s persona, the history of the Polish nation. Munk rejected romantic heroism and placed the man with bad luck center stage. Piszczyk performs as much as the audience allows him, rejoicing when they applaud and fleeing when they boo.

THE CAREER OF A LOSER

Bad Luck is the story of the great unlucky man Jan Piszczyk, who, out of sheer vanity and immediate benefits, continually dons new uniforms. He is an opportunist, far from heroic attitudes, though he wishes to be seen as a hero. Unfortunately, someone always trips him up, someone punishes him for naive conformity, something always bothers and hinders him.

He cannot please his tailor father, as he is a klutz and an innocent fool. In school, his classmates torment him, the teacher gets angry, the boy gazes dreamily out the window and sees scouts marching on the field in tight formation, to the rhythm of the troop leader’s whistle. Piszczyk rushes to the field, gets a trumpet, and starts playing – the troop leader is full of admiration, and the other scouts also applaud the young talent. The parade approaches, for which the boy diligently prepares by playing the trumpet everywhere, even in the toilet. Soon we see Jan proudly marching before an officer, an insurgent from 1863, and the statues of Chopin and Sobieski. A mischievous friend puts sneezing powder into Piszczyk’s trumpet, causing him, the whole troop, the leader, the officer, and the insurgent to sneeze. The boy is expelled from the scout ranks, and thus ends the dizzying career of the little loser.

The first few minutes of Bad Luck outline the entire future path of the unlucky man. Piszczyk will always assume the roles of other people, adopting attitudes characteristic of the times. Wanting to escape mediocrity, he strives to join the elite, and when he succeeds, he must shine, he must succeed in the eyes of others. He joins a student organization that organizes a pre-war demonstration against Lithuania. In a series of humorous scenes, we see Piszczyk carrying a banner saying To Kaunas, while students chant Leader, lead us, Long live Śmigły-Rydz. Suddenly, opponents appear – oppositionists from the national camp shouting contrary slogans, such as Down with Sanation, Jews to Madagascar. At that moment, Piszczyk feels, as he says, the power of the collective, but when he sees the political opponents dangerously approaching, he shouts enthusiastically and fearfully: Leader lead us! Jews to Madagascar! Long live Śmigły-Rydz! Down with Sanation! Soon the Jewish shops are being demolished, and in the general chaos, Piszczyk runs away. He bumps into a distraught Jewish woman, wants to comfort her, but the police arrive and beat the poor student.

PAINTED SOLDIER

In this scene, Piszczyk is both pro-government and anti-government; he is a philosemite and an antisemite. He is naive, fearful, foolish, but also good-hearted. Munk does not ridicule the hero but throws him into the whirlwind of events, allowing us to observe typical attitudes dominating Polish society. The background becomes clearer as we move to the next stage of Piszczyk’s “career” – this time, the unlucky man goes to war. The hero is enchanted by the allure of the uniform and the gaze of women following soldiers. He decides to join the cadet school, but in September 1939, war breaks out, complicating his plans. Like every Pole at that time, Piszczyk wants to be a soldier, but unfortunately, the barracks are destroyed, and the country is in chaos and disarray. Our hero finds a cadet uniform and, at that moment arrested by the Germans, pretends to be someone he is not. He continues his story in the POW camp for officers because, as he says, he did not have the courage to admit the truth. Besides, everyone admires him, treats him like a valiant man who fled the battlefield from the planes shredding his unit like cabbage. Unfortunately, the truth comes out, and the Polish officers take Piszczyk for a German spy. Again, bad luck befalls our hero, this time because the uniform fit too well, even though it wasn’t his. Thus ends his military “career.”

Piszczyk then ends up in a German armaments factory, and later, complaining about poor health, returns to occupied Warsaw. The wartime sequences, both camp and occupation scenes, while not devoid of comedic tones, convey the dramatic atmosphere of the period. Humorous scenes continue, but their background: ruins, Nazis on the streets, roundups – are hard to ignore. Piszczyk is terrified, but meeting an old acquaintance, Jelonek, he hopes for a new “career.” He succeeds, becoming an assistant in the business ventures of a Warsaw trickster. Not only that, but Piszczyk wants to appear better than he is. He returns to his camp deceit, once again telling tales of the cabbage-shredding planes and adding a story of a daring solo escape from the camp.

Piszczyk meets his “great love,” Basia, in whose eyes he grows to at least heroic proportions. And in this area, he fails once again – Piszczyk starts playing at conspiracy, resulting in an outcome opposite to what he intended. Not only does the Blue Police accuse him of plotting and distributing illegal prints, but the protagonist also finds himself among a conspiratorial group, where he is unmasked by one of his recent fellow camp inmates. Once again, he is a snitch, once again he loses what he had, or rather what he pretended to have. He was almost happy, he had already resolved that he had enough of pretending, enough of false roles.

THE PEOPLE’S HERO

The war ends, and another “career” of Piszczyk begins, this time against the backdrop of post-war Poland. Our unfortunate hero ends up in Krakow, where he becomes a clerk in the private business of a contemporary swindler. His happy time is brutally interrupted by a raid from the Security Office, which discovers Piszczyk’s substantial savings. His bad luck, immense as it is, intensifies even more in the next sequence, in another “career,” this time in the bureaucratic machinery of the people’s state. Piszczyk turns out to be an ordinary bureaucrat, diligently following orders from “above.” He gets promoted, so once again, he is better than others. The trouble is that bad luck is bad luck, represented here by other brisk bureaucrats similar to Piszczyk, who also aspire to be rewarded and distinguished. And once again, Piszczyk loses, once again his crossed luck torments him. In a fit of despair, he grabs the rifle of an old guard, wants to shoot himself, wants to shoot everyone, but unfortunately, he fails, the bullet – of course, as bad luck would have it – hits the wall.

And what does Piszczyk think of this? In prison, in the sequence that is both the end and the beginning, neatly framing the story, Piszczyk asks not to be released from his cell. Because, after all, who needs such luck? Such crossed luck?

SPECIAL REVISION

Life battered Piszczyk because he was a naive man, slightly foolish, simple-hearted. He was an opportunist faking himself, and we don’t like opportunists because they contradict our notions of bravery, courage, and high ideals. Opportunists fall into superstitions, vanity, and excessive comfort. How can we like Piszczyk when he often faces troubles of his own making; he falls into predicaments that are almost punishments for his sins. This is beautiful and didactic, but Munk’s film is not that simple. The director created an anti-romantic myth about Poland and Poles. He told the story of a country that naturally gave birth to opportunism, that vanity, fakery, illusory struggle, and dangerous compromise, which Piszczyk became a part of. This is very bold, as it disrupts the established historical order where every Pole is the Ever-Victorious Unyielding Warrior of the Polish Nation. There were many such people, but not all followed the path of Maciek from Ashes and Diamonds—there was the cunning Jelonek (or Dzidziuś from Eroica) or the unlucky Piszczyk. Many wanted to wear the uniform because it looked good. Many valued money or love over a rifle, family over a bunker. Many wanted to go to war without knowing why. Crossed luck is closer to life, grotesque indeed, but more real than the metaphorical and symbol-laden wartime reality of Andrzej Wajda’s cinema and similar filmmakers. Piszczyk is an unfortunate soul, but his fate reflects the fate of Poles—and although this interpretation may be controversial, it is worth remembering.

It is also worth remembering Andrzej Munk, as there is currently no one among directors who can deliver the unpleasant and necessary nudge to Polish history. It’s a pity, though it makes Bad Luck all the more of a masterpiece over time.