THE DOUBLE: A Thriller Deciphered; Dostoevsky by Ayoade

… – after the vampire and werewolf – that is nearly universal across all civilizations and cultures, simultaneously sharing a partial identity with the “self”? What’s more, the supernatural doubling, the ominous doppelgänger, is the oldest and most widespread myth of humanity.

Our fear of the doppelgänger is confirmed by anthropology and art, including the most universal modern art form – cinema. There are hundreds of films about doppelgängers. The motif of the doppelgänger can be found not only in German cinema (The Student of Prague), Austrian (Goodnight Mommy), Belgian (The Double, Left Bank), Irish (Wake Wood), American (Double Identity, City of the Dead), but also in Spanish (Darkness), Mexican (Here Comes the Devil), and even Polish cinema (The Double Life of Véronique, Time of Darkness).

The doppelgänger is a very ambiguous entity.

The etymology of this term in different languages points to this. For example the Polish term sobowtór means a repeated being, secondary to oneself, an identical, indistinguishable copy. The German der Doppelgänger translates to “the double walker,” a rich and multifaceted term encompassing all manifestations of duality and meaning: a physical double, a person bearing the same name and surname or the same birth date, a spiritual twin, an immaterial specter, a kind of shadow walking in the footsteps of the living. The literal translation of the French term le double is the double, duplicate, but also specter. Interestingly – le double is also a concept from film theory. Specter relates to the tenth muse and the relationship between image and viewer. Cinema was born as a result of technological discoveries and the human need to create the most faithful reflection – the doppelgänger – of reality (you can find more on this in Edgar Morin’s book The Cinema, or The Imaginary Man).

Since ancient times, the doppelgänger has appeared in the folklore of different cultures and has grown with symbolic meanings. Encountering one’s doppelgänger is a bad omen, a prediction of life tragedy, or even death. The doppelgänger has pejorative and sinister connotations in Germanic, Scandinavian, and Irish folklore. Belief in demonic doubles foretelling misfortune was held by both Goethe and Lincoln. Freud closely studied them, interpreting doppelgängers appearing in dreams and literature. In some cultural circles, the fear of doppelgängers was, and still is, so strong that newborn twins are sometimes abandoned in the mountains or desert. Their fate is to die because a doubled existence is considered contrary to the laws of nature and can bring a curse upon the entire community.

The Romantic period marked the beginning of heightened interest in the rich metaphor of doubling. The significance of this era in popularizing the doppelgänger motif cannot be overstated. Cinema also began its journey with the doppelgänger through adaptations of classic gothic horror stories and novels of the Romantic period.

Films – and other cultural texts – about doppelgängers are stories about trauma, existential crisis, psychological intricacies of the mind, depersonalization, madness, the alter ego, Manichaeism, the opposing forces of good and evil, the duality of human nature, and morality. They are also allegories of internal struggle and, finally, the search for answers to ontological and metaphysical questions about existence, identity, and individuality. Humanity continues to ponder what/who a doppelgänger is.

However, not all films with the doppelgänger motif strike high – often philosophical – notes. This motif is frequently exploited by genre cinema. There are dozens of horror films that draw from the doppelgänger theme.

At the beginning of 1846, Fyodor Dostoevsky, after much struggle, completed his second novel titled The Double: A Petersburg Poem. The chaotic, almost schizophrenic work – which, however, contains a deeper idea and reveals the abyss of the human psyche – was not appreciated at the time but later inspired filmmakers.

The artistic experiment and literary confession of Dostoevsky was taken up by Richard Ayoade, among others. He created a surprisingly successful, coherent, and suspenseful adaptation of this seemingly untranslatable literary work into film language. Ayoade’s The Double, on one hand, only loosely refers to Dostoevsky’s prose; on the other, it is strongly rooted in its themes, content, and mood. It draws from the doppelgänger story structure while contributing something new. Known primarily as a comedian – which adds intrigue – the English director achieved what Bertolucci failed to do years ago with his 1968 film Partner, which was poorly received by critics and audiences alike due to its hermetic and incomprehensible nature.

The opening scene of the film in the subway shows who the main character, Simon (Jesse Eisenberg), is. And he is no one.

When he is rudely asked to leave the seat he’s sitting in (despite the train being empty), slightly bewildered but too insecure to protest, he meekly accepts his fate, stands up, and leaves. Only later will he realize that this was about giving up something far more than just his seat.

Simon. In his case, terms like “loser” or “unfortunate” are euphemisms. He constantly suffers life’s blows. His existence is a parody of life. Meaningless work, visits to his ill mother, sleep, and so on in a loop. An unfulfilled, lonely, and helpless young man, afraid of being labeled “an inefficient relic.” Wearing an oversized suit, with the eyes of a frightened animal, he looks truly pitiful. The only signs of extravagance and courage he can muster are sabotaging the copy machine at work to catch a glimpse of Hannah (Mia Wasikowska) under the neon light of the photocopier.

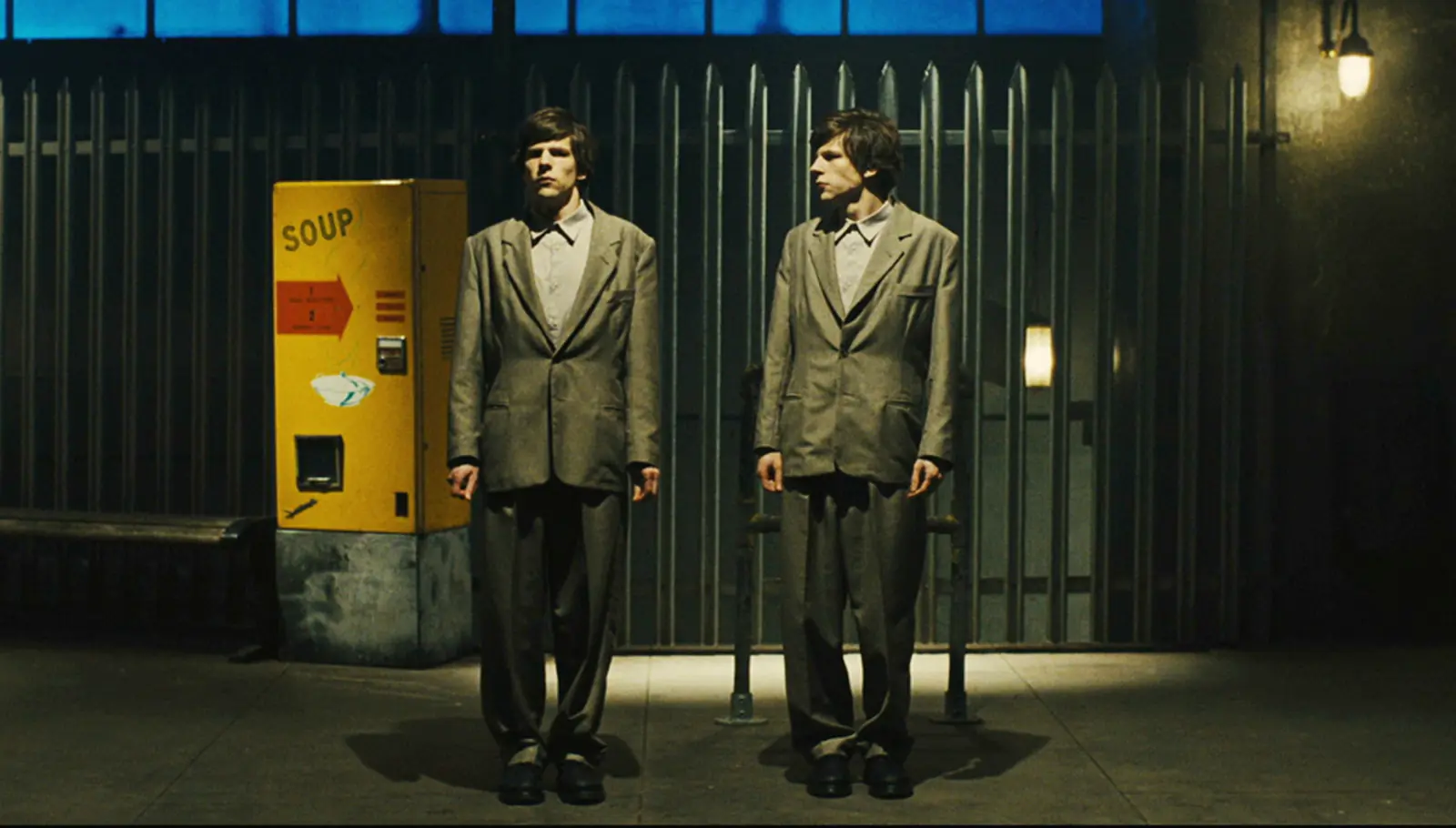

The total opposite of Simon is James, who suddenly appears from nowhere (the characters share the same personal details, but for the viewer’s clarity, Ayoade altered the order, resulting in Simon James and James Simon). The environment seems oblivious to the doppelgänger-like resemblance between the two men. Desperate attempts by Simon to make his colleagues aware of this mysterious phenomenon are dismissed with, “No offense, but you’re unnoticeable.” Even the doppelgänger himself ignores the “original” for a long time. How can they be identical and yet so different? Why is Simon condemned to alienation and loneliness, while his doppelgänger, from the moment he appears in the office, quickly wins everyone over? Despite logic, the two men become “friends.” For Simon, it’s genuine care and attachment; after all, the doppelgänger is his only close person besides his demented mother in a care facility. For James, it’s manipulation, deceit, and feeding on Simon’s naivety. It takes Simon quite some time to realize that James is his antagonist. The rivalry for Hannah’s affection and the struggle for a job promotion reach a new, openly ruthless level. There’s a saying that if you meet your doppelgänger, you must kill him; otherwise, he will kill you. All doppelgänger stories end with the death of one or both…

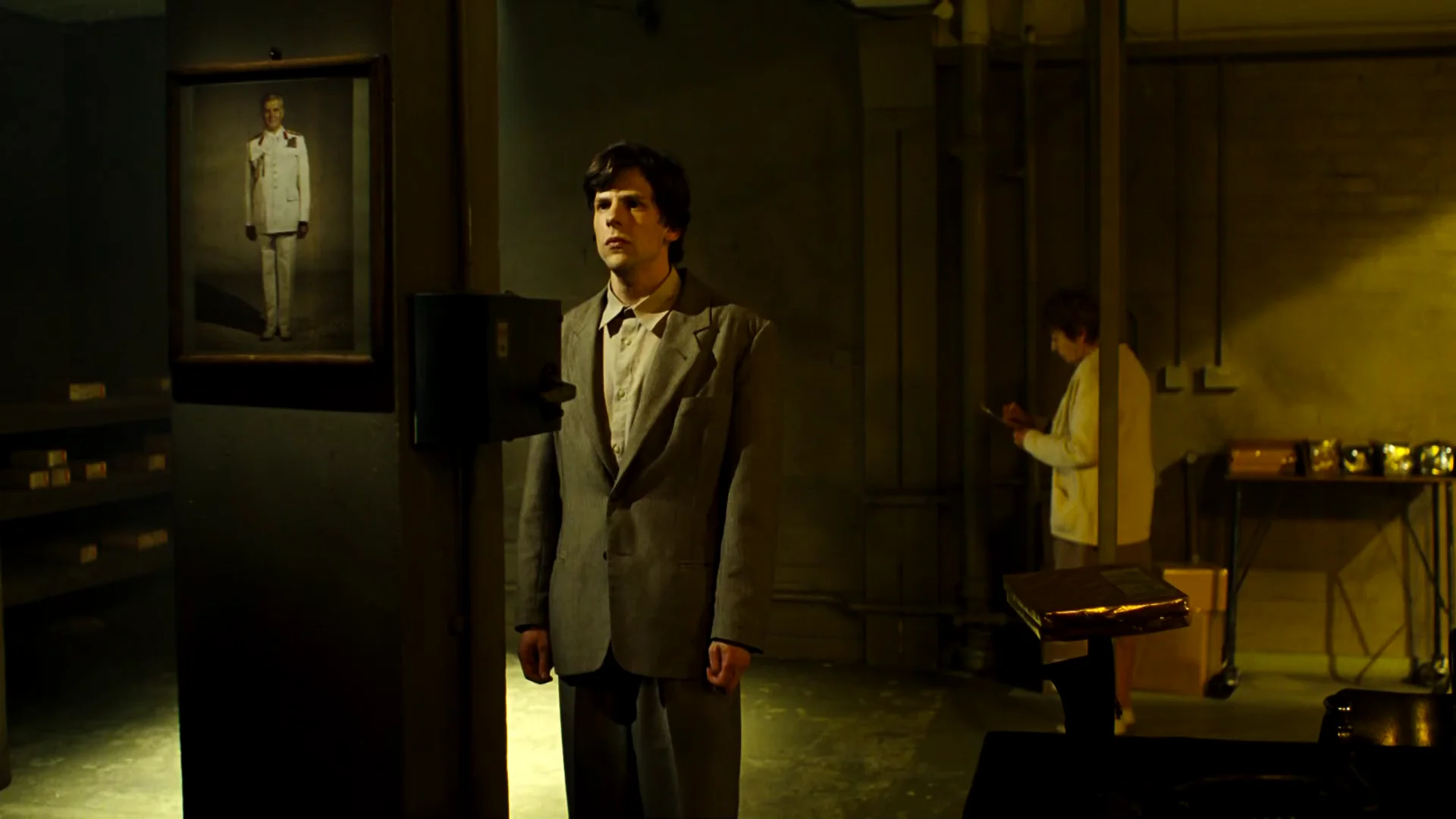

Ayoade’s film features a Kafkaesque-Orwellian atmosphere.

Most of the film’s characters work for a “company” or “office,” but no one knows what – and why – they’re doing there. The protagonist is, for a time, merely rejected and isolated, but then, as a result of a bureaucratic “error,” he’s forcibly pushed out of society. Simon’s evaporation is as absurd as it is final and irreversible. How do you prove you exist when everyone around you claims otherwise? If you can’t be found in the system – even if you’re standing right here, shouting “I am” – you don’t exist. As for Orwellian inspiration from 1984 and its film adaptation, in The Double, we also encounter a society fed propaganda-motivational films, and there’s even something resembling a Big Brother figure. Behind the abstract concepts of “company” and “system” lies the enigmatic Colonel. Everything is done under his command and watchful eye. Rigid norms and zero tolerance for their violation, even if they are absurd and unattainable. The world of The Double is one where even kicking a metal elevator wall can get you fired. The slightest sign of independent thinking, individuality, or resistance is immediately suppressed. Ayoade’s protagonist is a mixture of Joseph K., Winston Smith, and Golyadkin all in one.

In “The Double,” we find more inspirations from the world of literature, film, and art. Ayoade clearly references The Tenant from 1976. He borrowed the scene where Trelkovsky sees his double in the window opposite, the voyeuristic motif with the telescope, and the double suicidal jump from the window from Polanski’s film. This isn’t the only instance where the English director draws inspiration. The Double also includes a direct reference to the paintings of René Magritte. Hannah sketches her self-portrait, which is a variation on one of the surrealist’s most famous paintings, bearing a title that is highly symbolic and meaningful for The Double: Not to Be Reproduced. It’s very likely that Ayoade modeled the physical aspect of the character Simon (Simons) on the image of the mysterious man from Magritte’s painting.

Ayoade’s The Double seems like a modernized version of Dostoevsky’s novel.

The retro-futuristic set design not only creates a unique atmosphere but also makes it difficult to pinpoint the film’s story in time and space. This works in the film’s favor, adding a sense of universality.

Most scenes take place in claustrophobic spaces (a shabby bar, a care home, small apartments) and in the labyrinth of an office (probably underground, as there are no windows, although, upon reflection, it seems that the entire film’s action takes place after dark). Black, gray, and sepia dominate. Only Hannah, both literally and symbolically, brings a bit of color into this dark world. There’s also a stark contrast with the tacky, pulpy superhero TV series, which echoes Simon’s dreams of being “someone.”

It’s hard to put into words how remarkable Jesse Eisenberg’s performance is. He’s neither the first nor the last actor to play a dual role in a single film, but he’s undoubtedly one of those who did it masterfully. Until The Double, his greatest acting showcase was his role as Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network. After watching Ayoade’s film, you’ll surely start associating the actor’s name with a role other than the creator of Facebook.

There’s yet another unforgettable element in The Double: the music. The haunting compositions by Andrew Hewitt, inspired by Schubert’s Der Doppelgänger, convey uncertainty, despair, desperation, dread, and a sense of something inevitably approaching. Without exaggeration, Hewitt’s music is responsible for half of the film’s tension.

Today, we know that Dostoevsky conducted a psychological-literary analysis of split consciousness – his narrative aligns with later discoveries of human mind researchers – but what did Ayoade do? He blended the psychological perspective with a probabilistic one. I don’t think his intention was to depict a split consciousness. Depersonalization, a faltering sense of reality – yes, but for reasons that aren’t as obvious as they seem. The director himself emphasized in interviews that what fascinated him in the Russian classic’s novel, and what he tried to highlight in the film, is the idea that a person can be so invisible and insignificant that no one notices their doubling. The figure trying to usurp Simon James’s life is more than just a figment of imagination. Everyone would like to believe they are unique, but Ayoade denies such a possibility. He managed to disorient the viewer to such an extent that they might miss the fact that the receptionist at the office and the doctor in the hospital are also identical. And – you can trust me – these aren’t the only doubles in the film. Could the director be suggesting that what happened to Simon could happen to anyone…?

Although the creators cleverly balance horror, pathos, absurdity, and comedy, this isn’t an easy film, nor one that will appeal to everyone. The cinematic The Double has depth. I watched it twice, and I’m sure I haven’t discovered everything Ayoade wanted to convey to the audience. I also feel that one could write quite a thick book about the Englishman’s work. But that’s not my field, and I’ve already gone on at length.