THE DOUBLE LIFE OF VERONIQUE. Kieslowski’s Magical Realism

A decade later, in The Double Life of Veronique, the director explored the opposite scenario, depicting the almost identical lives of two strikingly similar women who do not know each other but intuitively sense each other’s existence.

I have a strange feeling. I feel like I’m not alone. That I’m not alone in the world, says the young Polish woman Weronika. The awareness of a kindred spirit has accompanied her for years, but it remains in the realm of intuition and guesswork. Her suspicions are confirmed when she accidentally encounters her doppelgänger. She observes her “twin” from a distance but has no doubt about the striking resemblance. Stunned, she stands and stares at the Frenchwoman Véronique, who, engrossed in taking photographs, does not notice Weronika but unknowingly captures her image in a photo. The Double Life of Veronique

Weronika and Véronique (both roles played by the French actress Irène Jacob) are like one person, duplicated and placed in two different locations. Both lost their mothers in early childhood and were raised by single fathers. Both love to sing. Both have styes on their eyelids, which they try to remove by rubbing a gold ring on them. Their bodies look like mirror images, their life stories—up to a point—also mirror each other. But the mysterious thread that connects them is suddenly severed. Weronika dies.

In their mirrored existences, a rupture occurs. Weronika is dead; from this point on, there is only Véronique, who feels an irrational sadness and depression. She knows she has lost someone important, but she does not know who. Influenced by this loss and unsettling premonitions, she decides to reassess her life plans. It seems that only after the departure of her unknown double does she become a separate person, beginning to make autonomous decisions that are often incomprehensible to others.

Weronika left her beloved without regret to pursue a singing career. She had high self-esteem, focusing on herself and her aspirations. After her death, Véronique, for unknown reasons, abandons her musical passion. She is content with a modest job as a music teacher. She finds joy in meeting people. Her ambition is to find happiness and love. Véronique has a rich spiritual life. She exists in a world of transcendent premonitions, revelations, and a kind of mysticism. This has nothing to do with any religion; the transcendence here concerns only interpersonal relationships.

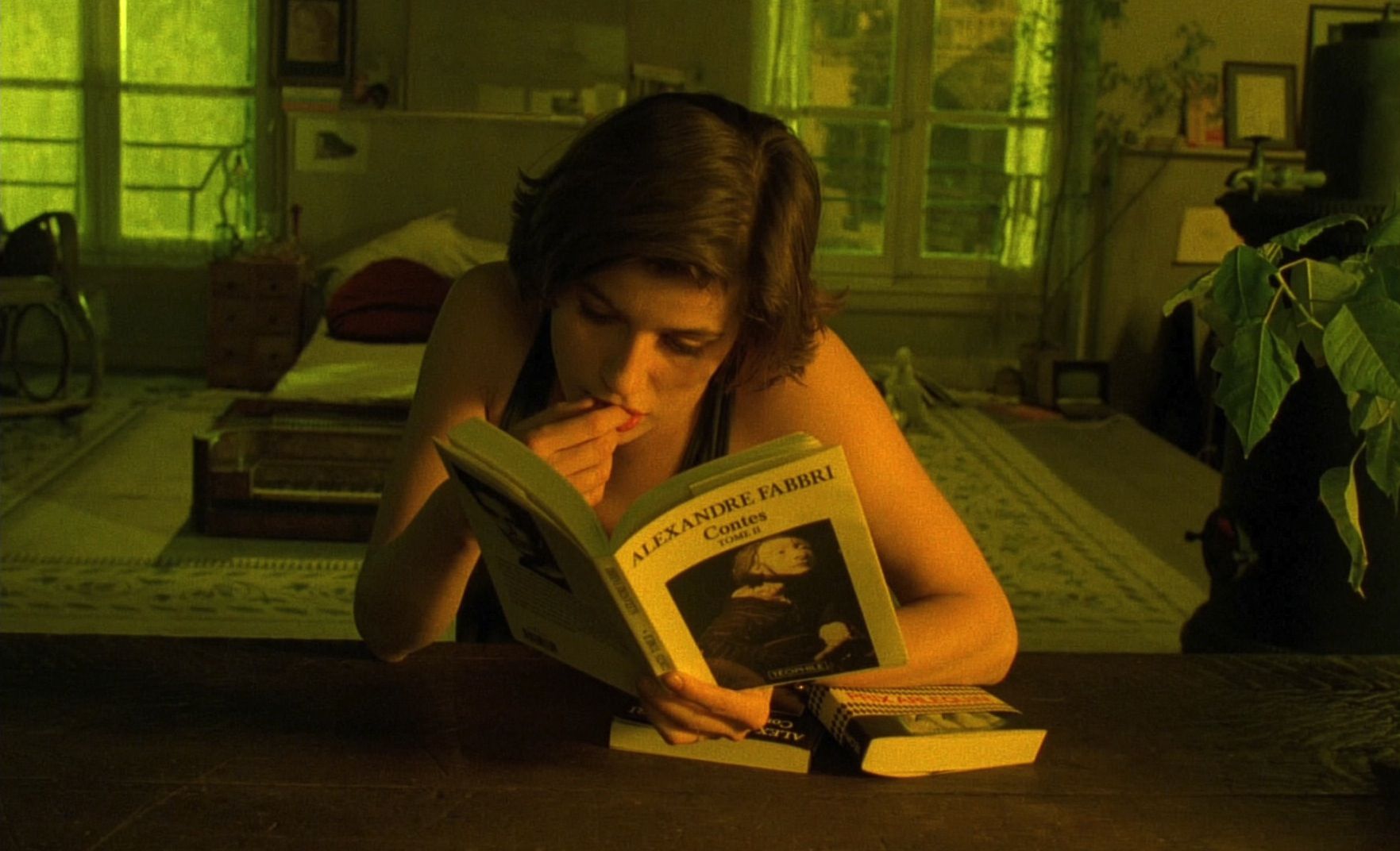

Kieślowski‘s film resembles a fairy tale or a dream. The story on the screen seems unreal—the director used a golden-yellow filter, making the images appear slightly blurred, warmer, and softer than they are in reality. But the fairy-tale character of the film is influenced not only by its form but also by its content, the presence of mysterious objects, symbolism, and the puppet theater motif, which is a transposition of the main characters’ fate. The Double Life of Veronique is cinematic magical realism.

During a visit to her father, Véronique asks if he remembers the image of a Gothic church. It was probably a dream. I saw a drawing. Very simple, almost childish. A steep street in a small town, houses on both sides. And in the background, a church. A tall, spired church made of red brick, she describes. Dream, vision, extrasensory experience, the effect of a supernatural bond, or perhaps a vague memory from another life? This church stands in Weronika’s hometown. The girl looks at it nostalgically from the train window, setting off on a journey to Krakow, and the picture described by the Frenchwoman hangs in Weronika’s father’s apartment. We see it at the beginning of the film when the girl wakes up from a nightmare…

The similarity of experiences of the two young women can hardly be coincidental. Maybe it’s destiny?

Antek riding a motorcycle behind Weronika and Alexandre following Véronique in a van; the hunched old woman struggling with heavy bags, whom Weronika wants to help as a neighborly favor, and the identical old woman whom Véronique watches from the school window where she works; identical glass balls that Weronika and Véronique play with, lost in thoughts and dreams… There are more such seemingly insignificant details, which are signs of the twin fates and mirrored surroundings of the young women—the English title can be translated as both “double” and “doppelgänger” life.

Interestingly, the duality in The Double Life of Veronique also manifests on a formal level. Besides the clearly outlined compositional duality of the film into Polish and French parts, there is also the matter of two different endings. This is a subtle difference—a single additional scene appears in the finale of the version intended for the American market (more on this in Krzysztof Kieślowski’s autobiography published by Znak).

In Kieślowski’s cinematic narrative of The Double Life of Veronique, there is nothing of the dark symbolism of the doppelgänger and the horror of meeting one’s double. Instead, one can see a similarity to a certain literary story that similarly references the doppelgänger motif in an unusual way. Although the director does not directly indicate inspiration from the works of Julio Cortázar, his autobiography reveals that he was familiar with the Argentine author’s writing. In the novel Hopscotch, there is a fascinating idea that two parallel realities exist, which intersect and complement each other. A person can function on these two planes. The characters in the book—Oliveira and Traveler—seem to be one person up to a point; their biographies are so similar, almost identical. They are not physical doppelgängers—although one calls the other his doppelgänger—but there is a characteristic bond and complementary relationship between them, typical of the doppelgänger motif.

This relationship also exists in some way between Weronika and Véronique. They are similar and different at the same time, forming a unity of opposites, complementing each other. At the end of The Double Life of Veronique, we also hear Véronique say to Alexandre: “I always felt like I was living in two different places.” In Hopscotch, we find similar words that could be spoken in the film if the heroines of The Double Life of Veronique had the chance to meet and talk face-to-face: It wouldn’t surprise me at all if you and I turned out to be one and the same person—only each on their own side.