POSSESSION. A Doppelgänger-Flavoured Horror Masterpiece

And it’s not just because of the presence of a mirror in the title. As often happens with doppelgängers, it’s about something that seems like an analogy, yet is also its complete opposite…

The Black Mirror episode titled Be Right Back provides a good context for my very subjective interpretation of probably the most famous film by the recently deceased director. It tells the story of losing a loved one, the death of a spouse, and a grief and longing so immense that the only salvation seems to be summoning a copy of the beloved person, their duplicate. But one cannot create a 100% identical replica of a human being. Stories of bringing back a longed-for deceased show that nothing—neither technological advancements, medical and scientific progress, nor even occultism and a turn to dark forces—can guarantee the return of a departed person. Such stories also prove that what returns both is and is not the person it claims to be. It may have an identical appearance, but a different—evil and dark, or empty—interior. Possession

This duplicate is usually very dangerous. In the best-case scenario, as in Be Right Back, it is a poor substitute. Not similar enough, artificial. It is a false creation. One cannot bestow the same feelings upon it as on the one it tries to impersonate clumsily. But the copy can also be a “better” version of the original. This is precisely what we see in Possession.

Possession is a film about the disintegration of the marriage between Anna (Isabelle Adjani) and Mark (Sam Neill).

Secrets, lies, betrayals, and above all, hellish quarrels. From the beginning of the film, the viewer witnesses not only embarrassing arguments and physical altercations in public places but also the frenzy that ensues whenever they try to communicate. We see breakups and reunions, a semblance of love and a sea of hatred, a lack of acceptance, and self-destructive impulses. Into this horridly real family drama gradually creep elements of macabre, grotesque, and horror.

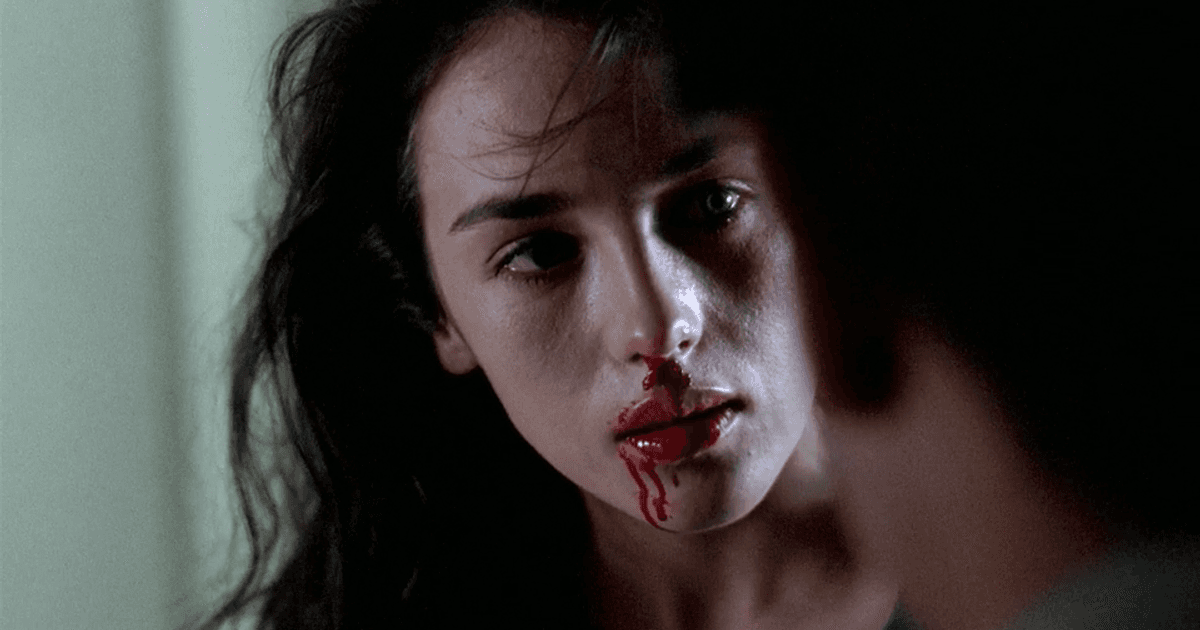

The exaggerated, theatrical acting and a kind of over-expression characteristic of Żuławski‘s films perhaps never found as powerful an expression as in Possession. And this is not a criticism; on the contrary. The film—mainly due to Isabelle Adjani’s brilliant performance, awarded the Palme d’Or and the César for Best Actress—is very evocative, frenetic, and indecently realistic. Even when a disgusting, slimy monster appears in this world, the viewer does not question its reality. It’s not a dream or a hallucination. It really is there.

But where is the doppelgänger, you ask? It is there. Or rather, they are there. The first is the teacher of the main characters’ young son—Helen, Anna’s doppelgänger. The women are not perfect copies; they have different hairstyles, eye colors, and completely different dressing styles, but otherwise, they are the same. Identical face, the same full lips, the same look. But that’s where the similarities end because Helen is not a reflection of Anna; she is her better version. Metaphorically, one could say she is the good twin. Less temperamental than the neurotic Anna, more affectionate, caring, and responsible. While Anna leaves her only child without a second thought, the teacher, upon discovering that the boy has been locked in the house alone for several days, takes care of him with maternal warmth. Mark, although devastated by his wife’s departure and ready to forgive all her infidelities, sometimes recognizes Helen’s “superiority.” Ultimately, however, he chooses the bad sister.

If we are talking about sisters, halfway through the film, the audience witnesses Anna’s insane monologue. Even after four viewings, it’s hard to fully understand it. She talks about two sisters—Faith and Chance. They can live together inside someone, they can accidentally meet on the street… Anna says she miscarried—she uses exactly that term—her sister, part of herself, her good half. She is aware of the evil and corruption that fill her, of the fact that there is no light or hope left within her, only selfishness and emptiness, which she tries to fill by satisfying her desires. She sums it up with the telling words: Good is only a reflection of evil. Nothing more.

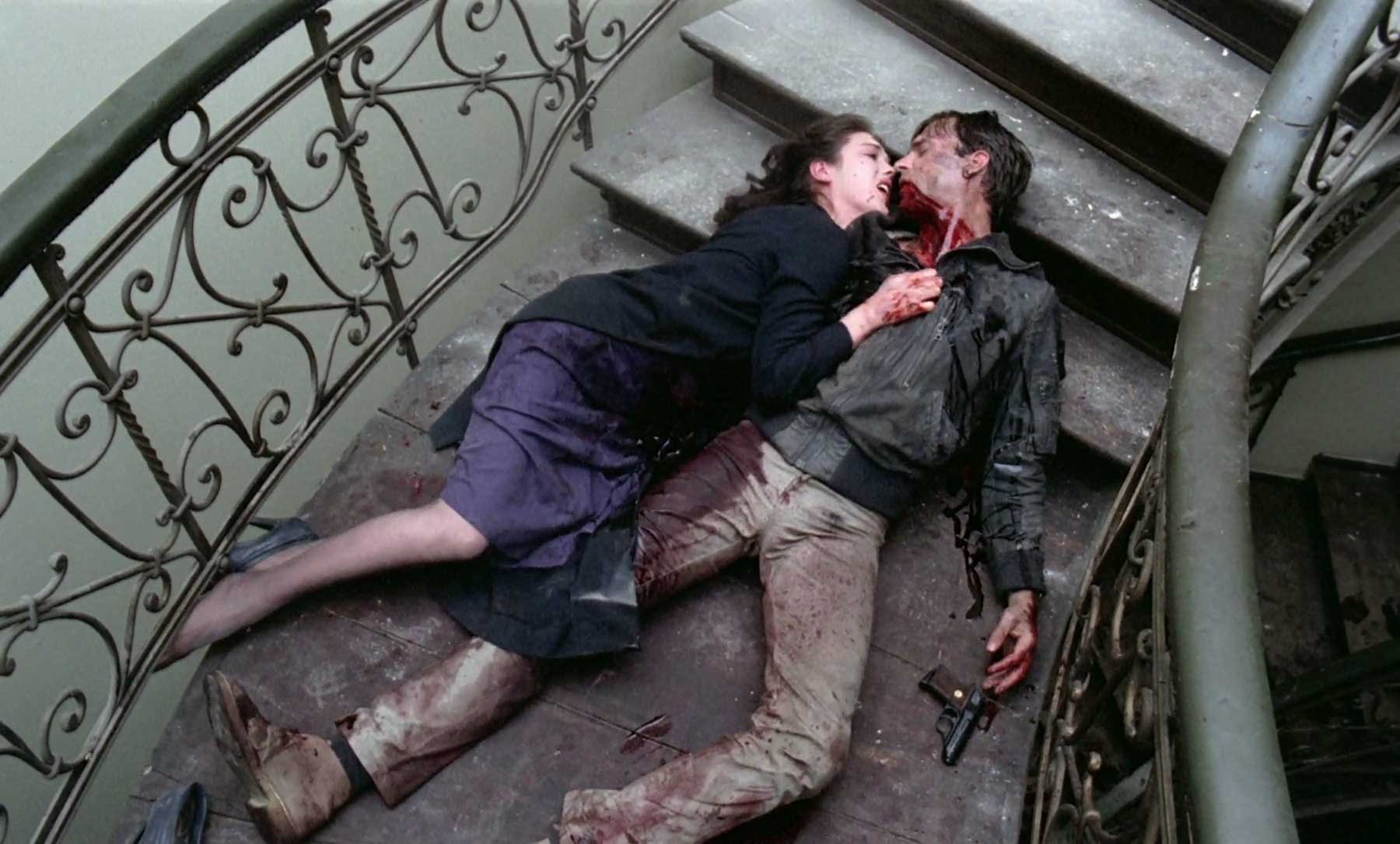

The second doppelgänger appears only in the penultimate scene of the film. Actually, we have seen him several times already, but we did not recognize him. He wasn’t ready yet. Now he climbs the winding stairs…

Żuławski was often considered a misogynist, and his attitude towards women is undoubtedly reflected in his films. He often portrays women as attractive monsters. Mantises, femmes fatales, disguised demons. The heroine of Possession is a model example of this. She embodies Freud’s vision of a woman—hysterical, emotionally unbalanced, following her senses, succumbing to physical temptation. She is the embodiment of evil, and she tries to corrupt the man. Freud called female sexuality the “dark continent” of the black continent, and this is how it is depicted in Żuławski’s film. As unexplored and undiscovered, but also dark, animalistic, and perverse.

In opposition to this image of a woman, a man should be rational, strong, and composed. But in Żuławski’s work, this is not the case. In confrontation with Anna, Mark is weak, sentimental, and just as emotional as the woman. When his wife leaves him, he turns into a dirty, sweat-soaked embryo, lying on crumpled sheets and shaking with delirious convulsions. He is struck with aphasia. He tries to speak, but only individual sounds and groans come out of his mouth. He is like a drug addict or an alcoholic going through withdrawal. He has psychosomatic withdrawal symptoms. He decides to win back the woman he is addicted to, even if it means begging for scraps of her affection.

That’s the kind of man we see in Possession. He is weak. He is a victim.

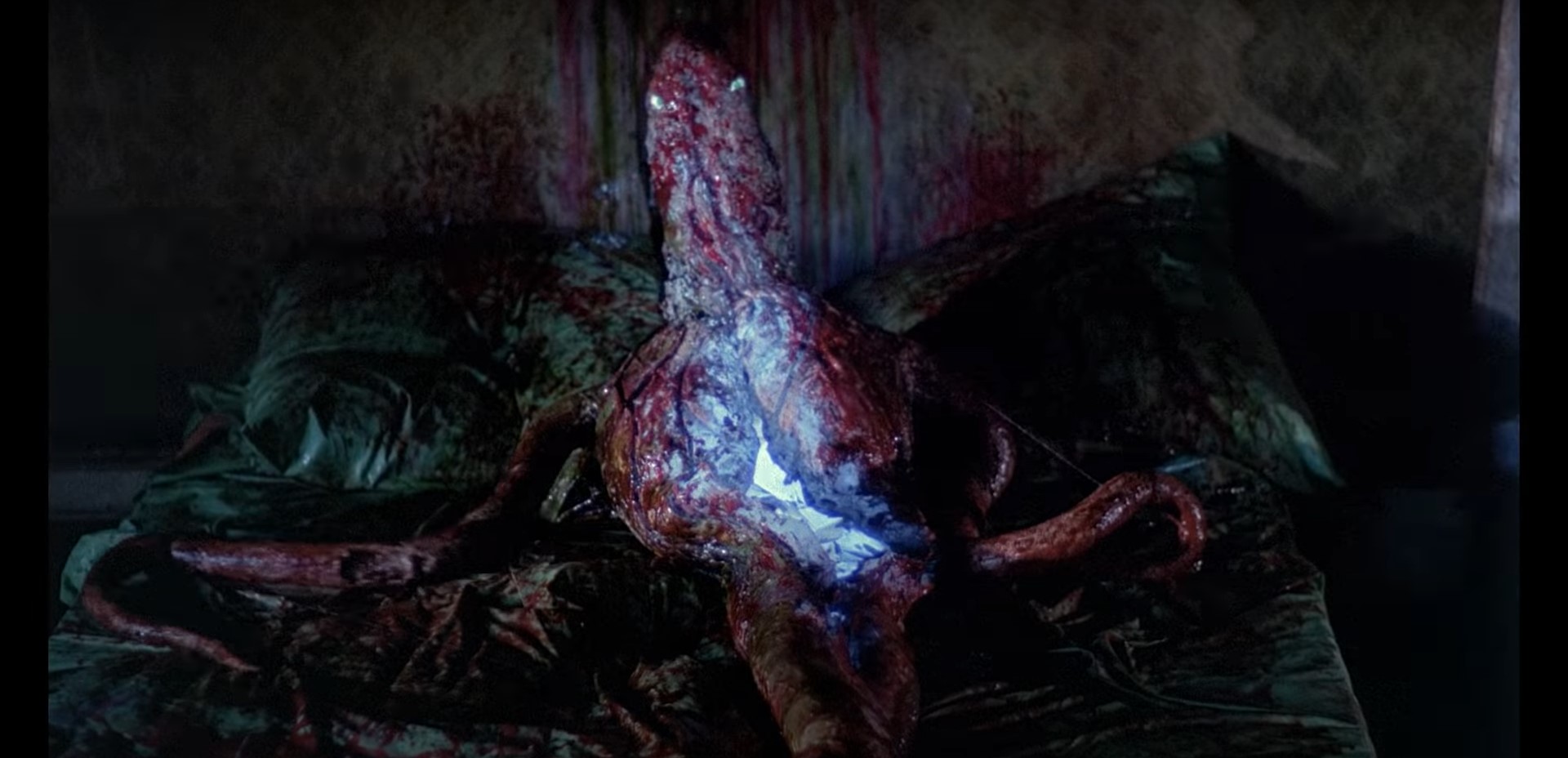

And his wife needs someone strong. Perhaps even brutal. Disappointment with her husband and lack of sexual satisfaction turn Anna into an erotic obsession. Frustration and despair take on monstrous proportions. Then the woman transforms into a possessed god, a mad demiurge, who molds from her fantasies and unmet desires the perfect lover.

This is how the doppelgänger, a better—from Anna’s perspective—version of Mark, is created. The original is weak and soft, the copy is powerful and ruthless. The doppelgänger has something magnetic and hypnotic about him. He is beautiful. But before he takes human form… Here is where the bloody horror begins. Anna weaves her love nest in an abandoned apartment in an old tenement house. Those who cross her threshold will not come out alive. The woman must protect her incomplete creation. The slowly transforming creature is first a giant phallus, then a humanoid with tentacles instead of limbs. Though not fully formed, mute and repulsive, the monster regularly satisfies Anna sexually.

The protagonist of Black Mirror, Martha, also got a new husband. But it did not make her life better. She continued to suffer and long for the real Ash because this second one was not exactly like her deceased beloved. Despite the vast amount of data programmed into him to make him as close to the original as possible, he was different. The fact that he looked like Ash never sufficed for a moment. But Martha loved and accepted her husband… Anna, on the other hand, loved only his appearance. Mark’s face, his body, and his voice—this was something familiar and close; everything else had to be perfected. Anna’s desires externalize. The image of her husband is just a shell, a vessel that she fills with her expectations, a reflection of herself. She creates a man unique, ideal for herself, her Animus. She does not expect her creation—like Frankenstein’s monster—to turn against its creator so quickly and want to go its own way.

Possession is, in the context of the doppelgänger representations that interest us, an unprecedented work. On one hand, it draws on the symbolism of the doppelgänger (the duality of human nature, the antinomic elements of good and evil within a person; the doppelgänger as an apocalyptic omen, a harbinger of death) and recreates the familiar links in the story of doppelgängers (the duel of the original and the copy, the struggle for identity). On the other hand, it completely breaks with the schema of the doppelgänger tale (yes, such a schema exists; based on the analysis of literature, a collection of characteristic and chronologically ordered elements present in every story based on the doppelgänger motif, which can also be successfully applied to film works; the classification’s author is Polish researcher Małgorzata Czermińska). Most often, the doppelgänger is a reflection of ourselves. For various reasons, we create our doppelgängers. Designing someone else’s doppelgänger is not very common. It is also rare for a director exploring the doppelgänger motif to simultaneously emphasize erotic themes so strongly. Death and the doppelgänger—always. Eros, Thanatos, and the doppelgänger—only in Żuławski’s work.

Possession ’s finale sends chills down the spine. Once again, let’s give the floor to the immortal Freud. He said that repetition—not only in the context of the doppelgänger but in a broader perspective, any repeated object or phenomenon—evokes paralyzing fear because through this factor, something that would otherwise seem innocent becomes uncanny and irresistibly reminds us of the idea of something fateful, against which we are helpless. It is this archetypal fear of the uncanny that makes the seemingly innocent ending of the film give us goosebumps.

Anna and Mark’s apartment. The sound of the doorbell rings. Helen, Anna’s better half (wait, is she really?), goes to open it. The little boy, who until now has been waiting for his father to return, becomes uneasy. If he had said “Don’t open!” once, we could interpret it in various ways. He is angry at his father for leaving him so long with a nice but still strange woman and wants to punish him. Maybe he is just teasing. He jumps up from the table and runs up the stairs, probably wanting to hide and provoke his father to play with him… But why does he keep repeating it? “Don’t open! Don’t open them! Don’t open…”

Do you dare to find out what awaits behind the door?

*

The above text is just one possible interpretation of Possession. Due to my interest in the doppelgänger motif, I have emphasized this element, but Żuławski’s film is a multi-layered work filled with symbolism that can be interpreted in many ways. As an existential drama dressed in the guise of horror fantasy. As a metaphor for the relationship between a woman and a man, a relationship in which good and evil, love and hate combine to create monstrosity. As a symbolic cinematic treatise on nymphomania and other sexual issues. As… Decide for yourself what it means to you.