MINDHUNTER Decoded: The Real Cases Behind Masterful Series

Take a closer look at the most interesting elements of the show, grouped alphabetically for better clarity.

A for Behavioral Analysis Mindhunter

Mindhunter

Mindhunter shows us the origins of the current FBI Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU), specifically the division within the NCAVC (National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime). Initially, it was the Behavioral Science Unit (BSU), which later transformed into the Investigative Support Unit (ISU).

The BAU uses behavioral analysis to build psychological profiles of criminals through crime scene analysis, victimology, the behavior of the offender, and their interactions with victims. This process leads to conclusions about who the criminal is, what drives them, what characteristics they have, and whether it’s possible to predict how, if at all, they will commit another crime. Based on this analysis, suggestions are made not only regarding the organization of the investigation but also about techniques for questioning potential suspects, as well as speaking with witnesses and victims’ families.

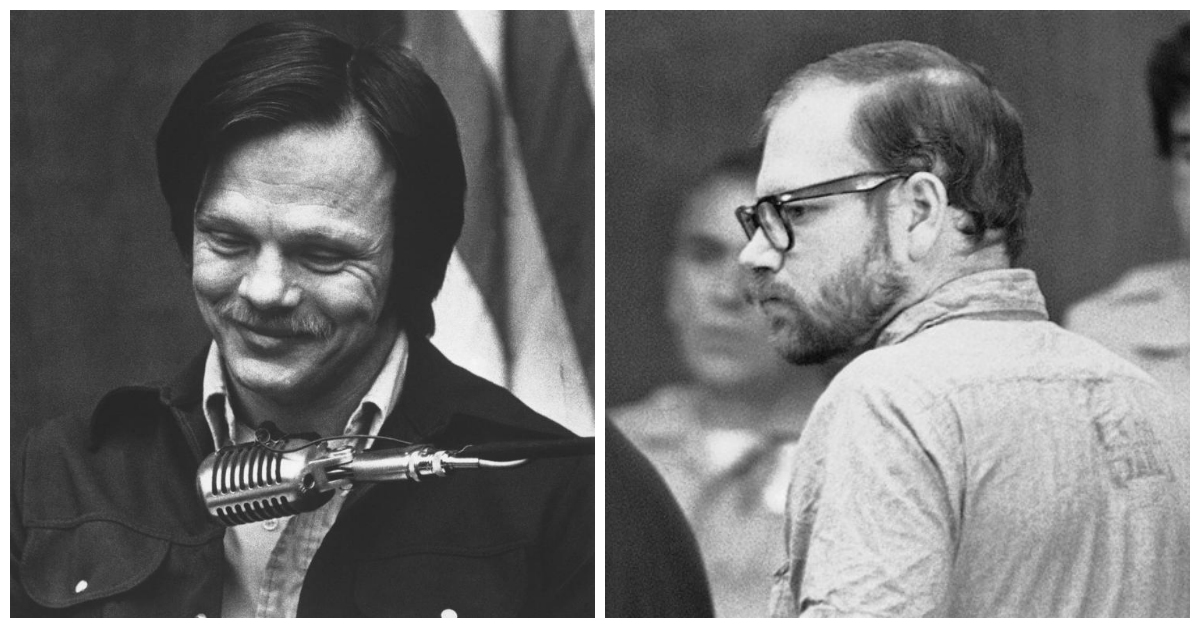

B for (warning, spoiler) BTK

Dennis Rader, the serial killer from Kansas, known as BTK (which stands for “Bind, Torture, Kill”). In the first season, we see brief snippets of him before the opening credits, and there are several mentions of his potential victims. Rader was convicted of ten murders he committed between 1974 and 1991. He detailed each of his crimes in letters sent to the police and newspapers. He was arrested in 2004, by chance—police were able to recover a deleted file from a floppy disk that had been sent to them, which was linked to Christ Lutheran Church. The file was marked as “last modified by Dennis,” and it turned out that Dennis Rader was the president of the church council.

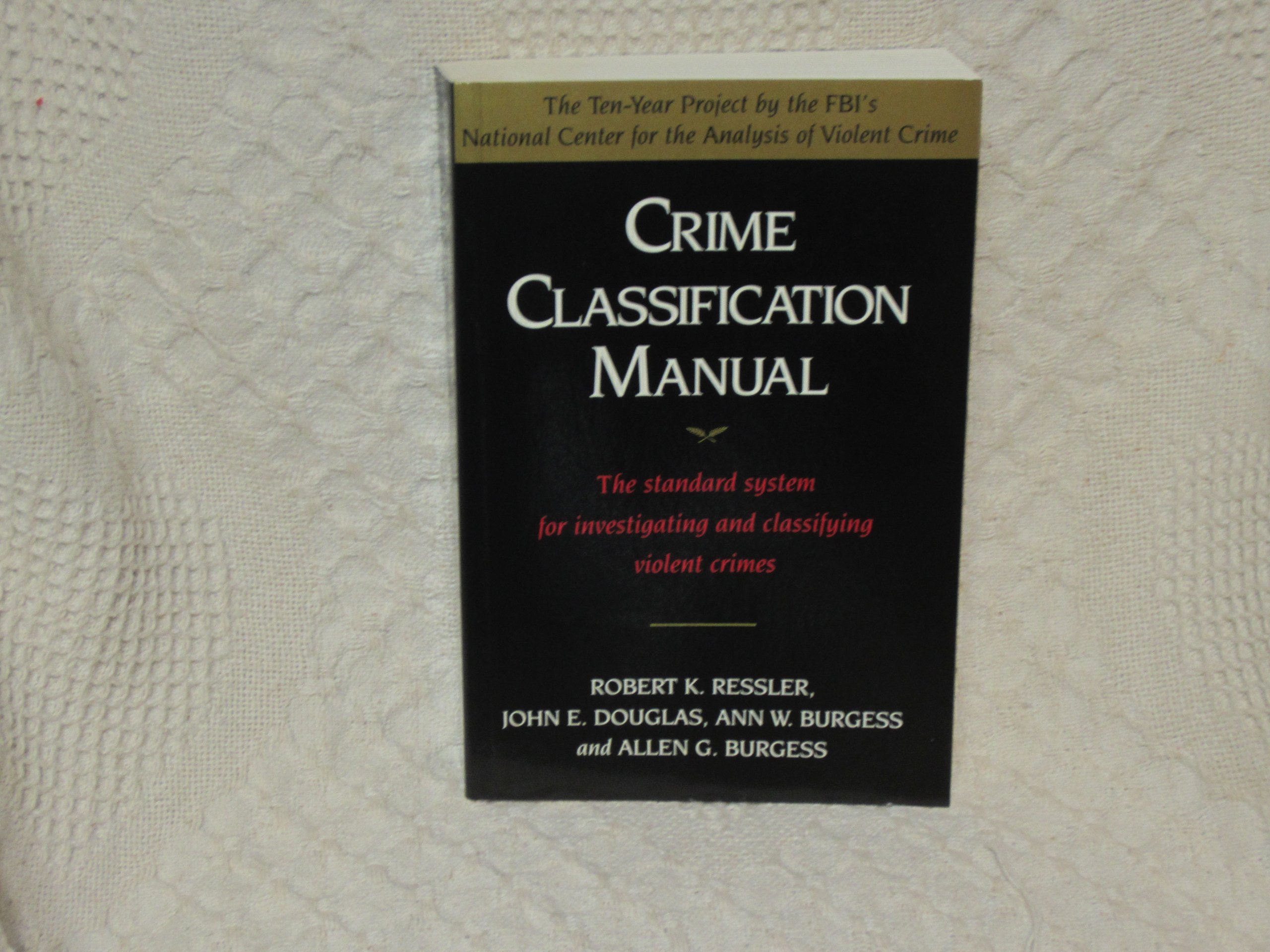

C for Crime Classification Manual: A Standard System for Investigating and Classifying Violent Crimes

The Crime Classification Manual, authored by John E. Douglas, Ann W. Burgess, Allen G. Burgess, and Robert K. Ressler, is considered the profiler’s bible. The first edition was released in 1992, the second, with an additional 155 pages, in 2006, and the third in 2013. The creation of this classification system is a direct result of the project we follow in Mindhunter. Of course, smaller publications had appeared earlier as well.

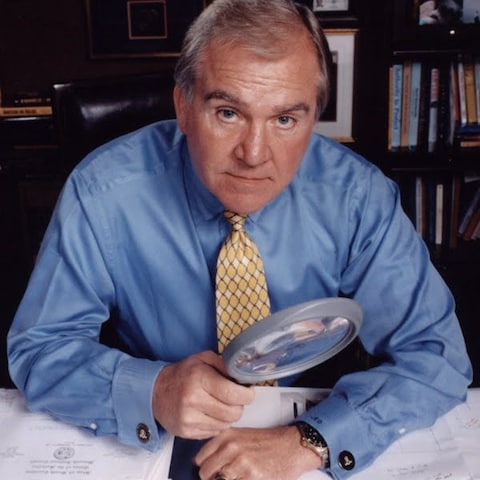

D for Douglas, John E.

The prototype of the character Holden Ford, portrayed by Jonathan Groff. A pioneer in behavioral analysis and psychological profiling, an FBI agent with over thirty years of service, and the author of the book that inspired the TV series. At one point in his career, he was practically the only active profiler in the unit, while his colleagues focused mainly on training. During that time, he handled over 150 cases simultaneously, including the Green River Killer, the Atlanta child murders, the San Francisco hitchhiker murders, Robert Hansen from Anchorage, who released his victims into the forest and hunted them like animals, and a serial poisoner from Connecticut. He paid a steep price for this intense workload, suffering from encephalitis and a stroke that left him paralyzed. However, he fully recovered and returned to work within six months—on a full-time basis. Today, he is retired but continues to write books, provide consulting services, lead training sessions, and offer expert opinions on high-profile criminal cases.

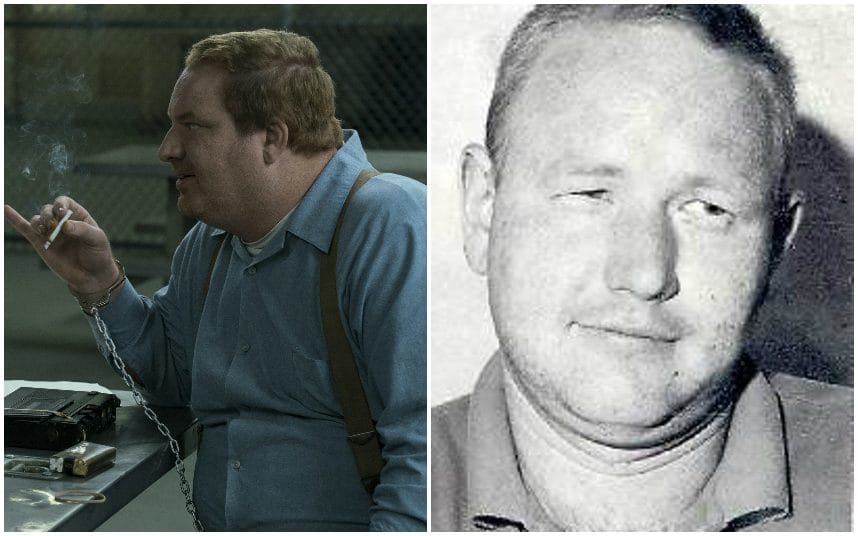

E for Ed

Ed Kemper, one of the most infamous serial killers in American history, often referenced in Mindhunter. His crimes, characterized by brutality and chilling calmness, became a subject of study for the Behavioral Science Unit. Known as the “Co-ed Killer,” Kemper murdered 10 people, including his mother and six young women, in the 1970s. His detailed confessions and calm demeanor during interviews with law enforcement made him a fascinating case for profiling. Kemper’s interviews, portrayed in the series, shed light on the psychological aspects of serial killers, contributing greatly to the development of behavioral profiling techniques. His case, one of the most discussed in profiling history, exemplifies the chilling efficiency of the methods developed by the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, as shown in Mindhunter.

F for Fincher, David

David Fincher, the visionary director behind Mindhunter, is known for his meticulous attention to detail and his mastery of creating atmospheric, intense narratives. Fincher, whose previous works include Se7en, Fight Club, and Zodiac, brought a unique touch to Mindhunter, infusing it with his signature style of tension, psychological depth, and dark visuals. His approach to the show focuses not just on the grisly crimes but also on the psychological intricacies of the characters, particularly the FBI agents. Fincher’s direction is crucial in making Mindhunter more than just a procedural; it becomes an exploration of the human psyche and the chilling minds of serial killers. His careful pacing and ability to build suspense while keeping the tension palpable have made Mindhunter a standout in the crime drama genre.

G for Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, a vibrant neighborhood in Manhattan, plays an important role in Mindhunter as a backdrop to some of the key developments in the series. In the late 1970s, when the events of Mindhunter take place, Greenwich Village was known for its counterculture, artistic communities, and alternative lifestyles. This setting contrasts sharply with the dark and twisted world of serial killers and criminal psychology explored by the FBI agents. The juxtaposition of these two worlds—the idealistic, progressive Village and the disturbing nature of the criminals under investigation—adds to the series’ atmosphere of tension and complexity. This setting also provides a glimpse into the personal lives of characters like Holden Ford, further highlighting the contrast between their work in the criminal field and their attempts to maintain a semblance of normalcy in their personal lives.

The Mad Bomber terrorized New York City during the late 1940s and early 1950s, and the police were completely powerless against him. For fifteen years, he carried out over thirty bombings, including attacks on train stations. Not knowing what else to do, the police turned to psychiatrist James A. Brussel from Greenwich Village for help. Brussel conducted a thorough crime scene investigation, analyzed the bomber’s letters and the locations of the bombs, and eventually provided the police with a note that became a landmark in criminology.

Look for a heavyset, middle-aged man, born overseas, Roman Catholic, unmarried, living with a brother or sister. When you find him, he will likely be wearing a double-breasted suit, buttoned up to the last button.

Brussel also concluded that the bomber was a paranoid man with an obsessive hatred for his father and an equally obsessive love for his mother, and that he lived in Connecticut. When George Metesky was finally arrested, it turned out that the doctor had only made one mistake: the Mad Bomber was living with two sisters, not with a brother or a sister. This case became a true milestone, and Dr. Brussel emerged as a pioneer who paved the way for those who would follow in the field of behavioral analysis.

H for Holden Caulfield

The protagonist of J.D. Salinger’s iconic The Catcher in the Rye, beloved in the United States. Over time, he has grown into an icon, one of the most important figures in 20th-century American literature. Above all, he became a symbol and a model for all young rebels. It’s no coincidence that Agent Ford bears his name. He rebels, with determination and effectiveness, against dead procedures, outdated protocols, rules, and regulations that no longer work and fail to deliver the desired results. He is a professional, but he is also very young – sometimes naive, sometimes recklessly brave, filled with enthusiasm in situations where more life experience would have bred bitterness and cynicism. He can also become absorbed with pride, filled with a sense of infallibility and invincibility. He believes he can do anything and will manage, that he can disconnect his mind from the flood of nightmares he faces. Like his literary namesake, Holden will, at some point, have to come to terms with the fact that some boundaries are impossible to cross.

I like literary inspiration

The series is based on the book Mindhunter by John E. Douglas and Mark Olshaker. When explaining what he actually does, Douglas (whose mother’s maiden name was Holmes, something he found an interesting omen) refers to literary examples. In his view, the first profiler in history was detective C. Auguste Dupin, featured in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue. Profiling as a technique also appears in two novels by Wilkie Collins—The Woman in White (1859) and The Moonstone (1868). As Douglas writes, however, it took more than a century since Poe’s story was published and half a century since the first adventures of Sherlock Holmes before the creation of psychological profiles ceased to be merely literary fiction and found its place in reality (see G for Greenwich Village).

J for Jerome Henry Brudos

Known by the press as “The Lust Killer” or “The Shoe Fetish Slayer,” Jerome Henry Brudos was convicted of four murders, though he likely committed more. He died in 2006 from liver cancer. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, he suffered from severe migraines and memory loss. He had a fetish for shoes and women’s lingerie from a very young age. As a child, he was constantly beaten and humiliated by his mother, who was disappointed that she had not given birth to a girl. After each murder, he would take photographs, put on high-heeled shoes, and masturbate. A pathological liar and manipulator, he changed his mind every ten minutes. In prison, his two main pastimes were continuously filing appeals and ordering catalogs of women’s shoes, which, he claimed, replaced pornography for him.

K for Kemper, Edmund Emil III

Standing over two meters tall, with a powerful build, solid mass, and exceptional intelligence, Edmund Kemper was a terrifying and fascinating figure. He had ten victims, including his mother and grandparents, and committed brutal, repulsive murders, including necrophilia, and possibly even cannibalism. What makes him even more chilling is his remarkable ability as a profiler. With the cold, analytical curiosity of a scientist, Kemper dissects his own behaviors and impulses. He collects data, compares, contrasts, and draws conclusions. These conclusions led him to believe he should never be released on parole, not out of guilt, but because his rational mind told him that, should he be set free, he would kill again. Since he allowed himself to be caught, wanting to end something that no longer brought him satisfaction, he saw no point in returning to the cycle of murder. It would be a waste of time for him and a loss to society, so it was better to stay in prison, where he was living quite well.

I admit, I liked Ed. He was friendly, sincere, sensitive, and had a sense of humor. As much as it was possible under the circumstances, I enjoyed being in his company, wrote Douglas.

This thought process intrigued John E. Douglas, who recalled his conversations with Kemper as sharp and penetrating. It’s worth noting that Kemper did not abandon his need for control and still enjoyed feeling powerful, for example, by suggesting that he could be a threat at any moment. Robert Ressler experienced this firsthand when he interviewed Kemper alone, and after the interview, he tried to summon a guard, but none arrived. “Relax,” Kemper told him, “It’s shift change.” He then added it would be funny if the guard entered to find Ressler’s severed head on the table. Kemper later claimed he was just joking, and perhaps he was, as there were no signs of physical aggression. Nevertheless, after that encounter, all interviews with inmates were conducted in pairs. This situation mirrors a similar moment in the series finale. Kemper, surprisingly, is the one who grounds Holden and shows him that he allowed his pride to momentarily blind him.

L for Local Police

A common motif seen frequently in films is the conflict between local law enforcement, who view federal agents with suspicion and distrust, and the FBI. However, in reality, things look different. Of course, no one is saying that such cases don’t occur—this can depend partly on the personality of the lead investigator—but it’s not the norm. When help is needed, especially in a race against time, personal animosities are set aside, because petty grievances or jealousy could lead to more victims. Contrary to what we often see in movies, local police and the FBI usually cooperate rather than getting in each other’s way, as their areas of jurisdiction differ (though in the 1970s, this wasn’t always clear for every police department).

When it comes to the Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU), John E. Douglas repeatedly emphasized that the unit functions in an advisory capacity.

Members of the Investigative Support Unit do not catch criminals. That’s the job of local police departments, which—given the immense responsibility they carry—do a good job with it. Our role is to assist the police in properly directing the investigation and then suggest proactive techniques, such as provocations, that help lure the criminal out of hiding. And when the police finally capture him—let me stress again, it’s the police who catch the criminal, not us—we try to devise a strategy that will help the prosecutor present an accurate profile of the defendant in court (John E. Douglas, Mark Olshaker, Mindhunter).

Although Holden Ford and Bill Tench experience suspicion toward the techniques they propose during their training trips—these were the early days, and distrust met them not only at the local level but also from their own colleagues at the federal level—we also see interest, questions, openness, and, most importantly, police officers who openly ask for help, overwhelmed by the weight of a difficult case.

M for Monte Rissell

The first rape he committed was at the age of fourteen. He was a serial rapist who, in 1976, turned into a serial killer. He was convicted of killing five women, all of the crimes committed before he turned nineteen. The appearance of Rissell in the series primarily serves to showcase the mechanism known as a “stressor,” “stressor trigger,” or “trigger,” which is particularly visible in his case. A stressor is a pivotal point in one’s life, a traumatic experience that leads the offender to start killing. However, it sometimes happens that a “stressor” and a “trigger” are not the same thing—for example, a long-term history of abuse could be a stressor, while the death of a loved one could be the actual trigger.

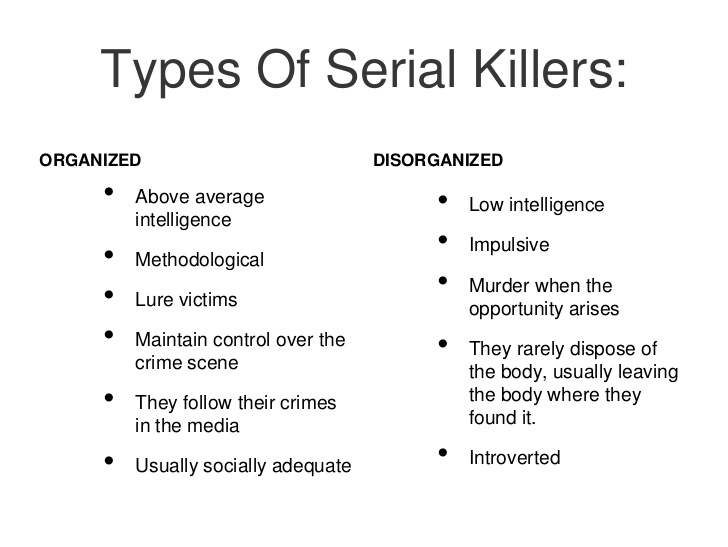

Rissell’s girlfriend broke up with him through a letter, and when he went to see her to talk about it, he found her with a new partner. Like many serial killers, he directed his anger at a substitute object that symbolized the person who had left him. Another rape wasn’t enough, and the woman he attacked, driven by survival instinct, tried to act as though she was enjoying the act. She thought it would save her, but it only enraged Rissell, reinforcing his belief that all women were treacherous sluts. That night, he killed for the first time, and with each subsequent victim, his fury and brutality only grew. He stabbed the last one dozens of times, estimating that there may have been even a hundred stabs. It is worth noting that Rissell was highly intelligent, but he was a disorganized criminal, which again proves that the degree of organization and intelligence do not necessarily go hand in hand (see O for Organization).

N for Necrophilia

Sexual paraphilia characterized by erotic attraction to corpses. According to research conducted among necrophiles, the most common source of this attraction is the need for a completely submissive partner who agrees to everything, often seen in individuals who lack control over their own lives and are dominated by strong personalities in their environment. In the case of serial killers, acts of necrophilia often serve to demonstrate absolute power over the victim, their final domination and humiliation. When Henry Lee Lucas was asked why he killed women and then had sex with them, he replied, “I like the silence and peace.”

A drastic example of necrophilia is the case of Ed Kemper, who desecrated the bodies of most of his ten victims, including his mother. In the series, the unbelievable brutality of Kemper’s acts is contrasted with the friendly, almost familial tone of the interviews conducted with him (see K for Kemper, Edmund Emil III, and E for Ed).

O for Organization

One of the most fundamental distinctions in classifying criminals is the division based on their level of organization. A commonly repeated stereotype suggests that a serial killer is a cold, sophisticated psychopath with a high IQ. However, this isn’t necessarily true. Indeed, organized offenders often have above-average intelligence. This type plans, anticipates, seizes opportunities, tracks victims, checks their surroundings, and brings tools with them. They often lead seemingly normal lives—holding jobs, maintaining comfort zones, having friends, and even spouses. Of course, this is a very general outline, supplemented by other elements stemming from case-specific analysis. In contrast, the disorganized type embodies mess, chaos, panic, using tools found on-site, and a greater likelihood of making mistakes and leaving evidence. This category often includes schizophrenics, psychotics, and individuals with lower intelligence levels. There are also “mixed” types and cases where, for some reason, an organized offender begins to escalate rapidly, losing touch with reality and, consequently, their organized behavior.

P for Podophilia

Podophilia refers to a sexual fetish or paraphilia characterized by a strong attraction to feet. Individuals with this fetish may find various aspects of feet sexually stimulating, such as their appearance, touch, or even activities like massaging or licking feet. While podophilia is often regarded as one of the more common fetishes, it can range in intensity from a mild attraction to feet to a full-blown obsession where feet become the central focus of the person’s sexual interest.

In the context of criminal profiling and investigations into serial offenders, podophilia, like other sexual fetishes, may play a role in understanding the behavior of certain individuals. Some serial killers or sexual offenders may have specific fetishes that influence their actions or fantasies, and these fetishes may become a part of their crimes. However, it is important to note that not everyone with a foot fetish engages in criminal behavior; like other paraphilias, it exists on a spectrum and can range from harmless preference to something that might impact a person’s relationships or behavior in unhealthy ways.

R for Ressler, Robert K.

Robert K. Ressler was a former FBI agent and one of the pioneers of criminal profiling and investigative psychology. He is best known for his work in the Behavioral Science Unit, where he played a significant role in developing techniques for identifying and understanding serial criminals. Ressler, alongside his colleague John E. Douglas, was instrumental in creating the framework for what would later become criminal profiling, which involves analyzing crime scenes, patterns, and behavior to help law enforcement identify potential suspects.

Ressler’s most notable contributions to the field include his extensive interviews with serial killers, which helped establish the profile of violent offenders, including understanding the psychological triggers and behaviors that led to their crimes. He is also credited with coining the term “serial killer” and helping define the criteria for this category of criminal. His work, along with that of Douglas and others, paved the way for the creation of programs like the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit, which focuses on studying criminal behavior to assist in law enforcement investigations.

In the context of the Mindhunter series, Ressler’s character is portrayed as a key member of the Behavioral Science Unit who works alongside Holden Ford and Bill Tench. He is depicted as the more pragmatic and grounded of the team, with a clear understanding of how profiling can be used to solve cases. Ressler is instrumental in guiding Ford and Tench in their interactions with serial killers, helping them to focus on the patterns of behavior that could provide insight into future crimes and suspects. His experience and contributions to the field make him a pivotal figure in the development of criminal profiling as a tool for law enforcement.

S for Speck, Richard

Richard Speck was an American serial killer who became infamous for the brutal murders of eight nursing students in Chicago in 1966. His crimes were particularly shocking due to the scale of the murders and the fact that he killed all of his victims in one night, leaving only one survivor. Speck’s life and the brutal acts he committed became the subject of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis, including in the work of FBI agents such as John E. Douglas and Robert K. Ressler. Speck’s murders were marked by extreme violence and a chilling lack of remorse. On the night of July 13, 1966, Speck entered the apartment of the nursing students, bound his victims, and forced them into one room before executing each of them. The only survivor, Cora Amurao, managed to escape, which helped authorities gather details about the crime. Speck was eventually caught when his fingerprints were found at the crime scene, leading to his arrest and conviction.

The case of Richard Speck became one of the more famous examples in the early development of criminal profiling, particularly in understanding the mindset of serial killers. His lack of remorse and the brutal nature of his crimes raised questions about his mental state and motivations, which were examined by investigators and profilers during and after his trial. His case, like others, helped shape the FBI’s approach to studying violent offenders, especially regarding the understanding of behaviors, triggers, and patterns in serial killers.

Speck was sentenced to death, but his sentence was later commuted to life in prison. He died in 1991 while incarcerated, where he reportedly had issues with violence and was involved in troubling behaviors within the prison system.

The killer of eight nursing students from Illinois plays a dual role in the series. Firstly, his case serves to distinguish between the concepts of serial and mass murder. Secondly, during his interview, it is the first time Holden Ford uses the controversial technique of establishing rapport through specific word choices. Indeed, it is only after mentioning “juicy pussies” that Speck pays attention to him. One of the most intriguing elements of Mindhunter is watching how new techniques are practiced and implemented right before our eyes, and we even witness the creation of the term “serial killer,” which today seems so obvious to us.

Speck became widely discussed again in the 1990s when an anonymous video tape was sent to a news outlet. The tape shows Speck in the company of a prison “guardian,” with whom he engages in oral sex and uses cocaine. Speck is wearing pink clothing and has enlarged, almost feminine breasts, which he achieved through hormone injections. This gives some insight into the method he chose for survival in prison. At one point, he states that he would be released from prison if anyone realized how much joy he was getting. When asked about the women he murdered, he casually admits that it “just wasn’t their day.”

T for Tool Box Killers

When Gregg Smith is considered as a candidate for joining the unit, Holden has serious doubts about him. Most importantly, he fears that Gregg might be a plant from “the higher-ups.” To discourage him and give him a sample of the type of tasks awaiting the BSU, Holden gives him an interview recording with Lawrence Bittaker and Roy Norris, known as the “Tool Box Killers.” He chose the strongest material he could think of (which is evident from Smith’s reaction). Bittaker and Norris kidnapped, raped, and murdered five girls between June and October of 1979. The victims endured unimaginable torture before their deaths, which is why the criminal duo earned their notorious name.

Throughout the trial, Bittaker never stopped smiling.

U for Uniform Study

The bone of contention between Tench, Ford, and Dr. Carr, who would prefer the entire project to be conducted according to her developed questionnaire. She comes from a perfectly reasonable assumption that it is difficult to talk about research without controlled conditions. The problem, however, is that the rigid framework of top-down questions is unlikely to break through the wall of hostility, disdain, or even skepticism. After all, they are just more “psychologists with their boring surveys” — who would care? Improvisation, which Ford is a strong proponent of (Tench is a bit less enthusiastic), can be risky when it is necessary to lower the language to the level of the subject (as in the case of Richard Speck) to reach them. Therefore, the questionnaire can only serve as a framework, a trigger phrase, because each situation is different. Wendy seems to not fully understand this, perhaps because she hasn’t personally participated in any of these conversations.

W for Wendy Carr

The fascinating psychologist, author of the questionnaire, and supervisor of the project conducted in the basements of the FBI, is based on the character of Ann Wolbert Burgess, a renowned scientist and one of the pioneers of techniques for dealing with victims of abuse, rape, and trauma. In reality, Burgess’s primary area of interest was the impact of childhood experiences on the later behavior of serial killers and juvenile delinquency. In the series, Dr. Carr is portrayed as a lesbian who hides her private life – this is a fictional element, but in reality, Ann Burgess also struggled with the need to constantly prove her professionalism in a male-dominated field. Wendy Carr is a strong, independent, and self-sufficient person who brings a strong female voice to the series. The whole unit fought for recognition, but for her, it was a doubly difficult battle due to her gender. This is symbolically reflected in the subplot with the cat, which Wendy feeds, deriving satisfaction from secretly helping a creature that hides from the world.

Z (ok, there is no Z)

What profilers observe daily, what they deal with in their everyday work, inevitably impacts their personal relationships. On one hand, they need their families because they require stability, warmth, normality, and a safety valve, as we all know what happens when you look into the abyss for too long. On the other hand, they see their loved ones in a completely different light. For instance, Douglas admits that he had difficulty caring about or even showing concern when one of his daughters had a mild fever, because his mind immediately brought up the image of disfigured child corpses on the autopsy table. Achieving normality is not easy, and it is a significant challenge for the people with whom the profiler shares their life. Mindhunter portrays this beautifully in the glimpses of Tench and Ford’s private lives. At one point, Tench explodes, strongly reminding his wife of what he deals with daily, throwing macabre photos in her face. She hugs him without a word, and he slowly fades away, apologizing for his outburst. This scene speaks volumes about the tension brewing inside Bill, about the experiences he is reluctant to share. Home doesn’t fully provide him relief, as he cannot find common ground with his autistic son, so he withdraws to avoid fighting one too many losing battles, for which his wife justifiably resents him. Only through the maturity of their long-term relationship, tested through many crises, are they able to cope and survive.

However, Holden is much younger, and when he returns home, his head is full of impressions. It’s not even that he can’t clear them away; he doesn’t want to – he wants to discuss everything with his girlfriend, confide in her, ask for her opinion. But in doing so, the line between his private life and his professional life dangerously blurs, and his attitude toward intimacy with his partner is influenced by what he has experienced and heard. Instead of seeing his woman in sexy high heels, he thinks about Brudos’s obsession with the footwear of his murdered victims. Even the jealousy Holden feels about a student spending time with Debbie is tinged with anxiety that someone could physically harm her (after all, so many women were hurt by accepting a seemingly harmless man’s offer for a ride!). Dealing with this is a skill that only experience provides.

“When a person professionally examines corpses and disfigured bodies (…), after returning home, they want to forget about it as quickly as possible, and certainly won’t bring up at dinner, ‘I was dealing with a fascinating murder case today. Let me tell you all about it.’ For this reason, police officers – with mutual understanding – have a soft spot for nurses. They understand each other well,” writes John E. Douglas.