Times have changed, he hasn’t… SAM PECKINPAH’S film ranking

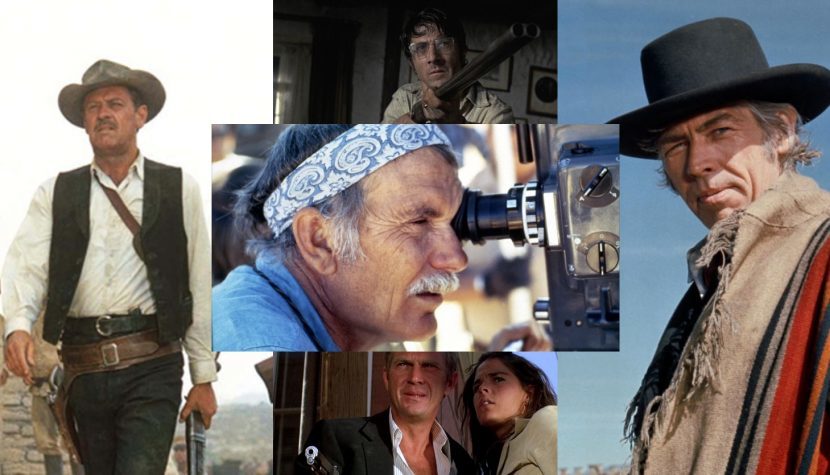

Sam Peckinpah (1925-1984) earned his position solidly. He started almost from the bottom in the television industry and gradually climbed upwards, intriguing his colleagues with his unparalleled imagination and creative inventiveness, but also annoying with his self-destructive lifestyle (alcohol addiction). To achieve excellent results on the screen, behind the scenes should stand not only professionals, but also people with iron patience. Fortunately, there was no shortage of such in Hollywood, which resulted in the creation of great classics that make up the first seven (half) of this list. The director, to whom the nickname Bloody Sam adhered, managed to gather around him a group of regular actors, unofficially known as Sam Peckinpah’s Stock Company (after The John Ford Stock Company). Its members included: R.G. Armstrong, James Coburn, Ben Johnson, L.Q. Jones, Warren Oates, Slim Pickens, Jason Robards and Dub Taylor.

What he was most successful at was finding a new language of expression for the ossifying genre that was the western. He became a leading revisionist in this most American of film genres. And even though he hit his time quite well, as the 1960s were a watershed in terms of the brutalization of genre cinema, he still stirred controversy, and from today’s perspective, it’s clear that he was ahead of his time. His attempt to create a film without corpses, Junior Bonner, brought neither artistic nor commercial satisfaction, so he remained in the theme of films about killing. He became a symbol of violent cinema, so much so that members of the Monty Python group dedicated their macabre skit to him (Sam Peckinpah’s ‘Salad Days,’ November 1972), in which Eric Idle calls the director “the expatriate from Fresno, California” and goes on to refer to Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs as films that present “utterly truthful and very sexually arousing portrayal of violence in its starkest form”. Then there’s a preview of the director’s “lighter” film, and it’s not Junior Bonner at all, but a grotesquely violent adaptation of the musical Salad Days (1954) by Julian Slade and Dorothy Reynolds.

Here is my personal ranking of all the Bloody Sam theatrical films, from weakest to best.

14. The Deadly Companions (1961)

After years spent in television, Peckinpah was given the chance to make a film for theaters. Brian Keith, with whom he had worked on the TV series The Westerner (1960), suggested Sam’s candidacy. The film starred Maureen O’Hara, sister of producer Charles B. Fitzsimons and also a great actress known for her roles alongside John Wayne (Rio Grande, The Quiet Man). O’Hara was negative about working with Peckinpah – the director, deprived of creative freedom, was completely lost, having no influence on either the script or editing. The screenplay is by Albert Sidney Fleischman, who wrote it based on his own novel Yellowleg (1960). It tells the story of a Yankee who hides the scars of an attempted scalping under his hat. He was mutilated by a drunken Confederate soldier, whom he finally finds, but a dramatic event stands in the way of his revenge. During a shootout with bank robbers, Yankee accidentally kills a child, the son of a red-haired saloon dancer. The woman insists on burying her son alongside his father in Siringo, where a dangerous trail leads through Apache territory.

It’s an unconventional idea to make the transportation of a child’s corpse the main theme. There was potential for an interesting character study here, as the author created four characters, each with a different motivation. One wants revenge, another wants money from the bank, a third looks lustfully at the widow, while the woman has unhealed internal wounds (she is considered an inferior breed of human being because she gave birth to a bastard child) and believes that burying her son alongside his father will end her mental suffering and allow her to live in peace. However, the film doesn’t have a lot of emotional weight, and you don’t feel any threat at all from either the companions or the Indians. O’Hara looks phenomenal on the screen, but this is mainly due to cinematographer William Clothier – the actress didn’t get adequate support from the director, and the script was not good enough to squeeze much out of it. Another thing is that Peckinpah was hired mainly because it was easy to make a figurehead out of a debuting director. He signed the film with his name, took the check and the rest of the team could blame the failure on the mistakes of the debuting director. Fortunately, this unsuccessful debut didn’t weaken Peckinpah’s character, but only strengthened his conviction that in this profession working with actors isn’t everything. To become a true director, he must vie for full control over the script and editing.

13. The Killer Elite (1975)

Agent Mike Locken is the protagonist of a thriller trilogy written by Robert Syd Hopkins, writing under the pseudonym Robert Rostand. The series includes The Killer Elite (aka Monkey in the Middle, 1974), Viper’s Game (1974) and A Killing in Rome (1977). Screenwriters Marc Norman and Stirling Silliphant made the adaptation of the first installment, and Peckinpah took it on probably because it contained his favorite theme – the fraternal relationship between two men that falls apart when one breaks the rules of fair play. Actors made famous by The Godfather (1972), James Caan and Robert Duvall, were enlisted for the production, and Monte Hellman (Two-Lane Blacktop,1971; Cockfight, 1974), whom Bloody Sam considered one of America’s best directors, was brought into the film editing room. However, Mike Medavoy, head of production for United Artists, was responsible for the final shape of The Killer Elite. The result was a film that critics described as a combination of Three Days of the Condor and Enter the Dragon.

The most important element of the plot is a conspiracy theory, according to which the CIA assigns contracts to private agencies, thus having more influence over the country’s politics than officially known. Mike Locken (James Caan) and George Hansen (Robert Duvall) are among the aces of such a private agency, but one of them unexpectedly changes sides – he kills a protected person and seriously wounds an accomplice, thus sending him into forced retirement. Doctors do not give the injured man a chance to recover fully, so his employers remove him from the list of active agents. However, a cripple can’t be the main character of an action film, so Locken recovers and even becomes an eastern fighting champion – he limps, but can use a cane efficiently. It’s clear that he must return to duty if only to get even with his treacherous accomplice.

The film lasts two hours, during which dialogue prevails over action, and unfortunately the spy intrigue doesn’t hold as much suspense as, for example, Three Days of the Condor. The characters are constructed according to a boring template and played without conviction. The execution is conventional, without flair or energy, because alcohol and cocaine interested the director more than the film’s script. Peckinpah’s good form can be seen in the ending, where we have slow-motion death scenes and Eastern martial arts involving ninja warriors. If the whole thing had been subordinated to the fight scenes, a better film might have been made, as the production included Takayuki Kubota (founder of the Gosoku-ryu karate school) and his students Hank Hamilton (7th dan) and James Caan (6th dan; yes, The Godfather and Misery star was a karate master, having practiced martial arts for 30 years under the tutelage of Grandmaster Kubota).

12. Convoy (1978)

Convoy is the logical continuation of a series of films aimed at car fans, initiated by Marlon Brando’s performance in Laslo Benedek’s The Wild One (1953). The first stage of the trend’s development was biker movies, which enjoyed success in the second half of the 1960s (Motorpsycho!, 1965; The Wild Angels, 1966; The Born Losers, 1967; Hell’s Angels, 1967; The Glory Stompers, 1967; Easy Rider, 1969). The second stage was films with cars in the foreground (e.g., Vanishing Point, 1971; White Lightning, 1973; Gone in 60 Seconds, 1974; Dirty Mary Crazy Larry, 1974; The Driver, 1978). Logically, then, from the perspective of the second half of the 1970s, there was a shortage of films for truck lovers (lorries appeared on the screen occasionally, e.g. in the thriller Duel and the comedy Smokey and the Bandit). Going by expectations, a niche series of trucker movies was created, which was also a result of the growing popularity of citizen’s band radio (CB). Truck drivers received their moments of fame in films: Breaker! Breaker! (1977), Citizens Band (1977), High-Ballin’ (1978), the Australian Roadgames (1981) and Peckinpah’s Convoy.

Despite mixed, mostly unfavorable, reviews from critics, the production was a huge financial success, unlike Peckinpah’s previous four films from 1973-1977. However, the director could not be satisfied, as he was fired during post-production and had no say in the final editing. He was not constantly present at the shooting stage either – due to his health problems, many scenes were shot by his friend James Coburn, who was hired as second unit director. Convoy is a likable classic that is fun to watch on subsequent viewings because of its gallery of charismatic characters and the compelling theme of rebellion against the police. However, Ernest Borgnine, who proved in Emperor of the North Pole (1973) that he can play a mean villain, here as the bad cop doesn’t give the impression of a man to be feared.

Some parts show a heavy directorial hand allowing (presumably) the actors to improvise. Scenes that were intended to entertain perform poorly, and there was also a lack of appropriate energy and tension in the action scenes. The only exception is an excellent bit involving stuntman Robert Herron, who, as Ernest Borgnine’s understudy, performs a daring car jump over a barn. The film has an unusual literary basis – it’s the song Convoy (1975), belonging to the truck-driving country genre, which in turn was created as a response to the popularity of advertisements for Old Home whole-grain bread. Launched in 1973, the ad campaign featured 18-wheeler truck driver C. W. McCall (Jim Finlayson) flirting with a waitress named Mavis (Jeanne Capps). The art director and copywriter was William Fries, also a songwriter and singer. The success of these spots (confirmed by recognized in the advertising industry Clio awards) led him to adopt the nickname of the truck driver from the ads, C. W. McCall, and later became an inspiration for Sam Peckinpah, co-creating (with musician and songwriter Chip Davis) a song about a convoy driven by a driver nicknamed Rubber Duck, as well as a sequel to that song Round the World with the Rubber Duck.

11. The Osterman Weekend (1983)

In the early 1980s, Peckinpah’s name still meant something and there were many actors wanting to work with him, but producers didn’t have a good opinion of him. He was falling into health problems through alcohol and drug addiction, and his directorial ingenuity couldn’t resonate through his explosive temper. His name looked good on the poster, after all, he was the creator of the unforgettable The Wild Bunch (1969), but on closer acquaintance he turned out to be a man difficult to work with, uncompromising and insolent. This was also found out by Peter S. Davis and William N. Panzer, who bought the rights to Robert Ludlum’s novel The Osterman Weekend (1972) and decided to give Peckinpah a chance despite his bad reputation. Although the director was battling illness, in addition to disliking Ludlum’s novel and disliking the script, he accepted the offer, hoping for a triumphant return to the industry or at least something that would improve his situation.

He managed to finish the film on schedule and not go over budget, which was already a success in a way. As usual, the trouble began when a coherent whole had to be created from the shot material. Edited according to Peckinpah’s vision, the film didn’t pass the test screenings. The producers hoped that the director himself would re-edit and shorten his work, but as a result of his refusal to do so, they fired him and organized a second edition themselves. Unfortunately, The Osterman Weekend proved to be a box office and artistic failure once it hit theaters, and what’s worse, Peckinpah could no longer rehabilitate for it – he died of heart failure at the age of 59 (December 1984).

Many critics consider this product to be the worst of the director’s career, but for the person writing these words it is, despite its flaws, an interesting piece of cinema, in which Bloody Sam’s masterful (albeit whiskey-shaking) hand is evident. There is a impressive spy plot that may seem incoherent, but there is a paranoid atmosphere and hallucinatory madness. In turn, the motif of confining the protagonists to a house and building tension between a small group of characters brings to mind Straw Dogs (1971). And, as always with this filmmaker, we have a good cast (Burt Lancaster, Rutger Hauer, Dennis Hopper, John Hurt), although we can’t speak of great acting performances, but rather of a successful weekend with friends. And even though the director complained to the producers for taking away his final say in editing, he still thought it was a good film. His opinion was shared by the French – the production was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the police/crime genre festival in the French city of Cognac (Festival du film policier de Cognac). A year earlier, the Grand Prix of this event was awarded to the makers of the popular action comedy 48 Hrs..

10. Junior Bonner (1972)

Between a violent thriller (Straw Dogs, 1971) and a dynamic action movie (The Getaway, 1972), the director surprised with a completely different film, both in subject matter and style. He shot it mainly to defend himself from being pigeonholed as a filmmaker of action and violence cinema. Taking a story from the rodeo community, he cast Steve McQueen in the role of Ace Bonner Junior, who returns to his hometown of Prescott, Arizona, for the Frontier Days parade and intends to compete in the rodeo one last time. In the process, he renews ties with his family, especially his father who dreams of fleeing to Australia. Father and son attached to tradition are confronted by Junior’s brother, Curly, an entrepreneur and real estate developer for whom tradition and family ties are less important than the profits to be made by destroying old places with a bulldozer to build new ones.

Although the production seems modest in terms of action, the budget (more than three million dollars) was close to the classics of thriller cinema made in the same period (Straw Dogs and The Getaway). There are impressive mass scenes, such as the parade and rodeo executed during Frontier Days, The World’s Oldest Rodeo, hosted annually by the city of Prescott, Arizona. The film took a financial loss, which may have been due to the fact that pictures such as Rodeo (1971, dir. Cliff Robertson) and The Honkers (1972, dir. Steve Ihnat) premiered before it, not to mention television productions exploring the theme. Thus, Peckinpah’s film didn’t seem interesting, even despite Steve McQueen’s participation. Especially since the critics’ reviews were not very enthusiastic. It’s worth noting that the film marks the great return to the cinema screen of two forgotten stars of American cinema, Ida Lupino (They Drive by Night, 1940; High Sierra, 1941) and Robert Preston (This Gun for Hire, 1942; Blood on the Moon, 1948). One of the most important roles played Ben Johnson, who – before he got into the film industry – was a rodeo rider.

9. Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973)

Although the 1970s were a very prolific period in Sam Peckinpah’s career, from the beginning of the decade his reputation gradually deteriorated due to alcoholism. The turning point for his standing in the industry was the western Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, based on a screenplay by Rudy Wurlitzer, which was shot in Durango, Mexico. Due to numerous problems, shooting took longer than planned and the budget is out of control. The film, edited under Peckinpah’s direction, was shown at pre-release screenings for critics, but at the official theatrical release a different version could be seen – edited under the supervision of James T. Aubrey, then president of MGM, who had the film shortened by 20 minutes. In 1988, four years after the director’s death, the 122-minute-long Peckinpah original was officially restored, and in 2005 a special version shorter than the director’s edition, but longer than the producer’s, saw the light of day.

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid is a grimly nostalgic western ballad about the legends of the Wild West. Legends repeatedly portrayed on cinema and TV screens – if only a few years earlier Andrew V. McLaglen portrayed them in the background in the film Chisum (1970). At Bloody Sam the characters look unorthodox, there is psychological depth and internal conflicts. There are many fine actors in the cast, masters of the background, but the camera – in keeping with the title – focuses on the two legends played by James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson, who have almost no scenes together. There are a few exceptionally successful scenes, such as the death of one of the characters to the accompaniment of the song Knockin on Heaven’s Door. The elegiac atmosphere, co-created by Bob Dylan’s songs, perfectly emphasizes the twilight of the era, which was not so obvious at the stage of the script (since the action takes place in the classic period, Billy the Kid died in 1881). In Peckinpah’s vision, it’s the twilight of the western genre, not the twilight of the Wild West. The values represented by the old American West have survived to the present day, as can be seen in parallel police thrillers that look like modern westerns.

Separately, it would be appropriate to mention those who are usually forgotten because they don’t have star names and appear in the background. However, without these distinctive faces it is difficult to imagine the history of westerns. In the film Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid almost the entire second and third planes are filled with these faces. In alphabetical order: R.G. Armstrong (From Hell to Texas, 1958), Elisha Cook Jr. (Shane, 1953), Jack Elam (Vera Cruz, 1954), Richard Jaeckel ( 3:10 to Yuma, 1957), L.Q. Jones (Buchanan Rides Alone, 1958), Katy Jurado (High Noon, 1952), Slim Pickens (The Sheepman, 1958), Barry Sullivan (Forty Guns, 1957), Dub Taylor (‘Cannonball’ in a series of 50 Class B westerns from 1939-1949) and Chill Wills (Rio Grande, 1950). Each shows his distinctive face here, and overall, the presence of so many western veterans in one film has a very positive effect on the nostalgic aura, imparting to viewers that longing for “the old, better times”.

8. Major Dundee (1965)

In addition to roles in historical films, Charlton Heston did well in westerns. His leading roles in Will Penny (1967) and The Last Hard Men (1976) and his supporting role in The Big Country (1958) are very successful, but it was Major Dundee that was particularly important to him. He was so committed to the project that he gave up his salary to finish it, and he liked the title character so much that he wanted to make it one of the best roles of his career. In doing so, he showed great forbearance and determination, as the director didn’t make his task easy at all. Even at this early stage of his career, Peckinpah betrayed a penchant for drunkenness, but he alienated people for other reasons as well, and was repeatedly thrown off the set (he was deprived of the opportunity to direct The Cincinnati Kid and The Glory Guys – he wrote the script for the latter). Heston really liked Peckinpah’s previous film, Ride the High Country. It was because of him that he wanted to participate in this project, believing in the director’s talent and realizing that the most important thing is the end result, not what leads up to it. Great films are born in pain….

Major Dundee was intended by its first author, Harry Julian Fink, to be a classic adventure western. With the support of Oscar Saul (adaptor of the play A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951), the script was enriched with a psychological portrait of a glory-hungry officer. The psychological side of the story is reminiscent of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, but instead of a white whale, there is an Apache tribe. Through Peckinpah, who also had his fingers in the script, there is a clear polemic with classic westerns, in particular the works of John Ford: Fort Apache (1948) and The Searchers (1956). It’s a rough, realistic film, quite brutal for the mid-1960s, being an instructive exercise before The Wild Bunch.

Shortly before shooting began, there were changes in the management of the Columbia studio and the new authorities decided to cut the budget and shorten the work schedule. Lack of money and time for such an inherently epic production must have generated a number of problems and, as a result, the story’s potential was not fully realized. This work can be summed up in the words: “The failures of some directors are more interesting than the successes of others”, because despite the shortcomings, there are flashes of genius here. It’s a noble defeat – like a battle, which, although it doesn’t bring final victory in the war, shows the strength of the army and its strategic capabilities. Nor did the many problems surrounding the production weaken Charlton Heston’s superb performance, providing a great counterbalance to John Wayne’s cavalry roles. It can also be added that the original theatrical version of Major Dundee has a pompous march music by Daniele Amfitheatrof along with a song written by Ned Washington, which John Ford or Howard Hawks would have loved to use in their film, but Peckinpah didn’t want it. That’s why a new soundtrack with music composed by Christopher Caliendo was added in the restored 136-minute 2005 version.