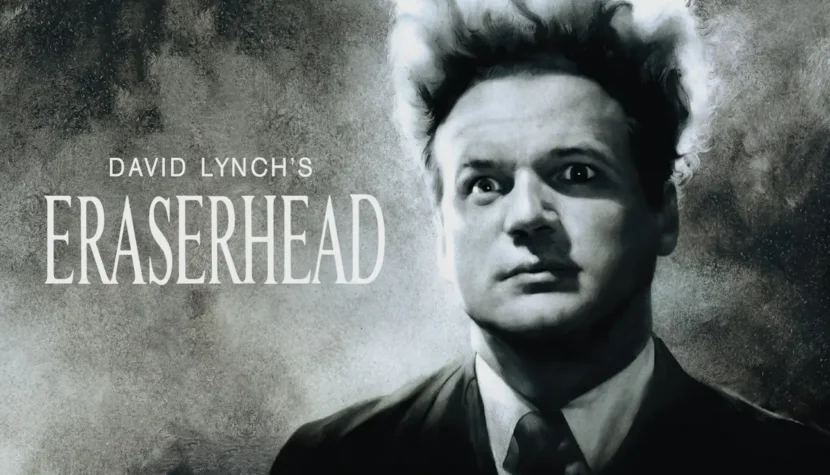

ERASERHEAD Explained: The Story Behind Lynch’s Masterpiece

Among the audience were the director’s friends and parents, his ex-wife and current wife, his daughter, people from the Institute, and those who had supported the project known as Eraserhead financially over the past five years. After 142 minutes of screening, the lights illuminated the faces of the audience. The room was completely silent, with only the sound of fluorescent lights buzzing.

INTO DARKNESS

In 1968, David Lynch’s daughter, Jennifer, was born. Shortly after her birth, it was discovered that the child suffered from a severe foot deformity. Before Jennifer fully recovered, she had to undergo several complicated surgeries and a rehabilitation process that immobilized her legs up to her waist.

Many analyses and reviews of Eraserhead treat this fact as the key to understanding Lynch’s first film. Jennifer is often associated with the monstrous baby resulting from Mary and Henry’s relationship, and the film is interpreted as a “metaphor for the fear of fatherhood.” However, this is an oversimplification. It’s not just that Lynch never turned his back on his daughter (Jennifer considers him her best friend and fondly remembers her childhood with him). The problem lies in the very approach to discussing the film. There is no universal key to Eraserhead that will unlock all its secrets. Some mysteries can be unraveled, but others can only be opened by Lynch himself, who has often emphasized that Henry Spencer’s story is his most personal film.

The fears, obsessions, thoughts, and themes in Eraserhead had been growing in Lynch since childhood. Even though he describes his early years as happy, the idea of a home where something is amiss has always been central to his art. Despite the love from his parents, Lynch admits he felt ambivalent about the very concept of a home. While he valued its safety and privacy, he also sensed a feeling of confinement, almost a claustrophobic fear. This dissonance likely led to his fascination with the cracks in seemingly perfect images (a subconscious belief that beneath flawless surfaces lies something darker and less friendly).

In the early 1950s, Lynch was playing with other children near a forest cabin in Idaho when a sound emerged from the trees—a terrifying, deep, haunting wail, unlike any human voice or animal sound, as Lynch described it years later. Adults and children froze, listening to the eerie noise. The silence was broken by Lynch’s mother, who said, I hope it’s a friendly sound. A few years later, Lynch played in his perfectly manicured garden, reminiscent of the one in Blue Velvet. Everything seemed ideal until Lynch approached a tree and noticed it swarming with red ants. Since then, Lynch often says that if you look closely at anything, you’ll always see red ants—you’ll always see the cracks.

The world of Eraserhead is a journey into a reality where ants exist dangerously close to humans, and eerie sounds are almost always present. It’s the same world we entered in Twin Peaks’ Red Room or observed in the prologue of Blue Velvet. The visit to Henry Spencer’s world is what Lynch calls “entering the darkness.” But darkness and blackness are not necessarily evil, because “it’s precisely in the dark that the stars shine brightest,” a Lynchian symbol of the absolute, safety, fulfillment, and a great mystery. (Anyone who has seen the epilogue of The Straight Story knows what I mean.) What led Lynch to venture into such dark territories?

THE PHILADELPHIA STORY

After Jennifer was born and Lynch married Peggy, they bought a house in Philadelphia. Twelve rooms, three floors, and thirty-seven large windows—all for $3,500. The low price wasn’t because the house was a ruin but because of the extremely hostile neighborhood, filled with factories, smoke, railroad tracks, and 24-hour dive bars. One night, a group of men broke into Lynch’s home, and the terrified director chased them away with a sword he kept by the fireplace. After that incident, Lynch became increasingly anxious. A second break-in occurred when someone entered through the basement window. Given the neighborhood, the police showed little interest in finding the culprits.

In Philadelphia, Lynch witnessed drunken brawls, saw children pleading with their parents to come home, and even saw people thrown from moving cars. But above all, he witnessed a murder. A teenage gang attacked a family crossing the street. A young boy tried to defend his sister and mother but was killed by several close-range gunshots to the head. The chalk outline of the body lingered on the street for five days.

While living in Philadelphia, Lynch worked at a printing shop (just like Henry in Eraserhead). He didn’t earn much, and he had to support his wife and child. Each day was filled with fear for his family’s safety, and Lynch struggled with depression over not being able to make more films (until an unexpected grant for The Grandmother broke the monotony). Lynch recalls that he and Peggy lived cheaply but in a city full of fear. There’s no surprise, then, that Lynch refers to Eraserhead as My own Philadelphia story.

It was this city that most influenced Lynch’s creative development. The experiences of 1967-1968, combined with themes that had always troubled him (like childhood demons), led first to the creation of The Grandmother and later to Eraserhead. So, what can we find in Eraserhead?

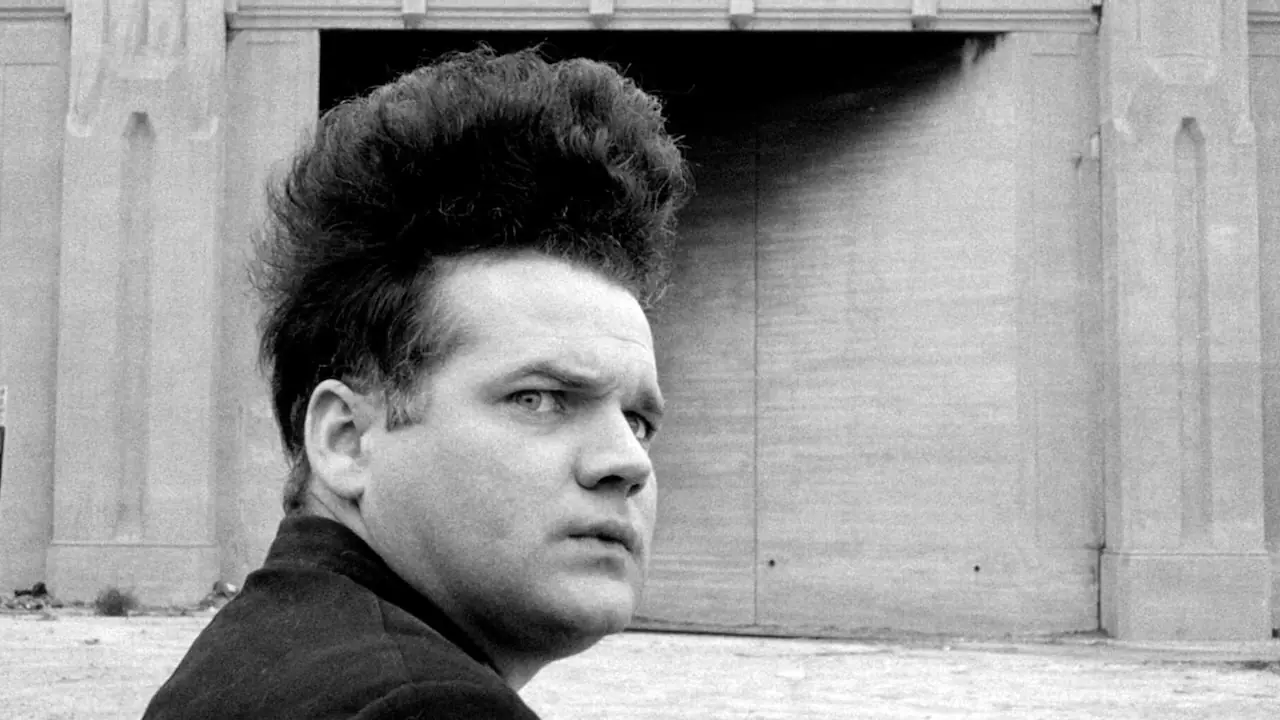

I AM SO AFRAID

Henry Spencer (a brilliant role by Jack Nance) is essentially David Lynch. This is revealed not only by the characteristic attire that serves as the director’s trademark but also by many other nuances. For instance, on Henry’s nightstand, there’s a pile of mud – a similar “sculpture” existed in Lynch’s home for several months (he molded it with his daughter). Henry’s fascination with the texture of mud/earth is also evident when he strolls among the mounds on his way to his apartment. In his mailbox, Henry finds a seed, reminiscent of the one discovered by the protagonist in The Grandmother, and in Lynch’s real life, seeds are closely associated with his family home and his father’s work. Henry’s relationship with Mary is troubled, just as Lynch’s marriage with Peggy was. Henry encounters a seductive woman from the apartment across the hall – Lynch, too, grappled with guilt over his affairs during his marriage. In Henry’s world, a child appears unexpectedly – Peggy’s pregnancy and Jennifer’s birth were also shocking to the young parents. Lastly, the number on Henry’s door is 26, precisely the age at which Lynch began working on Eraserhead. Countless more similarities can be found, of course.

Thus, at the center of Eraserhead stands David Lynch himself, but a broader perspective reveals a much more complex picture. Lynch’s features are practically present in every element of the film, which becomes a plunge “into the darkness” of his own mind. Following Henry’s story, we witness David Lynch exploring his own psyche, only to discover with horror that he doesn’t understand any of it. Henry is utterly lost. He realizes something is happening around him, that something is lurking, but he has no idea what it could be. His constant glances over his shoulder, his frightened, bewildered, or simply sad expression, and his compulsive urge to inspect everything closely and meticulously all indicate that Henry is trying to find some clues. Unfortunately, he cannot piece together the elements that cross his path. Henry is doomed to wander.

The space he navigates is shrouded in perpetual darkness, which, in the context of the earlier paragraphs, is hardly surprising. Lynch doesn’t guide us to a world of neatly trimmed lawns and white picket fences but delves into unsettling and inexplicable realms. It’s a journey through the Jungian Shadow, materialized in a form filtered through Lynch’s memories and emotions of Philadelphia. Amid the factory-lined streets, drenched in smoke and steam, Henry stumbles upon more of Lynch’s experiences – wandering through various corners of his mind.

The dominant emotion in the world of this “mental Philadelphia” is fear, understood not as simple terror but as a constant feeling of confusion and uncertainty. Wandering through this world of red ants resembles the experiences in Wojciech Has’s The Hourglass Sanatorium (Lynch considers Has’s films to be masterpieces). Much like Has’s protagonist, Lynch’s hero bounces from one memory to another, and sometimes these experiences begin to spiral out of control and take on a life of their own. Lynch offers a multitude of such phenomena, with the most prominent being the city, as mentioned before, the child, the Man in the Planet, and the Lady in the Radiator.

The figure of the child should not be seen as a reflection of the relationship between Lynch and his daughter. Instead, it is a manifestation of his fears and guilt, which – despite everything – is a miracle. From the first time he gazed into his daughter’s eyes, Lynch knew that something extraordinary had happened. However, problems also arose – how to protect a child in the reality of Philadelphia, how to provide a good life when money is scarce, and whether he should abandon art for a stable, better-paying job. Lynch felt guilty about not being able to give his child what his parents had given him. Out of all this emerged the monster – a bizarre fusion of fear, wounded conscience, and love, for in Lynch’s world, when something “goes wrong,” monsters inevitably appear. Moreover, it’s not only the child that reminds us of Lynch-Henry’s guilt. The repeated appearance of sperm-like creatures, the desperate attempts to destroy them, and, on the other hand, the care for the child’s fate perfectly illustrate this dynamic.

The Man in the Planet, considered by many to be the most enigmatic element of the film, seems to simply be a personification of Eraserhead itself. Covered in strange growths (Lynch’s father battled similar growths during his tree research), he exists on a desolate planet. There’s a huge hole in the roof of his house. The home is no longer a shelter; something has gone wrong. The Man in the Planet sits curled up like a frightened child, peering through a shattered window. In front of him are levers, with which he might potentially influence Henry’s fate. However, by the film’s end, we learn that he cannot control them. The Man in the Planet is Lynch, Henry, and the interior of their minds.

Finally, there’s the Lady in the Radiator, who appears in Henry’s world entirely unexpectedly. With an innocent smile, she crushes his guilt (stomping on the sperm-like creatures) and is the only character in the entire film to smile sincerely (excluding the grotesque grimace of Mr. X, Mary’s father). Lynch claims that she wasn’t part of the original script. The idea emerged only after Lynch achieved peace of mind through meditation. Lynch’s version is confirmed by his wife, Peggy. Regardless of this fact, one thing is certain – the Lady in the Radiator represents an exit from the realm of red ants and Philadelphia nightmares. In the film’s finale, Henry finally closes his eternally frightened and questioning eyes, and a sense of relief appears on his face. The Lady in the Radiator’s embrace ends his wandering, drives away the temptress from the room across the hall, and leads to the downfall of the Man in the Planet. A chapter comes to an end.

But what does this mean for Lynch? Most likely, it represents the attainment of inner peace. Emerging from the Shadow does not, however, imply its ultimate annihilation. Eraserhead will always remain an integral part of the director’s psyche. Thanks to the embrace of the Lady in the Radiator, the situation has become more bearable. Henry began to understand much more, and Lynch became convinced that delving into the darkness sensitizes us to the rays of light that we usually overlook.