DUEL Deciphered: Spielberg’s Horror on the Road

However, his first experiences were as a regular television director at Universal, where his task was to deal with actors on set and where he had very little creative control.

Warning – the text and images contain spoilers.

In these conditions, Spielberg made his debut, having the honor of directing Joan Crawford in Eyes (1969), the pilot episode of Rod Serling’s TV series Night Gallery. The following year, he directed the episode The Daredevil Gesture for the series Marcus Welby, M.D.. In 1971, Spielberg directed another Night Gallery episode titled Make Me Laugh. The next year, Spielberg’s work appeared on television with the episode L.A. 2017 from The Name of the Game series, two episodes of The Psychiatrist, the first episode of Columbo titled Murder by the Book, and the episode Eulogy for a Wide Receiver from the series Owen Marshall: Counselor at Law. Duel

In 1971, Spielberg’s assistant picked up a copy of Playboy, which featured Richard Matheson’s short story Duel, about a driver being pursued by a massive truck. At the same time, Matheson (co-author of the Twilight Zone series) had already completed the screenplay for the story, which was set to be produced by Universal Television. Spielberg met with producer George Eckstein, who reviewed the young 23-year-old’s work, and after three days, entrusted him with the direction of the project.

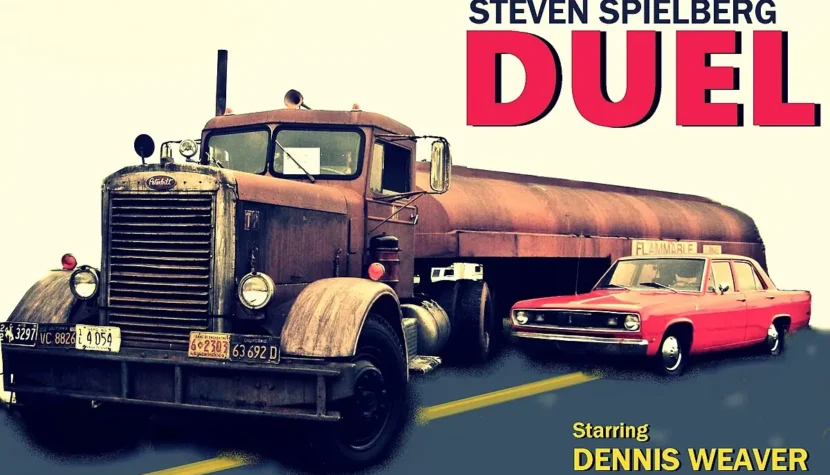

David Mann drives his red Plymouth Valiant on a long journey through the American wilderness. A life failure, he listens to the radio, talks to his wife on the phone at a gas station, and wants to reach his destination as quickly as possible. Along the way, he overtakes an eighteen-wheeled, dirty, and smoking tanker. This seemingly minor episode soon turns into his worst nightmare. The truck’s path continuously crosses David’s, with the anonymous driver doing everything in his power to eliminate the seemingly insignificant car. Finally, pushed to the brink of mental breakdown, David finds his inner strength and faces his pursuer head-on, concealed behind the dirty windshield of the truck’s cab…

Many renowned directors began their careers with films they’d rather not acknowledge. Even the greatest started this way—Kubrick (Fear and Desire), Hitchcock (The Garden of Delight), and Cameron (Piranha II). But Spielberg had a stroke of luck. Thanks in part to producer Barry Diller from ABC (which aired the film produced by Universal), Spielberg had the opportunity to direct his feature television debut, creating something akin to the best action cinema. Spielberg took full advantage of this opportunity with the bold, audacious confidence typical of a young filmmaker. Based on storyboards (some drawn by Ed Verraux, who later designed the sets for Zemeckis’ Contact), Spielberg masterfully crafted the desperate struggle of a life-weary, cowardly man facing an irrational threat.

Much like in Psycho, the destination quickly becomes irrelevant. The course of action is dictated by a random encounter on the road. However, the greatest strength of Duel is not the psychological conflict of David Mann, but the technical execution of the situation. In a way that is typical of horror films, Spielberg treats the dirty truck as a living, breathing monster bent on a senseless vendetta, attempting to destroy the innocent victim. The truck driver has no face; we only see his hands (and, at times, his legs in cowboy boots). There’s no attempt to reason with the pursuer. Like the Terminator, the truck driver has only one goal. The nerve-wracking spectacle is also filled with contradictory signals. David, convinced that the truck will destroy a school bus filled with noisy children, unsuccessfully tries to warn its driver. Meanwhile, the menacing tanker unexpectedly saves the bus full of kids from trouble, only to resume its pursuit of David.

Dennis Weaver, playing David Mann, deliberately looks and acts in a way that gets on the viewer’s nerves, and he was cast against Spielberg’s wishes. The old, dirty Peterbilt 351 truck also went through its own casting process. Spielberg chose it from several vehicles, primarily because the engine was placed in front of the cab, giving the hood the appearance of a ghostly face. To make the truck unequivocally associated with the villain, the crew would dirty the entire hood every day with dramatic oil streaks, and the grime on the cab’s windows was not accidental either. The eighteen-wheeler was meant to be a literal monster. Behind the wheel was experienced stunt driver Carey Loftin (Bullitt). Dennis Weaver’s stunt double driving the red Plymouth was another talented veteran, Dale van Sickel.

The studio gave Spielberg only 10 days to shoot, as they had planned for all the outdoor scenes to be filmed by a second unit in three days, with the rest of the movie being shot in the studio, with the actor in a car mock-up in front of a rear-projection screen. Spielberg rejected this absurd method of working and insisted on filming everything outdoors, with Dennis Weaver driving a real car on real roads. Before production, he mapped out the entire action, along with a detailed storyboard. His determination was supported by flawless adherence to the shooting schedule during the first three days of outdoor filming, 100 kilometers from L.A. That’s when the studio agreed to the young man’s ideas. Most of the car chase shots in the film were prepared in a very simple and time-efficient manner. Spielberg set up several cameras along each stretch of road, filming both vehicles as they passed in sequence. The cameras were then moved to the other side of the road to capture the same sequence, but in the opposite direction, with a different background. This method allowed Spielberg to create up to 10 shots from two passes along the same stretch of road, which were then inserted in various places throughout the film (although it is worth noting that the attacking truck is almost always shown from the right side of the frame, charging to the left; this is the same technique James Cameron used for car chases in Terminator 2. Apparently, there is a psychological justification for this, as we read from left to right — when something happens in the opposite direction, it subconsciously signals danger).

In addition, the crew was joined by Pat Hustis, the creator of the car used to film the famous car chases in Peter Yates Bullitt (1968). This vehicle was equipped with a very low-mounted camera platform, allowing for dramatic shots almost at road level. To shoot the spectacular final scene, Spielberg enlisted as many as seven camera operators, but he selected just one flawless shot from all the footage, showing the truck falling off the cliff. The monster truck’s driver, Carey Loftin, drove the vehicle right up to the edge of the precipice, as a hastily constructed device designed to prevent it from losing speed failed to work. Loftin jumped out of the truck at the last moment, which is visible in the finished film as the open truck door. Based on this, one could build a somewhat lighthearted, yet surprising, argument that contradicts the filmmakers’ intentions—that the film’s driver survived, and that David Mann’s wild joy is somewhat premature. Fortunately, no one tried to make a sequel based on this detail…

The footage was shot in just 13 days, which, given the level of difficulty and the modest technical and budgetary resources ($425,000), remains an almost unbelievable achievement. Spielberg was given 25 more days for editing and sound design. He managed this with the help of five talented editors, who worked simultaneously on assembling the various sequences. The iconic shot of the truck falling into the ravine was sound-enhanced with a roar taken from the classic Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) by Jack Arnold. Spielberg reused this sound in a nearly identical scene when the dead shark falls to the bottom of the ocean in Jaws. Duel, which premiered on November 13, 1971, was met with unanimous praise. It was decided to release the film in European cinemas. However, for this to happen, the film needed to be extended to 90 minutes, instead of its original 74. Spielberg again called Dennis Weaver to the set, found a near-identical truck, and filmed an exciting scene where the Plymouth is pushed directly into the path of a passing train, an episode with the school bus, and a phone conversation between Mann and his wife. Additionally, based on previous materials, he expanded the opening sequence and added more of David Mann’s off-screen thoughts.

In his action-packed debut, Spielberg already included a character element that would appear throughout his later work. David Mann is portrayed as a morally weak, cowardly jerk who can’t even defend his own wife from an attack by a stranger (this fact is revealed during a phone conversation with his fed-up wife). The figure of the incompetent husband-father, degraded by the wife-mother or completely absent from his own family’s life—drawn from Spielberg’s own youth—will return in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Roy Neary distances himself from his family to search for Devil’s Tower), E.T. (Elliot’s father abandoning the family), Empire of the Sun (Jim longs mostly for his mother), Hook (Peter Banning has no time for his children), and even in the comedic 1941 (Ward Douglas literally destroys his own home during an attack on the Japanese).

Formally, Duel features several cinematographic and editing tricks that would later become characteristic of Spielberg, such as his famous vertical crane camera shots. Towards the end of the film, during the decisive moment of David’s internal struggle, Spielberg executed (already tested in Eyes) an editing maneuver involving several quick close-ups of the main character’s silhouette and face—this trick would later be replicated in E.T., in the shots of Elliot looking at the police raid just before the bikes take off into the air. The gas station with hoses and spiders in cages appeared once again in Spielberg’s 1941, along with its owner, played by Lucille Benson in both films. The scene in which the elderly couple refuses to help David was repeated in Spielberg-produced Back to the Future (1985) by Robert Zemeckis. The elderly actors also appeared in Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Many shots from Duel were literally copied by George Miller in the Mad Max trilogy (although, on the other hand, can you shoot car chases on intersecting desert roads any other way?). Both vehicles from Duel unexpectedly returned in the episode Never Give a Trucker an Even Break of the 1978 The Incredible Hulk series. In this other Universal TV production, the exact same red Plymouth and Peterbilt tanker were shown, and authentic chase footage from Spielberg’s film was recycled.

As for Duel, it became a part of film history as one of the most thrilling action films in the road movie genre. In Spielberg’s career, this film was overshadowed only by Jaws, made four years later (by the way, the shark was a sort of variation on the truck), as the 1974 drama The Sugarland Express—despite solid execution, good acting, flawless direction, and staying within the road movie genre—has been considered one of Spielberg’s weaker films, and certainly not what one would expect after Duel.

From Duel onward, audiences had clearly defined expectations for Spielberg. They were anticipating wonders, which were so rarely offered by Hollywood luminaries of the time. Originally conceived as a modest television film, Spielberg’s feature debut proved the extraordinary visual and dramatic inventiveness of the creator, who, right at the beginning of his career, clearly showed that cinema was an element he could master effortlessly.