JAWS Deciphered: Behind the Scenes of Spielberg’s Hit

In 1964, American writer Peter Benchley read a newspaper article about a great white shark wreaking havoc in the coastal waters of the United States. In the early 1970s, his publisher urged him to write a book based on this event. Thus, the novel Jaws was born. Even before its release in the publishing market, the manuscript made its way to the producer duo Richard Zanuck and David Brown (The Sting), who immediately purchased the rights for adaptation.

At the same time, the two men produced a film by young, promising creator Steven Spielberg, Sugarland Express (1974). In search of material for his next film, Spielberg received a copy of Jaws through them. The then 26-year-old director noticed obvious similarities between the story described by Benchley and the script for his feature debut, Duel. In both stories, a lone hero is confronted with an irrational threat. Both tales are filled with the struggle of reason against an incomprehensible force that transcends logical understanding.

The seaside town of Amity has a new lawman. Arriving from New York, Sheriff Martin Brody is immediately confronted with the mangled body of a girl found on the beach. These are the remains of a meal that an enormous shark, measuring 7.5 meters and weighing three tons, has been invited to. However, the town authorities refuse to hear about closing the beaches for fear of losing seasonal clientele. More people go missing. Sheriff Brody, along with ichthyologist Matt Hooper and adventurous shark hunter Quint, sets out to sea to kill the beast. But after the first confrontation with the predator in open water, Brody utters the memorable line: We’re gonna need a bigger boat…

The enthusiasm with which preparations began was directly proportional to the chaos in which Jaws was created. When filming started on May 2, 1974, in Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, the water was ice-cold, while the actors and extras had to pretend it was the height of a hot summer. During the filming of the final sequence in open water, two cameras fell into the ocean (thankfully, the footage was salvaged). The first version of the script was written by Benchley himself, who then handed the reins over to Spielberg. Since the young director handled the film set much better than the typewriter, the producers brought in experienced screenwriter Howard Sackler, who completed his work but declined to have his name listed in the credits.

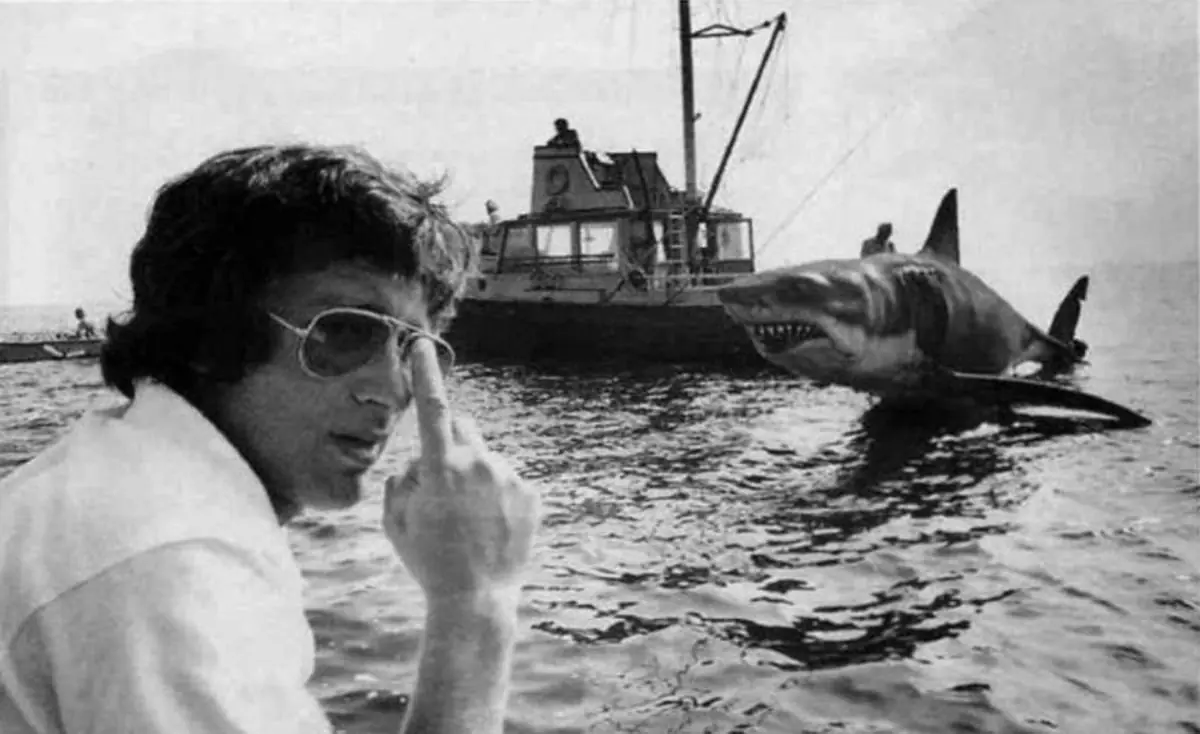

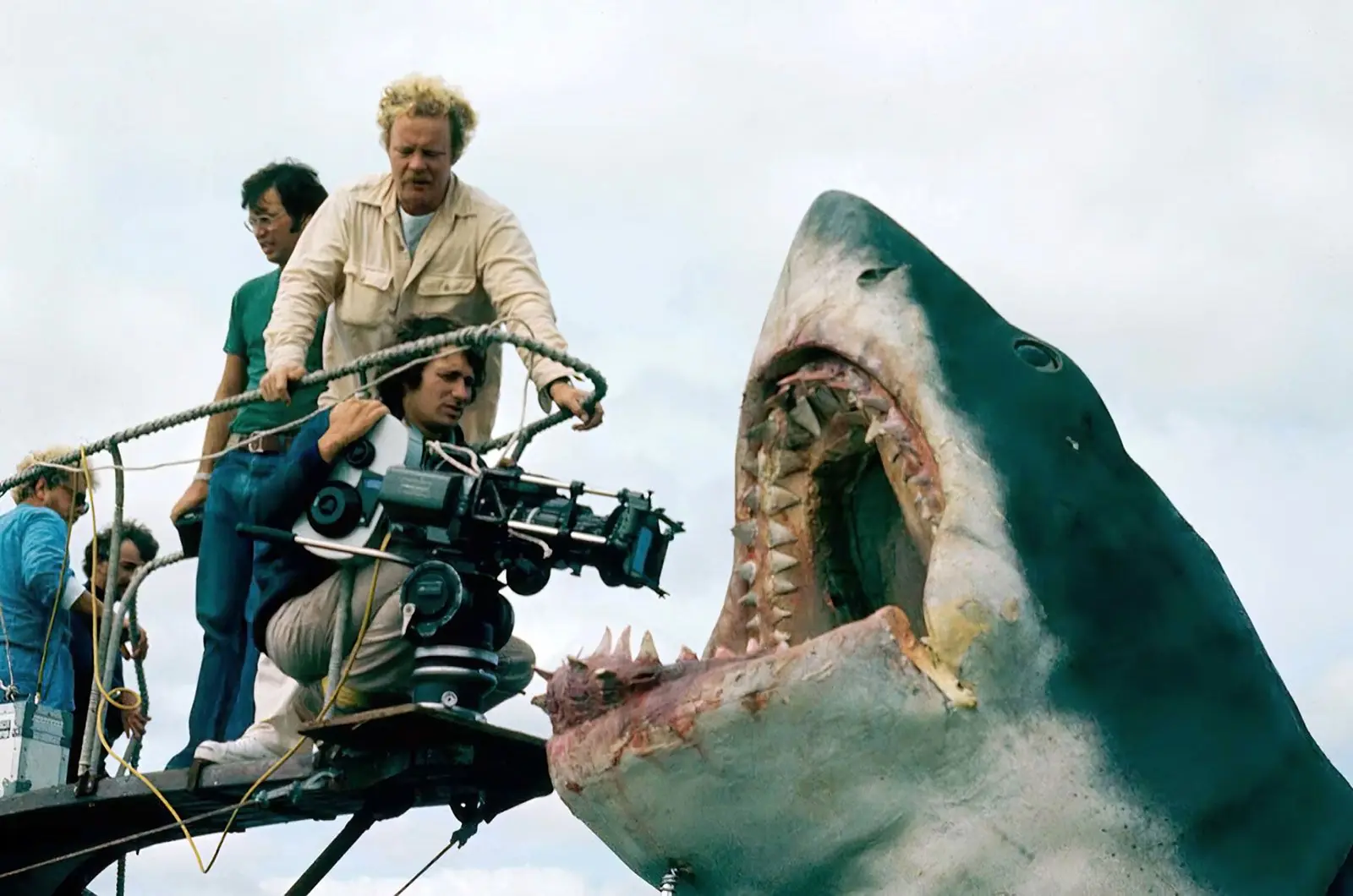

Another problem was the impending strike by the actors’ unions. To complete the planned production before the protest, another screenwriter, Carl Gottlieb, was hired, who also played a role in the film. The mechanical shark kept malfunctioning, costs were rising, union regulations complicated every aspect of production, and the actors’ strike loomed, pressuring an already delayed shooting schedule, which ballooned from the planned 52 days to 155 days. The crew struggled to manage the outdoor conditions, which had been carefully selected. The island of Martha’s Vineyard was surrounded by very shallow coastal waters (about 9 meters deep), extending 20 kilometers into the sea. This allowed for scenes with the mechanical shark to be filmed relatively easily, as its support structure simply rested on the shallow bottom. No other location on the East Coast of the USA met so many production requirements at once.

In such nightmarish conditions, one of the most famous films in cinema history was made, after which Spielberg was hailed as a genius. Even after all these years, Jaws remains an unblemished spectacle of perfectly calculated horror, finely tuned down to the last detail. Spielberg discarded everything unnecessary from Benchley’s novel (including a romantic subplot between Hooper and Brody’s wife) and retained the central theme that occupies half the film: the struggle of three men against the shark, which intentionally evokes Moby Dick.

He was aided in this by John Williams’ music, which illustrated the shark’s attacks with brilliantly simple bass strings, as well as the masterful editing by Verna Fields. Cynics even claimed that the success of Jaws was almost entirely due to Verna’s exceptional command of the art of storytelling through glue and scissors. After test screenings, Spielberg realized that the film was missing one crucial scene, one that should make the viewers’ hearts stop. So, in Verna Fields’ private pool, he shot the moment of discovering a human head inside the wreckage. Richard Dreyfuss paid for this scene with pneumonia, but it truly became one of the most memorable moments of the film.

Peter Benchley envisioned an acting dream team: Robert Redford, Paul Newman, and Steve McQueen, but ultimately the roles of Brody, Hooper, and Quint were played by other actors. Roy Scheider landed his role thanks to his appearance in The French Connection, a thrilling spectacle by William Friedkin (although the producers also considered the perennial savior of the world, Charlton Heston). When Scheider first met Spielberg, he walked in on a discussion about the scene where the giant shark crushes the boat. The actor couldn’t believe his ears that he was going to star in a film that would include such unbelievable scenes.

Richard Dreyfuss joined the cast due to his role in American Graffiti, directed by Spielberg’s friend George Lucas. Other candidates for the role of Hooper included Jeff Bridges and Timothy Bottoms. For the role of Quint, the arrogant shark hunter, Spielberg had envisioned Lee Marvin, who turned down the script. The second choice was Sterling Hayden, an actor with the face of a Yankee tough guy, known for The Killing and Dr. Strangelove by Stanley Kubrick. Since Hayden got into tax trouble, the producers suggested Robert Shaw, whom they had known since The Sting. Shaw privately disliked Dreyfuss, and their constant bickering greatly benefited the characters they played. The famous chilling scene of Quint’s story about the crew of the USS Indianapolis being devoured by sharks (a real event!) was largely devised by Sackler. However, Spielberg saw in it material for an excellent monologue, which was developed by Spielberg’s friend, later Conan the Barbarian director John Milius. The final screen version was the work of Robert Shaw, who added a few lines and electrifyingly delivered the story on camera.

Most of the full-shark shots were played by Bruce, the mechanical model constructed by Robert A. Mattey, a veteran of mechanical effects, including in the Disney adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) directed by Richard Fleischer.

In the 1970s, Mattey was already retired, but he took on Spielberg’s challenge and constructed three models (three years later, with Jaws 2, Mattey worked for the last time). The first was used for filming from the left side, the second from the right, and the third from the front. The hidden mechanisms kept jamming because Mattey did not anticipate that saltwater could be such a destructive factor. As a result, Spielberg tricked the audience with the subjective point of view of the shark, using a fin model and barrels being towed on the water’s surface. This way, the shark remained narratively present in the film despite its physical absence.

However, the script included an underwater sequence with a cage from which Hooper was supposed to kill the shark. But unlike the scenes shot above the water’s surface, there was no mechanical model involved here. The only way to show the beast in its full glory was to film a live shark in its natural habitat. For this purpose, they turned to Ron and Valerie Taylor, a couple who professionally studied shark life. Both agreed to film a live shark in the waters of southern Australia, but literary fiction stood in the way. The movie shark was supposed to be nearly 8 meters long, while the real predator reached a maximum length of 4 meters. They needed to somehow cheat the scale in shots showing the shark swimming around a person.

The problem was solved by placing the diminutive stuntman Carl Rizzo inside a cage that had been reduced by half. Only a few shots of a live shark swimming around the cage with a person made it into the film. The rest was staged in the MGM pool using a mechanical model with stuntman Richard Warlock standing in for Richard Dreyfuss. An exception was made for a few shots of the shark entangled in ropes holding the empty cage. These frames were captured almost by accident, but the footage proved to be so suggestive that Spielberg changed the script, having Hooper emerge from the cage. As a result, the film featured fantastic shots of a real shark thrashing the empty cage from which its prey had managed to escape. Ultimately, the live shark broke free from the cage, freed itself from its bonds, and swam away. For Ron Taylor, who was capturing this struggle, these were the most magnificent moments he had ever witnessed in his life, which was filled with observing underwater life.