BREAKING THE WAVES. Von Trier’s Touching Masterpiece Explained

It is such a peculiar entity, like all the work of the Dane, that it’s difficult to compare it with other representatives of the psychological drama genre (e.g., films by Ingmar Bergman or Michael Haneke).

This film takes no prisoners—you either reject it, flee, and forget it, or you perish from the bullets fired by Lars. There is no middle, safe road. There are no viewers who shrugged off Breaking the Waves. If someone claims otherwise, they either confuse the film with some other, or they depreciate von Trier‘s work on principle (because! Because Antichrist!) without intending to use their brain. It’s true, this is not an easy film to watch. It’s an unpleasant piece in both form (von Trier was still contemplating Dogme 95) and content, due to the many directorial manipulations present.

The following analysis (SPOILERS!!) was published about 13-14 years ago. Has my interpretation changed? I don’t think so, and a repeat viewing only strengthened Breaking the Waves in my personal ranking of the best films I’ve seen. It is no coincidence that it stuck in my head so firmly.

Writing about Breaking the Waves is an arduous and one of the most challenging tasks. A film that is unlike any other, emotionally the most intense, interpretable on many levels. Above all, it’s a work that doesn’t let me sleep peacefully, taking over all thoughts and feelings for a while, which instead of flying out of my head and imagination, continue to torment and unsettle me. Lars von Trier’s film is a work I can call the best cinematic creation the world of cinema has given us. For one simple reason:

Breaking the Waves draws you into a dangerous game, shocking and intimidating with the story of Saint Bess McNeill, played by the debuting Emily Watson, and… it is the most brilliant, most perfect acting role I have ever seen.

You can either hate or love von Trier’s film. This director tortures the viewer with premeditation, creating a story that is both beautiful and nightmarish—because it’s true, unusual. This disturbs, then hurts, because the parable of good Bess is not simple, infantile, and certainly not stupid (as one might hear such opinions). This film can be hurt by a brief description because it seems to be a simple love story between Bess and Jan. Lars von Trier wrapped this simplicity in garments so beautiful, yet simple—he created a story combining religious, philosophical, and sociological threads. And also bordering on a kind of moral fable, telling about good Bess, a human who probably never existed, and if someone somewhere ever met a person similar to Bess… But no, it’s impossible, unless you, dear readers, were patients of a psychiatric hospital, where those who are abnormal and different, claiming to be Christ, Mary Magdalene, and Joan of Arc in one person, end up. Expelled from collective consciousness, from our culture, which in no way craves and rewards pure goodness. That is Bess.

About her at the end.

The Love Story of Bess and Jan

(Roxy Music All the Way From Memphis) First, we see a wedding, unshaken happiness, which is everything the overly sensitive heroine needs to live. (T-Rex Hot love) First sexual experiences, delight in physicality, discovering the secrets of love. Happiness does not last long. Bess’s husband works on an offshore drilling rig, so he has to leave for a few weeks. (Deep Purple Child in Time) Bess suffers from separation. The separation from her beloved for someone so sensitive is nothing but a painful experience… Daily waiting for a phone call, any sign from her beloved.

(Procol Harum A Whiter Shade of Pale) Jan has an accident on the platform. His entire body, from the neck down, is paralyzed. Doctors give little hope for survival. However, Bess urges the doctors to save Jan at all costs. They succeed, and although completely paralyzed, her husband can return home. For Bess, this is the fullness of happiness, because her beloved is right next to her. After a failed suicide attempt, Jan asks Bess for an extraordinary thing—she is to meet other men and sleep with them, and then tell her husband about it. Of course, the girl does not agree to such a perverse game. (Leonard Cohen Suzanne) Jan’s condition worsens, and Bess sacrifices herself for her love, especially since with each sexual sin, Jan’s health improves. (Elton John Goodbye Yellow Brick Road). Bess is expelled from the local community because such behavior is not in line with the existing laws and religious norms. Her family and friends turn away from her. (Thin Lizzy Whiskey in the Jar) However, love is the most important thing and it demands the greatest sacrifices. Bess wants to save Jan by offering herself as a sacrifice…

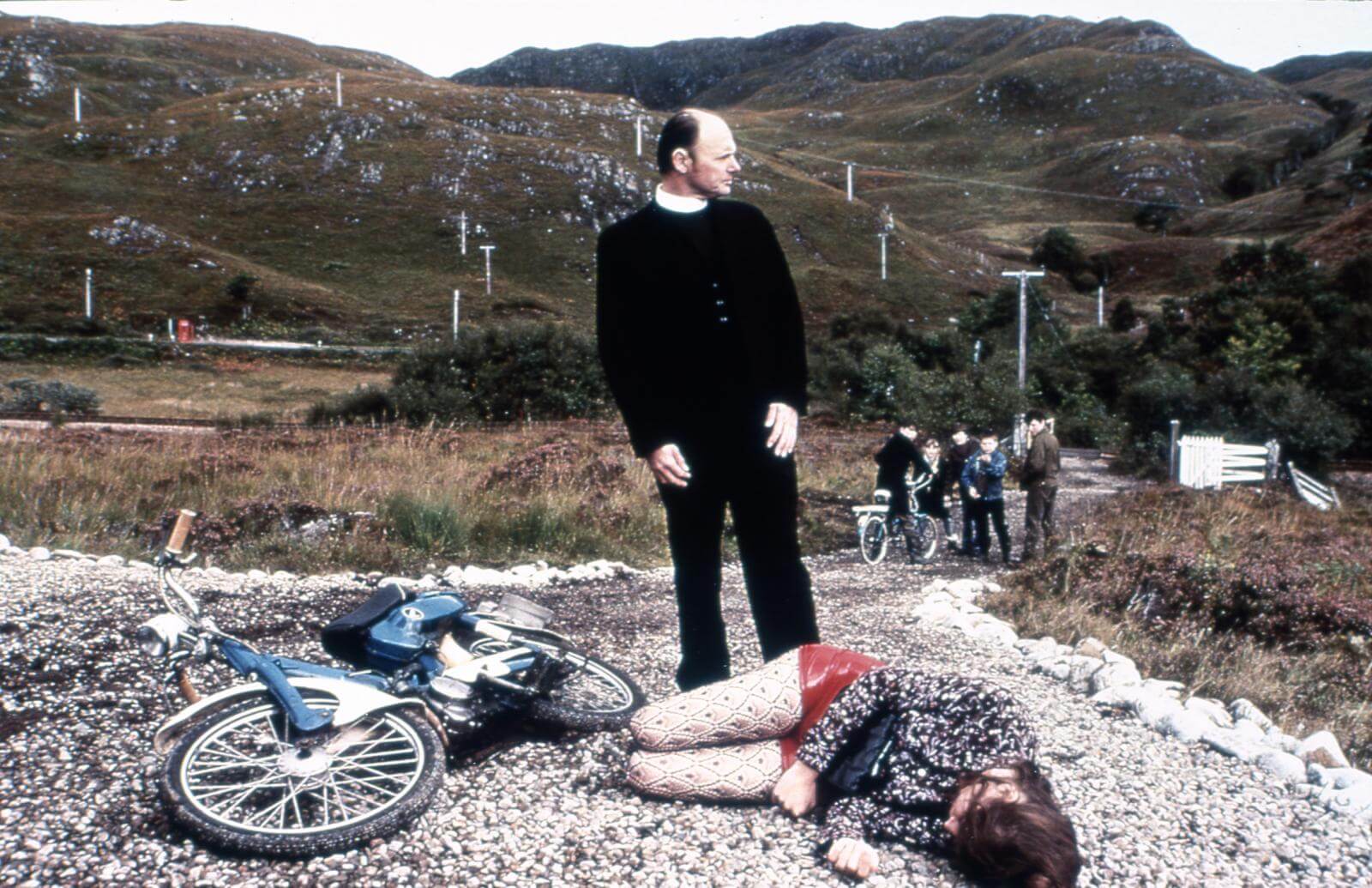

Place

Bess breaks the waves somewhere in the north of Scotland, in a desolate, lost place. It’s cold, windy, misty. Everyone is hidden behind brown garments, without a smile, without regret, without hatred, without any signs of any feelings. They go to a funeral. Women stop halfway, men carrying the coffin go further, towards the freshly dug grave. Women avert their eyes, pray alone asking God for forgiveness for their excessive curiosity. Men—focused, silent—pray over the coffin remembering the deceased. God answers them that the soul of the deceased will not reach Heaven, but will head towards Hell because the sin that choked both body and soul of the person who lived yesterday will never be erased…

Life

The local community is a closed enclave surrounded by a wall of mountains and natural emptiness. The church is the central place for social meetings, and the pastor is the guide on every road, from life to death. Their world is religion, here the most conservative form of Protestantism. The presence of clearly defined village boundaries determines the existence of a kind of faith not free from stereotypes, simplifications, schemes. Such small, closed groups want to remain so for as long as possible, protecting tradition, culture, and religion from the Evil (that is, different, not fitting into the familiar reality), breaking any signs of insubordination and anti-traditionalism.

The life of the inhabitants is filled with the spirit of Protestant puritanism. The main point is that God rewards with the Kingdom of Heaven those who dedicate their lives to one thing—work. Work that will certainly give salvation, which is to be the only and most important goal of a person faithful to God. Puritanism is a form of access to the cave of the unconscious through questions and answers about daily work, which is asceticism, sacrifice, dying—then rebirth follows, God gives the answer… And then a return to the same tedious work as a remedy against the danger of too close, too intimate an approach to the sacred. Thanks to extraordinary efforts, the Puritans managed to find in the Bible a model of balancing asceticism and revelation, practicality and spirituality, responsibility to the Creator, who made them the New Chosen Nation, to whom He gave the Earth to rule, who will certainly achieve salvation… Asceticism encompasses human existence, his ability to feel hatred or love. No one has the right to oppose the harsh cultural-religious rules, no one can rebel, and if someone different is found, creating different laws only for themselves—they are excluded from the community, forever marked with the stigma of a faith traitor. Then even a mother and father will not open the door for their daughter, then they will not even come to the funeral of their child…

Life in Bess McNeill’s world seems utterly nightmarish. However, judging religion and culture might lead viewers down a path of inherent intolerance. Bess’s world is real; it exists and forms the basis of American or Scandinavian culture (though in a less conservative form). One must forget any presumed oddity or abnormality of the place and its people. This world is not translatable; it is not compatible with our values, habits, or delusions. But it is an incredibly real, tangible world.

Jan and Dodo

Jan is the most important character.

The initial impression viewers get of Jan can be described as repulsion. He cruelly torments Bess, perversely wounding her feelings and innocence. He tortures her with his sick visions, demanding a moral violation. But is Jan’s behavior truly unacceptable, and is he mentally ill? Completely paralyzed, he can only move his mouth, which is difficult for him. Accepting the harsh reality of a life that can hardly be called a life is too challenging. Such suffering is unbearable, unimaginable. Jan lives thanks to Bess, who naively saves him by not allowing the doctors to disconnect him from life support. He loves good Bess sincerely, but why did she decide to prolong his suffering, not allowing him to die? Death would have been a release from earthly, painful, and meaningless existence in suspension.

Maybe Bess will say “enough,” stop loving him, and when she’s no longer with him, they will let him die. By forcing Bess to be with other men and signing the petition to commit Bess to a psychiatric hospital, he thinks of himself and his own death, which he can never achieve as long as he’s dependent on his wife’s will and her constant presence. Love is beautiful but it enslaves, consuming the oxygen needed for life/death. Jan just wants to die. Let that be his justification.

Dodo, Bess’s cousin. Calculating, conforming to the dictates of the community in which she lives. However, there is an understanding in her eyes for the attitudes of Bess and Jan. She lost her husband and to find appropriate peace and maintain balance, she moves from the city to the village, taking Bess under her care. Her gaze towards Bess is full of simple understanding, though her words and gestures suggest a certain distance from her younger cousin. This coldness and aloofness are only superficial. Dodo’s character is fascinating because behind the facade of a typical Puritan lies a mirror image of Bess. The feelings Dodo experiences when Bess dies, her terrifying scream, despair, and later breaking the rules, breaking the waves… Perhaps Bess would have become a woman similar to Dodo if her sacrifice had not taken such an extremely good form. She would have had to hide in the conventions of the community for the rest of her life, like Dodo.

Bess

Her prayer. She talks to God, asks Him questions, and God answers. Every prayer of every person seems to have something of schizophrenia. The mind splits into two parts – the one asking, apologizing, and the one being God, dwelling in the imagination, shaping the ideal of God. This Idea advises, warns, gives advice, commands, prohibits. Bess, having a conversation with Him, is not an unstable lunatic but a normal person who, while praying, is only talking to God. Only?

Her eyes. They avoid the gaze of others. Always downcast, but cheerful, mischievous, curious about the world, and full of wonder. When Bess experiences her first sexual encounter, we only see her eyes, her astonished gaze. For a moment she closes her eyelids and smiles.

Her naivety in words, gestures, and surprised looks at what she sees. Bess, like a child, sulks, pouts, cries for a moment, and then jumps with joy. When she is sad, she naively believes that shouting will help; when she is desperate, she just needs to fall asleep and forget everything; when she is angry, she makes a stern face and stomps her foot nervously. Bess’s simplicity makes her Good. Yes, with a capital G. Good. And if someone is simply (or maybe extraordinarily) just Good, they are an innocent, silly child who is just learning about the world, its rules, norms, and customs. Bess loves Jan with a complete love, which poets have written about as the true, singular love that gives wings and lifts you up. It is the love of a young child, dependent, trusting unconditionally and uncritically in their guardian.

Bess’s feelings are pure, filling every smallest part of her being. Love, longing, anger, and ultimately sacrifice permeate her completely, always and everywhere. If to love, then to the end, and not just occasionally, unnoticeably passing by one’s own feelings. If to suffer, then to sob alone, howl at the stars. If to feel sadness, then to let the gloomy rain fully penetrate. These are emotional extremes.

Her sacrifice. It is said to be a trait of saints – to be Good to the end, to death. Naively, with childlike simplicity, but consciously, to plan a world that cannot survive without sacrifice. This requires faith in the sense of doing anything – the belief that the world is worth changing; that it is improper to look only at oneself, at one’s own problems, surrounding oneself with an unbreakable wall. This is a deeply religious stance, as it references the very figure of Jesus Christ. Sacrifice, for which the reward will be eternal salvation.

Bess’s path is similar to the Way of the Cross that Jesus walked two thousand years ago. In the fate of these humanly Good beings, there is voluntary self-offering for others, and this stance encounters numerous difficulties – those who do not understand Good threw stones and made them carry the cross on their shoulders. Those who do not believe in the Goodness of Bess closed their homes to her, excluded her from the local community. Bess’s crown of thorns is the mask of a whore she must wear to save Jan; her scourging – the cruelties committed by dirty sailors on the ship. Stones thrown by recent friends are to be a punishment for the sin, which is Goodness. Bess’s cross is this sacrifice. On the Scottish Golgotha, right under the cross, stands her mother.

Finally, salvation, which was meant to give suffering a meaning. And such a meaning exists because it provided a semblance of something divine, something supernatural, miraculous. Jan recovers – he is saved by Bess. And for her, for her goodness, for her childlike naivety… bells ring in heaven. One of the last scenes shows a turbulent stream. Just beyond the bridge, the rushing torrent turns into a calm, gentle river.

On earth, Bess was a whore; in heaven, she is a queen.