BARRY LYNDON Unveiled: A Masterpiece from a Bygone Era

When she chooses an officer over him, Barry kills the man in a duel and flees, eventually joining both the British and Prussian armies, fighting on the fronts of the Seven Years’ War. After meeting his fellow countryman, Chevalier de Balibari, Barry deserts the army. Living as a gambler and a rogue, he encounters the wealthy Lady Lyndon, seduces her, and, following her husband’s death, marries her.

Barry Lyndon begins like a Monty Python sketch. A voiceover informs us that Redmond Barry’s father might have had a long and successful life, but things turned out a little differently… and at that moment, a gunshot rings out. One of two duelists collapses onto a lush green meadow. Just like that. The strict, almost absurd adherence to the norms of the honor code in the buttoned-up world of 18th-century British conventions became for Stanley Kubrick another laboratory for dissecting societal structures. Humanity—whether in wartime trenches, en route to Jupiter, or amidst the moral decay of a dystopian future—always remains a prisoner of invisible fortresses. At best, one might embark on a long and exhausting struggle, but it will be a battle marked by defeat from the very beginning.

Choosing the novel The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq, written in 1844 by the renowned British author William Makepeace Thackeray (Kubrick initially considered adapting Vanity Fair, the writer’s most famous novel), seemingly placed Kubrick in new territory: a costume drama set in the 18th century. However, the director once remarked that psychological novels are the best material for films, as they provide pre-crafted internal character profiles, allowing the filmmaker to focus on crafting a sufficiently captivating plot. Barry Lyndon is another example of Kubrick’s creative appropriation of someone else’s world to play his own game of chess (a similar approach was taken with The Shining, for which, as we know, Stephen King lashed out at Kubrick—not to offer him a hug, to say the least).

Redmond Barry, rechristened Barry Lyndon, is yet another Kubrickian outsider trapped in an unbearably formalized world. Another red stain disrupting pristine white—though in this case, the white is replaced by green. Kubrick illustrates this literally in several scenes, such as on the lake, where the tranquil tones of nature are interrupted by the sharp red of a large sail, or on the battlefield.

The world surrounding Barry resembles a grotesque theater filled with human marionettes. The formalized stiffness of British society, under which improper passions simmer, and a life lived according to hypocritical rules deemed sacred, is observed here with a solemnity that far exceeds the boundaries of common sense. Even the battlefield confrontation with French troops resembles a ritualized parade—one all the more poignant and senseless because it is carried out under relentless gunfire, mercilessly mowing down row after row of soldiers obediently marching to their slaughter. Only Barry displays a human gesture, carrying his commander off the battlefield (practically the same thing Forrest Gump did for Lt. Dan). And yet, there’s something irresistibly fascinating about it all. Barry’s robbery in the forest by two highwaymen is, on the verbal level, an eloquent duel of courtesies. The pistol duels or dialogic exchanges of contested matters, stripped of their narrative context, could resemble a refined conversation between the two esteemed professors.

Stanley Kubrick was always captivated by the language of his characters and the limits of verbalizing emotions they could reach. His characteristic irony, emphasizing the absurdity of the depicted world, is unmistakable. In Dr. Strangelove, the military language of the dialogues stood in clear opposition to their meaning. Here, that role is partly taken over by the nameless narrator, whose dry, chronicle-like commentary often clashes with the solemn gravitas of the rituals that fill the characters’ lives (in the novel, Barry himself was the narrator). For example, in the aforementioned battle scene, before the first shot is fired, the narrator dispassionately informs the audience that this skirmish was not even noted in history books. Bodies fall in heaps, yet one cannot help but feel that these soldiers were already dead in life. Much like the entire world they inhabit, against which Barry’s activity—his resourcefulness, succumbing to feelings, emotions, desires, moods, and fleeting moments, leading him astray though they may be—stands as a glorious affirmation of humanity amidst a perfectly arranged wax museum.

There are a few period films in the history of cinema that feel like authentic visual records, captured on location during the events they depict, in times when the invention of the film camera was beyond the imagination of even the greatest visionaries. Such was The Elephant Man by David Lynch (1980), and five years earlier, there was Barry Lyndon. This film is considered one of the most visually stunning works of all time. Some dislike the term “picture” when referring to moving images, but in the case of Barry Lyndon, the word takes on a very literal meaning.

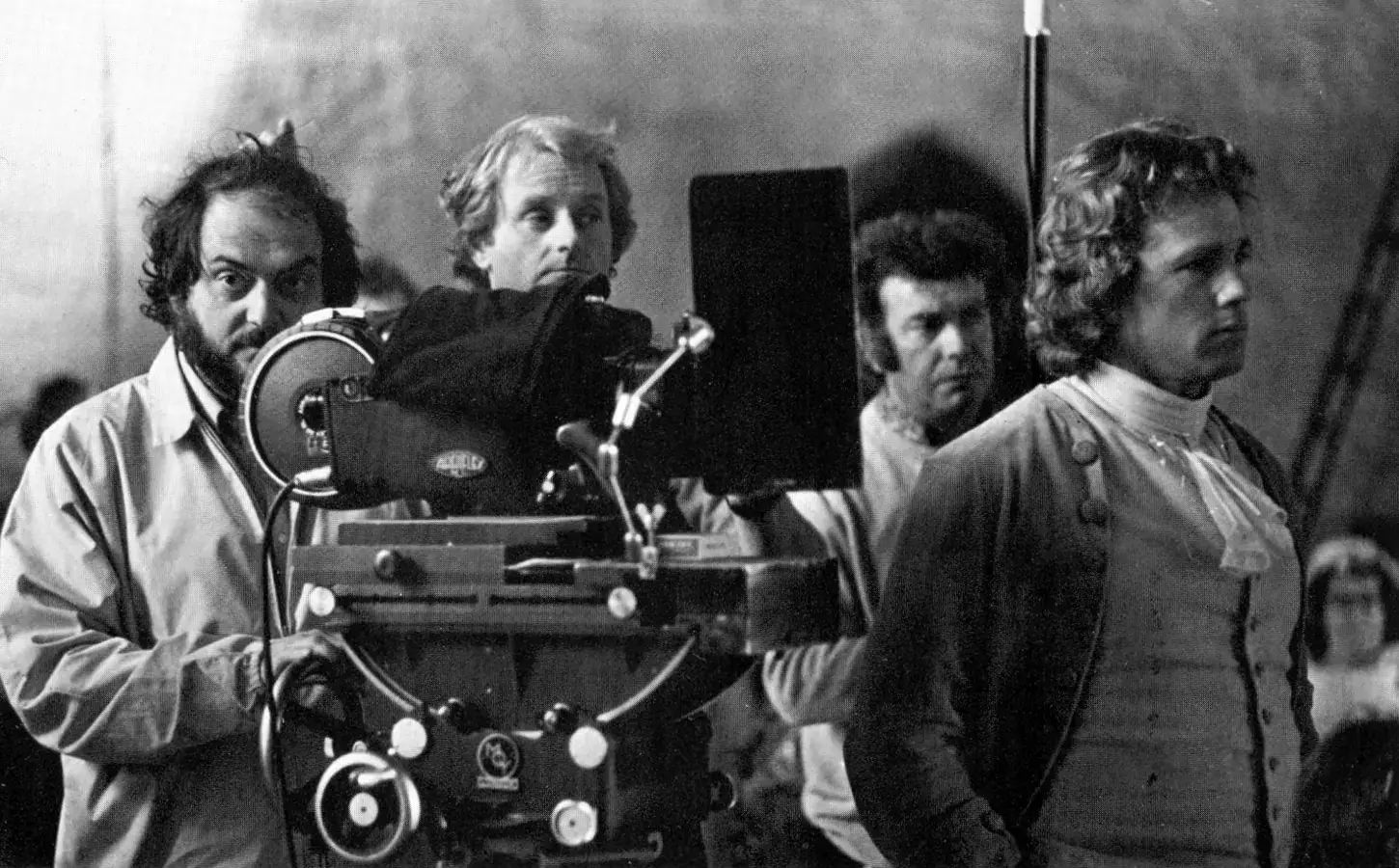

Every frame of this masterpiece is a finished painting, crafted with natural light and framed within the cinematic composition devised by Stanley Kubrick and cinematographer John Alcott. The Irish, German, and English landscapes are so breathtakingly beautiful, so crystal-clear, that one might suspect the use of matte-painting techniques (where parts of the frame are replaced with painted additions on glass). But that’s not the case! Capturing such sharp and pristine vistas, stretching to the horizon under the lazy drift of picturesque cumulus clouds, amidst the capricious island weather, seems nothing short of miraculous. The explanation for this miracle is relatively simple: filming lasted two years. The visual artistry is awe-inspiring, particularly as Kubrick and Alcott succeeded in the aforementioned complete reconstruction of the era.

The film was shot entirely in natural settings, with interior scenes filmed in actual historical locations. Not a single shot was taken on a soundstage. Costume designer Milena Canonero dressed the actors in authentic, often extravagantly detailed period clothing. Whatever could not be purchased or borrowed from museums and collectors was meticulously recreated with extraordinary precision and fidelity to the originals.

The lighting in Barry Lyndon has been the subject of countless articles and an endless number of online discussions. This is particularly remarkable given that cinematographers themselves often speak with a touch of irony about the sparse, and usually cheap, compliments offered by critics—whether major or minor—limited to superficial remarks about “beautiful cinematography” (often in the context of cliché sunsets or flashy camera movements). Against this backdrop, the visual aspect of Kubrick’s film shines with the rare brilliance of well-deserved and expertly analyzed acclaim.

The work of a cinematographer is primarily about mastering light, which is most often artificially produced. Filming on location is a gamble, a roulette between art and weather. Barry Lyndon is an unprecedented portrayal of a world lit solely by the Sun during the day and by candlelight dispelling the darkness of the night. In daytime scenes, John Alcott used artificial lighting in a way so subtle it became imperceptible. In situations where natural light posed challenges to the filmmakers—clouds, rapidly fading twilight—the cinematographer meticulously recreated natural illumination using his own lighting equipment.

The famed nighttime scenes, with actors performing solely by candlelight, have become as legendary as the film itself. Kubrick, in his obsessive pursuit of perfection, ruled out the use of artificial lighting. As an authority on photography, he examined Zeiss lenses originally designed for still cameras used by NASA during the Apollo missions. These were the fastest lenses known at the time (allowing for the quickest exposure of negatives in minimal light, or in other words, enabling maximum aperture), and only such lenses could provide the necessary brightness and contrast for filming by candlelight.

The problem was that these lenses, designed for still photography, could not be mounted on Mitchell BNC film cameras (all other shots in the film were captured using the Arriflex 35BL camera, which Alcott also used for The Shining). Ed DiGiulio, the director of Cinema Products Corporation, personally solved the issue with a complex custom adaptation system.

Another challenge was the Mitchell camera’s viewfinder, through which scenes lit solely by candlelight were barely visible to the operator. To address this, they used a viewfinder salvaged from an old Technicolor camera used for early color films. These scenes were shot with an f/0.7 aperture—the widest ever used in a feature film. At such low light levels, depth of field was virtually nonexistent, and focus had to be set to the millimeter using a video assist system attached to the camera.

This explains why the actors in the “candlelight” scenes made no sudden movements and barely shifted their positions. Adjusting focus for a moving actor was practically impossible in such dim lighting. Interestingly, this technical limitation perfectly complemented the film’s overall atmosphere, as Kubrick’s relentless scrutiny of British stoicism blended seamlessly with the enforced stillness of candlelit settings. Ironically, it was only after the film’s completion that film labs began producing negatives capable of proper exposure in such low-light conditions, eliminating the need for tricks with ultra-fast lenses.

Another unconventional cinematographic technique, rarely seen in period films, was the repeated use of zoom-outs, almost like a mantra. Each began with a close-up of a detail crucial to the scene, only to pull back over several seconds, transforming all those details into mere, insignificant elements within a magnificently composed wide shot. It’s as if, through this simple cinematographic maneuver, Kubrick was trying to say that all human follies are inherently so small and insignificant that a slight shift in perspective—an ability to take a broader view of the majestic Irish hills—renders humanity’s concerns utterly trivial. This godlike perspective had already been explored in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick’s gaze on the 18th century similarly leaves no illusions about his view of the human condition. With his demiurgic obsession, Kubrick could, through a single shot or even an editing cut, distill complex philosophical ideas into cinematic clarity.

Kubrick took his mastery of classical music in film to a new height in Barry Lyndon, reaching what could only be called mega-perfection, if such a term may be allowed. The brilliant imagery-driven narrative gained an extraordinary rhythm through the use of classical compositions, selected with incredible care, taste, and elegance. The result—something film composers strive to achieve by creating original music to fit pre-filmed scenes—was accomplished by Kubrick with pre-existing pieces, originally written under circumstances entirely unrelated to the film. Through precise synchronization of the visuals to the rhythm and thematic anchor of the music, Kubrick achieved complete harmony between meaning-saturated images and the desired tempo and mood of the story. It’s astonishing. The scores feel as if they were composed specifically for the scenes they accompany, such as the duel between Barry and his stepson, Lord Bullingdon—a sequence realized with Hitchcockian suspense and edited over 42 days. The nerve-wracking, slow-paced duel—more a clash of personalities than pistols—was underscored by a deeply bass-heavy rendition of a recurring theme by George Frideric Handel, enhanced by string counterpoints.

On the other hand, the exquisite use of the traditional Irish melody Women of Ireland, performed by The Chieftains, is equally breathtaking. Despite initial skepticism about the length of this three-hour period drama, Barry Lyndon captivates viewers, who watch it with bated breath.

In terms of genre, the absolute brilliance of Barry Lyndon was perhaps only matched by Milos Forman’s Amadeus. However, contemporary audiences were not particularly enthusiastic about Kubrick’s film. While Barry Lyndon was recognized by the Academy with Oscars for Cinematography (John Alcott), Art Direction (Ken Adam, Roy Walker, and Vernon Dixon), Costume Design (Milena Canonero and Ulla-Britt Söderlund), and Leonard Rosenman’s adaptation of the music, it was Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest that swept the major categories, winning Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay—categories for which Kubrick had also been nominated.

Kubrick invested the film’s $11 million budget in a style of cinema that was already falling out of favor, displaced by modern thrillers, horror films, and disaster movies. A bad omen for the production was the two-year filming schedule, which had to be paused twice due to escalating costs. This marked the beginning of the blockbuster era dominated by the likes of Spielberg, leaving little room for such sophisticated auteur cinema, no matter how masterfully shot and narrated. Kubrick acknowledged this shift…

Adrian Szczypiński