ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST. Forman’s Masterpiece Explained

The nearest town to its slopes is more than thirty kilometers away. Other prominent peaks, once called Faith, Hope, and Charity by early settlers, are also distant from the mountain. Bachelor owes its name to this separation, standing apart from the powerful cluster of three volcanoes located to the north of its slopes. We might call it the Bachelor shyly gazing toward the chain of the Three Sisters, which consists of the aforementioned Faith, Hope, and Charity.

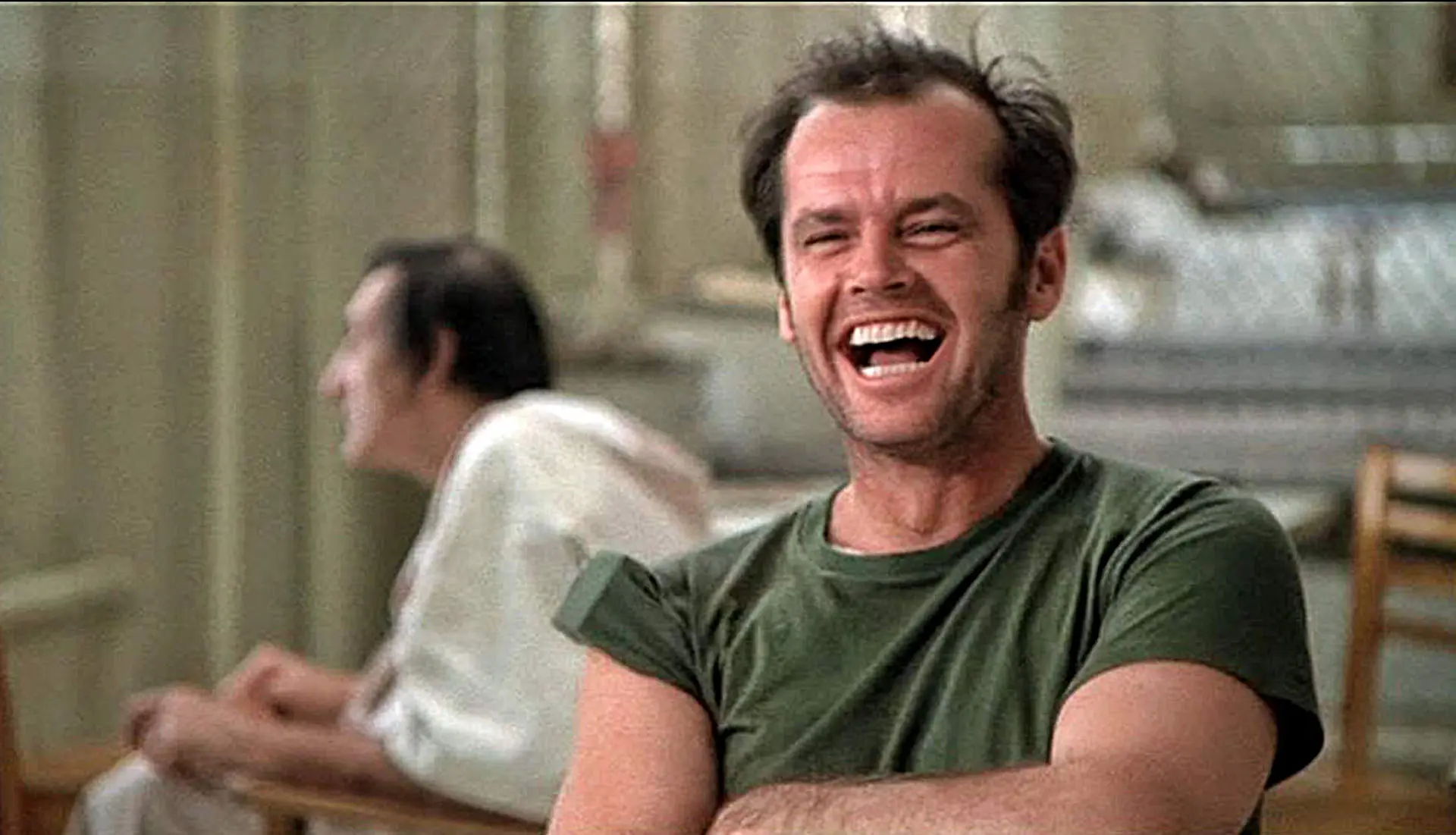

In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, there is little room for coincidence. Writing about the film, Jerzy Płażewski points to Milos Forman‘s daring attention to detail, a skill honed during his time in the Prague school, also known as the Czechoslovak New Wave. When, after a moment of on-screen silence, the viewer begins to hear Jack Nitzsche’s musical theme played on a saw and wine glasses, and the snowy peak of Mount Bachelor comes into view, we realize Płażewski was right. The opening scene of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is also its visual summary. A solitary mountain rising amid countless nearly identical trees and dozens of similar lakes could easily be renamed from Mount Bachelor to Mount McMurphy. It’s a bit odd, lonely, but also, in a certain way, beautiful—just like the film’s protagonist and Nitzsche’s unforgettable music theme.

Havana Lights

Ken Kesey was born in September 1935, in the small village of La Junta, Colorado. However, at the age of eleven, his family moved to Springfield, Oregon. These areas became his home and had the greatest impact on the author’s work, who humorously claimed he was too young to be a beatnik and too old to be a hippie. Kesey’s self-deprecating remark reveals much more than just his tendency to joke about himself. He was truly a product of his times, witnessing the rise of beatniks and the emergence of hippies, who quickly began repeating the mistakes of their spiritual predecessors. As an intellectual shaped during an era of turbulence both within American borders and on distant eastern fronts, Kesey, like all representatives of his generation, valued freedom above all else, which in troubled times often seemed like nothing more than a dream. Perhaps that’s why his debut novel inspired “one of the most beautiful odes to freedom ever seen on screen” (Płażewski, Historia filmu, p. 438).

It’s hard to believe, but Kesey began working on the book during a creative writing course, which he attended after achieving success in earlier stages of education. Among his accomplishments was winning the prestigious Harper-Saxton Prize, awarded to authors working on their first novel (Kesey presented a manuscript that was never published). At Stanford University, his mentor was Malcolm Cowley, a recognizable figure in the American literary scene, who personally knew writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, the latter of whom Cowley held in particularly high regard.

By chance, while not entirely satisfied with his linguistic studies, Kesey began attending a literary seminar. The class was led by James B. Hall, an experienced academic and author, who quickly realized he was dealing with a talented writer. Before working under Hall, Kesey primarily read science fiction. However, Hall steered him toward genres closer to reality. One of the first authors recommended by the instructor was none other than the newly crowned Nobel laureate, Ernest Hemingway, who in 1952 published one of the most famous short stories in literary history. When the shining lights of Havana faded from the old fisherman Santiago’s view and the giant marlin dragged his small boat into the depths of the Atlantic, the man began to reflect on his fate. One thought stood out above all others, instantly becoming his life’s credo: “A man is not made for defeat. He can be destroyed but not defeated.” Right, McMurphy?

American Horror Story

Do you remember the scene where the young psychiatrist asks McMurphy about the meaning of the saying, “A rolling stone gathers no moss”? The actor playing that role, like the hospital’s head, were real employees of Oregon State Hospital, the location where most of the filming for Forman’s movie took place. In the early 1980s, a young man was murdered on the job by one of his patients, and that was just the tip of the iceberg, leading to the hospital’s eventual closure.

Throughout its more than century-long existence, the facility frequently experienced neglect, resulting in patient suicides or deaths due to poisoning or exhaustion. In 1942, one of the kitchen workers mistook rat poison for powdered milk. Shortly after the evening meal, forty hospital patients died, and nearly five hundred suffered severe food poisoning. The postwar history of the institution is rife with accusations of rape, including sexual abuse of minors. A former Oregon State Hospital employee bluntly stated that the poorly protected building, with many nooks hidden from the eyes of cameras, was a paradise for pedophiles. Over time, cases of individual, mysterious deaths became the hospital’s specialty. Given its profile and the fact that about two-thirds of its patients were criminals, often of the highest caliber, many cases were carefully swept under the rug. Eventually, however, the rug ran out of space. A series of articles about the neglect surrounding the hospital’s cemetery earned a Pulitzer Prize. Journalistic investigation revealed that about fifteen hundred people had disappeared within the hospital’s walls, their fates and identities now nearly impossible to trace. Add to this more than three thousand corroded urns, which sat in the hospital’s basement for years awaiting a dignified burial, and you’ll quickly realize that the hell in Forman’s film may not compare to Oregon’s reality.

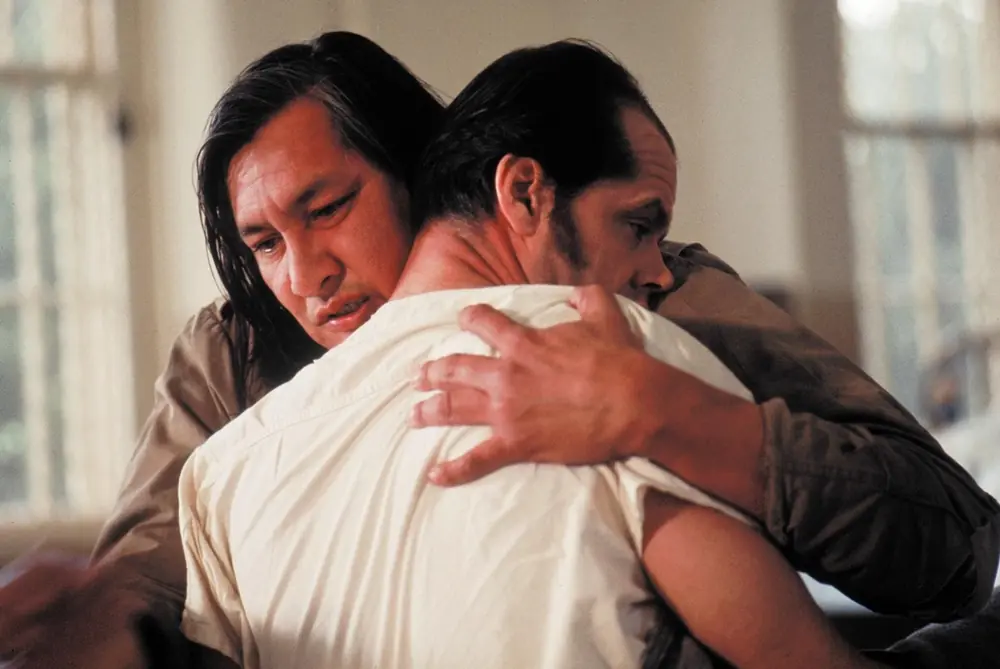

The masses of nameless patients, forever lost among the ruins of the hospital that was eventually razed to the ground, serve as a fitting metaphor for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In Nurse Ratched’s ward, any hint of individuality was snuffed out from the start. Repeated mantras and the administration of medication were designed to turn individuals into a homogeneous mass—patients whose only duty and privilege was to participate in the grotesque dance led by the head nurse. That’s why McMurphy’s behavior, and perhaps even more so Chief Bromden’s final act, is so moving and important. When the towering Native American, who for years had silently wandered the ward, defeated, with his broom in hand, resigned to isolation from the world, grabs a sink and uses it to break his way to freedom, the machine is destroyed. The Chief still remains silent, but his act becomes a powerful scream, proclaiming that he exists, that he has strength, and that he doesn’t have to participate in the festival of oblivion taking place within the hospital walls. Escaping into the forest, Bromden stops being a patient and becomes a man once more.

Creative Madness

The success of Ken Kesey’s novel quickly led to its adaptation into another medium. Just one year after the literary triumph, Dale Wasserman’s musical, which was a hit, appeared on Broadway. McMurphy was played by none other than Kirk Douglas himself, who was a major star at the time. After the theatrical premiere of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the actor acquired the rights to produce a film version. However, for years he struggled to find producers willing to fund the project. The problem was finally resolved by his son, Michael, who, in collaboration with Saul Zaentz, managed to raise three million dollars, which was sufficient to produce the film at the time.

The film’s director was chosen by Kirk Douglas. From the start, it was meant to be Miloš Forman, though for a long time Forman believed that the American star was playing a joke on him by not keeping his promises. The source of the misunderstanding was a missing copy of Kesey’s novel that was supposed to reach Forman straight from a bookstore in America. However, given that Czechoslovak authorities didn’t trust Americans, the suspicious package got stuck in one of the customs offices. The missing delivery led Forman to give up on further contact with Douglas, who interpreted this as an insult from the director. Once again, Michael stepped in and years later explained the situation, convincing Forman to take on the challenge of directing the film. The Czech director, who was just beginning his career in the U.S., agreed to Michael’s proposal, and as it turned out, this became his gateway to an international career.

However, the problems didn’t end there. Kirk, who had dreamed of playing McMurphy after his Broadway role, had become too old by 1975 to take on the part. After speaking with Forman, Douglas suggested that four younger actors could take his place. His favorite was Burt Reynolds, while other options considered were Marlon Brando, Gene Hackman, and Steve McQueen. Nicholson was chosen by the studio, which wanted to capitalize on his growing popularity. Between 1969 and 1975, Nicholson had appeared in Easy Rider, Carnal Knowledge, The Last Detail, The Passenger, and Chinatown. A streak like that couldn’t go unnoticed.

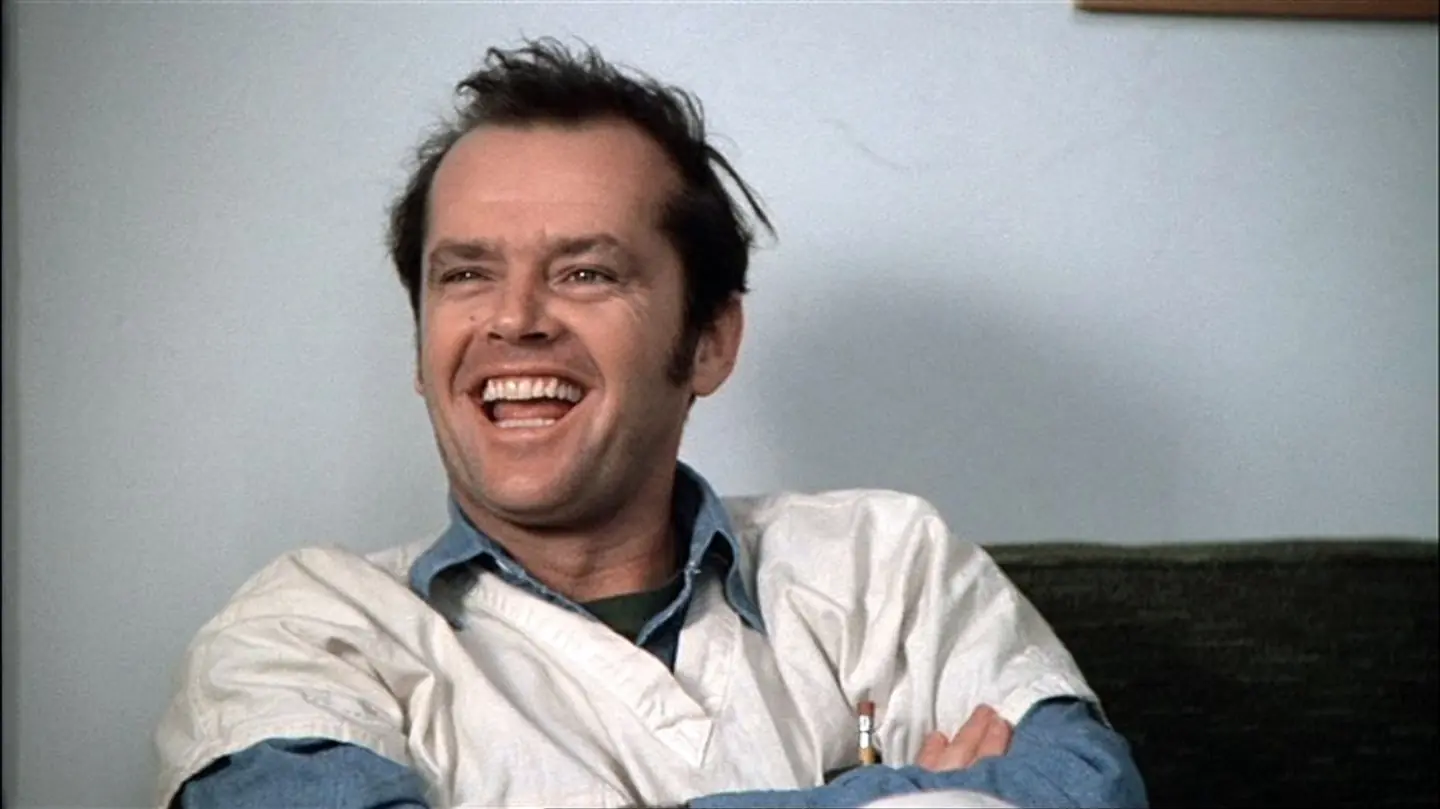

The relationship between Nicholson and Forman didn’t start off well. Nicholson was a fan of Kesey’s novel and had strong opinions about how his character should be portrayed. Forman wanted to tell the story more bluntly, placing McMurphy among characters with severe mental disorders. Nicholson disagreed, claiming that confronting his character with those who had definitively lost their minds would be pointless. He argued that McMurphy needed to interact with people capable of engaging in conscious interaction. For a long time, neither man was willing to compromise. Eventually, Nicholson’s vision won out, but this didn’t improve their relationship. Nicholson communicated with Forman through the film’s cinematographer, Bill Butler, for the remainder of the production, only pretending to be friends with the director for promotional purposes.

Louise Fletcher also successfully imposed her vision of her character. Originally, Nurse Ratched was meant to be pure evil, a slightly exaggerated figure devoid of any ambiguity. Fletcher insisted on making her character’s intentions less clear. Forman agreed, contributing to the creation of one of the most terrifying characters in cinematic history. Ratched’s inhumanity doesn’t stem from overt cruelty. Her true motives remain enigmatic, and it’s the mystery of what goes on in her mind that is so terrifying. Reportedly, most of the people on set were afraid of Louise Fletcher. To break free from the image of her character, she paraded around the set naked. When asked about this anecdote years after the film’s release, she said that she wanted to show that she was a normal woman and not an embodiment of evil trapped in a nurse’s uniform.

Such antics were a breath of fresh air on set, offering a temporary return to normalcy. The conflict between Forman and Nicholson wasn’t beneficial to the rest of the crew. The actors’ mental health was also strained by staying on the grounds of Oregon State Hospital. The main actors frequently interacted with individuals suffering from severe emotional and mental disorders. It’s important to remember that many of the patients were criminals serving their sentences in the hospital. Combined with the facility’s poor reputation and noticeable security lapses, the long stay on the ward likely caused sleepless nights for many.

During filming, the actors had the opportunity to interact with the specialists working on the ward they occupied. To cope with the challenges of working on set, Danny DeVito created an imaginary friend with whom he would talk before going to sleep. Concerned about his behavior, DeVito consulted Dean R. Brooks (who played the role of Dr. Spivey and was a longtime superintendent of Oregon State Hospital). The psychiatrist assured him that as long as the friend remained purely imaginary, DeVito’s interactions were perfectly normal. However, Sydney Lassick, who played Charlie Cheswick, did not handle the emotional stress of filming well. His work on set led to a severe nervous breakdown, prompting the team’s doctors to intervene.

It was all worth it. Just as enduring the criticism from Kesey and the battle for the final version was worth it. The author of the novel swore until the end of his life that he had never seen the film because he was furious about the removal of Chief Bromden as the narrator. There’s an anecdote, however, supposedly told by one of his friends. According to the story, Kesey once came across One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest while channel surfing and was fascinated by it until he realized what he was watching. As for the final version, 20th Century Fox wanted to force the producers to change the ending. The studio wanted McMurphy’s fate to take a different turn. Douglas and Zaentz refused. In the end, United Artists distributed the film. Winning the Oscar “big five,” meaning victories in the five main categories at the Hollywood gala, was final confirmation that they had made the best possible decision.

Freedom

I deliberately avoid offering too many personal interpretations in this text because I believe that One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a universal story that everyone must filter through their own experiences. When writing the literary original for the film, Kesey certainly had his America and the sense of division that accompanied his intellectual judgment of the situation, as well as the beatnik and hippie ideals of freedom, in mind. On one side, the extremely conservative United States of the McCarthy era, and on the other, the revolution that began in the 1960s, the arrival of a new generation with a completely different definition of freedom. In the 1970s, this debate was still somewhat relevant, though the terminology of the opposing sides had changed. Forman undoubtedly viewed McMurphy’s story through the lens of what was happening in Czechoslovakia. That’s likely why he wanted to turn Oregon State Hospital into an insane asylum, a metaphor typical of his work (The Firemen’s Ball, for example, is a brilliant critique of the system). Jack Nicholson, however, seemed to approach the entire story from the perspective of an individual entangled in life. For him, the system was secondary, and what mattered more was how a person could navigate within it.

In a key scene from Easy Rider, George Hanson (Nicholson) tells Billy (Hopper) that the people watching their motorcycle journey aren’t afraid of them, but of what they represent. Billy, surprised, responds that all people see are two drifters in need of a haircut. Hanson brushes off his joke, explaining that people are scared because the men speeding on motorcycles represent freedom—something they will never experience. This sad and universal truth has always echoed and will continue to echo off the walls of places like Oregon State Hospital.

That’s why, in life, we need people who will lift—or inspire someone else to lift—a sink and smash a hole in a wall that seems insurmountable. It doesn’t matter who they were, what they did, or who they will become. What matters is who they are to us at the moment when their presence is as vital to our lives as air. And when they finally manage to escape toward the mountains, and we gaze out at the world through the shattered wall, we might start laughing like Christopher Lloyd’s character. Because that’s the fate of all madmen.