Myers & Krueger: Iconic Slashers vs. Real-Life Horrors

A devilishly efficient unidentified killer, extraordinarily creative in devising ways to eliminate their victims. They are typically driven by a personal trauma from the past, fueled by a thirst for revenge, elusive, and insatiable.

Blood flows freely, all rules are off the table, and in the end, it’s usually the lone final girl (rarely a final boy) who remains standing, leaving the door wide open for a sequel. The slasher’s victims are young, often attractive, reckless, and immersed in hedonistic pleasures. An unwritten rule dictates that “improper” behavior will be punished. The horror heroine typically avoids such transgressions—she doesn’t binge drink, smoke weed, engage in casual sex, and retains her common sense. In slashers, the complexity of the plot or character development takes a backseat. What matters most is the violence and gore. The more brutal the deaths and the more varied the killer’s arsenal, the better.

This genre of film treads the line between drama and comedy, even veering into grotesque territory, deliberately exaggerated to absurdity, with an unstoppable killing machine at its core. The murderer is indestructible, as strong as an ox, and impervious to blows. They appear almost superhuman, and in some cases, they truly are. Here, brutality and laughter go hand in hand, and slashers are fundamentally meant to entertain and unwind the audience because it’s hard to take them too seriously. Moreover, within the roster of stereotypical characters—the cold mean girl, the weirdo, the stoner-clown, the jock, the promiscuous one, and so on—we can often find parallels to those who annoyed us during high school. Watching their gruesome ends brings a small measure of satisfaction. Admit it—they had it coming!

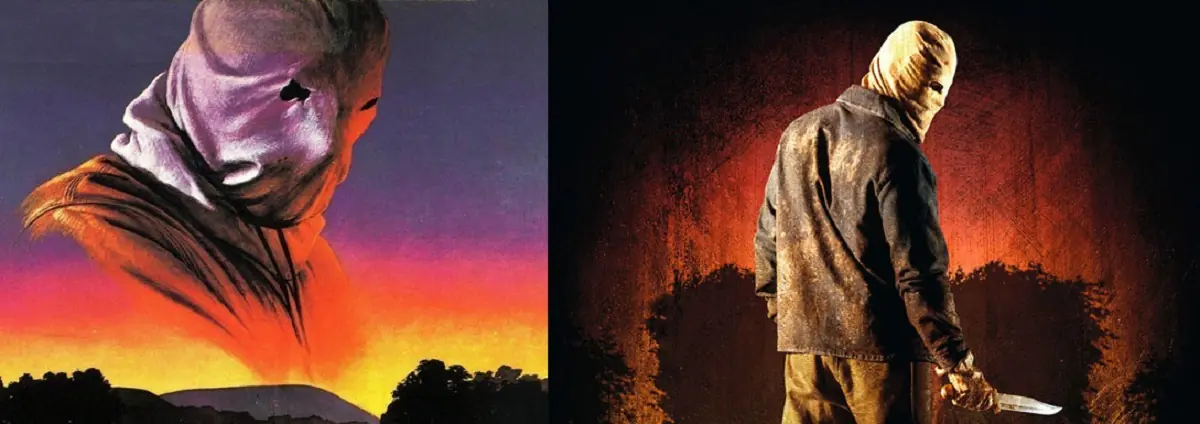

It’s all the more difficult to mentally connect the slasher genre with real life. And yet, many slashers drew inspiration from reality and, in turn, became sources of inspiration themselves. Not all, of course, achieved the scale of The Town That Dreaded Sundown, which has become almost an integral part of Texarkana, Texas’s local history—or at least its folklore.

The killer, known only as the Phantom—he was never caught—attacked eight people between February 22 and May 3, 1946. Over time, even before the film’s release in 1976, and certainly on a larger scale afterward, countless rumors, exaggerations, half-truths, and spine-chilling tales turned the Phantom into an almost mythical figure. Unsurprisingly, this transformation was met with disapproval from the victims’ loved ones, who saw it as a form of glorification. In reality, both the movie and the lore surrounding it functioned more as a coping mechanism for the small community, which feared its peace might someday be shattered again.

Wes Craven’s Scream, written by Kevin Williamson (for the first two films, with Ehren Kruger penning the third), brought a fresh twist to the genre by playing with its conventions and clichés. The first installment premiered in 1996, introducing audiences to Sidney Prescott (played by Neve Campbell), who finds herself hunted by a killer in a grotesque mask—later dubbed Ghostface. Ghostface engages his victims in a sinister game centered around the question, “What’s your favorite scary movie?”

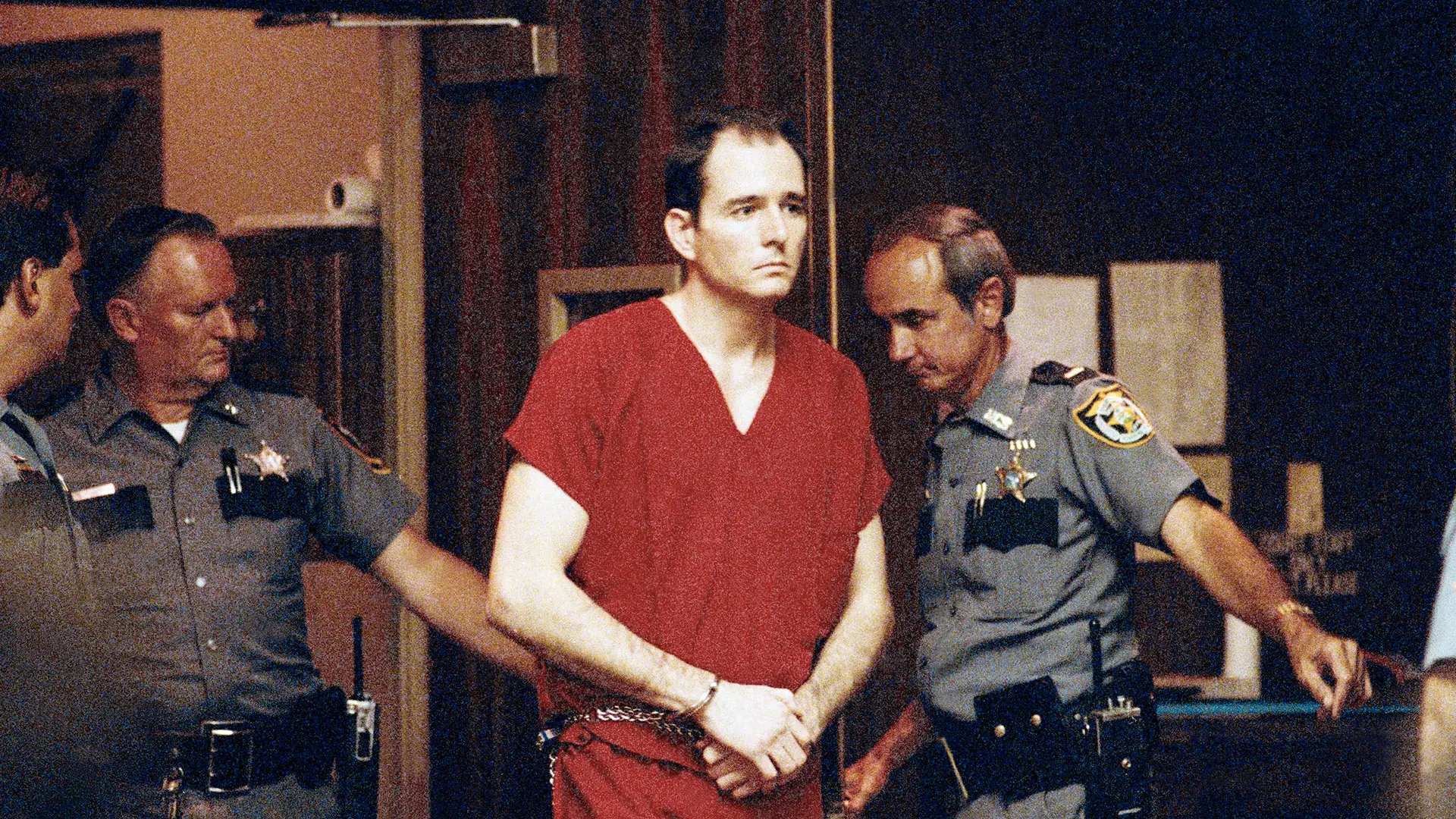

Kevin Williamson’s direct inspiration was the case of Danny Rolling, also known as the Gainesville Ripper, who murdered eight people (including five students) in Florida in 1989 and 1990. Rolling was sentenced to death, and the execution was carried out in 2006. On the surface, the inspiration seems very loose—there was no obsession with movies, let alone horror films, in the case of the Gainesville Ripper. However, Williamson was clearly struck by the overall atmosphere of the events.

For example, Rolling broke into an apartment shared by two female students at night while they were asleep. He entered one of the bedrooms, observed for a moment, but didn’t wake the girl. He wandered through the apartment, checked the second bedroom, overpowered the girl sleeping there, tied her up, gagged her, raped her, and stabbed her to death. Then he returned to the first bedroom to finish what he had started. He posed the victims’ bodies in provocative positions before leaving. Rolling repeated this pattern in every break-in, sometimes using mirrors to enhance the macabre effect.

Worse still, when news of a killer on the loose spread, the campus implemented maximum security measures, yet they proved insufficient. To make matters worse, the police’s attention focused solely on a scapegoat: Edward Humphrey, a student who fit the media’s image of a suspect due to his scarred face and long history of psychiatric treatment. Although his name was officially cleared later, the trauma he endured was immense. The chaos on campus, blind accusations, growing panic, and, above all, the killer slipping through the cracks anonymously like a shadow—these elements of the case formed the foundation of Williamson’s initial screenplay draft, which eventually developed into Scream.

The Scream trilogy also sparked its own share of controversy due to events it directly inspired. The most infamous of these was the death of Gina Castillo in 1998. The case was quickly dubbed “The Scream Murder” by newspapers. Gina’s son, 17-year-old Mario Padilla, and his cousin, 16-year-old Samuel Ramirez, brutally murdered her (45 stab wounds) to steal her savings. The money was intended to buy Ghostface costumes, masks, and a voice changer. Fortunately, the young killers were caught before they could embark on their planned killing spree. Their first target was intended to be one of Padilla’s schoolmates, who bore a striking resemblance to Drew Barrymore. When asked about their motives, the boys unanimously stated that they were inspired by watching Scream and Scream 2.

In 1999, Belgian truck driver Thierry Jaradin murdered teenage Alisson Cambier after she rejected his advances. Before committing the crime, he donned a Ghostface mask and cloak and armed himself with two large kitchen knives. During his interrogation, he confessed that it was a premeditated murder and admitted that the idea first came to him after watching Wes Craven’s films. There is also the case of 13-year-old Ashley Murray, who fortunately survived despite his closest friends, Daniel Gill and Robert Fuller, attempting to bring the plot of Scream to life. Among their belongings, numerous sketches of the Ghostface mask were found.

Craven’s trilogy was also cited in debates about the influence of media, films, and video game violence on youth, particularly following the Columbine massacre. An anonymous American judge, referring to the Gina Castillo case, remarked that ironically, the deconstruction of the horror genre presented in Scream, despite its satirical intent, turned out to be an excellent “how-to guide for creating an effective killer.”

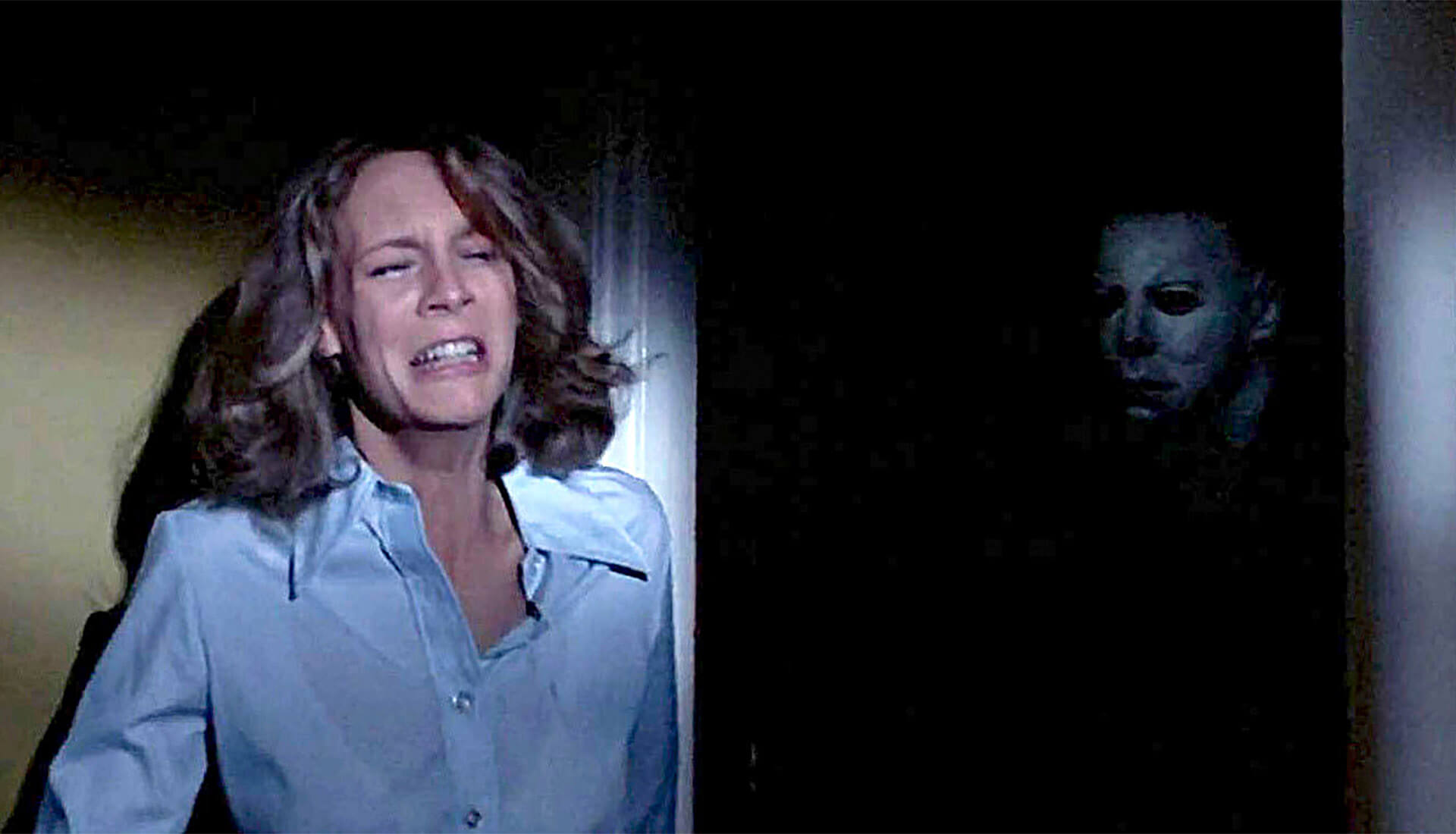

In early 1978, Irwin Yablans, who would become the executive producer of Halloween, approached John Carpenter with a proposal for a horror film featuring two key elements: a babysitter and a single-night setting. Yablans even wanted to call it The Babysitter Murders, as nearly every American had grown up with a babysitter, a figure often associated with “the innocence of youth.” However, Carpenter came up with a better idea: one night, but make it Halloween.

Carpenter had a very specific vision for the killer: the embodiment of absolute evil, a primal, unstoppable, almost supernatural force destroying everything in its path. But where did the idea for Michael Myers come from? Unlike some of his peers (such as Wes Craven), Carpenter never liked delving too deeply into the details of his inspirations. He did admit, however, that during his college years, he participated in a trip to a mental institution in Kentucky, where he wanted to meet the most seriously ill patients. He vividly remembered a boy suffering from schizophrenia, whose eyes he described as showing “pure evil.” This encounter was echoed in the words of Dr. Loomis (Donald Pleasance) in the film when he describes Michael:

I met this six-year-old child with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and the blackest eyes… the devil’s eyes. I realized what was behind those eyes was purely and simply… evil.

One of Carpenter’s most intense experiences as a viewer had been watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in the 1970s, which inspired him to create a killer as distinctive and iconic as Leatherface. He also wanted to set the story in a town so anonymous and ordinary that it would feel familiar to almost everyone. In the original script, Michael Myers was referred to only as The Shape. His motivations and backstory, while partially revealed, are largely irrelevant, as it was the randomness of the killer’s actions that Carpenter believed would evoke the most fear. He could do anything. He could be anywhere. He was capable of anything.

The first Halloween not only launched a franchise but also established a cult following, primarily centered around Michael Myers as the embodiment of evil. The second installment, released in 1981, had an unfortunate influence on a man named Richard Delmer Boyer. Boyer, a drug addict and alcoholic, visited an elderly couple he knew, intending to borrow money. However, as his defense later argued in court, he experienced a drug-induced psychotic flashback to a scene in Halloween II where a similar elderly couple is murdered. He reenacted the scene in real life. Boyer later claimed to remember nothing of the event. During his trial, Halloween II was screened for the jury as evidence, marking the first instance of such a practice in American legal history.

In 2007, Rob Zombie directed a remake—or rather, a reinterpretation—of the original Halloween. The film was largely met with negative reviews, partly because Zombie stripped the story of its greatest asset: the ominous anonymity and symbolic nature of Michael Myers. Nevertheless, one particular scene, where Myers murders his stepfather, sister, and her boyfriend, deeply resonated with 17-year-old Jake Evans. He was fascinated by the killer’s complete lack of empathy, feeling he could relate. In his four-page confession, Evans wrote:

I was impressed by how relaxed he was (…) and how little remorse he felt about it. I thought if I were in his place, I’d feel the same way.

And he did. After shooting his mother and sister, his main thought was that it was now time to move on to other family members. Fortunately, this didn’t happen. In concluding his confession, Evans wrote:

I know I’m done with killing (…) The memory of last night will haunt me forever.

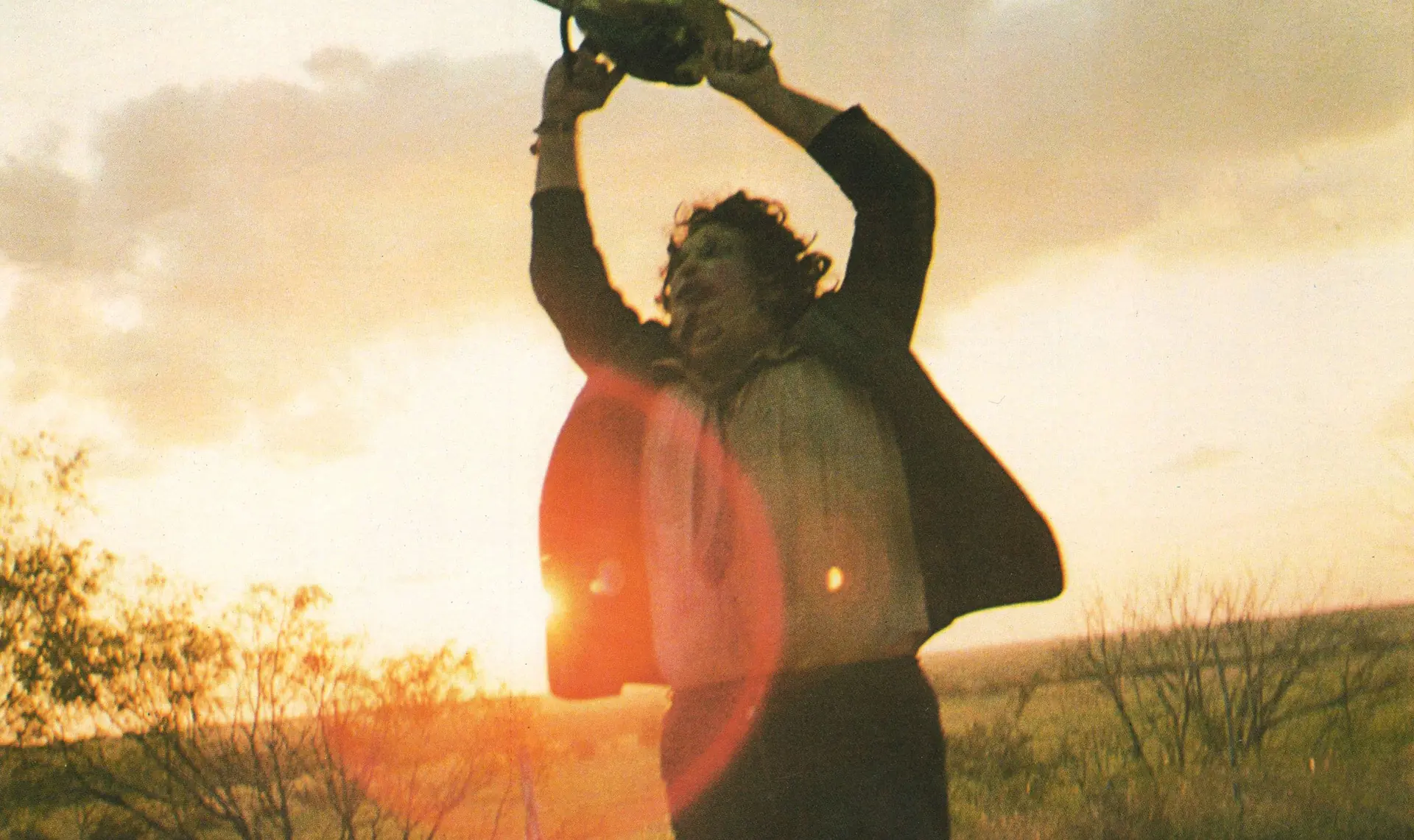

The Real-Life Inspiration Behind Leatherface

The origins of Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre are widely known—he was inspired by the infamous Ed Gein. Gein’s macabre actions also influenced the characters Norman Bates from Psycho and Buffalo Bill from The Silence of the Lambs. Gein, obsessed with creating a “woman suit” from human skin, was a grave robber and the murderer of at least two women. However, in a 2004 interview, Tobe Hooper revealed that Gein wasn’t his sole inspiration. He also cited Elmer Wayne Henley.

Born in 1956, Henley became an accomplice to serial killer Dean Corll, infamously known as the “Candy Man.” Between 1970 and 1973, Corll abducted, tortured, raped, and murdered at least 28 boys. Henley, along with another accomplice, David Brooks, was tasked with luring unsuspecting victims. They were paid $200 for each boy they brought to Corll. The killings continued until Henley brought a 15-year-old girl, Rhonda Williams, alongside a targeted boy. This disrupted Corll’s fantasy. Enraged, Corll nearly shot Henley, who begged for his life, promising to assist in torturing the two captives. While Corll focused on the boy, Henley turned his attention to Rhonda. In an almost surreal moment, Rhonda looked up and asked, “Is this really happening?” Henley confirmed. “And you’re not going to do anything about it?” she pressed. Astonishingly, her words spurred Henley to act. He grabbed a gun and shot Corll. Henley then freed the captives and called the police.

In the aforementioned interview, Hooper stated that he was intrigued by something in Henley, which he referred to as “moral schizophrenia.” On one hand, this skinny, unassuming 17-year-old was a ruthless murderer—he had killed at least six people in total. On the other hand, when leading police to the burial sites of the murdered boys, he said with dignity:

I killed these people. It’s only right that I face the consequences like a man.

As for events that could successfully inspire the plot of Friday the 13th, one does not need to look to the United States but rather to Finland. In 1960, four teenagers went camping near the picturesque Lake Bodom, much like their cinematic counterparts would do years later at Crystal Lake. Between 4:00 and 6:00 in the morning, three of them were murdered, while the fourth, seriously injured, barely survived. To this day, it remains unknown who attacked the teenagers and why, although there were several suspects, including the sole survivor, Nils Gustafsson. Unsurprisingly, over the years, numerous rumors and conspiracy theories have emerged. Shocked and wounded, Nils incoherently mentioned “black and red burning eyes” that “emerged from the darkness,” further fueling the sensationalism of the event. Another chilling detail was that the murderer attacked the teenagers through the tent wall rather than directly confronting them.

Based on these events, the Finnish horror film Bodom was made in 2016. However, decades earlier, in 1980, Finland’s “cursed lake” transformed into Crystal Lake in Friday the 13th. The No-Be-Bo-Sco Camp in New Jersey, which served as the iconic Crystal Lake Camp in the first film, takes immense pride in its cinematic legacy. On the camp’s website, fans can even purchase fragments of the dock featured in Friday the 13th or dice carved from wooden pieces of the wall of one of the cabins.

I delved deeper into the connections, both close and distant, between the Saw series and reality in a previous piece about Jigsaw. Here, it’s worth mentioning two events inspired by the franchise.

The first is the case of Beverly Dickson. Two teenage girls decided to play a prank on her by recording a message that began with the infamous line, “I want to play a game…” The message informed Beverly that one of her friends was trapped somewhere in her house, which would fill with toxic gas within ten minutes. “You must decide whether you want to live or die,” the voice continued. Beverly was so terrified that she suffered a massive stroke. To this day, she struggles with sleep issues due to what the pair of 13-year-olds thought was an “innocent” joke.

An even worse scenario nearly unfolded in Salt Lake City, where a mother was horrified to overhear her 14-year-old son and his 15-year-old friend planning how to kidnap, torture, and murder people. The teenage pair had already meticulously designed the details of their “games” and drafted a list of potential victims, which included a police officer and two schoolmates. Fortunately, rather than dismiss their conversations as baseless fantasies, the mother reported the matter to the police. The boys later admitted they had even purchased cameras and recording equipment, intending to document their crimes “just like Jigsaw.”

One of the more shocking, though not entirely confirmed, slasher-inspired crimes is the 1993 murder of two-year-old James Bulger, who was abducted and tortured to death by two ten-year-olds, Robert Thompson and Jon Venables, in Liverpool. Some British tabloids immediately picked up on the information that one of the films rented by Venables’ father in the month leading up to James’ murder was Child’s Play 3. In the film, the evil doll, Chucky, is inhabited by the vengeful spirit of the serial killer Charles Lee Ray (a combination of Charles Manson, Lee Harvey Oswald, and James Earl Ray), which is possibly one of the most ridiculous ideas in horror history. It was never definitively confirmed whether Jon Venables had seen the film, but there is a notable coincidence: in one scene, Chucky is splashed with blue paint. During the torture of James Bulger, one of the boys poured blue paint into the child’s eye. In total, the pathologist counted 42 injuries on the boy’s body, and it was impossible to determine which one was fatal. The Child’s Play connection sparked a heated media debate about restricting access to certain video categories for underage customers in video rental stores.

When Hellraiser hit theaters in 1987, audiences were already somewhat fatigued with the formula of classic slashers following the initial excitement sparked by Halloween, Friday the 13th, and A Nightmare on Elm Street. They were seeking something fresh, and undoubtedly, Hellraiser delivered that. The first outline of the Pinhead character appeared in a 1973 short story by Doug Bradley titled Hunters in the Snow, but Clive Barker transformed and expanded this idea in his 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart, which ultimately served as the basis for the film adaptation. Barker was fascinated by the concept of the line between extreme suffering and extreme pleasure, as well as the growing desensitization to everything—where even a major shock fails to disrupt one’s numbness for long.

To create the character of Pinhead (who, by the way, Barker despised that name and referred to the character more as the “lead cenobite” or “priest”), Clive Barker visited BDSM clubs in New York and Amsterdam, delved into Catholic ideas of purgatory, and explored the intricacies of the punk subculture. The exact design of Pinhead’s skull came from a book on African fetishes, where Barker read about skulls carved from wood and studded with hundreds of nails. The style created for Hellraiser was incredibly artistically inspiring and its spiritual heirs can be seen in films like Dark City, Cube, The Cell, and Event Horizon. Unfortunately, the influence of Hellraiser extended beyond filmic experimentation.

Edward Bagley from Missouri ran a BDSM-themed website for several years, featuring extreme content. The main character was, as he claimed, his partner with whom he explored absolute obedience, submission, trust, and the extension of the boundaries of pain, humiliation, dominance, and pleasure, with mutual consent. In reality, in 2002, along with his wife, he imprisoned a sixteen-year-old runaway, whom they kept as a slave to their brutal sexual fantasies for six years. He beat, humiliated, drugged, tortured, and shared her with anyone who paid for the pleasure of tormenting the woman. She was whipped, kept in a cage, electrocuted, tied up, and starved. In one post on his now-defunct website, Bagley confessed that after watching Hellraiser, he developed a desire to become a “master of pain” himself. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison, though he attempted to argue that the girl “enthusiastically consented” to all the sadomasochistic practices to which she was subjected.

And finally, perhaps the most intriguing story of all: the origin of the unforgettable character from A Nightmare on Elm Street, Freddy Krueger.

The story that Krueger was named after a boy who tormented Craven during his childhood has never been officially confirmed. However, the director did admit that the appearance of the horror icon was based on a homeless man he encountered as an eleven-year-old. The idea for the glove with blades came from a particular habit that Craven’s cat had of scratching furniture. But where did the actual story come from?

The inspiration for the story came from an article about a Cambodian refugee family. One of the sons could not shake off his trauma and began suffering from recurring nightmares. He confided in his parents that he was constantly being chased in his dreams, that someone was trying to catch him. Much like the characters from A Nightmare on Elm Street, he tried to avoid sleep, drinking vast amounts of coffee, but the need for sleep proved stronger. One night, the boy’s parents were awakened by a terrifying scream, and when they rushed to his bedroom, he was already dead. He died during a nightmarish dream.

This detailed story was recounted by Wes Craven during an interview in 2008, where he added that the article was published in the Los Angeles Times. However, an interesting fact is that Adam Bulger, a journalist for the website vanwinkles.com, attempted to find the original source of this story but could not find any article of that nature in the newspaper’s archives. Instead, he came across an intriguing medical phenomenon commonly referred to as “Asian death syndrome.” The first case was recorded in 1977, and by the mid-1980s, 110 men had died in their sleep. All were young, seemingly healthy, and of Asian descent. Among them were many refugees, including from Vietnam. The cause of this sudden epidemic of deaths, which peaked in 1981 and then gradually subsided, was never explained.

In 2011, Shelley Adler published a book Sleep Paralysis, in which she suggested that the cause might be a mythical beast from Asian folklore called Dab Tsog, which preys on its victims in their sleep. Adler wrote that belief in the creature was so strong that people literally died from fear. In other words, if you believe Freddy is after you, he might just be after you.

That said, Craven’s sensational story seems to be a fantasy built from several different pieces of various stories that just sounds good. Bulger began his investigation before Craven’s death, but unfortunately, the director declined to give an interview during which the journalist had hoped to ask him for the historical, yellowed clipping from the Los Angeles Times—if, of course, the article was authentic and if Craven had kept it.

Without a doubt, Daniel Gonzalez was a real-life case where ambition mirrored that of Freddy Krueger. In 2004, over the span of two days, he attacked passersby, primarily the elderly and infirm, on the streets of London. He killed four people and seriously injured two others. Each murder was described in letters he wrote to himself, where he marveled at how much he resembled Krueger and how “orgasmic” his experiences were during the killings. It seemed he didn’t just identify with Freddy, but also with Jason, as during some of his attacks, he wore a hockey mask.

After his arrest, Gonzalez attempted suicide by biting through an artery. He was saved, but his next attempt was successful: this time, he used the edge of a broken CD case. One could say that in his own twisted way, he achieved the success he sought, as the newspapers affectionately dubbed him the “Freddy Krueger Killer.”