10 Forgotten Samurai Movies. The Fading Gleam Of The Sword

Hana wa sakuragi, hito wa bushi

Among flowers, the cherry blossom; among men, the warrior

(a Japanese proverb about samurais)

Eleven Samurai / Jûichinin no samurai, dir. Eiichi Kudô

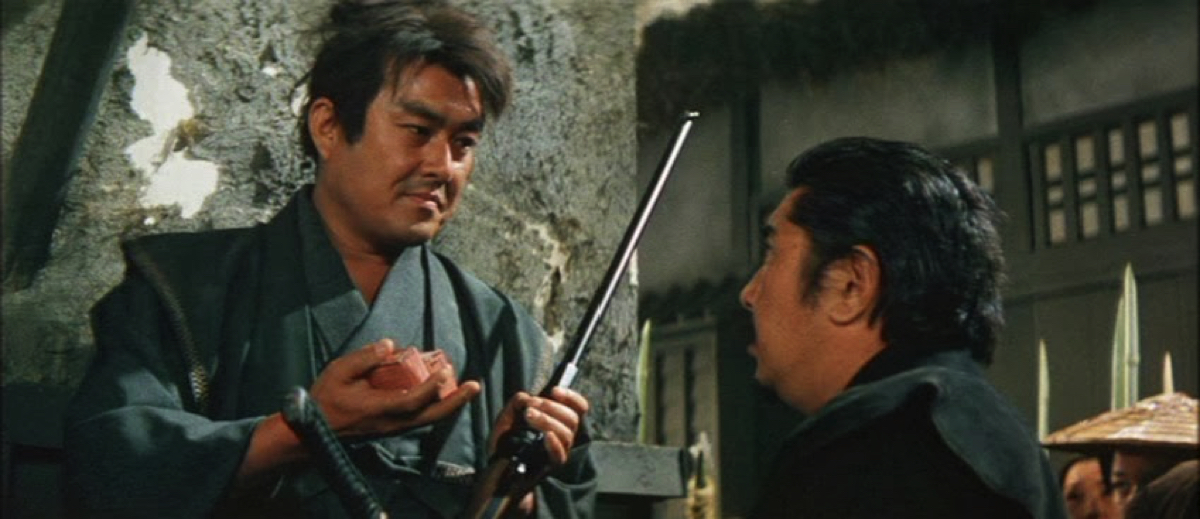

Between 1963 and 1967, Eiichi Kudô directed three films that were titled The Thirteen Assassins (1963), The Great Killing (1964), and Eleven Samurai (1967) in the West. The plots of these films are similar, each featuring a group of samurai rebelling against the nobility to defend samurai traditions. Therefore, the films have been grouped under the label Samurai Revolution Trilogy. The title that initiated this series is quite well known, as Takashi Miike remade it successfully in 2010 as 13 Assassins. The last part of the trilogy, sponsored by the number 11, although seemingly conventional, turns out to be a well-crafted work, full of surprising twists and delivering the kind of experience expected from a samurai drama.

The rule of the twelfth shogun of the Tokugawa clan did not yet herald the final end of the samurai era. However, corrupt and arrogant officials were a thorn in the side for those who lived by specific rules, enjoying stability and peace. When the shogun’s brother, an impulsive and uncouth man, commits a senseless crime, the nobles— to protect their position and the authority of the supreme commander—assign him protection instead of punishing him. This incident leads to the formation of a group of eleven rebels aiming to bring justice to the unpunished heir. Among the protagonists, there are no charismatic figures like Toshirô Mifune, Tatsuya Nakadai, or Tetsurô Tanba, but this (paradoxically) makes the story seem closer to reality and unpredictable. Behind the camera, there isn’t an outstanding individual, but the director cannot be accused of incompetence, as he has crafted several excellent scenes (an intriguing prologue, an ambush in the forest, a fight in the rain, etc.) and guided the actors in a way that maintains the story’s appeal and keeps the audience interested.

The noble person is distinguished by dignity, not pride. The common person may be proud, yet lacks dignity. (Confucius)

Steel Edge of Revenge / Goyôkin, dir. Hideo Gosha

Hideo Gosha, who had already impressed with his debut film Three Outlaw Samurai (1964), created a work at the end of the decade that is hard to overlook. Steel Edge of Revenge can be seen today as the beginning of the end of the genre, much like Sam Peckinpah‘s The Wild Bunch (1969) heralded the end of the western. And similar to Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961), it received a western remake titled The Master Gunfighter (1975) directed by Tom Laughlin. But most importantly, this film has not aged a bit and still makes a colossal impression. The enigmatic prologue floods the screen with unease, but the true visual masterpiece is the climactic scene. The recipe for such a spectacle is simple – plenty of snow, turbulent sea waves, the darkness of night, and raging fire. The soundtrack also greatly helps; in Masaru Satô’s music, there is nostalgia, drama, and horror, which, combined with the sound of crows, creates an eerie atmosphere.

The film, however, offers much more than just visual and auditory appeal. We have two protagonists who understand the concept of honor differently. Magobei Wakizaka believes that samurai honor involves rejecting selfishness and defending the weak, but Chamberlain Rokugo Tatewaki holds a different view – loyalty to one’s clan is fundamental, and if something threatens it, it must be eliminated by any means. This leads to the massacre of a fishing village – the target is a ship loaded with gold. To seize the precious cargo, representatives of the Sabai clan kill the witnesses, the defenseless fishermen, and take the loot. Magobei becomes an unwitting accomplice to the crime. Tormented by guilt, he leaves his family (the wicked chamberlain is his brother-in-law), but after three years, the past returns. Tatewaki plans to seize another gold shipment at the expense of the villagers – this time, however, Magobei does not intend to stand idly by. He tries to wash the blood off his hands by preventing another crime.

In the 1960s, Hideo Gosha maintained a consistently high standard, but Steel Edge of Revenge is, for me, an extraordinary work. The plot, the central theme, the atmosphere, the acting – all these elements create a unique depiction of a bygone era. At the forefront is Tatsuya Nakadai, a significant figure in the genre. He played memorable roles in Harakiri (1962) and The Sword of Doom (1966). He also appeared in Hideo Gosha’s Hitokiri (1969), but Steel Edge of Revenge stands out with four excellent performances. Thanks to actors like Tatsuya Nakadai and Tetsurô Tanba, the duel between the characters is intriguing. Both can act restrainedly but in a way that reveals the deep-seated suffering of their characters. If one of these protagonists had been played by Toshirô Mifune, he would undoubtedly have dominated the film, but here we have two equally significant figures. The female role is also very good – Ruriko Asaoka as the chosen one of the gods, a woman cruelly tested by fate, unable to keep her emotions in check. A few scenes were stolen by Kinnosuke Nakamura, who played a mysterious ronin whose motives are not entirely clear, i.e., it is uncertain whether the scent of gold or justice attracts him more. Abroad, this actor is known as the driving force behind the aforementioned Bushido: The Cruel Code of the Samurai. In Japan, he is known for his role as Musashi Miyamoto in six films by Tomu Uchida (an old hand in the industry since the 1920s).

The content of Steel Edge of Revenge (as the film is titled in the USA) is Confucian in spirit. Confucius taught that it is cowardly to know what is right and not do it, and the gravest error is to commit a mistake and not correct it. These words fit the stance of the character played by Tatsuya Nakadai. He realizes he did wrong, but fate gives him a chance to redeem himself – to regain his honor and become a person deserving of the title of samurai. With his film, Hideo Gosha tried to answer the question of why the samurai is a species doomed to extinction. When loyalty and honor, the two most important values, cause division instead of unity, the end is near. Because these attributes should be inseparable, like a splendid sword forged in the Echizen province. If the sword breaks, the samurai dies; if the code of honor loses its significance, everything ends – cherry blossoms wither, and the sun sets over the country. The final “dance of demons” is a symbolic funeral of the samurai caste. Although the film has the character of an impressive adventure spectacle, it also contains many interesting observations and reflections. For me, it is number one in this ranking.

Killer’s Mission / Shokin kasegi, dir. Shigehiro Ozawa

Like most samurai films, the script for this piece is based on historical sources, but in this case, that doesn’t matter much. There’s no point in questioning how much of the story is true, as it quickly becomes clear that we are dealing with a purely entertaining production. The film can be seen as Japan’s response to Bond, specifically You Only Live Twice (1967). Shikoro Ichibei is a powerful and clumsy man who doesn’t look like either a spy or a master swordsman. But James Bond could learn a lot from him, not only in the art of combat but also in dealing with women (he can be rough, but sometimes his tough guy mask drops). Like his Western rival, Ichibei is equipped with ingenious gadgets (for example, his cane is not only a sword sheath but also a telescope). He is not the only spy in this film – he teams up with a woman who uses a deadly comb filled with viper venom.

In 1974 director Shigehiro Ozawa made his crowning achievement – the karate film The Street Fighter starring Sonny Chiba. Killer’s Mission also possesses cult film characteristics. It is inventive and charmingly kitschy, with action as fast-paced and improbable as Bond films, and the main character stands out from the rest. A few words about the plot: in the Hōreki era (mid-eighteenth century), a Dutch ship arrives at the shores of Japan; when the European ambassador fails to reach an agreement with the shogun, he forms an alliance with the Satsuma clan, which aims to overthrow the Tokugawa family’s rule…

Actor Tomisaburô Wakayama (known for the Lone Wolf and Cub series) excelled in the role of the super-agent and humorously parodied his brother Shintarô Katsu (from the Zatôichi series) in a scene where he pretended to be a blind masseur. However, Wakayama is not a lone wolf here, as Yumiko Nogawa (agent Kagero) and Chiezo Kataoka (Satsuma clan ambassador) also create very interesting performances, only surpassed by the protagonist in combat skills. At that time, Kataoka was a veteran of Japanese cinema, increasingly falling into a routine. He became an icon of samurai dramas back in the 1920s and ended his career with over three hundred roles (IMDb lists only half of his achievements). Composer Yagi Masao did a good job on Killer’s Mission, creating music in a European style, which made the film resemble a Euro-western. The discussed film is also known (in the DVD market) as Bounty Hunter 1: Killer’s Mission and is the beginning of a series that includes films: Fort of Death (1969, dir. Eiichi Kudô) and Eight Men to Kill (1972, dir. Shigehiro Ozawa), as well as a twelve-episode TV series Bounty Hunter (1975), where the similarities to spaghetti westerns become even more apparent.

When fighting with an opponent, you are not fighting with a person,

but with the evil that he embodies through his actions

(Munenori Yagyu – The Art of War of the Yagyu Family)

Shura / Demons, dir. Toshio Matsumoto

Of all the films presented here, this one surprised me the most. First: I didn’t expect a black-and-white film from the seventies. Second: the title suggested that supernatural phenomena would appear. Third: despite the absence of supernatural phenomena, the film has a lot of horror elements. Fourth: the lead actor Katsuo Nakamura turned out to be the younger brother of Kinnosuke Nakamura, whose name appears most frequently in this compilation. Fifth: the creators managed to achieve an extraordinary, very stifling and claustrophobic atmosphere, as the cinematographer did not shoot spectacular outdoor scenes but theatrically darkened sets. However, despite the theatricality, so much happens here that it’s impossible to look away from the screen.

After the era of widescreen and colorful blockbusters, a film directed by Toshio Matsumoto might seem like a step backwards, but that’s a misleading impression. The typical use of lighting in early cinema introduces a suitable dose of horror and tension, but the most significant aspect is not the form but the content of the message. The message is that emotions and feelings destroy people, turning them into demons. If we didn’t have emotions, we wouldn’t have a propensity for violence either. It all begins with a romance between a ronin and a geisha (very successful roles by Katsuo Nakamura and Yasuko Sanjo), which transforms into a tale of bloody revenge presented in a non-standard form. The intrigue unfolds in a setting darker than night (splendid sequences where lit lanterns are carried by unseen figures), evoking a dream-like vision. The dreaminess is reinforced through repetitions that create an impression that truth merges with illusion. This is what hell looks like, says the director – when people have something on their conscience, they live in fear. The main sin is emotions, but the strongest are those towards monetary means (a hundred ryo is the most important, says one of the characters).

Yagyu Clan Conspiracy / Yagyû ichizoku no inbô, dir. Kinji Fukasaku

Countless films have been made about the famous swordsman Musashi Miyamoto, played by the most outstanding Japanese actors. Much less frequently portrayed on screen are the representatives of the Yagyū family, owners of one of the oldest fencing schools, Yagyū Shinkage-ryū. This illustrious clan, significant to the martial arts, became the subject of a film directed by Kinji Fukasaku, known for war epic Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) and the brutal dystopia Battle Royale (2000). However, this director is primarily known for gangster dramas (his films under the label Battles Without Honor and Humanity were particularly popular). In 1978, he completed two historical dramas. One was The Fall of Ako Castle, another successful interpretation of the story of the 47 rōnin, but more intriguing due to its less clichéd historical aspect was Yagyu Clan Conspiracy. The film was made with proper scope, at times unpredictable, and brilliantly cast. Leading the ensemble, as mentioned several times before, is Kinnosuke Nakamura, from the renowned acting family and descendant of kabuki theater stars. His son, named Jūbei, was played by Sonny Chiba, with supporting roles filled by Isuzu Yamada, memorable as Lady Macbeth in Throne of Blood (1957), Tetsurō Tanba as a mysterious swordsman (a disappointing performance), and Toshiro Mifune as a dignified daimyō.

The film is set during a fratricidal struggle for power following the death of the second Tokugawa shogun. A group of thieves breaks into a tomb and steals… the stomach of the deceased leader. This act is meant to serve as evidence that the shogun was poisoned. These suspicions quickly prove true. The plot was devised in response to the shogun’s opposition to the succession of his eldest son, who was unsuitable due to his ugliness and stuttering. Leading the conspiracy was Yagyū Munenori. His enemies were supporters of his younger (and more handsome) brother.

Two excellent actors, Kinnosuke Nakamura and Sonny Chiba, played father and son, but they had only a few scenes together, the best being the last. It vividly indicates that the conflict is about more than fratricidal strife. This scene highlights the clash of two attitudes, two worlds. In the first, more sterile world, there is a political struggle for power, deceitful and dishonorable. Also prevalent here is a difficult-to-understand servitude, adhering to a specific hierarchy and decisions that dictate the fate of subjects. In the second world, we observe life on the edge, a playground for warriors. In this theoretically inferior environment, there is equality and loyalty, alongside the conviction that every life is precious.

Yagyu Clan Conspiracy is a magnificent cinematic feast. The director’s masterful hand is evident at every turn, and the actors also maintain a high standard, elevating the production to another level. Discussing this film, one must note that the creators departed significantly from historical sources. They convincingly explained deviations by noting that chronicles often erased sensitive issues, such as subjects’ betrayal of feudal lords. History written in books abounds in distortions and hypotheses. Reality is more complex, and what truly matters are not dates or events but people, who shape history. Their diverse characters stand out from the crowd—it is not armies that wage war, but individual units with varying temperaments. This multitude of characters symbolizes this, although some characters, of course, could not be fully developed. 130 minutes proved insufficient for the film to be complete and not superficial. The action unfolds swiftly, without any drag, with a large dose of emotion and surprising plot twists. Despite the crisis in Japanese cinema at the time, a sensational historical epic emerged that rivals the greatest achievements in the genre’s history.