The Myth of the Samurai and Its Deconstruction in Japanese Cinema

Who was “the last samurai”?

Slowly, one by one, he unbuttoned the flat brass buttons. A tanned chest emerged, followed by his abdomen. He unbuckled his belt and unbuttoned his pants. A snow-white loincloth peeked out, and the lieutenant slid it down, revealing more of his stomach, then took the blade wrapped in white cloth in his right hand… The lieutenant pushed the sword forward, lifted his hips slightly so that the upper half of his body hung over the end of the sword. His arms, tensely strained under the uniform, indicated that he was gathering all his strength. He decided to thrust deeply and decisively into the left side of his abdomen. A sharp cry pierced the silence of the room. Samurai

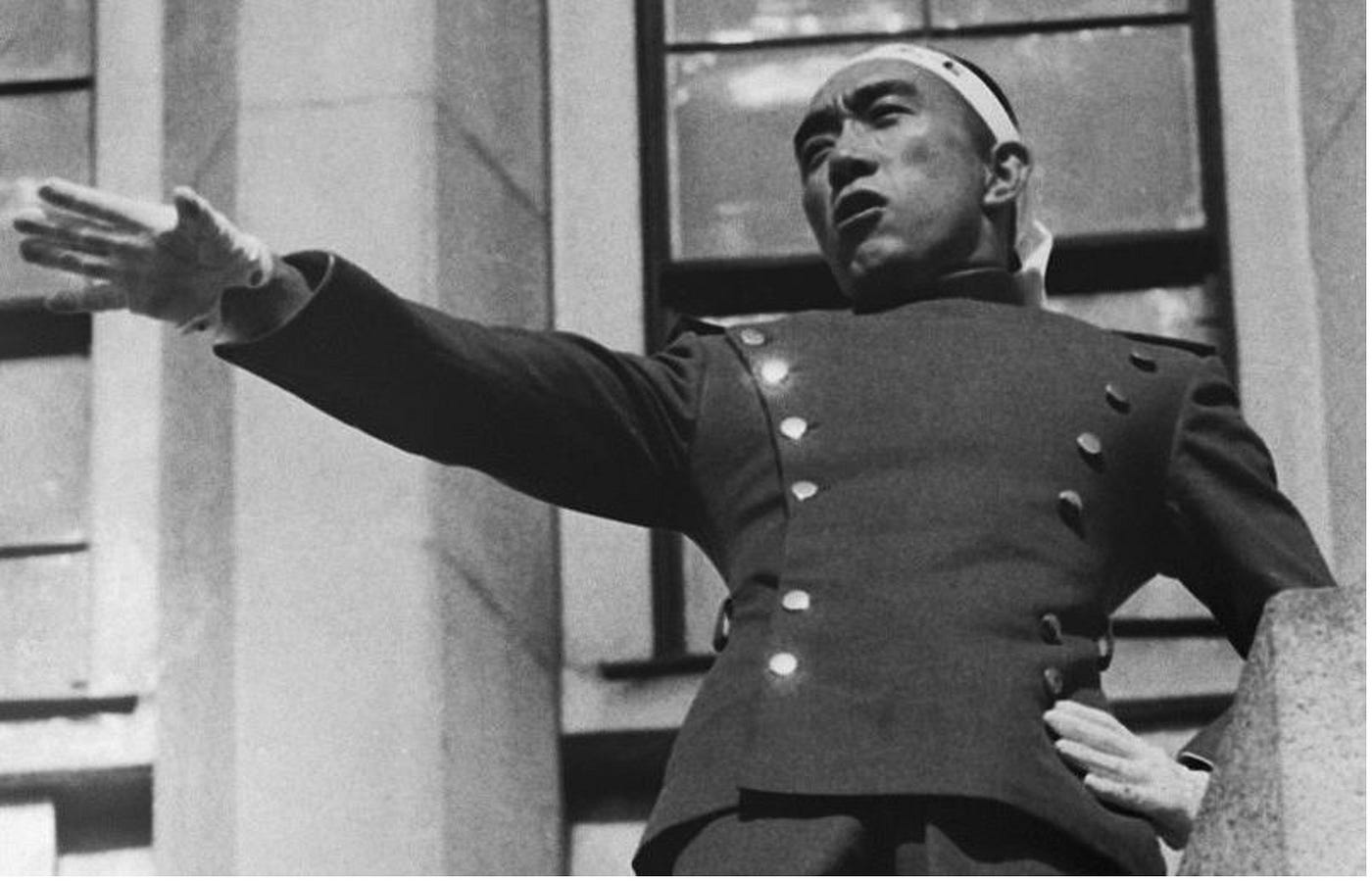

Mishima Yukio, a prominent Japanese writer and playwright, enacted his own words on November 25, 1970, by committing ritual suicide, known as seppuku, after a failed coup attempt.

For most, he was merely a troublemaker and a fool, for a few – the last bastion of traditional samurai ideals in twentieth-century Japan. His act, which would have likely met with widespread approval just a few decades earlier, made him a cheap scandalist in the latter half of the 20th century. Has Japan changed so much to forget its heritage? Or perhaps the samurai ideals and a specific understanding of honor no longer have a place in the modern world?

It is impossible to answer these questions unequivocally. Especially since the figure of Saigo Takamori, “the rebel held up as a model in Japanese textbooks” (as called by historian Mark Ravina in his book The Last Samurai), is still revered with incredible fervor by the Japanese community. Regardless of the answer, the samurai in the twentieth century became not only a part of Japanese culture but almost a global property, as evidenced by Edward Zwick’s 2004 film

The Last Samurai, loosely based on Takamori’s life. However, is the portrayal of Japanese culture by the American film industry a true reflection of samurai? Can a film accurately depict the realities of a samurai’s life?

Ronin – the Japanese cowboy?

In the collective human consciousness, the samurai is a solitary figure, silhouetted against the setting sun, walking towards further adventures. This image of the samurai-cowboy has been reinforced over the years by various films, comics, and other mass culture products, placing the samurai’s history on par with the adventures of lone gunmen from the Wild West and attracting adventure enthusiasts worldwide.

However, as with the myth of the cowboy crafted by Hollywood and its accompanying attributes, the myth of the ronin, a samurai without a master, has also been debunked by historical records. The ronin, a wanderer and romantic, often a “sword artist,” following a path of honor and prudence, seeking inner harmony, bringing liberation, and helping all innocent people encountered, often conflicts with the image painted by history.

In the dark era of the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868), the status of a ronin often equated to a death sentence. The ruling shoguns, particularly in the early years of their hegemony, were paranoid about losing power to rival houses and felt threatened by the growing feudal lords known as daimyo. As a preventive measure, the shogunate created a long list of prohibitions and orders, serving as a pretext to eliminate rivals, often imagined. Through dishonest means, the Tokugawas managed to force feudal lords to commit seppuku, resulting in many samurai becoming unemployed. The Tokugawa code also prohibited samurai from taking up paid work, and since the country was not at war due to the constant drive for centralization, ronins were often doomed to starvation, crime, or seppuku.

The last solution is vividly illustrated by Masaki Kobayashi in his masterpiece Harakiri (originally Seppuku) from 1963. This film is set in the Tokugawa era, dating to 1630. At that time, ronins seeking employment resorted to various tricks to secure means of living, unable to prove their worth in battle. Some of them, to preserve their honor, asked for permission to commit ritual suicide at the residence of a nearby daimyo. Their readiness to die impressed the feudal lords, which often resulted in employment offers. However, soon these actions were corrupted by samurai seeking to extort money from the daimyo, as a samurai corpse lying in a pool of blood on the palace steps was dishonorable. Fearing such a vision, daimyo often offered financial aid to ronins to keep the specter of death away from their home. In Harakiri, we learn the story of Motome Chijiwa, a young samurai; his clan was disbanded by the shogunate, and without means to treat his child, he resorts to the previously mentioned dishonorable act. Hoping to be accepted among the daimyo’s soldiers, he is met with disappointment. Humiliated and mocked by other samurai, he is forced to commit seppuku with a bamboo sword, as it turns out he sold the real, steel one to pay for his child’s treatment. This part of Kobayashi’s multi-layered work illustrates the cruelty hidden under the guise of the bushido code. The principles themselves were not inherently bad, but their enforcement, after being adapted for private needs, was likely not an isolated occurrence. Hiding behind the code, denying Motome a bit of compassion and common human mercy, the samurai of the aristocratic lineage condemn him to a cruel death – all in the name of law.

The character narrating the above events to the audience is the father-in-law of the young samurai, Hanshiro Tsugumo. The old warrior comes seeking revenge at the same residence where his son-in-law died. Prior to this, he finds and duels with the best samurai of that house, cutting off their topknots and thus stripping them of their honor, condemning them to commit seppuku. However, the Iyi clan dignitaries decide to cover up the whole affair and kill Hanshiro to save their house’s face. The bushido code is mercilessly trampled and discarded, forced to yield to self-interest and cruelty. Kobayashi shows this state of affairs in a highly expressive scene where Hanshiro, fighting his way to his death, destroys the Iyo ancestors’ armor, a symbol of tradition; the tradition of a true samurai family, which is forgotten, and its ideals are revealed as false.

Kobayashi is a stern observer of feudal Japan. His criticism can be devastating; he shows how the system destroyed not only individuals but entire classes, allowed abuses, and became a double-edged sword. Seppuku, a ritual as beautiful as it was cruel, became a tool of fear and terror. It begs the question: are other aspects of samurai culture also merely a memory from an adventure film?

The Way of the Warrior

The foundation of a samurai’s life was the bushido code (“the way of the warrior”), a set of principles drawn partly from Zen Buddhism, partly from Confucianism, and Shinto beliefs. The original purpose of the bushido code (it should be remembered that the proper code never existed in written form; it consisted of rules and laws derived from various sources) was to make warriors dependent on their feudal lords. But this set of moral and ethical principles became something more, growing into a symbol, contributing significantly to the image of the samurai as a romantic idealist constantly following the “way of the warrior” for self-improvement and the desire to help others.

However, as Aleksander Śpiewakowski, cited by Aneta Pierzchała in her book Japanese Film and European Culture, writes, the bushido code made an average samurai see his lord as everything, overshadowing the needs of the lower classes, which he simply ignored – and the Japanese warrior was far from extending a helping hand to a simple peasant. While Confucianism promotes the idea of caring for the weaker, it was not cultivated, Pierzchała continues. So, was the samurai characterized by selective moral principles? Not entirely.

In the film Ame Agaru (After the Rain) from 1999, by Takashi Koizumi, a longtime assistant of Akira Kurosawa, we watch the adventures of a ronin, a samurai who, due to his peculiar “unemployment,” is an undesirable element in a seemingly orderly feudal society. Ihei Misawa travels through Japan with his wife, helping the poor and perfecting his fencing skills through daily practice. Misawa, completely useless in a world without wars, unable to fulfill his destiny as a samurai, finds another truth in bushido, the way of the warrior. During his travels, the ronin helps encountered peasants, buys them food, engages them in conversation, often causing embarrassment with his manners and politeness. He arouses surprise – after all, he is a samurai, someone “better” than a simple peasant, yet he sits with him at the table as an equal. Of course, this is not a new attitude; already in earlier films by Kurosawa (often he, not Koizumi, is credited as the author of Ame Agaru, for which he wrote the screenplay but died during production) ronins, having no obligations to their often deceased lords, dedicated themselves to serving others. In the world cinema masterpiece, Seven Samurai, it is none other than seven ronins who agree to defend a village from bandits. In Yojimbo and Sanjuro, the last righteous samurai is Kuwabatake, the titular ronin. This does not mean, however, that Kurosawa created one-dimensional characters; quite the contrary.

Just as Sanjuro was characterized by calculation and a certain ruthlessness, not all samurai in the world depicted in Seven Samurai agreed to defend peasants for a bowl of rice. Even observing the characters of these seven heroes, we feel the class difference, the barrier existing between a peasant and a bushi (the memorable last scene where the young samurai Okamoto cannot stay with his beloved in the village because she is a peasant, and he must follow the way of the warrior). Despite this, the wall seems not to exist in After the Rain (Kurosawa also tried to break it down in Seven Samurai. Kikuchiyo, a peasant by birth, proves that one becomes a samurai by deeds, not by a certificate on paper), yet Misawa is not entirely “clean” in the light of the prevailing law. He is a ronin who fights for money. Here appears one of the most important motifs in Japanese art – the conflict between duty and feeling (respectively “giri” and “ninjo”). Misawa feels responsible for the peasants, whom, according to the Mahayana Buddhism and in the spirit of Confucianism, he is obliged to help.

On the other hand, the law is created by the sovereign, who is the highest value for a samurai. Does the status of a ronin, a warrior without a master, release Misawa from the duty of service? This question can be considered in many ways, but to our European consciousness, the behavior of the hero, who uses the money won in fights to help others, will be much closer.

However, in Japan, the bond with the sovereign, with the law he establishes, is stronger than anything else. Despite this, through his moral choices, Misawa remains faithful to bushido, like no other samurai shown in the film. Other bushi gathered at the princely court are corrupt, spoiled, fighting only for fun and to satisfy their vanity. As Pierzchała writes, the world lives by appearances – but for the ronin, there is no place in it.

Giri and ninjo

The aforementioned motif of the conflict between duty and feeling, giri versus ninjo, is a topos intriguing to anyone who has encountered samurai culture. The spirit of the warrior, torn by contradictions, could not show any hesitation; the bushi had to always remain unshaken and subordinate to his master, even if it was against his own moral sense and private interest. Perhaps the most outstanding example of the victory of giri over ninjo is the authentic story from the 18th century known as The Tale of the 47 Ronin, filmed and brought to literature dozens of times. In this episode from Japan’s rich history, we learn the value of giri for a samurai, the duty. After the death of their lord, deceitfully forced to commit seppuku, the most loyal samurai of the Asano clan swore revenge on one of the dignitaries responsible for the tragedy. For many years in hiding, often in poverty, disgrace, and oblivion, abandoning family life, they planned revenge on the man who led their lord to ruin. Can a better manifestation of loyalty to one’s master, whom the loyal retainers serve even after his death, be imagined? Moreover, after a successful assassination, they go to their death with joy, committing seppuku, as they fulfilled their destiny?

On the other hand, there are voices that these were lives wasted in the name of revenge, which we often despise; that these were wasted opportunities for the future, unnecessary sacrifices not only of the lives of the vendetta’s authors but also their families.

Another outstanding example, telling of the struggle between duty and feeling, is Masaki Kobayashi’s 1967 film Rebellion. In this story, we learn about the fate of the Sasahara family, whose head, proud samurai and master swordsman Isaburo, is forced to make an extremely difficult choice. He can either stand up for his son, from whom the prince wants to take his wife due to a series of events, or remain loyal to his superior. Sasahara chooses the former, thus sentencing himself and his family to death.

So, does ninjo win over giri? Yes and no. On the one hand, it seems that Sasahara is driven only by feeling, saying that in the name of his son and daughter-in-law’s blossoming love, he cannot accept the prince’s conditions; loyalty has its limits. However, if we look at his decision, Sasahara turns out to be faithful to the bushido code to the end. His rebellion is the only solution to preserve the family’s good name, a value equal to loyalty, as Pierzchała rightly notes. So, are we dealing not only with a conflict of heart and mind but also with duty versus duty? Not necessarily. Giri and ninjo in Rebellion seem to merge into one in Sasahara’s actions, although this is a somewhat risky and perhaps even paradoxical statement. Loyal to the samurai ethos, he does not accept injustice, does not agree to treat a person as a puppet to be manipulated. However, throughout his life, Sasahara remained loyal to his master and the laws he established. Kobayashi, in his film, shows that a samurai could also be a human, a multidimensional and thinking figure, but it was never easy, considering all the restrictions imposed on him. Sasahara’s friend, another excellent swordsman, Tatewaki Asano, remains faithful to giri. He acts against his comrade, even though it seems to go against himself. In Kobayashi’s world, there is no other alternative, as Pierzchała writes. In his world, one can be a conformist or die. There is no other way for a samurai, only in rebellion and death can they find freedom.

The Flower of Blooming Cherry

Despite even the greatest works of Japanese cinema not bringing us closer to historical truth as we would like, thanks to creators like Kobayashi or Kurosawa, one can learn more about the samurai ethos than from tons of books and studies.

Perhaps their vision is sometimes a show, a work of imagination, a false reality. However, Jakub Godzimirski, in his essay Death in Cinema, calls it a compromise aimed at conveying national culture to people from other cultural circles. Moreover, these creators fulfilled this goal excellently.

And what was the samurai like? It is best to use a metaphor. The life of a bushi was like the flower of a blooming cherry – fleeting, barely tangible, yet beautiful. Realizing their mortality, the samurai saw in death a world free from worries and appearances. Their attitude is best reflected in a masterful haiku poem by the poet Saikaku:

Borrowing a ray of the moon

For this journey

Of a thousand miles.

Words: Bartosz Czartoryski