HAIR Decoded: Stunning Depth of Deceptively Simple Musical

He had to grow up during an extremely difficult time for adults, let alone for innocent children. When he was 11 years old, his mother died in the Auschwitz concentration camp, and a year later, in Ettersberg (where the Buchenwald camp was located), his father also lost his life. Forman was left alone, surrounded by a small group of close relatives.

The text reveals important plot elements!

It seems there is no point in getting too sentimental, because in my Polish consciousness—strongly affected by the tragedy of the war—such stories are instilled from childhood. Perhaps it is precisely because the educational curriculum emphasizes them so strongly and does not allow us to forget that in a Polish mindset, the reaction is entirely different from what this great awareness campaign is intended to evoke. At some point, atrocities and tragedies turn into sad photos from school textbooks, and people stop thinking of this moral abstraction as an event that truly happened. We lose the strong emotional charge. Kids slam down wartime books. Another stupid reading assignment, a necessary break between Pratchett and Gaiman, King and Lovecraft, Saw and High School Musical. Hair

Polanski’s The Pianist is stupid because it’s too long. Critics point out the flaws because, after all, it’s the great Polanski. But the question is, is that what it’s all about? Can we not look at what happened decades ago from a perspective not tainted by academicism, historicism, or any other meaningless and categorizing “ism”? Just like Forman, that is, a kid who experienced it firsthand.

At this point, some readers might be asking themselves what I’m talking about since the headline of the page features a logo promoting a film about events that took place two decades later. And, to answer right away—yes, I intend to talk about Hair as interpreted by the Czech director. Hair, which—much like the hippie movement—grows, in my view, from the times when Szpilman had to abandon his piano and when Forman lost his parents. Times that today we grade on a scale from one to six (sadly).

Where is the connection?

Let’s note that the hippie movement—one of the main themes of the musical—emerged as a pacifist social group directed against the militaristic policies of the American state. The “soft blade” of the flower children’s weapon was aimed against what had caused devastation to the European continent two decades earlier and marked another pivotal moment in America’s short history, namely, the bombing of Pearl Harbor. In the consciousness of people growing up in the atmosphere of the Cold War and the arms race, during a time when American popular culture was developing vigorously, producing fantastic visions of a dehumanized world devastated by unimaginable tragedy, a movement arose that said “no” to repeating history. It’s clear that this “no” also reached the ears of soulless capitalists and conservative citizens who supported the war for the homeland—a strange concept, as if the homeland was so valuable that it was worth sacrificing thousands of young men for it. Isn’t the homeland sometimes like a sacrificial altar? A piece of stone where the blood of a few victims is spilled to restore balance in nature and gain a kinder glance from God?

Hippies recognized the vicious cycle their country entered when it became involved in the conflict in the Far East. Building their movement on the philosophy outlined since the 1950s by the avant-garde Beatnik group, they created a subculture (I use the term without the negative connotation it often carries) that contributed to the end of military actions in Vietnam. “Make love, not war” was one of the main slogans of the movement, and that is also a way to describe Hair, which we now turn to after a, let’s face it, overly long introduction.

Playing with clichés or stitching stereotypes together

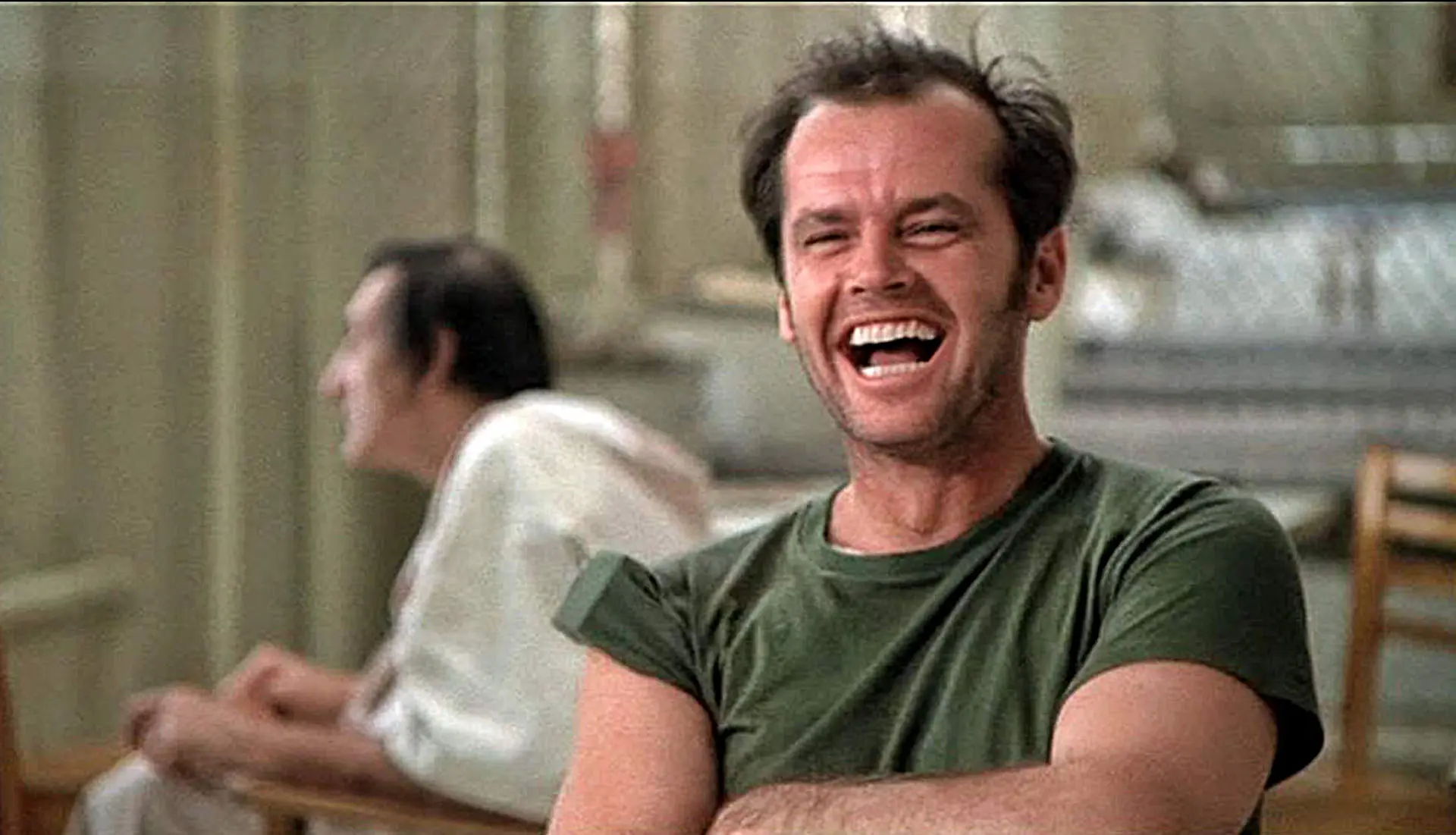

Forman perfectly understands the principles of the hippie movement, which—in my opinion—is especially close to him. It is no coincidence that a few years before the film adaptation of the Broadway hit, he took on the production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a film based on the novel by Ken Kesey (an author closely associated with the Beatnik movement mentioned earlier). And it’s no wonder because who—if not a man who lost both parents due to wartime actions—would relate more to the ideas of unrestricted freedom, love, and ending bloodshed in the name of pompous slogans that reek of conservative kitsch? Nevertheless, anyone expecting Hair to provide a deep and comprehensive look at one of the most significant subcultures in U.S. history will be sorely disappointed. Forman knew very well that delivering life truths in musical form wouldn’t work, so instead of a complete analysis of the social group, he chose to stitch together several banner stereotypes that have long been passed from one curious listener to another. In doing so, he avoided something that might be prematurely called “musical decorum,” because I don’t think anyone could imagine, for instance, Andrzej Wajda’s film character dancing in sync… It might be amusing, but also, undoubtedly, a bit silly. Kudos to Forman for sparing us that. Instead, we experience top-level synchronized dances and moral reflections that, in their simplicity, surpass many pretentious titles that try to explain the meaning of life to a bored audience in just a few minutes.

First and foremost, the characters are stereotypical—to the point of pain. To start with, there’s Claude—a boy who comes to New York from Oklahoma, a southern state in America that is conservative and therefore supports the government’s policies of the time. A little lost in the big city, shy and seemingly naive at first glance, he stumbles upon a group of hippies in a park who are carelessly prancing on the grass in search of loose change. He wants to fulfill his civic duty by fighting in the jungles of Vietnam, while they live in the moment and scoff at civic duties.

There’s a clash of two stances, people from two different worlds, a collision of two stereotypes. But soon enough, with intelligence and finesse, Forman shows Claude showing off in front of Sheila, a girl from the upper class and another stereotype on the payroll. Sheila belongs to an aristocratic family residing in New York. Banquets, dresses laden with frills, stockings, hairpins, and snobbery at the table. In the bedroom, when her parents aren’t looking—experiments with drugs. During her encounter with the band of hippies, there’s outrage that barely hides a smile and approval for people who aren’t afraid to do what they believe is right. People who have managed to cast aside what might be a well-tailored but utterly uncomfortable corset of conventions and commandments. In the hippie commune—Berger, Jeannie, Hud, and Woof. The first one plays the role of a leader (I realize I’m sinning by using this word in this context). He has an incredibly strong personality, comes across as crazy, and appears to have no inhibitions. Jeannie laughs a lot and is pregnant—she doesn’t know with which of her friends. What she does know is that each of the potential fathers is “beautiful,” and that’s enough for her. Hud, clearly inspired by Hendrix’s style, and Woof—a white boy with long, straight blond hair—are the next two clichés. Hippies straight out of photos from the times of Monterey or Woodstock.

So, we have a group consisting of a guy from the South (Claude), a rebellious individualist and instigator of most of the group’s activities (Berger), a girl from a good family suffocating in the corset of good manners (Sheila), and the remaining trio strictly following the most clichéd tenets of the hippie movement. It sounds fabulously kitschy, and the play with clichés doesn’t end with character portraits. The entire concept of the movement is presented as one big stereotype. Notice that in Forman’s depiction, hippies alternately—dance in sync, take LSD like it’s Holy Communion (an incredibly exaggerated scene), sleep, and bathe naked in ponds. Only occasionally do we see that the Czech director knows what he’s doing, that this entire story is just a formal game, leading up to the grand finale.

I have already mentioned one of the scenes — Claude’s performance in front of Sheila. A brief moment reveals to us the other face of a man who wants to serve his country. Beneath the mask of a conservative Southerner lies a young boy seeking fun and love. We could put it more bluntly — a kid stuffed with grand ideas that he will soon have to confront with his own worldview. The character seemingly gains another layer in the film’s finale when, with full awareness of the consequences, after his adventure with Berger’s gang and his encounter with Sheila, he nevertheless decides to serve in the military.

Of course, the question remains — would he have done the same if Berger hadn’t scared Sheila off with his childish joke during their dip in the pond? Furthermore, it’s worth noting the somewhat clichéd scene where Claude, determined to fly to Vietnam, sends a letter to his unfulfilled love (a letter that prompts his friends to visit and leads to the tragic mistake resulting in Berger’s death). So, we have this second layer and we don’t, because here (simply) Claude — the Southern boy, turns into Claude — the American hero writing letters to his beloved. Claude, we could say, changes his mask. Nevertheless, the galloping scene convinces me that Forman leaves both masks cracked. Somewhere beneath the created fissure, I still see a kid who doesn’t entirely understand what’s happening — this ultimately saves the character from being one-dimensional and trite.

The second scene is the argument between our hippie doppelgänger of Hendrix, Hud, and his wife, who unexpectedly appears on the street calling him by his (real) name. It turns out that beneath the guise of a liberated hippie, Hud hides a past he’s trying to escape. He’s married, has a child — he renounced all that. The confrontation with the woman drives him to fury; his friends no longer recognize him. Accompanied by the song sung by Hud’s wife, they try to convince him that he cannot abandon his family. The wife joins the commune to meet Claude, who is at a military training camp, but that moment (the reconciliation) is not the most important element of the scene.

The most important element emerges between the lines, comes from the lips of the sobbing wife, who, in her song, asks what sense there is in caring about social injustice and strangers if one can’t take care of the people closest to them. Open defiance against the traditional family model often led to disputes that severed parent-child relationships. Running away from home, abandoning the “old life” (like Hud), and many other behaviors that upset the established order. Isn’t that selfish? In a short song, the viewer is awakened from a colorful dream straight out of a psychedelic journey. Extreme individualism always leads to many small tragedies. Hippies were no exception — in the name of ideals, they sacrificed the ideals of others, the classic vicious circle. We always fall into it — the specter of freedom in a few minutes on-screen.

Of course, the scene that most contributes to shattering the colorful musical is the final one — the fatal mistake that places the entirely unprepared-for-military-service Berger on the plane departing for Vietnam, not Claude, who is visiting his friends at that time. After two hours of colorful images and ironic winks in the style of LSD communion, after wading through organized bands always ready for some synchronized antics to cheerful music, the viewer expects some grand finale in which at least a platoon of soldiers will join the dance, and helicopters from the sky will drop confetti instead of napalm. But that’s not what happens.

In a horribly brief moment — compared to the time spent on the song about the virtues of long hair — Forman shows us the plane taking off with Berger on board, a group of friends standing by his grave, and a peace protest outside the White House. The magic of the musical fades. It seems that Forman is saying to us — sure, you can portray hippies as a bunch of kids dancing to psychedelic rock in a haze of opium (I partly managed to do that). But don’t forget that every fairy tale and every musical comes to an end. Behind the colorful facade built by the media lies something more. In the case of Hair, what remains hidden are the ideological dilemmas of the hippie movement and the extremely pacifist undertone of the whole thing. The last few minutes reminded me more of The Wall by Pink Floyd than of Hair.

Berger and Randle Patrick McMurphy

These two characters are connected not only by Forman. Both, in a way, were the materialization of the hippie movement with its pros and cons. McMurphy in a more explicit way, as the film allowed for more explicitness — he didn’t have to spin pirouettes and sing about hair and fellatio. What I mean by the comparison is that both of them were extreme individualists searching for their place in the world. Both changed the lives of groups of people centered around them.

Berger was a sort of guidepost for his modest commune, McMurphy a man who brought a glimmer of hope to the bleak lives of the hospital inmates. The victim — in both Berger’s and McMurphy’s cases — was life itself. Moreover, the sacrifice of the most valuable thing in both cases was accidental, devoid of even a trace of heavy-handed heroism. I sincerely doubt that either of them would have selflessly sacrificed their life if they had been able to make a conscious choice. In this same aspect lies the tragedy of the entire hippie movement — a movement of extreme individualists fighting the world with spectacular rallies and pacifist slogans. The transformation of Beat philosophy, fascination with Eastern thought, bold opposition to a conservative society (again: Berger — dancing on the table in an upper-class residence, McMurphy — night escapades in the hospital) may have led to achieving their goals, but at what cost?

Hippies began experimenting with increasingly heavy psychedelics; the ideologues of the movement started to distance themselves from their children, who suddenly became dirty drug addicts desecrating the true ideals of the subculture. The movement died — just like Berger and McMurphy. However, all three left behind some hope for a better tomorrow. To quote Forman — the symbol of hope left by people like Berger, members of the hippie movement, are those few seconds of peaceful protest, while in McMurphy’s case, it is, of course, the image of a certain Native American breaking through a concrete wall with a sink ripped from the floor. The specter of freedom…

Conclusion

In conclusion, I must briefly return to the introduction and note that I did not intend to prove that Hair was some strange reminiscence of Forman’s war memories — no, no, and again, no. Hair is, for me, proof that despite the past being so firmly rooted in the realities of war and despite the hippie movement’s extreme opposition to what led to Forman’s and Szpilman’s tragedy, Forman can maintain his distance. He doesn’t resort to finger-wagging or preaching. He simply makes a musical full of song and dance.

This is, in my view, something extraordinary. Something we cannot even imagine in Poland, scarred by the specter of Auschwitz. Here, whenever we approach the subject of freedom, anti-war protests, and history, it has to be serious. You cannot dream like Forman in Hair. You cannot tell a fairy tale with a revealing moral. It’s not recommended; it would be given a failing grade. The Czech managed it. He played with stereotypes, flirted with Broadway kitsch, but he also left in us part of his beliefs, which emerge from that sea of kitsch when we least expect them. That’s the charm, for me, of the story about a bunch of hippies and a shy guy from the South.